Do people in China think there will be war over Taiwan?

Beijing’s war talk has rattled capitals around the world, but many in the Chinese city closed to Taiwan say they are unconcerned.

If China’s People’s Liberation Army ever launches an attack on Taiwan, the beach I’m standing on will become the frontline of what could easily grow into the 21st century’s most destructive war.

Right now, Xiamen is one of China’s most popular tourist destinations. Much of this tidy, green city’s coastline faces the islands of Kinmen, which are ruled by Taipei and sit just a few kilometres away.

Having your photo taken with Kinmen in the backdrop, or boarding a ferry for a closer peek, is one of the top sightseeing activities in southeast China.

“So many people want to have a touch of (Taiwan), to get as close to it as possible,” a 33-year-old social media influencer from Xiamen tells me. She has just been filming herself for her online tourism channel in front of the nearby giant red characters that declare in simplified Mandarin: “One country, two systems unites China.”

It is another must-visit site on the Chinese domestic tourist trail.

Despite the propaganda, there’s a good vibe to the place. On my left, a young woman is talking to a man in a bear costume. On my right, a group of brightly dressed women from Jiangsu, a province just north of Shanghai, are striking poses as water laps at their ankles.

“We think if there has to be a war, it can be in Beijing or Shanghai. We’re a small city,” the social media influencer tells me. “We want peace. We are one family across the strait – there’s no issue that needs to be solved by war.”

Chinese investors certainly don’t seem to be pricing in a war that has been so loudly debated in Australia and around the world these past few years. Xiamen’s real estate is the fourth most expensive in China, a statistic I was told repeatedly by the city’s proud residents during my visit last week.

Leaving Xiamen on the 1hr ferry to Kinmen, ending a fascinating week in the People’s Republic just before my visa expired.

— Will Glasgow (@wmdglasgow) November 11, 2023

A shame it’s still so hard for Australian journalists to get visas, but I can understand why China’s government is so anxious. https://t.co/OemVlXxOocpic.twitter.com/s80OUID4fh

It aligns with a research paper published earlier this year by Adam Liu of the National University of Singapore and Xiaojun Li of New York University Shanghai that concluded support in the Chinese public for a war in the near term is minuscule.

Their findings were based on a survey of 2000 respondents in China, conducted between late 2020 and early 2021. They found a mere 1 per cent wanted the PLA to mount a full military invasion on Taiwan to the exclusion of less catastrophic options, such as economic coercion.

“Beijing may have more wiggle room on Taiwan than is commonly perceived,” they suggested.

China’s propaganda machine does an outstanding job of heightening fears. It routinely threatens war if the Taiwanese government doesn’t submit to its will.

However, many people in Xiamen say the dispute is nothing a bit of economic coercion can’t set right. Since 2019, Chinese tourists have not been allowed to go to Kinmen as the political relationship between Beijing and Taipei deteriorated from terrible to appalling.

“Taiwan is disobeying now so the mainland has cut off tourists. We don’t want them to make lots of money,” one man tells me. “It’s just talk, not real tension.”

View from across the strait

The tension seems worryingly real if you have been living in Taiwan in recent years. I moved to Taipei in August 2021, months after The Economist declared it “the most dangerous place on earth” – a magazine cover I tried, without success, to keep from my wife. Since then, the PLA has blasted ballistic missiles over Taiwan’s main island, launched mock blockades and buzzed military aircraft in unprecedented numbers.

This week I was among a small group of journalists given a rare briefing by Wellington Koo, secretary-general of President Tsai Ing-wen’s National Security Council. It was the first time he had ever done so, another manifestation of how unsettling things have become.

“Next year is a year of uncertainty,” he told us, gravely, in Taipei’s Presidential Office Building.

On January 13, Taiwan’s 23 million people will vote on their next president. Beijing has warned there will be trouble if they do not choose its preferred candidate.

There is nothing new in Beijing issuing threats before a Taiwanese election. However, the PLA’s capabilities have increased markedly in the first 11 years of the Communist Party’s Xi Jinping experiment.

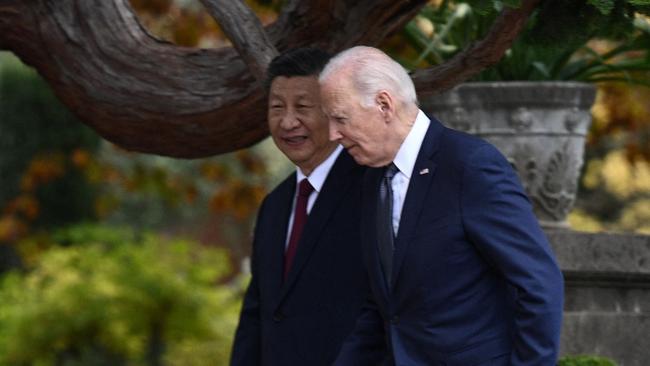

It is why Taiwan was top of the agenda during Joe Biden’s two-hour meeting this week with the Chinese leader in San Francisco.

Koo welcomed that high-level communication, saying it could help “manage risks”. It is not an approach available to Taipei since Beijing ceased all contact in 2016.

He predicted economic coercion and PLA intimation were much more likely than actual “military action” should Tsai’s vice-president William Lai win the coming election.

Beijing detests Lai and his independence-leaning Democratic People’s Party. But American efforts to increase Taiwan’s self-defences constrain China’s options.

“They are not just discussing it with us but taking action … (Our) relationship on these security issues is so close, but we must keep a low profile,” Koo said, speaking unusually frankly about Washington’s support. “I can only say, they are using all possible ways to help us, no matter if it’s in training or the build-up of asymmetric fighting capabilities.”

Xi raised US “arming” of Taiwan with Biden and made it clear that Beijing was filthy about it.

Notably, Taipei’s top security official dismissed the 2027 deadline that some American defence officials have cited as a deadline for Xi launching an invasion.

“I don’t think (China) will have such capabilities by 2027,” Koo said. Koo – a senior DPP official – said even a victory by Beijing’s preferred political partner in Taiwan, the opposition Kuomintang (KMT), would only “slightly ease” the tension.

“Maybe the level of China’s grey-zone operations will slightly ease,” he said.

We soon may get to find out if that is true or partisan spinning.

The KMT’s return to power became a lot more likely this week as it announced a campaigning partnership with an upstart party, the Taiwan People’s Party, created by former Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je.

More details of their coalition agreement will be released this weekend, but polls suggest they now may be the race favourites.

Whoever wins the election will have to respond to a Taiwanese population that has told pollsters for years it wants nothing to do with Beijing’s inflexible “one country, two systems” formula.

Xi’s the man

Not since the 1950s has Canberra been so worried about war in the Taiwan Strait.

Less than a year ago, the Albanese government sent a “strategic affairs director” to be posted in Australia’s de facto embassy in Taipei. The official used to work for Australia’s Defence Department. Euphemistically named defence attaches are becoming commonplace on the diplomatic circuit in Taipei. Even the Europeans have one.

Their capitals – whether Brussels, Canberra, Tokyo or Washington – are in a state of high alert. That is to be expected.

Xi, 70, was mostly on his best behaviour in San Francisco where, after his meeting with Biden, he dined with American business leaders who had forked out $US40,000 ($61,800) for a seat at his table.

But his one-party state controls the world’s second most powerful military and has made it clear that waging war on Taiwan is part of its official policy should Beijing decide a red line has been crossed. Ultimately, all discussions about the future of Taiwan in the Xi era return to him.

In the late 1980s, as a young comrade, Xi was the deputy mayor of Xiamen. Would he really condemn its five million-odd people to being on the front line of a major war? Would he, a man obsessed with the fall of the Soviet Union, dare roll the dice on the most complicated military operation since World War II, a decision that could bring about the end of the Communist Party’s rule of China?

People in Xiamen can’t help with the answer – in fact, many try not to think about it.

“It is up to the central government as to when and how,” one told me. “Most of my friends, we don’t talk much about this. We are busy with our own lives.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout