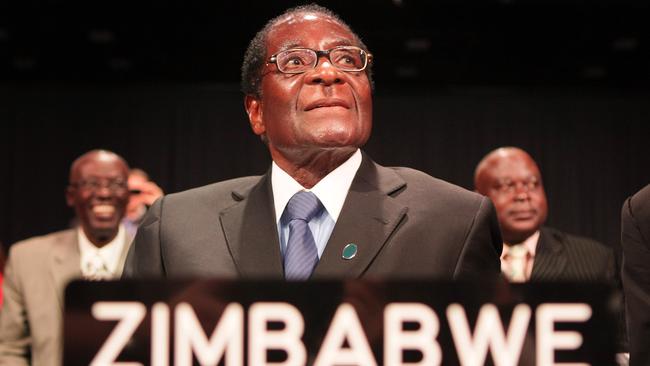

Former Zimbabwe strongman Robert Mugabe dead

The teacher who helped topple white colonial rule in Zimbabwe only to lead it to ruin, has died.

Robert Mugabe, a schoolteacher-turned-guerrilla fighter who helped topple white colonial rule in Zimbabwe only to lead the country to the brink of economic ruin, has died.

Mugabe died after years of declining health that saw him make frequent trips for medical treatment in Asia and less than two years after a bloodless coup ended his 37-year rule over the southern African country. He was 95 years old.

Cde Mugabe was an icon of liberation, a pan-Africanist who dedicated his life to the emancipation and empowerment of his people. His contribution to the history of our nation and continent will never be forgotten. May his soul rest in eternal peace (2/2)

— President of Zimbabwe (@edmnangagwa) September 6, 2019

Saviour Kasukuwere, a former minister under Mugabe and confidante of his family, said the former president died at a hospital in Singapore where he had been receiving medical treatment since April.

Mugabe’s topsy-turvy rule became the narrative of Zimbabwe’s independence story. In 1980, he was elected prime minister of the newly independent nation and initially went to great lengths to cultivate goodwill among white people. He would frequently invite Ian Smith, the erstwhile leader of the white-minority government that ran Rhodesia, to tea. The former colony had detached itself from the British Empire 15 years earlier, but many white settlers retained deep ties to Britain.

When his Zanu-PF party lost control of Parliament in 2000, in part because white farmers had swung their support behind a rival, Mugabe felt betrayed. In keeping with a pattern that would define his long political career, he moved to neutralize his opponents, giving the green light for veterans of Zimbabwe’s liberation war to invade white-owned farms.

Over the next several years, white farmers and business owners left the country, sending the economy into a tailspin. Thousands of Zimbabwe’s black professionals followed, many crossing the border to South Africa in search of work. Elections in 2002 and 2008 turned violent. Inflation spun out of control and the country began to import a main food staple—maize—to stave off hunger. As hunger and poverty spread, the man who came to power as a new African democrat ended up as another African despot.

It was an ailing Mugabe’s failure to control an intensifying succession battle that ended his reign. On the evening of Nov. 14, 2017, tanks and soldiers directed by Mnangagwa, whom Mugabe had purged as vice president days earlier, moved into the capital, Harare. Locked in his opulent “Blue Roof” mansion on the outskirts of the city, Mugabe watched his hold over the country and party evaporate within days.

Hundreds of thousands of Zimbabweans took to the streets to celebrate his impending departure. He resigned from the presidency on Nov. 21, 2017, as his Zanu-PF colleagues were preparing to impeach him.

Mugabe didn’t cease to chide his opponents, even in retirement. In one of his final public appearances, on the eve of 2018 elections that were eventually won by Mnangagwa, a frail and at times disoriented Mugabe endorsed the opposition over the party he had led for much of his life.

“I cannot vote for those who have tormented me,” he said, slouched behind a pile of microphones at his Harare mansion. “Pray that tomorrow brings us good news.”

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was born in Matibiri village on Feb. 21, 1924, the son of a carpenter father who later abandoned his young family, in a country that was then a British colony known as Southern Rhodesia. He was educated at Jesuit schools and studied at the University of Fort Hare in South Africa, where he was introduced to Marx and Gandhi—egalitarian thinkers who inspired his opposition to white minority rule.

The bookish Mugabe went on to become a schoolteacher in Ghana, where he met his first wife, Sally, also a teacher, who would turn—like her husband—to political activism. She died in 1992.

In 1960, Mugabe returned home to join a liberation movement that evolved in 1972 into a guerrilla war against white leadership. Rhodesian authorities arrested him in 1963, after linking his party, Zimbabwe African National Union, or ZANU, to the murder of a farmhand. Colonial authorities banned ZANU and locked up its leader.

Mugabe used the jail time to devour books on law and economics. In 1966, when his young son died, his jailers denied him permission to attend the funeral. Friends say Mugabe never forgave the Rhodesian government.

He emerged from 11 years of prison, writes Martin Meredith, author of “Mugabe: Power, Plunder and the Struggle for Zimbabwe’s Future,” even more committed to overturning white domination, his genteel manner disguising “a hardened and single-minded ambition.”

From his base in Mozambique, Mugabe commanded guerrilla fighters attacking white homesteads and planting land mines in Zimbabwe’s east. Rhodesian government troops lashed back and as many as 30,000 people died before independence in 1980. Elections then propelled Mugabe to power.

At first, he won over many of his critics—including Smith—with pledges of racial reconciliation. The British knighted Mugabe in 1994. He persuaded many white settlers to stay in a country where they remained a tiny minority—22 blacks to every white—but no longer exercised the levers of political power.

Yet in other ways, Mugabe remained a guerrilla fighter. In the 1980s, at a time when the world hailed him as a peacemaker, he allowed a North Korean-trained military brigade to kill thousands of people in the Western Matabeleland region, a stronghold of his old political partner and sometime-foe Joshua Nkomo.

Mugabe later expressed regret for the slaughter, describing it as a dark period, but he continued to cow opponents with a mix of violence and politics that doomed Zimbabwe’s economy, prompting a flight of skilled workers and private capital.

He supported forcible seizures of farmland belonging to whites, a violent and chaotic process that triggered Western sanctions and started Zimbabwe’s steep economic descent. The land often ended up in the hands of Mugabe’s political allies, rather than those of poor black farmers.

Long lines formed outside stores and shelves emptied. Between 2000 and 2008, Zimbabwe’s economy contracted by nearly half; by the end of 2008, inflation had peaked at 500 billion percent, according to the International Monetary Fund. Toward the end of what became known as the “Lost Decade,” the price of a loaf of bread soared to 80 trillion Zimbabwean dollars.

Western humanitarian aid and the adoption of the U.S. dollar helped avert a total collapse of the economy, but Mugabe became bitterly anti-West after the U.S. and the European Union imposed sanctions on him and his loyalists for human-rights abuses and undermining his country’s democracy.

Mugabe could be urbane and witty, but also calculating and coldblooded. Longtime opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai once described a dinner meeting that captured those paradoxical personal qualities.

“Can we eat?” Mugabe asked.

“No,” Tsvangirai replied. “I’ve already had something.”

“Come on,” Zimbabwe’s president implored, Tsvangirai recalled. “If you don’t eat with me, they will say it’s because Robert Mugabe kills people.”

Tsvangirai laughed, and sat down.

Throughout his presidency, Mugabe refused to groom a successor, frequently dismissing allies he feared were becoming too powerful. Yet his final spin on the carousel proved one too many.

In November 2017, Mugabe installed his second wife, Grace, a former typist nearly four decades his junior, as his vice president, ousting Mnangagwa, a longtime ally who had been nicknamed “The Crocodile” for his political ruthlessness. Dubbed “the First Shopper of Zimbabwe” and “dis-Grace” for embarking on extravagant retail expeditions to Asia, Mrs. Mugabe had a long list of enemies in the Zanu-PF party, who soon plotted to remove her from the line of succession.

From temporary exile in South Africa, Mnangagwa worked with the head of Zimbabwe’s armed forces, Constantino Chiwenga, to direct soldiers to take over Harare. Mugabe woke up in his “Blue Roof” mansion to find himself under house arrest, shut in by the security forces that had so long propped up his rule.

But the “Old Man,” as he had come to be known, clung on to power for nearly a week. In a televised address at which he was widely expected to formalize his exit, Mugabe, flanked by the generals who turned against him, insisted he was still commander in chief.

“You and I have work to do,” Mugabe said in a rambling speech two days before stepping down from the presidency. “Goodnight.”

He is survived by his second wife, Grace, and their three children Bona, Robert Jr. and Chatunga.

The Wall Street Journal