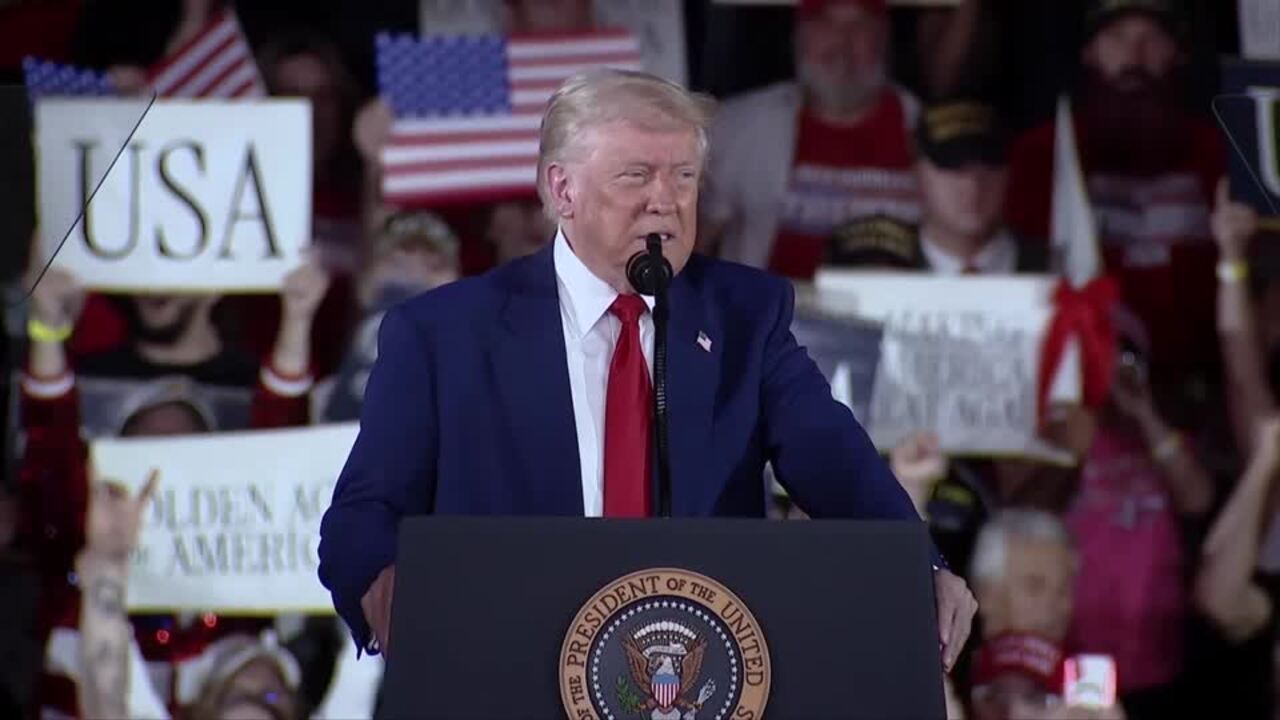

Donald Trump has no road map for remaking the global order

In his first 100 days in power Donald Trump has set about dismantling the post-WWII global order, but the President no longer believes it is America’s job to offer an alternative.

Donald Trump has used his first 100 days in power to break all the rules. He has challenged the domestic and foreign policy establishment in America and shattered the foundations of the global economic and security order.

The US President has moved swiftly to unpick institutions, test the limits of executive power, reset cultural expectations and overhaul the historic mission of the United States.

This is a new experiment and turning point in US history. While Trump is tearing down the post-World War II order, it is unclear what he is proposing as an alternative.

Where he will take America and how he will arrive at his destination are up for interpretation. But it is clear the US will no longer play the same leadership role.

While promising a pro-growth agenda, during the first 100 days the US markets have slumped, despite an initial bump after the November election win.

The S&P500 has lost more than $3.5 trillion in market value since inauguration day, with Wall Street shaken by chronic uncertainty and tariff whiplash.

Trump’s approval ratings are hovering between 39 and 45 per cent, down on the ratings for Joe Biden, Barack Obama and George W. Bush at the same stage of the electoral cycle.

Regardless of whether the Trump experiment achieves the desired soft landing or barrels out of control, it will have far-reaching consequences for America and the globe.

This includes allies such as Australia, which faces the greatest crisis in alliance management since the signing of the ANZUS treaty.

Chaotic revolution

Trump is now leading a chaotic revolution in American thought and policy which has ignited a fresh conflict about the direction of conservative politics and its values. His ascension has deepened divisions on the centre-right and galvanised a progressive resistance movement which is reshaping and influencing election outcomes overseas.

Canada and Australia are just the initial test cases.

Former Home Affairs Department secretary Mike Pezzullo says the first 100 days of Trump’s second term have been “almost an understandable period of flux – I think even more so than after the end of the Cold War, trying to put in place a strategic structure and the underpinnings of a new global order where there is no map for how to go forward”.

“It’s equally clear they are not toying with this. This is deeply felt. He is clearly of the view that he has a mandate to do this,” Pezzullo says. “They are trying to reset a whole range of strategic issues, not least the costs that they have borne for the best part of 80 years. In the absence of templates and international models and any kind of process by which to do this, it is certainly, shall we say, experimental.”

Unlike his first term, Trump 2.0 wields much greater political and personal authority and leads a cabinet filled with loyal acolytes. He has successfully taken over the GOP apparatus through sheer force of will – handing him greater control of the Republicans in Congress – and possess a greater confidence and self-belief.

He is more experienced and has quickly set about delivering his America First agenda by overseeing a major border crackdown, deporting illegal migrants, introducing sweeping tariffs, slashing the size of government, appointing Elon Musk to run the DOGE and taking on the cult of “wokeism” and identity politics.

Maximising power and authority

In doing so, Trump has created a new model of executive leadership in which presidential authority and power have been maximised – a development which poses a key challenge for the judicial branch.

He says his agenda will deliver a new “golden age of America” and increased respect for Washington, but there is little evidence these objectives are closer to realisation. Debate rages over whether Trump is a harbinger of US decline, or the architect of an American resurgence. The early signs after 100 days appear ominous.

Dennis Richardson, Australia’s ambassador to the US from 2005 to 2010, says Trump is “clearly seeking to remake government and its institutions in the US. And he is clearly seeking to remake the US role in the world since WWII”.

“I think the issue that has slowly been bubbling away, which surfaces from time to time, is the tension between the different arms of government,” Richardson says. “Over the next 12 months we may see some far-reaching rulings by the Supreme Court, and how Trump responds to those rulings will be seminal. He says that he will abide by rulings of the Supreme Court. However, I think, quite frankly, that is an open question.”

Richardson warns that Trump can “confuse occupying the most powerful political position in the world with being master of the universe”.

“I think he overestimates his own power globally,” Richardson says. “For instance, it should surprise no one that China has responded to the imposition of tariffs in the way they have. And it should surprise no one that China is simply standing its ground at the moment. At differing times, Trump almost looks as though he is negotiating with himself.”

Australia’s ambassador to Washington from 2020 to 2023, Arthur Sinodinos, says it is “hard to think of 100 days that have been as full of change and ambition on a global scale. I mean in terms of changes to the global trading and monetary system, seeking to settle conflicts on at least two continents, as well as squaring off against China.

“Americans wanted change. So he sold himself to the electorate as a change agent. And they voted for change. Whether they voted for the scale of change we are seeing now, you may raise questions about that.”

‘Art of the deal’

No coherent strategy has directed Trump’s actions, with the President acknowledging he often acts on instinct – a strength and a weakness – as he implements his mandate.

Trump has demonstrated a unique ability to pivot between dogmatic commitment to his America First agenda and pragmatic compromise – a flexibility seen as his “art of the deal” approach to politics.

“He is bringing the mind of a real-estate negotiator to geopolitical issues, and the two don’t go easily together,” Richardson says. “Some people around him and some commentators seek to bring a master plan to it all. I can’t see it. I don’t think he does think in those terms.”

Singling out one example, Pezzullo says the administration appears “unsettled” on the objective of tariffs – whether they are a permanent mechanism to ramp up domestic production and generate revenue or a temporary tool to heap economic restructuring pressure onto China.

“I don’t think they are settled on the model they are trying to build,” Pezzullo says. He argues Trump is “willing to play for very large stakes” in his remaking of the world order and is “determined not to change course” – something that could deliver great rewards or spectacular failure.

While Trump is not for turning on tariffs, it is unclear how he can deploy them while achieving his pro-growth agenda – these objectives appear in conflict. So far, Trump’s grand experiment has threatened to plunge the nation into a fresh economic crisis – with Trump refusing in March to rule out a recession – and overseen a further dismantling of the free-trade system.

Sweeping tariffs will also punish allies and rivals alike, while threatening to impose hardship and higher prices on Americans.

Sinodinos says that, while the new administration “talks about allies and partners, it divorces that from economic and trade policy. We are in a more overtly transactional world.”

He says Trump’s tariffs are appealing to “those Americans feeling left behind by globalisation” but warns there are consequences for international partners taken by surprise at the “intensity and scale of change that we’ve seen”.

Questions are emerging over the extent to which America is “moving away from being the underwriter of the global rules based order”, with Sinodinos suggesting Washington was pursuing “a more narrow set of national interests”.

Richardson argues Trump has “changed the US relationship with its traditional allies – long term”.

“It won’t matter what Trump’s successor says,” Richardson says. “There will be no immediate ‘snap back’ because of the lasting uncertainty created by him. If there is to be a rollback it will take place over a relatively long period of time. And there will need to be a very strong sense that there is bipartisanship in the US.”

‘Colossal challenge’

The clearest distillation of this new US approach came in February, when Trump berated Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky, accusing him of being “disrespectful” and reminding him that “you don’t have the cards”.

Trump’s re-engagement of Russia and rehabilitation of President Vladimir Putin in the pursuit of an end to the war in Ukraine shocked Europe and cast doubts over the future of the trans-Atlantic alliance, creating a rift that may not again be fully bridged.

Former Labor foreign minister Bob Carr says: “No one was prepared for the scale or the speed of the foreign policy transformation. America is repudiating alliances, for example, by abandoning the agreed NATO position on Ukraine.

“This is astonishing. America no longer wants to be leader of a rules-based order, but a freewheeling great power striking deals with Russia and China. This is a colossal challenge to the Australian foreign policy and security establishment, which has never contemplated, quite understandably, such a radical revision from Washington.”

While a rebalancing in the relationship with Europe to ensure it becomes more self-reliant is a positive development, European leaders fear Trump is closing the door on the continent as he redefines America’s role in the world.

This is coupled with open questions about whether Washington will follow through on plans for greater engagement in the Indo-Pacific to deter Chinese expansionism.

The risk is that Trump ends up pushing more nations into Beijing’s sphere of influence, with Richardson saying that “China’s Christmases are all coming at once”.

Sinodinos says: “Going forward, it is not clear that it will just snap back. Expectations are more baked in that allies and partners will need to do more.

“Having received this wake-up call, allies and partners may decide … (they) need other options as well, hedging and relying on other partnerships.”

US influence in Southeast Asia is on the slide, with hundreds of millions of dollars in funding being cut due to the closure of USAID and Beijing escalating its courtship of neighbouring countries.

Little progress

Trump is struggling to make progress in resolving major global conflicts, with the fragile ceasefire between Israel and Hamas collapsing and the war in Eastern Europe raging on.

Major domestic challenges remain unaddressed, with Pezzullo noting the US national debt was running at close to 125 per cent of GDP. “Last year, their payments on public debt interest … for the first time exceeded the amount they are spending on defence.”

Trump has made no serious effort to improve the US fiscal position, which is forecast to deteriorate over the next decade, while his trade war threatens to hit American communities with a new outbreak of stagflation.

Fresh doubts are also emerging over Washington’s moral character, with Trump using his platform to bully Canada into becoming the 51st state of America in an assault on the sovereignty of America’s closest partner.

Managing this new era poses unprecedented challenges for Australia, but Richardson says Canberra must not turn away from the alliance. “Whatever the negative in respect of Trump and whatever the challenges he poses to Australia, any suggestion that we should unilaterally walk away from the alliance is foolish,” he says.

Sinodinos says Australia needs to “keep finding ways to keep them engaged” and work “more overtly than we have in the past” to activate US self-interest.

Pezzullo says Australia should leverage its unique advantage – its geostrategic location, which “helps to defend America” – arguing that “we are actually contributors to American security rather than detractors from it”.

Yet the central problem remains that, after 100 days, Trump has begun remaking the global order but failed to set out what kind of world he is trying to achieve. It is the most obvious sign that Trump no longer believes this is the role of the US.

This diminishing of US leadership is the real meaning behind his plan to “Make America Great Again”. And it will take time for the world to adjust.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout