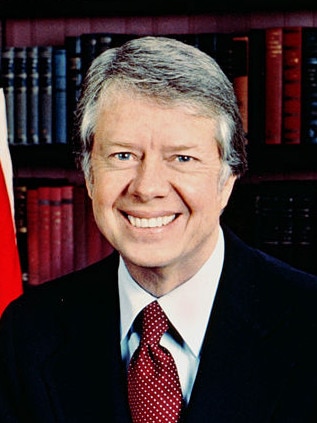

Jimmy Carter was in trouble – and then his embassy in Iran was stormed

Jimmy Carter’s presidency will be remembered for its bold plans to extract America’s kidnapped hostages from its embassy in Tehran, which ended in smoking ruins and sunk the president.

Jimmy Carter was lucky. As a dark-horse candidate at the 1976 US presidential election he came up against the unacclaimed, accidental incumbent Gerald Ford. Ford is the only president never to be elected to the US presidency or vice-presidency.

That Carter’s margin of victory over a Republican Party so damaged by Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal was thin did not augur well for the new leader. Carter managed just 50.1 per cent of the vote but he was little known outside Georgia, where he had been a state senator and governor.

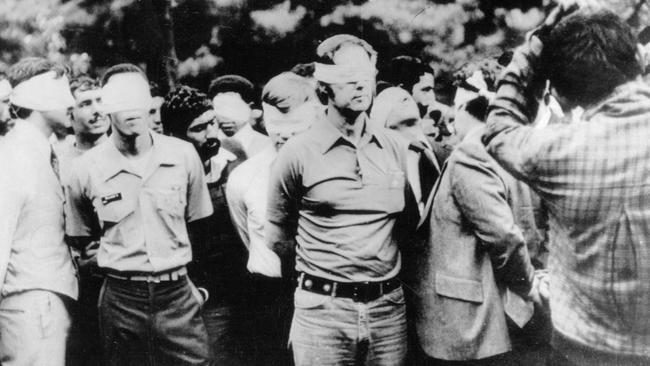

Carter was unlucky. His natural state was one of pessimism and across his single term he must have thought that justified: the economy slumped after the second round of oil-price shocks stemming from the collapse of Iranian oil production as shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi’s regime faltered and a global energy crisis ensued; Carter sought petrol rationing and described Americans as having a “crisis of confidence” with which they disagreed; he was in permanent conflict with congress, even its Democrat leaders; inflation took off, along with unemployment; he failed to win support for healthcare reform; there was a partial nuclear meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant; his drunk, rent-a-quote brother Billy Carter urinated in public; and revolutionary students stormed the US embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979, taking hostage 52 staff in an unprecedented attack on the global diplomatic system.

Carter’s presidency was doomed from that point. The diplomats would be held for 444 days until a new president was elected, not that Carter was in a position to do much more for them. Any military attack on Iran might well have been a death sentence for many of the kidnapped diplomats and, in any case, survivors would have been kept caged as terrorised bargaining chips.

Plans to extract the hostages – whom the kidnappers had been threatening to kill from day one – were under way 48 hours after the embassy raid and ended in spectacular scenes of chaos and failure.

Operation Delta Force had been formed two years before and this would be one of its first missions, but defence equipment and funding had been run down following the Vietnam war years and this would have a telling effect on what happened next.

In a complex series of manoeuvres scheduled for April 24, transport planes, helicopters and 106 Delta soldiers would land in the southern Iranian desert, refuel and head for a disused air base near Tehran before entering the city and evacuating the embassy staff.

The plans unravelled almost immediately: the hard sand they had tested during a bold forward mission weeks earlier had been replaced in storms by softer drifts; as the rescue mission was under way, a bus with 43 Iranian passengers unexpectedly turned up at the remote site and its driver and passengers were detained; a fuel smuggler in a tanker tried to drive at high speed through the growing throng – his truck was destroyed and passenger killed with rocket-propelled grenades (but the driver escaped); two helicopters suffered technical problems, one was abandoned in the desert while another picked up that team, the other returned to its aircraft carrier and a third helicopter encountered hydraulic systems failure.

They were now a helicopter short of the six it had been decided was the minimum needed to rescue the embassy staff. Team leaders used a satellite radio to contact their joint task commander in Washington to recommend calling off the mission. Unaccountably, it took 2½ hours for the president to respond. Operation Eagle Claw would be abandoned. But it wasn’t over.

With the choppers idling while waiting for the president’s decision they had been using up fuel and one was critically low and would need to be refuelled in another complicated operation.

During this, a helicopter kicked up clouds of sand, the pilot lost his bearings and it crashed into the refuelling plane on which five men were killed, another three in the helicopter.

The survivors were herded into the transport aircraft, the American helicopters, the bodies of their dead comrades and top secret mission documents abandoned.

The events were symbolic of the Carter presidency whose fate they sealed.

Carter was the eldest of four children of James Earl Carter Sr and Lillian Gordy. A gifted child, young Jimmy learned to read early. He played basketball and football at high school in Plains, Georgia, and studied for a science degree at the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, graduating 59th out of 820 in 1946. He studied nuclear physics and reactor technology at postgraduate level but did not complete a doctorate.

In 1946 he married Rosalynn Smith, whose family knew the Carters. They had three sons and a daughter – John William, James Earl III, Donnel Jeffrey and Amy Lynn.

Carter served on submarines in the Atlantic and Pacific. He was chosen to take part in the navy’s nuclear submarine program and qualified as a command officer. Carter enjoyed the navy but resigned to assume control of the family’s peanut farming business when his father died in 1953.

At home in Plains, Carter served on school and hospital boards. He was elected to the Georgia state senate in 1962.

In 1966, at the end of his second two-year term, he decided to run for governor of Georgia but lost, and returned to the farm to plan his next tilt. In the 1970 state gubernatorial campaign he promoted himself as a traditional southern conservative and won. In his inauguration speech in 1971 he said racial segregation – which his father reportedly supported – was a thing of the past and racial discrimination had no place in Georgia’s future.

Even Carter’s family was cynical when he announced he’d run for president in 1976 and he was given no chance in the primaries. But his outsider status slowly became a positive factor in a nation exhausted by Watergate.

His born-again Christianity helped and hindered. Playboy magazine asked him about the role of religion in his life.

He said: “I try not to commit a deliberate sin. I recognise that I’m going to do it anyhow, because I’m human and I’m tempted. And Christ set some almost impossible standards for us. Christ said, ‘I tell you that anyone who looks on a woman with lust has in his heart already committed adultery’. I’ve looked on a lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times. This is something that God recognises I will do – and I have done it – and God forgives me for it.”

As the confirmed Democrat candidate he was rating strongly, but Ford performed well in the first presidential debate since the famous encounter between John Kennedy and Nixon 16 years before. But Ford bore a unique burden; it is possible his cards had been marked in 1974 when the new president granted his former boss “a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offences against the United States” that many saw as corrupt.

On Carter’s first day in the Oval Office he pulled out the pardon pen too and absolved those who had avoided military service in Vietnam, up to 500,000 men. It was criticised, especially by veterans, but for Americans it brought a psychological end to the war.

Perhaps Carter’s greatest achievement were the Camp David Accords he negotiated with the bold leaders of Israel and Egypt, prime minister Menachem Begin, a lawyer-politician, and president Anwar Sadat, a revolutionary soldier. In a tentative step, both had visited each other’s country in 1977. The Middle East leaders had everything to lose – history shows it cost Sadat his life. And it didn’t start well. Begin and Sadat’s positions were fixed and their early statements were stilted confirmations of hard-set biases.

It is unthinkable today that any world leader could convince historic enemies to spend not three days as planned but a fortnight in a third country to untangle the endless complexities of their antique disputes. But Begin and Sadat clearly judged Carter to be different. He impressed them with his deep knowledge of the Bible, their geographies and the roots of their ancient frictions.

And it was Carter, in his own version of ping-pong diplomacy, who bounced from one room to the other seeking small concessions until he had built up a patchwork quilt of agreements that by September 1978 represented a deal that was a major punctuation mark in the history and future of the Middle East.

It was at all times a step from collapse. At one point Sadat left the room and ordered a helicopter to take him to the airport and home. Carter, employing his own brinkmanship by setting deadlines for decisions, made a heartfelt plea to him to stay one more day.

Eventually the parties hammered out a framework for peaceful solutions to their disagreements and autonomy for the West Bank and Gaza. A later agreement restored the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt’s control with Israel’s soldiers and civilians removed.

On the car on the way to address congress that day, Carter reminded his wife Rosalynn of Matthew’s biblical pledge: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.”

Executive Council of Australian Jewry co-chief executive Peter Wertheim said Carter was remembered with mixed feelings.

“On the one hand he deserves great credit for brokering the Camp David Accords, which led in the following year to a formal peace treaty,” he said. “(It was) the first between Israel and any of its Arab neighbours. It came after Israel and Egypt had fought five wars (that) cost of thousands of lives.” Wertheim said the close security co-operation between the two countries today would be unthinkable without Camp David.

But he said Carter later “surprised and disappointed” many with unfair criticisms of Israel, and appeared blind to generations of Palestinian leaders rejecting its right to exist.

A significant misstep for Carter was what became known as the “malaise” speech of 1979. He had delivered successive addresses to the nation highlighting the energy crisis in which the US found itself with pressure on oil prices being applied by OPEC and Tehran’s internal ructions, which were partly blamed on him pushing the shah too hard for reforms.

Home heating oil and petrol prices increased by more than 50 per cent (they wouldn’t reach the same level in real terms until 2008). Sensibly, the president asked Americans to lower the thermostat at home and to drive smaller cars, less often, and with more than just the driver in the vehicle. These ideas prefigured ride-sharing, more economical compact cars and other energy-saving economies. He had already installed 32 solar panels on the roof of the White House to heat water (which were theatrically removed by his successor as president, Ronald Reagan, although at least one survives at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington).

But Carter’s speech – initially well received – became a millstone. Two years earlier he had described the need to resolve the energy challenges as “the moral equivalent of war”. On July 15, 1979, he said: “The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.”

That came as news to many Americans. They appreciated the call to arms but did not share the loss of purpose. For good measure, Carter, sounding like the happy-clapper televangelist this family planning supporter certainly was not, said “all the legislation in the world can’t fix what’s wrong with America”. Ambitious senator Teddy Kennedy started calling colleagues that night with news he would challenge Carter for the right to be the Democratic presidential nominee the following year.

But neither could stop the upbeat Reagan’s inevitable sweep to power.

Former Labor senator Stephen Loosley, a strategic policy analyst and a commentator on US politics, said Carter’s presidency was a watershed in US politics. Nixon had successfully employed a “southern strategy” in the previous two American elections but the southerner Carter easily won the south in 1976.

“He won states like Kentucky, which we could not see in the Democratic camp these days. So in a sense it was an echo of what American politics had been,” Loosley said of an era that would close with Carter’s years and Reagan’s rise.

“Carter had a very real decency to him. And he handled himself in Georgia politics in a very liberal, very enlightened manner,” Loosley said, recalling that Georgia had produced “appalling” racist governors. Carter had long embraced the city of Atlanta’s slogan: “We’re too busy to hate.”

In what from the early weeks was condemned as a strategic mistake, Carter took his “Georgia mafia” to Washington rather then rely on road-tested administrators in the capital. “It was a very serious error,” said Loosley. “Subsequent presidents have learned to have a blending of trusted advisers from their home state, but they’ve avoided that good-old-boys syndrome – people who clearly were not able to master the byways of Washington. He never had an administration around him that understood Washington thoroughly or comprehensively.”

Tom Switzer, the executive director of the Centre for Independent Studies and a former senior associate at the US Studies Centre, said Carter distinguished his foreign policy from what many believed to be the “amoral realpolitik” of the Nixon-Ford era. During those years, their aggressive secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, famously announced: “I don’t see why we have to stand by and watch a country (Chile) go communist because of the irresponsibility of its own people.”

Switzer said: “(Carter’s) defenders said his human rights activism represented a welcome corrective to Kissingerian realism, with its hard-nosed focus on clearly defined national interests that are pursued with a cold calculation of commitments and resources.

“But Carter was also criticised for undermining the shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, by pushing him too hard to liberalise his regime.”

Switzer recalled that there was an intense White House debate about whether the US should allow the exiled shah into the country for medical treatment, but it was “agreed that the US had a moral obligation to accept the high-living but cancer-stricken leader”. Iran’s emboldened students stormed the US embassy in Tehran days later.

In the dying hours of Carter’s presidency – he’d lost the 1980 election, held on the first anniversary of the embassy attack – he was still negotiating to free up billions of assets and gold to be returned to Tehran and finally appeared to have sealed the deal for the hostages’ freedom. But Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, waited until moments after Reagan’s inauguration on January 20, 1981, before approving it.

Carter’s last public appearance was at Rosalynn’s funeral in November 2023. They were married for 77 years. His midwife mother brought young Jimmy into the hospital to see the neighbour’s new baby; Carter met his future wife hours after she was born.

He wanted to live long enough to vote for Democrat presidential candidate Kamala Harris. He did so on October 5, four days after turning 100.

Additional reporting: Graeme Leech

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout