Obituary: Andree Dumon courageously bravely whisked fallen World War II flyers to safety

Andree Dumon would shepherd her charges through various checkpoints often explaining to Nazi guards that the men were relatives who were deaf mutes.

Europe was on fire in 1942. Nazi Germany had consumed much of the continent and was at the peak of its military-industrial power.

Adolf Hitler looked a winner. At first he must have thought his so-called Baedeker Blitz would smash British industry and Winston Churchill’s resolve. (Baedeker was the name of popular guide books for German travellers and enemy pilots used them to pinpoint English towns.)

But Churchill and his new ally, the US, returned serve in the fiercest year of aerial contest.

On the ground always were survivors of Allied aircraft that had failed mechanically or had been hit and whose pilots had ditched in darkness to uncertainty. But who knew so many of them would turn out to be deaf and mute?

Also on the ground were brave Dutch, French and Belgian resistance fighters, not only causing mischief with German trains and trucks but also networked into a web of supporters and trails by which the British, US, Australian and Canadian airmen would be whisked away, hopefully to neutral Spain or Sweden.

The flyers were fed, given civilian clothes and hidden until the dangerous passage could be organised. There was the Pat O’Leary Line, the Shelburne Escape Line and the Comet Line.

Andree Dumon and her older sister Micheline were part of the largest, the Comet Line. Between them they saved hundreds of flyers. Each spoke some English, a huge help because few of the flyers, other than some Canadians, spoke French.

Their family, led by father Eugene, a doctor who had worked in the Belgian colony of Congo in central Africa where his girls spent much of their childhood, was opposed to Belgium’s policy of neutrality.

Both women were petite and appeared much younger than they were. They dressed like teenagers and carried false papers identifying them as such.

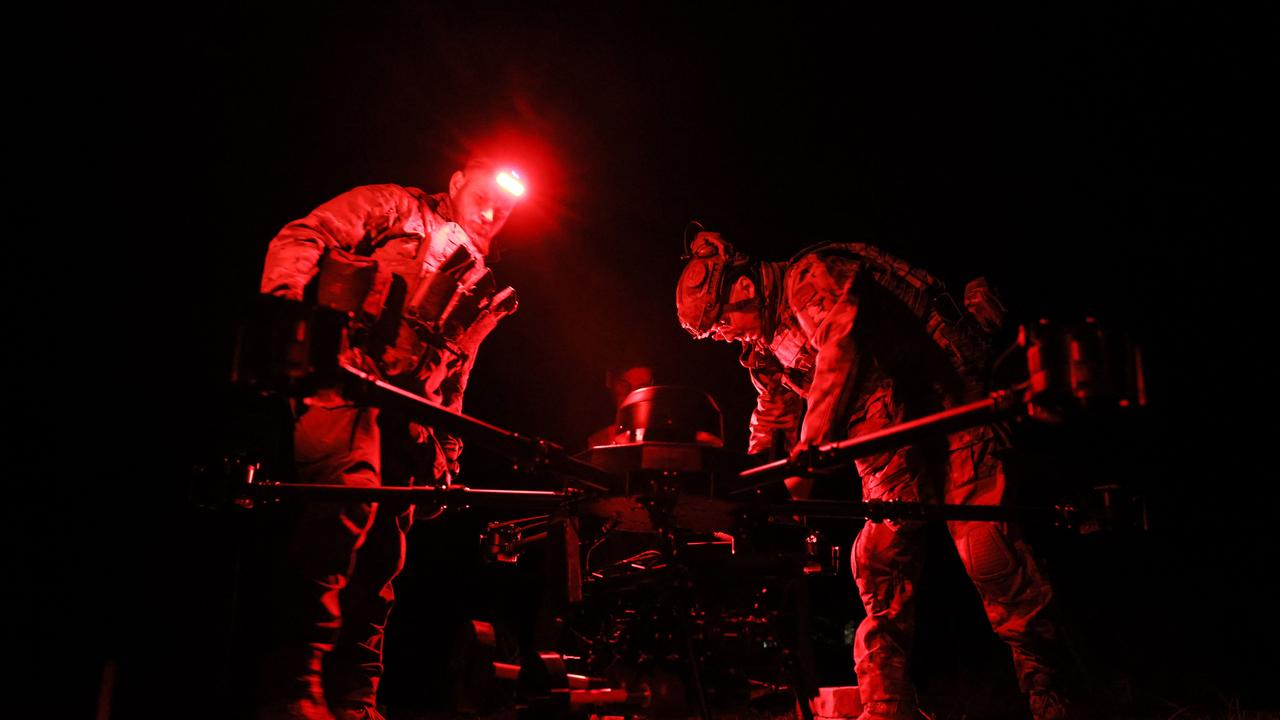

Having intercepted the men, they worked on a complex map of secret addresses and contacts to move them at night closer to one of the neutral countries – but these details were all in their heads; no one could afford to be caught with the Comet’s contacts written out. The Germans would have systematically killed them all.

Still, it was perilous work and the Comet Line had its pro-Nazi Belgian infiltrators. In August 1942, Andree – whose operational codename was Nadine – was betrayed to the Germans. She was arrested and severely beaten.

While preparations were being made to remove her from Belgium, she briefly saw her father also being arrested and spoke to him. She would never see him again. He died in a camp in the months before the fighting ended.

Andree passed through a series of camps before being sent to Mauthausen concentration camp, in Upper Austria, and to Ravensbruck, in northern German, where she was forced to work in such conditions that half the inmates died. Tens of thousands of others were murdered.

When she was liberated and returned to Belgium she had typhoid and was almost unrecognisable by her family. She took two years to recover.

Micheline uncovered a traitor herself and then made her way to England, by which time the escape routes had largely done their job.

More than 700 Comet couriers – a disproportionate number of them women – were uncovered and about 300 executed by the Germans. The rest were mostly tortured in an effort to unravel its people and systems.

Andree would shepherd her charges through various checkpoints, often explaining to the Nazi guards that the men were relatives who were deaf mutes.

One man she escorted to safety was the RAF’s Flt Lt Robert Horsley, whose plane had been hit several times as it returned from a bombing mission in May 1942. At 800ft, the captain told everyone to bail. Horsley parachuted into Bree in the far east of Belgium.

Andree found him and spirited him away to other couriers. Horsley returned to Britain from Spain and flew again, knocking out U-boats and bombing the docks at Bremen.

After the war he married and had a daughter, Erica, who was given the middle name Andree. The Horsley family migrated to Australia in 1972, where Horsley died in 2016. Erica stayed in contact with Andree and attended her 100th birthday celebration.

Andree was awarded a King’s Medal for “meritorious service in furtherance of the interests of the British Commonwealth in the allied cause”. Her sister was awarded a George Medal for “conspicuous gallantry”, and both received American medals for bravery.

After the war, Andree married and had two children. Micheline died in 2017, aged 96.

Andree Dumon. Resistance fighter. Born Brussels, September 5, 1922; died Nijvel, Belgium, January 30, aged 102.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout