Michelle Bachelet visits Xi Jinping’s flawed utopia of Xinjiang

For the first time in almost two decades, China has allowed the UN’s human rights chief into the country.

The UN envoy’s trip began with a special gift: a book of President Xi Jinping’s thoughts on human rights, delivered personally by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

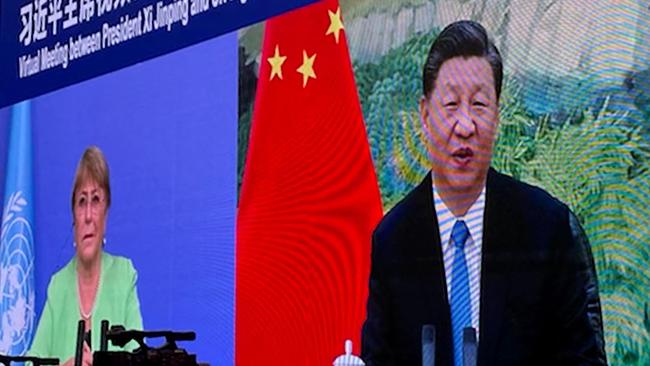

Days later, the UN’s Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet had an audience – albeit over video – with the book’s author.

“When it comes to human rights issues, there is no such thing as a flawless utopia. Countries do not need patronising lectures,” Mr Xi advised Ms Bachelet.

After years of stalling, China this week allowed the UN’s human rights chief into the country for the first time in almost two decades.

The six-day trip ends with a press conference on Saturday night. Only a few days will have been in Xinjiang, in China’s far west, where widespread evidence suggests more than a million Uighurs and other minorities have been “re-educated” in detention camps. China has said hardline assimilationist policies have been necessary to stop terrorism.

Ms Bachelet will release a long-delayed UN report on what has happened in Xinjiang after she leaves.

Every moment of her trip has been vetted. She and her UN team can meet only with people approved by China’s officials.

The tour has been conducted in a “closed loop”, nominally for Covid prevention. No foreign media have been allowed to accompany.

Despite the extreme limitations, Australian international law expert Philip Alston says it is “very important” the trip is taking place.

“I don’t think that the high commissioner would have benefited at all by refusing to visit on any other than ideal terms because they would never be available,” says Professor Alston, who teaches at New York University.

“(Bachelet’s) a pretty savvy character … She’s totally aware of all of the different political dimensions of what she’s undertaking.”

He has rare insight into what Ms Bachelet, a former president of Chile, is encountering.

In 2016, Professor Alston went to China as the UN Human Rights Council’s special rapporteur to prepare a report on extreme poverty and human rights.

Beijing’s heavy hand was everywhere, as noted in his subsequent UN report.

The surveillance was explicit. One lawyer he met was arrested after the visit. A “phone mechanic” was in the room of a colleague when she checked into their hotel, “repairing” a problem. “I’m sure that all of the phones in the location of (Ms Bachelet) and her party will have also been ‘repaired’,” he says.

Ms Bachelet will draw on a huge amount of research done on the situation in Xinjiang, as well as interviews outside China with experts and the Uighur diaspora.

Professor Alston says the trip itself been a catalyst for this.

Last year, more than 40 countries in the UN Human Rights Council, including Australia, called for Ms Bachelet to have “unfettered access” to Xinjiang.

Beijing made it clear that would never happen, insisting it would only allow a “friendly” trip.

“China hopes that this visit will help clarify misinformation and lay bare rumours and lies with facts and truth,” Mr Wang told the UN envoy on Monday.

New facts have likely been prepared for Ms Bachelet’s visit to Xinjiang, where she was scheduled to go to an organised trip to a detention camp.

Professor Alston says he was taken to a “Potemkin village” in Yunnan, a province in southwest China, with a large non-Han population. Also on his itinerary in 2016 was a centre for people with disabilities that he says resembled New York’s Trump Plaza Hotel.

“You get a pretty clear sense very quickly of what’s real and what’s not real. And I think that if that happens it redounds to the detriment of the government … It simply confirms advice that the monitor is getting that this is all phony-baloney.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout