Everest and the coronation: one step higher for man and monarch

Back in 1953, British newspaper editors faced the challenge of two momentous stories to tell: the conquering of Everest and the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

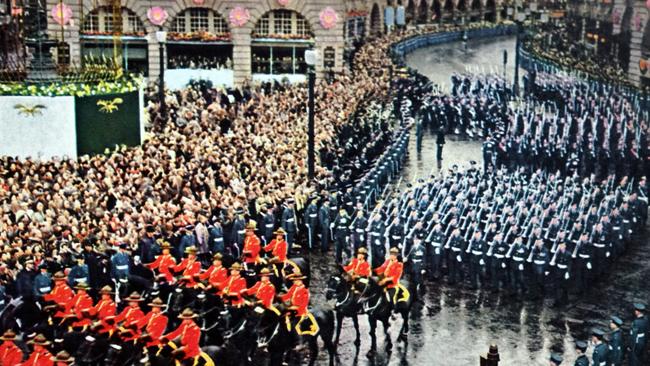

An odd ripple of applause slowly tracked the black-fingered boys with leather satchels selling newspapers to the 30-deep crowd who had gathered to watch Queen Elizabeth pass by on her way to Westminster Abbey for her coronation in 1953. The day had been planned for 14 months. But London’s weather is always an arm wrestle between hope and habit, even in summer, and most of the three million who lined the capital that day were sodden. Many men wore hats, the women headscarfs – but there were surprisingly few umbrellas.

Bored by the wait, some pushed to the front to buy one of London’s dozen morning newspapers. They didn’t know it but four days earlier Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay had climbed to the roof of the world. Their proof was a photo of Norgay at the summit of Everest (there are no photos of Hillary there; Norgay had not been taught how to operate the camera). The expedition had been sponsored by The Times and embedded in Hillary’s team was star reporter James Morris.

Once he received the message from a runner that the pair had been successful, Morris – later to become Jan Morris and an internationally acclaimed travel writer – had a telegraph operator send the following message through to the British embassy in Kathmandu and from there on to The Times office in London: “Snow conditions bad. Advance base abandoned yesterday. Awaiting improvement. All well!”

Lest anyone see the cable en route, it was in code: “Advance base abandoned” was Hillary; “awaiting improvement” was Norgay. They’d done it.

It was the biggest story of the year, but soon to be usurped. On the morning of June 2, 1953, The Times gave over page 6 to its exclusive. It stayed exclusive for an hour or so until Fleet Street saw copies of The Times’ first edition and hurriedly replicated it.

Glasgow-born Charles Wilson was then a 17-year-old cadet reporter on London’s News Chronicle, sent that day to cover the crowd on London’s The Mall that runs from Buckingham Palace to Trafalgar Square. Decades later he would edit The Times and after a visit to it in 1985 by the queen and Prince Philip he took some of us for a drink at the Blue Lion pub across the road to repeat a story he had just told Her Majesty.

Intrigued by crowd’s behaviour, he had gone to investigate. As the ink-stained boys sold their newspapers, people at the front called out to others behind them: “They’ve conquered Everest!” If any of them had a radio, it sat on a mantelpiece back home. For one of the final times, the printed newspaper was the news-breaking edge of communications.

The second Elizabethan age was about to begin. Wilson’s long life ended last August. He lived to 87 but never knew another monarch. Indeed, many men and women have lived quite full lives, the spans of which were completely encapsulated by her reign. They include Benazir Bhutto, Steve Jobs, Osama bin Laden, Carrie Fisher, Seve Ballesteros, Shinzo Abe, Anthony Bourdain and Michael Hutchence.

God saved our gracious queen for 70 years and 241 days. She had become queen on the death of her father but was not crowned for another 482 days. It was the first televised coronation and 27 million people in the UK watched it from a population of just more than 36 million.

Many of the sets were rented for the day and it was estimated 17 people watched each one of them. No one watched it in Australia. Canberra had passed the legislation paving the way for television weeks before, but we wouldn’t see flickering black-and-white images on our sets – and even then so few did – until runner Ron Clarke lit the Olympic flame in Melbourne at the end of 1956.

King Charles this weekend became the 40th sovereign to be crowned at Westminster Abbey since it hosted the ceremony and all that for Normandy-born William the Conqueror on Christmas Day 1066.

Tradition was earnestly observed with its peculiar formalities but, other than that, this weekend’s events reflected the very different world in which Charles – officially “Most Mighty and Most Excellent Monarch, our Sovereign Lord, Charles III” – will rule.

Elizabeth had reigned over an already diminished British Empire. These days the “empire” ruled by King Charles is a series of scattered pimples – Gibraltar, the Caymans, Bermuda, the Falklands and the like with a contested slice of Antarctica, over all of which the suns sets daily. Strictly speaking, the role into which he has just been ushered is a lesser one than his mother’s, notwithstanding the expanded Commonwealth of Nations, perhaps Queen Elizabeth’s most significant legacy. The leaders of its nine member states, including of course Winston Churchill and Robert Menzies, stayed in London after the coronation to begin the sixth Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting the following day. It had nine members; now it boasts 54.

Back then, British troops were fighting losing battles against independence movements in various countries, but it was nonetheless a simpler world, as was evidenced by the extraordinary investment in security across London this weekend to ensure that King Charles III and his Queen arrived at Westminster safely and returned to Buckingham Palace alive.

Charles might be unelected but he is still a target. It was often overlooked, and sometimes concealed, how often her enemies planned to assassinate Her Majesty. The IRA tried, in a clumsy Irish manner, sending a primer explosive to one operative in 1981 when the queen opened Scotland’s giant Sullom Voe oil terminal with Norway’s King Olav. But they posted the main explosive too late and all anyone heard sounded like a penny bunger.

Even when the queen visited the Republic of Ireland in 2011, the first British monarch there for a century, 10,000 of the country’s 14,000 Garda were on duty to protect her.

Perhaps the closest the queen came to being assassinated was in 1982 when 17-year-old Christopher Lewis shot at her as she passed through Dunedin on New Zealand’s South Island. He fired his .22 rifle from an elevated position in a building of the University of Otago.

At the moment he pulled the trigger he was distracted by two policemen who strolled across his line of fire. The bullet hit a street sign and many locals heard it, but police lied and said the sign had fallen over. The event was covered up so as not deter future royal visits. Also covered up was the attempt to derail the queen’s train with a log on the tracks at Bowenfels, outside Lithgow, on her 1970 Australian tour.

Charles is likely to be the subject of much more sophisticated attempts on his life and the evidence of that was clear this weekend – and it marked the most significant difference between the coronations 70 years apart. One of the reasons his simpler coronation, planned to cost less that his mother’s, ran hopelessly over budget was the need to lock down London while still giving the public access to the coronation route and their King.

The weekend’s security clampdown was codenamed Operation Golden Orb. It was in place to curb the plans of neo-nazis, jihadists and various protest groups for whom disrupting the coronation would be a supreme achievement. Roads were sealed off early and every few hours anything in which a bomb might be hidden – public bins, telephone boxes, stormwater drains – was being checked as police crews swept through the 2km coronation route that, on advice, was a quarter that of 1953. There were police in uniform and on covert patrol. Drones flew almost unnoticed across the enormous crowds to monitor for possibly hostile actors.

And it’s not just the King who was a possible target: alongside Anthony Albanese were France’s Emmanuel Macron, Pakistan’s Shehbaz Sharif, Germany’s Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Poland’s Andrzej Duda, the European Commission’s Ursula von der Leyen, US first lady Jill Biden, The Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos, Italy’s Sergio Mattarella and Canada’s Justin Trudeau.

But it all went well, and once again the world’s newspapers are celebrating the rare task of reporting a coronation.

Back in 1953, of course, newspaper editors faced a perplexing challenge. They had two momentous stories to tell. But the assistant editor of the Daily Express, Edward Pickering, showed the way, splashing with a line uttered by the editor’s exasperated secretary that night: “All this – and Everest too!”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout