How does a town move on from a terror attack? Lockerbie, 36 years on, is still in pain

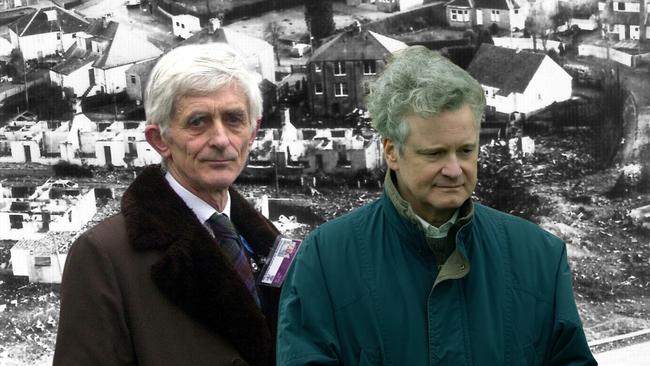

Thirty six years on from the Lockerbie bombing and it’s still unclear who was responsible. The airing of a TV series and an upcoming trial of an accused bomb maker rekindles deep emotions in the Scottish town.

How does a town survive an event so horrific, so traumatic, that it is forever linked to terrorism? Lockerbie is known not for the picturesque rolling hills dotted with sheep, the friendliness of its residents, its rural accessibility to great golf courses or the “big smoke’’ in Glasgow, but for a quirk of navigation that puts it underneath a waypoint for flights heading from London to New York.

On December 21, 1988, the shortest day of the year in the northern hemisphere, when townsfolk were either settled down in the dark and cold evening hours to watch This is Your life, or popping around for a pre-Christmas drink with neighbours, something so shocking happened that decades later some find too painful to revisit.

At 7.02pm a bomb, hidden in a cassette recorder, exploded and ripped apart Pan Am flight 103 at 31,000 feet, killing 259 passengers and crew. People on the ground heard a whistling roar that came closer and closer. A ball of fire with a trail of flame was seen in the night sky.

Suddenly in Sherwood Crescent a large dark delta-shaped object was seen to fall, and upon impact exploded into a massive ball of flame creating a 50m-long crater, obliterating houses in the hamlet, killing 11 people instantly.

Burning debris even started a blaze at the Townfoot garage 350m away. More than 20 houses were destroyed; scores of others sustained significant damage, with windows and roofs blown out.

About 600m further east, in Rosebank Crescent, a huge piece of what some thought was a comet landed smack in the middle of the road. It was the jet’s engine number three, which somehow missed houses.

This was the start of hours of chaos: hope that this mass casualty event, whatever it was, may have left survivors, then the dawning horror that it was a devastating plane disaster made even worse with the deaths of 11 neighbours.

The windows of Peter Giesecke’s house blew out and he went outside to find a woman in his hedge and another passenger still strapped in their seat on a rooftop. Shona Black Harkness said she couldn’t stop focusing on the body of a beautiful woman when she stepped out the front of the house in Park Rd she was visiting, wondering who the woman was and initially believing she was a local, not able to comprehend she had fallen from the sky.

Other shocked neighbours were highly distressed to find a child in a tree. At the time, Ms Harkness said, everyone was in shock and no one could understand that a plane had been blown apart, even though they could see burning aircraft parts and victims.

Within seconds of the plane’s disintegration the police patrol in Lockerbie had radioed the constabulary in the neighbouring town of Dumfries reporting an aircraft crash. The initial thought was a military jet had crashed, then it was thought the petrol station had exploded. Fires broke out across the town centre, and water and electricity supplies were interrupted; water had to be brought into the town on milk wagons. It took seven hours for the main fires to be extinguished.

In Dumfries, half an hour away, movie theatre staff interrupted the theatre’s film night with a call for medical personnel but the scrambling was in vain. Even the local Lockerbie photographer was left wondering why row upon row of ambulances weren’t moving until he realised, in shock, that there weren’t any survivors to assist.

Imagine the emotional impact on Colin Dorrance, just 18 and a probationary constable in Lockerbie. He was at the front of the town hall receiving debris the disbelieving locals were finding in the fields.

The first to arrive was a farmer who arrived in a pickup truck full of twisted metal, and there on the front seat a fair-haired child who looked as if she was asleep. It would be 24 years before Mr Dorrance found out the farmer was Ian Stewart, of Halldykes Farm, who had discovered the body as he searched the fields with his 17-year-old son, David, and 30 years before discovering the young victim’s name; 20-month-old Bryony Owen, who was travelling with her mother, Yvonne, from Wales to Boston.

Perhaps not knowing was not from any lack of curiosity but instead a way of coping with such a traumatic scene. Mr Dorrance said the moment had stayed with him all this time, even though he had been busy receiving other victims.

The Stewarts would find another person on their farm, 21-year-old Lynne Hartunian, one of 35 students from Syracuse University returning home to the US after studies in London.

Lockerbie residents immediately rallied around each other, setting up a 24-hour canteen for investigators, police and military officials, as well as providing a valuable place for traumatised people to get some rudimentary counselling.

There was a laundry rota set up so that all of the victims’ clothes and items – and the many Christmas presents – were cleaned before being sent back to relatives.

“It was astonishing,’’ Lockerbie councillor David Wilson told memorial history site PA103ll.org. He put his teaching career on hold in the months after the bombing to help the town recover.

“(The laundry), such a simple thing but quite emotional and very effective in bridging (closure) for some people,’’ he said.

This month new generations are learning about the Lockerbie disaster through the broadcast of the miniseries Lockerbie: A Search for Truth, based on the pursuit by grieving English father Jim Swire to find the terrorists who planted the bomb that killed his 24-year-old daughter, Flora.

Some in the town feel the series has handled the disaster sensitively; others would prefer the younger generation were able to grow up without having to cope with such a burden of history.

Visiting Lockerbie this week it becomes apparent just how damn unlucky this small sheep-grazing town in the midst of idyllic rolling hills was.

A second or two later and the plane would have missed the small town entirely.

As it was, the cockpit smashed into open fields near the Tundergarth church some 5km away, while a large amount of the plane’s debris was released in a vertical dive between 19,000 and 9000 feet directly above Lockerbie.

“The series is just one person’s story,’’ said a lady in the Lockerbie bakery on Friday.

“Everyone here has a story, it’s not something that goes away, and it’s just too painful to talk about, even now.’’

Christmas time is still difficult, says another woman, joining in the conversation.

“We didn’t put up Christmas lights for years because it wasn’t a happy time,’’ she said, adding that the wishes of the Americans to host commemorative events, and regular “adventure tourists”, “means the disaster cannot be forgotten”.

In the Lockerbie Antiques store, American tourists often come in and request souvenir pieces of aircraft metal. “I think they are surprised that it’s not some sort of Disneyland with T-shirts and memorabilia,” the storekeeper said.

Townsfolk talk about how different people have coped with the disaster in different ways: refusing to talk about it, moving away from the area, refusing to walk alone at night, corresponding and finding solace with victims’ families or, in some cases, delving deeply into the various court trials.

Yet more than three decades on, these divisions still run deep. Grieving relatives have fallen out with close friends over the $3bn compensation from Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, who insisted he had not ordered the bombing.

“Close families have fallen out about it, because some wouldn’t touch the blood money, but probably should, and others got the money who were only peripherally impacted,’’ said one of the local storekeepers.

Even family members of Flora Swire remain at odds. While Dr Swire gave up his medical practice to detail the smallest minutiae of the case over the years – he said Colin Firth’s portrayal of him in the television series was “astonishingly accurate” – his youngest daughter, Catherine, remains deeply upset. She had not wanted to be portrayed in the series and had hoped “some attempt is made to move on from incessant focus on the act of Flora’s killing, to the tragedy of her death and her need for rest”.

Catherine Swire has spoken out in The UK Telegraph against her father’s leadership and courting of cameras, saying the bomb and Flora’s death, “had blown my family apart”.

She also told the newspaper: “It was disturbing to see, in one part of the drama, the character playing my role speculate passionately about whether Iran was the source of the terror attack. That is not my voice.”

Dr Swire had remained convinced over the years that Libya was being blamed erroneously for the bombing, and would often talk to the press about his views. But Catherine said she lost her voice in the tumult of the tragedy and had turned to looking after chickens in the past 15 years to help mourn her sister.

At the Lockerbie Remembrance Garden, Craig Scott has come up from Carlisle to pay respects to Mary Lancaster, an 82-year-old resident of Sherwood Crescent who died instantly when the plane’s wings and fuselage crashed into her house, creating the 50m crater.

“She was our neighbour in Carlisle before moving to Lockerbie to be near her daughter,’’ Mr Scott said.

“I’d be kicking my football against her wall and instead of telling me off, she would come and join in, she was such a lovely lady.

“I just wanted to pay my respects to her for myself and also for my mum. In many ways it seems like yesterday that it happened.’’

Mr Scott was working for a food providore at the time of the bombing and he would bring bakery supplies into Lockerbie every day for months to help feed the large investigation team.

“It was a very sad time,’’ he said. “No one could smile.”

In the television series there is a brief scene in the first episode in which a young boy wonders what has happened to his house and his family.

This scene represents 14-year-old Steven Flannigan, who had taken his 10-year-old sister Joanne’s surprise Christmas present, a bike, to be checked by a neighbour just minutes before the explosion.

He could only watch in horror as his house in Sherwood Crescent disappeared, claiming the lives of his parents, Kate and Tom, and his sister, and he became known as the Lockerbie Orphan.

Steven could be consoled only by his older brother, David, 19, who had been in Blackpool at the time. Yet within a decade both boys would also become victims of the Lockerbie bombing: David from spending the millions he received in victim compensation and dying from the abuse of drugs and drink in Thailand in 1993; and Steven, who committed suicide in 2000 at age 24.

The TV series focuses on the involvement of the only person convicted of the bombing, former Libyan intelligence officer Abdelbaset al-Megrahi. In the coming months another man, Abu Agila Masud, who is accused of building the bomb that brought down the aircraft, is due to face a jury in Washington DC.

It is something the women in the Lockerbie bakery try to shrug off. “It just goes on and on,” one said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout