Oil executives, bond investors urge Trump to make deal with Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro

Oil executives and bond investors are keen to show Donald Trump what they say are the perks of negotiating with Venezuela’s strongman instead of seeking regime change.

American oil executives and bond investors are urging President-elect Donald Trump to abandon his first-term policy of maximum pressure on Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro and instead strike a deal: more oil for fewer migrants.

The quiet lobbying effort comes as Mr Maduro hardens his authoritarian grip on the country with threats to arrest more opposition activists. They still challenge the July elections, in which Mr Maduro’s regime claimed victory without presenting evidence.

Some businessmen such as Harry Sargeant III, a billionaire GOP donor known for playing golf at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago club one day and jetting off to Caracas the next, are trying to show the incoming administration what they say are the perks of negotiating with Mr Maduro instead of seeking to dislodge him.

Last week, a shipment of Venezuelan asphalt sourced by Global Oil Terminals, part of a Florida conglomerate founded by Sargeant, landed at the Port of Palm Beach, just a few miles from Trump’s Florida residence. It was the first asphalt delivery from Venezuela to the port since Trump’s first administration imposed oil sanctions in early 2019.

The shipment, made possible by a license that the Treasury Department under President Biden gave some oil companies to restart operations in oil-rich Venezuela, highlights the pitch from advocates of a policy shift. They say making a deal with Mr Maduro would cut migration and help temper US energy prices.

An agreement would also help check adversaries such as China and Russia. Those countries gained ground in Venezuela following US economic sanctions which barred American companies from pumping and transporting Venezuelan crude.

The goal of restoring democracy in Venezuela, a cornerstone of Washington’s carrot-and-stick strategy in recent years, would be less of a priority for now, said people who are promoting what they call a more pragmatic approach.

“It is indisputable that the renewed flow of high-quality, low cost Venezuelan asphalt to the US has been a benefit to the American taxpayer,” Harry Sargeant IV, Global Oil Terminals president and the founder’s son, said regarding the cargo of 43,000 barrels of liquid asphalt, enough to pave some 88km of roadway.

“It has been a blow to our strategic competitors because under sanctions these barrels were turned into heavily discounted fuel oil that simply subsidised the Chinese economy,” he added.

Mr Maduro himself has floated a reset with Washington. “In his first government, things didn’t go well for us with President-elect Donald Trump,” he said in a recent televised address. “This is a new start, so let’s bet on a win-win.” Several American businessmen who travelled to Caracas earlier this year and met with Mr Maduro and his inner circle say the Venezuelans were convinced that Trump would win the US election and engage with Mr Maduro much like he had with the leaders of North Korea and Russia.

The Venezuelans believe that by facilitating oil supply to the US and accepting US deportation flights that had been suspended after negotiations with the Biden administration frayed, Mr Maduro could help fulfill Trump’s major policy objectives of deporting Venezuelan migrants, according to people familiar with the regime’s thinking.

Karoline Leavitt, spokeswoman for the Trump transition team said, “The American people re-elected President Trump because they trust him to lead our country and restore peace through strength around the world. When he returns to the White House, he will take the necessary action to do just that.” Venezuela presents one of the thorniest regional policy challenges for the incoming US government. Economic mismanagement, corruption and human-rights abuses under Mr Maduro triggered the exodus of nearly eight million migrants, some 700,000 of whom are now in the US.

Some economists and former diplomats say economic sanctions meant to financially choke off the regime not only failed to topple Mr Maduro but helped exacerbate the outflow of migrants by further devastating an economy that is largely dependent on oil exports.

“The challenge is how do you disentangle yourself and the US from a policy approach that utterly failed to generate political change in the country, impoverished more people and accelerated the migration of millions of Venezuelans,” said Thomas Shannon, a former high-ranking US diplomat in Latin America.

Polls show many more Venezuelans will leave if Mr Maduro stays in power. The strongman is set to inaugurate himself for a third, six-year term just 10 days before Trump moves back into the White House.

In recent days, the regime has ratcheted up threats to arrest María Corina Machado, the country’s main opposition leader. Machado went into hiding after she spearheaded a grassroots effort to manually collect and publish ballot sheets that the regime kept secret and showed Mr Maduro lost the July vote by a 2-to-1 margin.

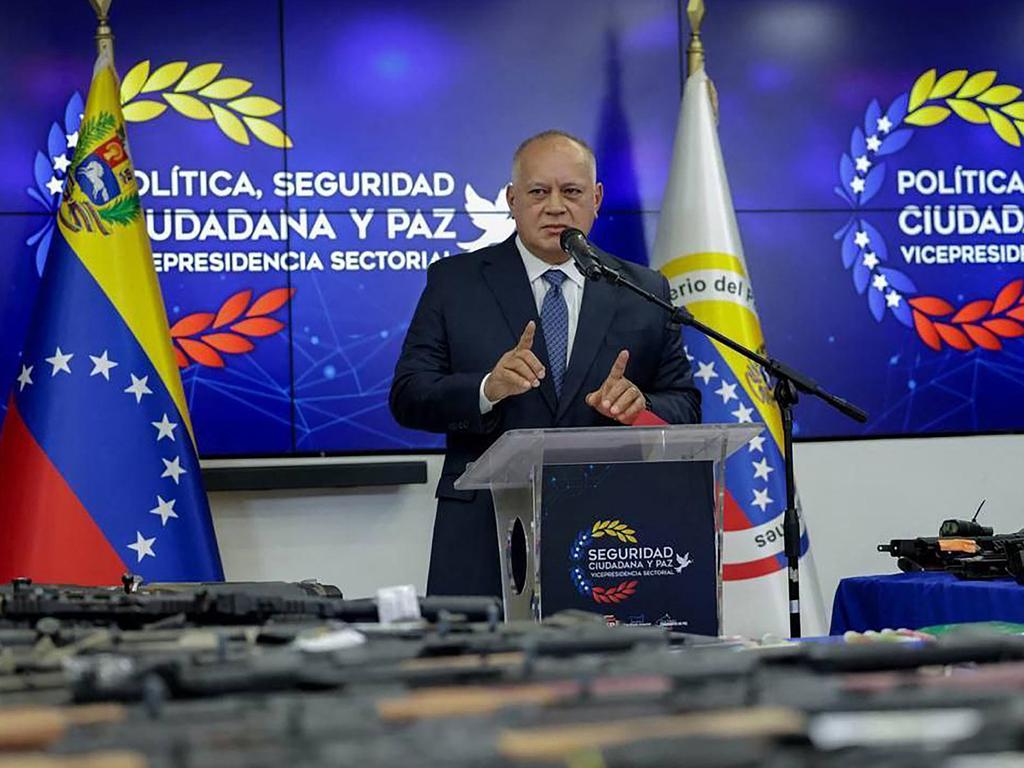

On Wednesday, the Biden administration added 21 Venezuelan security and cabinet-level officials to the US Treasury Department’s financial blacklist for abetting electoral fraud and repression. A total of 180 people in Mr Maduro’s inner circle have been sanctioned by Washington.

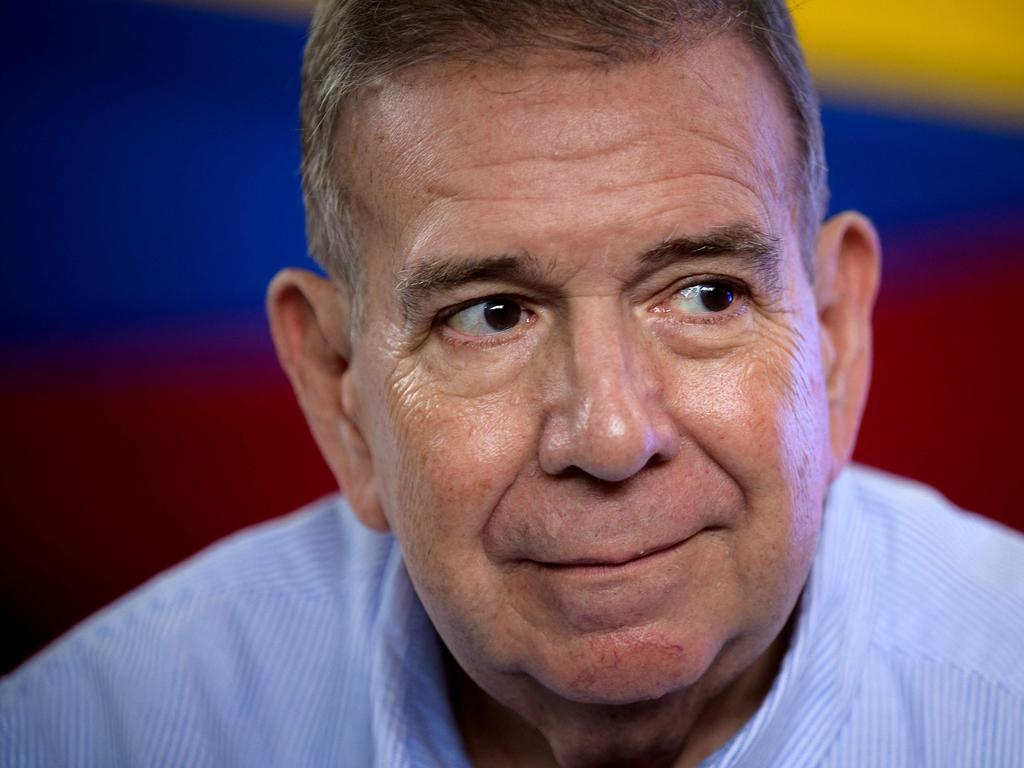

Mr Maduro’s rival candidate, Edmundo González, whom the US recognised as the rightful winner of the election, fled to Spain after facing threats of detention. González says he plans to return soon to claim the presidential seat, even though Mr Maduro continues to hold all the levers of power, from the courts to the military.

The opposition is calling for mass demonstrations on Dec. 1 as it urges the Trump administration to maintain its tough line against Mr Maduro.

In recent years, the Biden administration eased economic sanctions in a failed attempt to coax Mr Maduro into holding free and fair elections.

Ana Rosa Quintana, a former Republican congressional adviser on Western Hemisphere matters, said that Trump will give priority to taming migration and drug flows out of Venezuela, as well as freeing American prisoners held in the country while combating China and Iran’s influence in the region.

But a softer approach on Mr Maduro, she said, seemed unlikely. “It’s not going to be easy on him, that’s for sure,” she said. “I would not be concerned about the Trump administration falling into that kind of trap.” Scores of oil investors and Western bondholders sitting on billions of dollars’ worth of defaulted Venezuelan debt travelled to Caracas earlier this year to evaluate business prospects in the event of a bilateral breakthrough.

Eager to revitalise Venezuela’s once-thriving oil industry, Mr Maduro offered the possibility of sweetheart deals to investors who could help persuade the US to end sanctions, The Wall Street Journal previously reported. Some were treated to whiskey and steak at the Venezuelan capital’s exclusive country club and said they were impressed by a crime-free city and well-paved roads.

“I walked to meetings, took a ride-share. It felt totally normal, like they cleaned up the place,” said one American investor, recounting a recent visit.

On the campaign trail, Trump frequently alluded to Caracas, once a homicide hot spot, as being safe and had even quipped that he would move there if he lost the US election. Those comments had fuelled speculation among some investors that Trump would be open to an about-face on Venezuela.

But hopes for a policy shift took a blow when Trump nominated Florida Sen. Marco Rubio as his secretary of state. Rubio has long espoused tough international pressure against Mr Maduro and other authoritarian regimes in the Americas.

Other ardent Maduro foes also hold sway in the Trump transition team, including former national security adviser Mauricio Claver-Carone, as well as Elon Musk, who had supported the opposition and challenged Mr Maduro to a brawl amid the disputed Venezuelan election. Some prominent Republicans such as former defence contractor Erik Prince have been pushing the US government to increase the $15 million bounty it has on Mr Maduro for alleged narcoterrorism to $100 million. Mr Maduro has rejected US accusations as part of smear campaign to destabilise his government.

Earlier this month, the US House of Representatives passed a bipartisan bill banning Washington from contracting anyone with business dealings with Mr Maduro or any successor Venezuelan government that isn’t deemed legitimate by the US One of the bill’s sponsors is Florida Rep. Mike Waltz, Trump’s pick for national security adviser.

For now, the appointments cast doubt over the future of special licenses that the Biden administration granted to some oil companies to resume operations in Venezuela – including Chevron and Global Oil.

People familiar with the matter say there are more than 150 other requests for licenses that will fall onto team Trump’s plate once it takes office.

David Smolansky, a former Venezuelan politician lobbying for pressure against Mr Maduro from exile in Washington, warned that buddying up with Mr Maduro wouldn’t help ease migration flows.

“In the case of Venezuela, it’s a brutal dictatorship,” he said. “It doesn’t matter if you produce more oil. People are going to flee because of Mr Maduro.”

Dow Jones

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout