Prince Philip: Royal ‘larrikin’ devoted to Australia

Philip made more than a dozen visits to Australia, the last when he was 90, and forged links with scores of local organisations.

Opening the Melbourne Olympics in 1956 may have been Prince Philip’s most significant solo event in Australia – the importance of that sporting festival to an ambitious young nation could hardly be overstated – but his first visit had been years before, as an 18-year-old midshipman aboard the battleship Ramilles. It was 1940, only a year after he met Princess Elizabeth, who was then 13. Australia was at war, and the young sailor was back again in 1945, aboard the Royal Navy destroyer Whelp. So at the very least Philip’s relationship with Australia, as with so many of his other connections, was outstanding for its longevity.

His reappearance as a royal family member, with Elizabeth, had been planned for 1952, as part of a Commonwealth tour in which she to deputise for her ill father King George VI. However the young couple had only made it as far as Kenya, in early February, when the King succumbed to lung cancer; Elizabeth became Queen and Philip her consort.

The king’s death meant the couple’s immediate return to England and the trip was abandoned while the coronation took place. The palace regrouped and rescheduled, and as part of the blockbuster 1954 Commonwealth tour the pair spent 58 days in Australia during February and March, a jammed schedule that took in visits to 57 towns and cities.

It was during this marathon that an Australian camera crew gained a glimpse into a less formal side of the Royal couple’s relationship, according to a royal writer Robert Hardman in his 2012 book Our Queen. The crew was awaiting Elizabeth outside a house at O’Shannassy Reservoir in the Yarra Ranges, where she had agreed to be filmed looking at kangaroos and koalas, when Philip burst through the front door. Elizabeth was next, in hot pursuit, yelling at him to come back, then she grabbed him and they returned to the house. The Australians had captured the footage but exposed it on the orders of the royal press secretary. Elizabeth appeared soon after, apologised matter-of-factly and the shoot proceeded.

Two years later, Philip was back on a solo visit, to declare the games of the XVIth Olympiad open at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on November 22, 1956, in front of a crowd of 105,000, a polished performer of 35. With him on that trip, part of a four month international tour, was his private secretary and old navy friend, Australian Mike Parker.

Their close relationship and socialising had already given rise to speculation and the following year, with rumours of infidelity by Philip intensifying, Buckingham Palace issued a statement: “It is quite untrue that there is any rift between the Queen and the Duke.” Parker was less fortunate: when his wife Eileen accused him of adultery and began divorce proceedings, he felt compelled to resign. Ultimately Parker returned to Australia but Philip remained in touch with him until his death in 2001.

In the course of his long life Philip made more than a dozen visits to Australia, the last in 2011, when he was 90, and forged links with scores of local organisations who wanted him as their patron or honorary member. Most notable is his Duke of Edinburgh Awards scheme which has attracted 775,000 young participants since 1959.

In some ways he wore royalty lightly – according to one report from the late 1960s, he thought Australia should remain a constitutional monarchy only as long as that arrangement served a purpose – but he never put less than full effort into the relationship while it lasted, whether on visits here or encounters with Australians on home turf.

Often these meetings were with stars such as Barry Humphries and Kylie Minogue to whom he presented Britain-Australia Society awards in 2013 and 2016 respectively. He made the press when he complained about celebrity gardener Jamie Durie at the 2008 Chelsea Flower Show after Durie pointed out that what Philip had called a tree fern was in fact a Macrozamia Moorei. One of Durie’s assistants overheard him say: “I didn’t want a bloody lecture.”

In the same year, on meeting Cate Blanchett and hearing that she worked in film, he asked for help with his DVD player: “There’s a cord sticking out of the back of the machine. Might you tell me where it goes?”

Whether greeted with outrage or hilarity, as examples of a peculiar wit or gaffes, Philip’s utterances were memorable. During the 2000 tour on a whistlestop at a cotton farm in outback Bourke, NSW, he renamed the Piezometer, a device used to measure water depth in soil. “A Pissometer?” he queried the cotton farmer. He followed this with a comment on packaging of fruit. “Oh, you’re going in for this business of keeping people out of the food,” he said. “No way can you open the bloody thing.”

Two years later the couple was back, this time for the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Cairns hosted by the prime minister John Howard. Among the press corps, the view was that the most controversial aspect of the Royals’ visit would be their appearances with then Governor-General Archbishop Peter Hollingworth who was in a losing battle to hold on to the vice-regal top job, swamped by the scandal of his role in the failed handling of sex abuse allegations in the Anglican Church.

Instead, the royal tour headline belonged to Philip who while visiting the Tjapukai Aboriginal Cultural Park near Cairns, asked elder Ivan Brim: “Do you still throw spears at each other?”

The comment went round the world and sent royal minders into damage control. “It was a lighthearted remark and there are varying interpretations of what was said and, of course, no offence was intended,” a spokeswoman said.

A correspondent who covered the tour recalls: “It was like he was the embarrassing great-uncle” at the family gathering, the one who says the inappropriate things. However, accounts of Brim’s response vary. While according to one report he replied: “No, we don’t do that anymore”, in another he quipped in reply that they did. However when, in the lead up to Philip’s retirement, AAP went back to Brim’s son William, he confirmed no offence was taken. “I don’t mind – it was quite funny. I found it amusing, but I was rather surprised he said it. To me he was just a bit of a larrikin. Just observing him during the whole time down at the park, he seemed like a guy that would get on with anybody.”

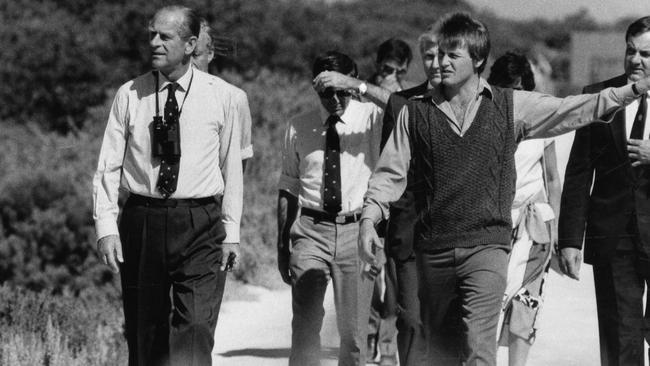

Looking back at the photographs of his Australian visits, what is striking is just how on-message Philip was, perhaps relentlessly so. His commitment to making those tours work is there in the countless shots of his tall slender form slightly stooped, head turned to hear the shy utterances of people awed to meet royalty, kind smiles to the school kids, and a beaming bonhomie at odds with his volatile reputation.

The last controversial headline for Philip in Australia came four years after his last visit, on Australia Day 2015, when then prime minister Tony Abbott conferred on him a knighthood for services to the British monarchy and the Commonwealth. Here, it was regarded as evidence of Abbott’s monarchism being hopelessly out of touch with the modern mood of his country.

Later, The Australian newspaper’s Foreign Editor Greg Sheridan would call the royal honour Abbott’s “worst mistake” in office and reveal the story behind it. Why the knighthood? Simply because Abbott had learned that the Queen wanted Philip to have one.

She presented the insignia to her consort at Windsor Castle in May 2015, attended by then High Commissioner Alexander Downer. The citation for Philip concluded: “He has served Australia with distinction.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout