Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei’s military counteroffensive

A series of memos reveals how founder Ren Zhengfei is preparing the telco giant for battle with Washington.

Huawei Technologies founder Ren Zhengfei was preparing to gather his top executives in Argentina in December 2018 to discuss a sweeping reorganisation of the Chinese technology giant when he learned his daughter had been detained during a stopover in Vancouver.

Meng Wanzhou, who also serves as the company’s chief financial officer, was wanted by the US for allegedly helping Huawei dodge sanctions on Iran. She urged her father to call off his trip.

“Dad, they are coming after you. Please be careful,” Ms Meng said, in a message relayed by her husband, a former Huawei employee.

Mr Ren ignored the advice. Accompanied by three close deputies, he took a circuitous route via Dubai and Brazil. Meeting at a resort in the foothills of the Andes mountains, executives devised a plan to decentralise the world’s largest maker of telecom equipment, starting with Argentina.

“It was risky, but if I acted scared, everyone else would too, right?” Mr Ren said in an interview. “I had to go anyway.” The Argentina summit placed Huawei on a more nimble footing just as the US was preparing to ratchet up a campaign to hem in the company Mr Ren founded 33 years ago. Huawei’s battle with the US thrust the once-reclusive 75-year-old entrepreneur, a former Chinese army engineer steeped in communist thinking, onto the global stage, a place he long shunned.

At stake is whether China or the US will control next-generation telecom networks — the sensitive and strategically significant building blocks upholding the internet and modern communication around the world. US officials warn Beijing could direct Huawei to sabotage or spy through 5G networks, which promise to provide superfast wireless speeds for coming technologies such as self-driving cars.

Huawei denies it would ever use its networks to spy, and Beijing says it has no rules compelling companies to do so.

Counterattack

Mr Ren has hunkered down in Huawei’s Shenzhen headquarters, drawing on skills acquired from a lifetime of battle.

With his focus turned to a US counterattack, Mr Ren assembled a council of close deputies and dispatched executives around the world to assuage worried customers. Lawsuits are a crucial part of the strategy, as laid out in memos viewed by The Wall Street Journal. A critical victory came this year, when the UK defied the Trump administration and cleared Huawei to build 5G networks.

But it is far from clear his counterattack will prevail. Over the past 18 months, the US has fired a fusillade against Huawei — from criminal indictments to a supplier blacklisting and restrictions on sales in the U.S.

The past month has seen new setbacks. In May, Washington restricted Huawei from obtaining chips it designed itself, threatening its plan to cut its reliance on the US. The move prompted British officials to consider steering telecom carriers away from Huawei gear, jeopardising its victory there.

Mr Ren’s daughter remains unable to leave Canada as she fights extradition to the US. Both she and Huawei deny wrongdoing. The case could drag on for years following a ruling in the US’s favour from the Vancouver judge last week.

Net profit growth slowed to its lowest in three years in 2019, as Huawei’s overseas business was squeezed and it became more reliant on customers back home. Huawei has been shut out of 5G markets including New Zealand and Australia.

Cut off from Google’s popular apps, the company’s smartphone brand is losing ground overseas, threatening its once-booming consumer business, which represents more than half its revenue.

This account of Mr Ren’s marshaling of Huawei’s fight with the US is based on dozens of interviews with current and former Huawei employees, associates of Mr. Ren, internal Huawei documents and interviews with Mr Ren in November and March.

In Argentina, the days of meetings ended with a restructuring plan that handed more authority to regional bosses running Huawei’s sprawling field operations, spanning more than 170 countries. The new plan involves thinning the management ranks at headquarters and giving local managers more autonomy by, for instance, allowing them to end contracts independently, according to a copy of the plan reviewed by the Journal.

The entire initiative will take five years to complete, Mr Ren said, adding that it was inspired by nimble-minded US military management philosophies.

“People assigned to the Pentagon may not necessarily have a bright future, while people working in the field may get promoted faster,” he said, explaining the importance he assigns to the company’s frontline workforce. “It’s going to be the same at Huawei.”

In the months that followed, Huawei became a more forceful presence around the world, promoting its viewpoints with a string of public events and more aggressively responding to the West.

At home, Mr Ren delivered rally-the-troops speeches to motivate staff, evoking his military past and issuing dire warnings about Huawei’s survival.

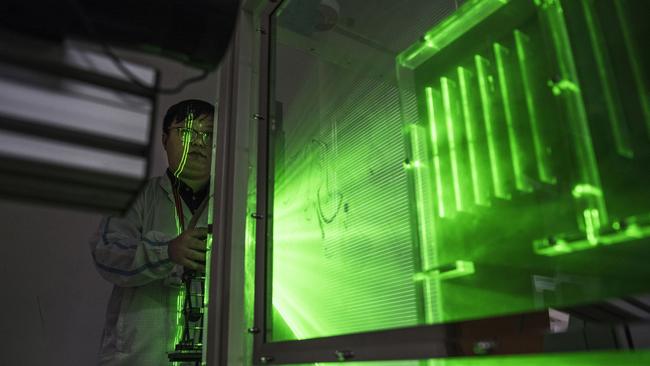

Just over a month after his daughter’s arrest, Mr Ren visited a Huawei research-and-development centre in Hangzhou, commanding employees to learn from US tech giant Google and “surge forward, killing as you go, to blaze us a trail of blood”, according to a transcript confirmed by two Huawei executives.

In February, at a Huawei campus in Wuhan, Mr Ren told assembled employees “the company has entered a state of war”, according to a transcript.

Mr Ren still speaks with reverence for the US, even as he oversees the fight with Washington. He remains an admirer of American culture, and often offers praise of President Donald Trump, sometimes with tongue seemingly in cheek: He said a gilded hall on Huawei’s new campus in Dongguan, near Shenzhen, had been nicknamed “Trump Corridor”. Cross-country travels through the US in the 1990s brought the budding executive to Silicon Valley, where he took copious notes about his meetings with executives there.

“I have been to the United States of America many times and each time I visit I’m deeply impressed by the bold, innovative spirit of the American people,” Mr Ren wrote in a 1998 essay titled, “What Can We Learn From the American People?”. “Through the positive impact of the different cultures of immigrants over many generations, a culture of innovation thrives in the US,” he wrote.

Humble beginnings

China’s southwestern province of Guizhou, where Mr Ren was born in 1944, is draped in lush hills, dotted with scenic villages. Duyun, where Mr Ren went to middle school, is bisected by modern highways. The region is a popular vacation destination for Chinese travellers and a data-storage hub.

When Mr Ren was born, however, Guizhou was a backwater. The son of two school teachers, Mr Ren and his six siblings survived the famine under Chairman Mao’s catastrophic “Great Leap Forward”, and Mr Ren has spoken frequently of how he was toughened by poverty.

After graduating from college with an engineering degree, Mr Ren eventually joined the army as an engineer. In his early 30s, he made headlines in state media for an invention at a factory.

His work won him recognition in Beijing and eventually a seat at the Communist Party’s National Congress in 1982.

Discharged from the army in a massive decommissioning wave, Mr. Ren co-founded Huawei in 1987 in a Shenzhen apartment as an importer of telecom switches — devices that connect phone calls — from Hong Kong.

The company began manufacturing and sold products across China’s countryside, then its cities.

Huawei says the Chinese government has never owned a stake, though a Journal analysis found that the company benefited from tens of billions of dollars worth of state financial assistance over the years. Huawei says it never received special treatment from the state.

As Huawei moved beyond domestic telecom deals, it opened its first overseas field office in Russia and later expanded into Western Europe. Its annual revenue doubled for years during the early 1990s. Huawei’s attempts to enter the US in the early 2000s attracted the attention of officials in Washington. In 2011, one of Mr Ren’s deputies, Ken Hu, wrote an open letter inviting a US investigation of Huawei to clear long-held concerns by US officials that using Huawei telecom gear exposed networks to Chinese-government espionage. The House Intelligence Committee took Huawei up on the offer — and the next year published a 52-page report warning that Huawei and its main Chinese rival couldn’t be trusted to be free of Beijing’s influence. The company has been largely locked out of the US ever since.

Over the next several years, Huawei rose to dominate the telecom-equipment business despite the US stance, and Washington’s position against the company hardened. By 2019, Mr Ren became focused on countering the mounting US attack.

He enlisted an inner circle of Huawei board members to co-ordinate strategy. They include Catherine Chen, Huawei’s head of public affairs; Song Liuping, the chief legal officer; and Liang Hua, a longtime Huawei executive who holds the title of board chairman, and who runs the company’s finances in Ms Meng’s absence.

Ms Chen, in a 14-page memo in October 2019, laid out the strategy communicated by Mr Ren. The memo, whose contents haven’t been disclosed previously, outlined a three-pronged plan for fighting back: engage foreign media, battle on the legal front and invest in technology.

According to Ms Chen’s memo, Mr Ren had described the company’s public engagement strategy as a “Marshmallow Campaign”. Huawei sought to turn around public suspicions of the company with a media charm offensive, led by Mr Ren, who had barely given interviews to foreign media or spoken on the global stage.

“Not pushing too hard, but still making our messages stick,” was Ms Chen’s description of the strategy. She added: “Mr Ren has pointed out the right way forward for us, which is to adopt a Western mindset to solve the issues we face in Western markets.”

Mr Ren gave dozens of interviews, often laughing and embracing the spotlight in a way that surprised associates.

A later memo quoted Mr Ren describing the company’s win in convincing the UK to let it build 5G networks as “just like the success of the Battle of Stalingrad, which was a turning point that reshaped the global landscape”.

Courtroom battles

Huawei’s counteroffensive entered a new phase in March 2019.

Mr Ren had long cautioned that Huawei should bide its time with the US, but he grew tired of having US officials be the only voice in the room. The company decided to file a lawsuit challenging a defence Act that blocked federal agencies and contractors from buying Huawei products.

To announce the lawsuit, Huawei arranged a press conference in Shenzhen. Scowling executives in suits argued before hundreds of journalists that the law’s provisions amounted to a “bill of attainder”, an unconstitutional action convicting an entity of a crime via legislation.

Unstated at the press conference was that members of the company’s Washington DC staff had opposed the lawsuit. In an email to Ms Chen before it was filed, they called its timing “a major mistake” that would mark a setback in efforts to engage with US officials. “To have a lawsuit against the law is likely to chill, or eliminate entirely, any willingness of the US government agencies to engage with Huawei,” the US executives wrote.

Mr Ren said there was no internal dissent over the decision to sue. He said the lawsuit was a necessary countermeasure to the US’s relentless assault on Huawei. The company filed a second lawsuit in the US on December 5, this time accusing the Federal Communications Commission of violating its due-process rights for a decision banning rural customers from using a subsidy to buy Huawei gear. A Texas judge threw out the first lawsuit; the second is pending before an appeals court in New Orleans.

“The fact is, we were forced to speak up and stand up and defend our position,” Mr Ren said in an interview. “The US is waving a stick at us, and after taking a blow from the left, we can’t just wait for the next one to come at us from the right.” Mr Ren believes that his more-aggressive approach has been successful — and by some counts he is right. Huawei continues to rack up new contracts to build 5G networks, which number more than 90. Even as the UK wavers, other European countries such as Germany have signalled they plan to go with Huawei — and Chinese diplomats have threatened to cut imports from some countries that ban the company.

“The US is a powerful country and has a powerful government, so people generally trust what they say,” Mr Ren said.

“As time goes by, though, more and more facts are coming to light, and the sky is changing from pitch black to a dark grey, to a more neutral grey — and hopefully soon to a light grey.”

Huawei last year bought large amounts of American technology despite its blacklisting — some from suppliers who secured licences from Commerce Department officials, like Microsoft, and others via a technicality exempting American components built offshore — and is ordering a massive increase in R&D spending to fill in gaps in its supply chain.

Still, new fires keep emerging. In February, prosecutors expanded an existing indictment of Huawei to include allegations of technology theft and racketeering — a charge traditionally used to prosecute organised-crime figures. Trump administration officials revealed plans to limit Huawei’s access to the Taiwan-based builder of its chips, threatening its ability to obtain advanced chips and opening the door to rivals such as Sweden’s Ericsson AB.

Last week, Canada’s biggest telecom carrier said it was turning to Ericsson to supply 5G equipment in a deal that would reduce its dependence on Huawei.

In 2013, Mr Ren told executives at a telecom operator and customer in New Zealand that he would like to retire in the Pacific island country and own a cafe. Now, the idea of retirement seems far off — he told an interviewer last year that he has delayed it to focus on the crisis at Huawei.

Yet Mr Ren has reasons to be optimistic. The explosion in remote working is increasing demand for the company’s networking services. Demand for Huawei laptops, tablets and other gadgets is booming, he said. Huawei has donated medical supplies to hard-hit areas — earning an unusual tweet in gratitude from New York Governor Andrew Cuomo.

Once the pandemic ends, Mr Ren says, “we’re actually concerned that we may not be able to produce enough [telecom] equipment to meet these needs.” Though he won’t commit to a successor, Mr Ren has drastically scaled back his public appearances this year.

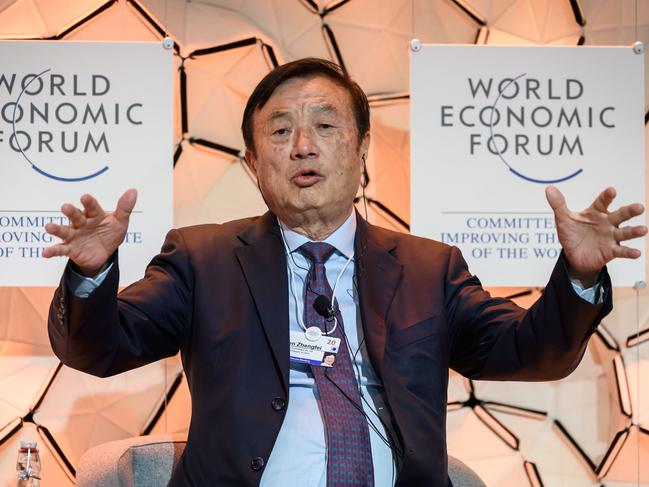

The pandemic has made it impossible to receive customers and other outside visitors, and Mr Ren has had few face-to-face meetings. Following a brief talk alongside historian Yuval Noah Harari at the World Economic Forum at Davos in January, Mr Ren has remained in Shenzhen, giving pep talks to frontline staff via video-conferencing software. He recently encouraged staff to promote a video of members of the Shanghai Ballet practising Swan Lake while wearing surgical masks, according to a person familiar with the matter.

On Twitter, Huawei’s official account touts the dancers’ “spirit of survival”. “While our company is climbing upwards, I will be on the way down due to my physical condition, and will not be able to continue climbing with the company,” he said. “We now know where our pain points are and where we should improve.”

Additional reporting: Jacquie McNish

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout