Michel Siffre lived underground for months – a one-man test of time

Michel Siffre spent weeks underground, sometimes sleeping two hours, and at other times 18, without feeling the difference.

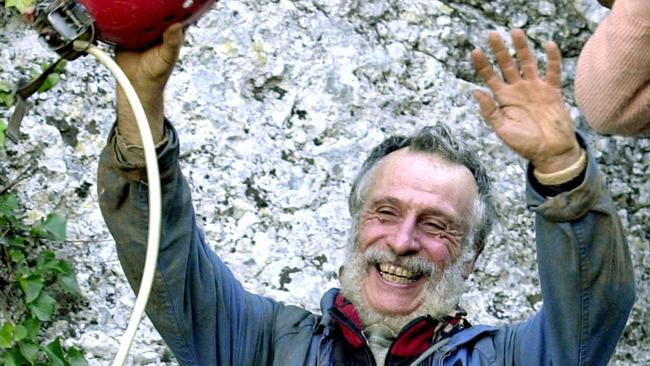

OBITUARY

Michel Siffre Speleologist

Born Nice, France, January 3, 1939; died Nice, August 25, aged 85.

When we get tired of life at the end of each wakeful day of about 16 hours we go to sleep for a seven or eight-hour shift, don’t we? Well most of us. It’s the natural pattern of things. But the idea of circadian rhythms that divide a week into seven even packages of consciousness and its dozy partner has faced challenges.

And not least of which by some of the smartest people: Napoleon Bonaparte would sleep four hours, then catnap through the day to come up with new ideas to dominate Europe; Thomas Edison slept about four hours and had a few naps during which he’d have light- bulb moments thinking up vacuum lights and the phonograph; Leonardo da Vinci slept just two hours a night with planned naps every four hours.

But these brilliant outliers were also out of kilter. In the end it took an eccentric caveman, Michel Siffre, to prove how humans really functioned when not governed by the decrees of timetables, Bundy clocks, daylight and never-ending presence of others. He was a scientist, educated in geology and speleology – the study of caves and their environments – at the esteemed Sorbonne in Paris.

His life changed direction in 1961, when Yuri Gagarin circled the Earth in a 2.3m ball of steel called Vostok 1, sparking the space race. Coincidentally, the French government was at the same time planning its first nuclear submarine. There was suddenly interest in how the human body would endure and react to living in confined spaces for long periods. The French submariners would journey to sea for 90-day stints (euphemistically called cruises).

That year, Siffre and some students had discovered a subterranean glacier in a chasm 130m below Mt Scarasson at the French end of the Ligurian Alps that march west from Italy.

The following year he decided to return – on his own, armed only with a torch a tent and food: “I decided to live like an animal, without a watch, in the dark, without knowing the time.”

He had read of an experiment with rats 40 years before that had shown the rodents have a permanent internal clock and wanted to discover if humans had one.

He had no references for time but, with a radio he contacted his small team up above (it could not contact him) at three points in his “day” – when he woke up, when he ate and when he was going to bed. He kept track of his body temperature, his pulse, studied the rocks and glacier and read books by lamplight.

During each “morning” call he conducted a simple psychological experiment in which he counted from one to 120 at the rate of a number a second. Unknown to him, he slowed down and towards the end the task was taking five minutes. He descended to the cave on July 16, with a plan to ascend to daylight on September 14. That day his team told him he had completed the 60 days; he estimated it was August 20. Time had lost track of him.

Over the next decade he conducted further underground experiments, sometimes with others, often funded by the French government. Then, in 1972, he descended into a cave in Texas for a six-month stay.

He had already established that our biological clock was off kilter with the celestial facts: each natural “day” was about 24 hours and 30 minutes. But he also discovered that in the dark our memories do not “capture the time” so well – they become slurred. It is hard to remember what you did “yesterday”. And during longer stays the biological clock days would stretch, finally settling at about 48 hours. He also recorded that the longer someone stayed in the dream sleep period, the more alert they were when they woke. The French invested into research to see if a drug could be made to stretch this period of sleep.

Siffre’s research was studied by NASA. Some astronauts made similar observations when their celestial days were upturned. A lifetime’s study evolved into the field called human chronobiology.

Aged 60 in 1999, and inspired by John Glenn’s return to space at the age of 77, he did a solo, two-month cave stay. He sometimes slept two hours, sometimes 18, without feeling the difference.

During one trip he supervised, a colleague slept for three days. Siffre thought he had better go down to make sure the fellow wasn’t dead. As he prepared to descend the man started snoring. All good then.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout