Joe Biden, Japan’s Fumio Kishida push for closer ties to counter China

Joe Biden and Fumio Kishida aim to improve military co-ordination amid worries about North Korea’s nuclear program, China’s efforts in Pacific.

President Biden huddled with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on Wednesday as the two leaders sought to strengthen their security ties in the Pacific as a counterweight to China.

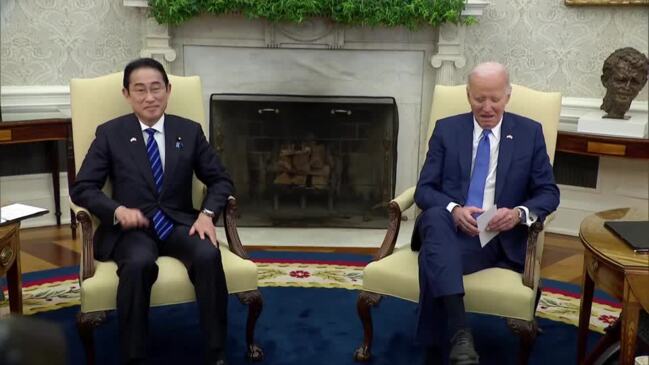

Biden welcomed Kishida to the White House as the two countries outlined plans to upgrade U.S.-Japanese military co-operation in the Pacific, amid concerns about North Korea’s nuclear program and China’s effort to extend its influence across the Pacific.

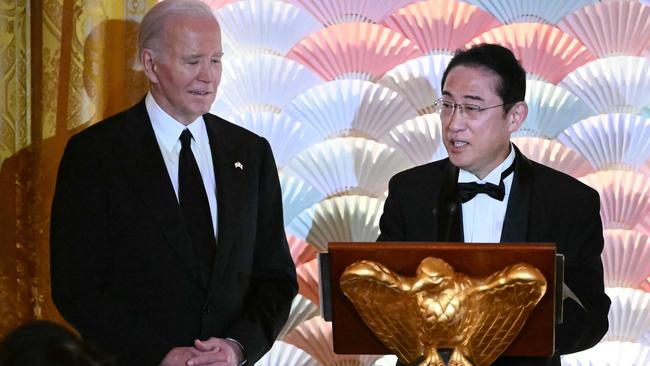

In a joint news conference, Biden said the two nations were “taking significant steps to strengthen defence security co-operation, are modernising command and control structures and we’re increasing the interoperability and planning of our militaries so they can work together in a seamless and effective way.” Meeting Kishida in the Oval Office earlier, Biden said they would discuss “how we can continue to enhance and ensure the Indo-Pacific remains a free, open and prosperous region in the world by standing together.” Kishida said the two leaders had “nurtured a friendship and a trust” and the nations were “at the forefront in maintaining and strengthening a free and open international order based on the rule of law.” Biden will end the day with a state dinner for Kishida – featuring a musical performance by Paul Simon – in a nod to their burgeoning partnership.

U.S. officials said ahead of the meeting that the U.S. and Japan would bolster their military ties – changing the military force structure the U.S. has in Japan and working more closely with a new joint Japanese command. The two countries will also look for ways in which they can co-produce weapons and tap in to Japan’s industrial strength.

The moves are designed to provide synergies between the two countries’ militaries in the case of a regional conflict. The most likely scenarios would be a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, the self-governing island that Beijing claims as part of its territory, or some kind of aggressive act by North Korea, which this year declared South Korea its No. 1 enemy and tightened ties with Russia.

However, any Japanese involvement is complicated by Japan’s constitution, which the government interprets as restricting the country’s ability to fight overseas except in rare and limited circumstances. Public opinion in Japan is cautious about the military’s involvement in regional conflicts.

Japan has been a stalwart ally of the U.S., joining with Western allies to impose tough sanctions on Russia after Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

The U.S. maintains about 54,000 troops in Japan from all the service branches. U.S. Forces Japan, led by a three-star general, handles some co-ordinating tasks. But its operational role is limited.

The service branches “report back to their component headquarters in Hawaii,” according to a February report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank. It called the structure poorly equipped to deal with regional threats in Asia.

Japan has ramped up military spending in recent years, a policy pushed by Kishida. The initial budget for the fiscal year that began April 1 calls for Yen7.95 trillion, equivalent to $52 billion, in military spending. That is up 47% from the initial budget two years ago, not including extra spending usually authorised later in the year.

By next March, Japan intends to set up a new permanent joint operational command for its military, known as the Self-Defense Forces. It will be headed by a four-star general with authority to direct all military branches and co-ordinate on an operational level with U.S. forces.

For now, any U.S.-Japan co-operation is likely to fall short of the arrangement in South Korea, where Washington and Seoul have agreed that a U.S. four-star general would be in command of combined U.S. and South Korean forces in the event of a war on the Korean Peninsula. Japanese officials said a Japanese commander would continue to hold independent authority over the nation’s troops.

The meeting comes as Biden faces re-election against former President Donald Trump, and as Kishida struggles with tepid popularity numbers, with the Japanese public concerned by falling real wages and a political-funds scandal involving some ruling-party leaders. A poll by public broadcaster NHK released Monday found support for Kishida’s cabinet was 23%, with 58% opposed.

Kishida’s three-year term as head of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party expires in September. Because the LDP head traditionally serves as prime minister, he needs to win re-election to the party post to stay in office. Despite his poor ratings, analysts say Kishida has a decent chance of hanging on, in part because several potential challengers were sidelined by the funds scandal.

“For President Biden, this is, of course, a chance to highlight and cement progress in the relationship, the most important bilateral alliance in the Indo-Pacific,” said Christopher Johnstone, a senior adviser and Japan chair with the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “For Kishida, it’s a chance to showcase his ties to the U.S., to prop up support at home.” Space exploration also figured into the discussions. The U.S. reached an agreement to make Japan a full partner in NASA’s Artemis moon program, including two Japanese astronauts in the mission and a moon rover developed by Toyota Motor. Officials said it would lead to a lunar landing by a Japanese astronaut, the first non-U. S. astronaut under the program.

Dow Jones

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout