How Australia helped forge a king

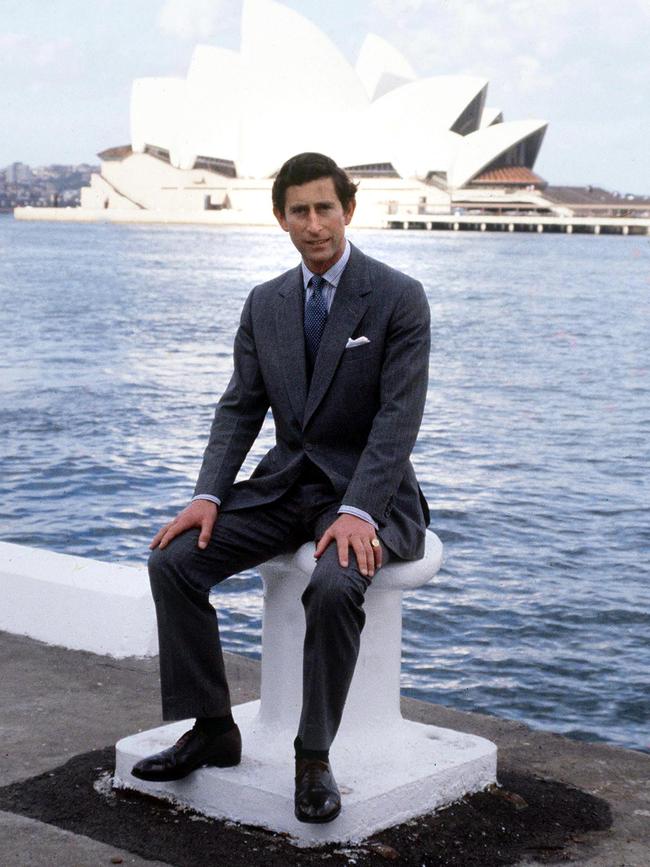

Australia has a special place in the King’s heart, for it was here he first found his voice and his confidence.

No British sovereign has known this country like he does. Charles sat in the red dirt with the First Australians, plunged bare-chested into the surf like a carefree local. We helped mould the man and groom a king.

He has been coming here since he was a schoolboy dispatched to the rustic Timbertop campus of Geelong Grammar to broaden his horizons.

Charles returned no fewer than 16 times on official visits, the most clocked up by any member of the royal family. Now that he has realised his destiny, Australia is certain to be among the first stops when he tours his overseas “realms” as the newly crowned King.

“But will I be welcome?” he asked Australian diplomats recently. Charles is all too aware that he can’t command the affection and respect his late mother did, with opinion polls in Britain showing mixed support for the monarchy on his watch.

While a survey published last week by the conservative-leaning Daily Mail found a majority of Brits would vote to keep the House of Windsor in its privileged place, those aged between 18 and 34 favoured a republic.

A late April poll by the National Centre for Social Research revealed backing for the monarchy had slipped to a historic low – 45 per cent said it should either be abolished, was not at all important or not very important.

Charles would be aware that the slumbering issue of an Australian republic is showing signs of stirring under Anthony Albanese. The Labor government has an Assistant Minister for the Republic in Matt Thistlethwaite and could develop an appetite for further constitutional reform if the referendum for an Indigenous voice succeeds later this year.

All eyes will be on the reception he receives when he visits, presumably with Camilla by his side. It would be her fourth time in Australia but not since those dark days following the death of Princess Diana in 1997 is the public’s reaction likely to be so carefully tracked.

Last Thursday’s YouGov poll in this newspaper suggests Australians are still warming to the new Queen, whose approval rating, at 35 per cent, lags even problematic Prince Harry’s. Charles’s numbers are up nine points since 2021 to 52 per cent.

The couple was last in Australia in 2018 when Charles deputised for the queen to open the Gold Coast Commonwealth Games. He then struck out on his own to tour Queensland, giving free rein to a propensity to speak his mind on environmental issues.

Charles waded into hot water on the Great Barrier Reef, venturing in a roundtable discussion on its future on Lady Elliot Island that he had been surprised to learn mainland farmers were using chemicals banned for 25 years.

This turned out to be a bigger surprise to the farmers concerned, who complained that the then heir to the throne must have been misinformed. “I fear he is getting outdated information,” said Paul Schembri of Canegrowers Australia.

Would Charles as the visiting King court such controversy? Would he even appear in a setting where his past activism could be revisited? You can bet his forthcoming itinerary in Australia will be compared to where he went and who he met previously; it promises to be an important pointer when the actions of the sovereign, constrained though they might be, sometimes express more than can be said.

Charles will turn 75 in November, an age at which his parents were slowing down. In their swan-song tour in 2011, the late queen and Philip based themselves at Government House in Canberra and spent six of 11 days in the national capital, not venturing beyond Brisbane, Melbourne and Perth on the way home for a Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.

Yes, the then 85-year-old Elizabeth had more than a decade on her eldest son today, but Charles’s capacity and willingness to tour, especially with a wife who has a well-canvassed aversion to flying, will be critical to his standing in the largest of his far-flung realms, especially if the republic debate takes off.

Since the 1999 referendum defeat, the hope of the republican side was that his accession would reignite the flame. Perhaps it’s wishful thinking when Australians, in the main, have evidently retained a soft spot for the awkward teenager who arrived at Timbertop in 1966 and liked it so much that he stayed on for a second term.

“I’d never really gone away from home until I came here,” Charles once told The Australian’s editor-at-large, Paul Kelly.

“What it did was help me to know more about myself and also how to talk to people.

“I literally had to sink or swim out here, and in the end I began to swim.”

Of course, the cynic might argue that he would say that, having endured five long years at Philip’s alma mater, the Spartan Gordonstoun school in the Scottish Highlands. Charles is said to have dubbed it “Colditz in kilts”, though he is also on record disputing the “amount of rot talked about Gordonstoun and the careless use of ancient cliches used to describe it”.

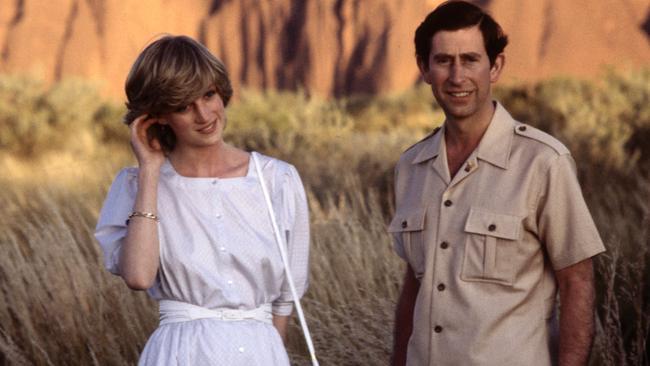

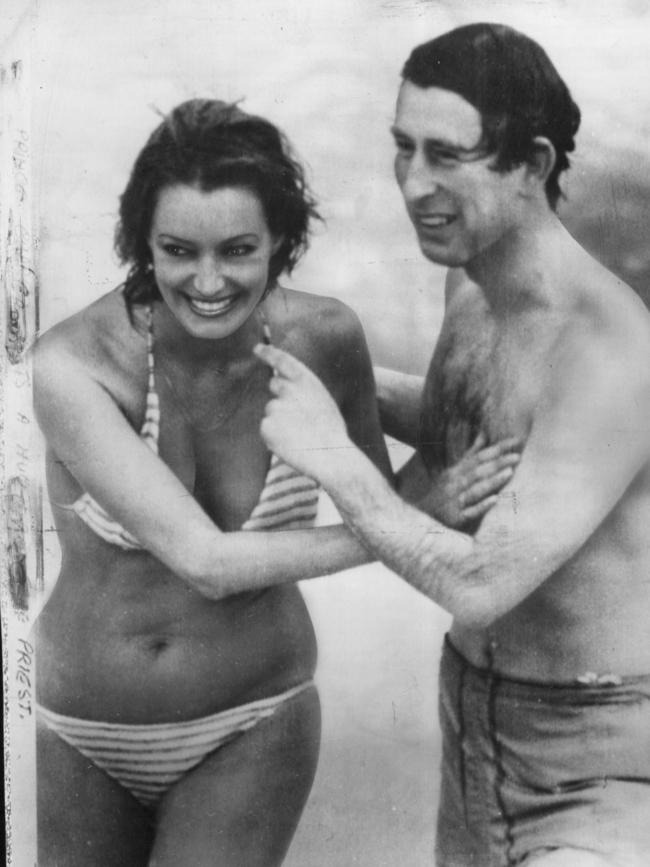

What can’t be questioned is his genuine affection for this country. His experiences on tour have been as broad and varied as the landscape, from being ambushed with a kiss by a bikini-clad model on Perth’s Cottesloe Beach in 1979 to the public triumph and private recriminations of his inaugural outing with Diana in 1983, where her star power upstaged him and provoked the jealousy that would dog their troubled marriage, by her later embittered telling.

Charles was set to speak at an Australia Day event in Sydney in 1994 when a member of the crowd fired two blank shots from a starter pistol and rushed the stage, causing bedlam. Keeping his head, then NSW premier John Fahey helped restrain the man.

As Kelly reported last year, Charles seriously considered buying a rural retreat in Australia – and this “very great desire” was taken up on his behalf by governors-general Paul Hasluck and John Kerr.

The queen ultimately baulked, fearing it would send the wrong signal about her eldest son’s priorities, but for a decade until the mid-1980s, the idea persisted that he might become governor-general as preparation for being king with the support, at various times, of prime ministers Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser.

Both before and after the epic 1975 dismissal of Whitlam’s government, Kerr offered to stand aside so that Charles could take over at Yarralumla, Kelly revealed. Fraser as prime minister “flirted” with the proposition before recognising it was untenable.

That didn’t stop another governor-general, Ninian Stephen, from reviving the idea during a meeting with Charles in Britain in the mid-1980s. Older and wiser, the crown prince said his appointment would have to carry “unanimous” political support – knowing full well it could never happen in the poisonous aftermath of the dismissal.

Charles’s longest absence from Australia spanned the saga of the collapse of his marriage to Diana, the public acknowledgment of his infidelity with Camilla, a royal divorce in 1996, Diana’s death in a car crash in Paris a year later, and his remarriage in 2005; between 1994 and 2012, he visited Australia only once.

Coincidentally or not, this also dovetailed with peak republican sentiment.

What will the next chapter bring?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout