Taliban troops had seized Mazar-e-Sharif, capital of the northern province of Balkh, on Friday evening, two hours after breaking through defences held by government troops and militias loyal to warlords Atta Mohammad Noor and Rashid Dostum.

As Noor and Dostum fled, Taliban fighters overran the city, and insurgent columns moved on Kabul from multiple directions.

A dozen other provincial capitals had fallen in the previous few days.

Supported by guerrilla cells inside the city, the Taliban main force – with weapons seized from captured bases, riding US-made armoured vehicles or green Ford Ranger twin-cab gun trucks captured from the Afghan police – swiftly seized outlying districts.

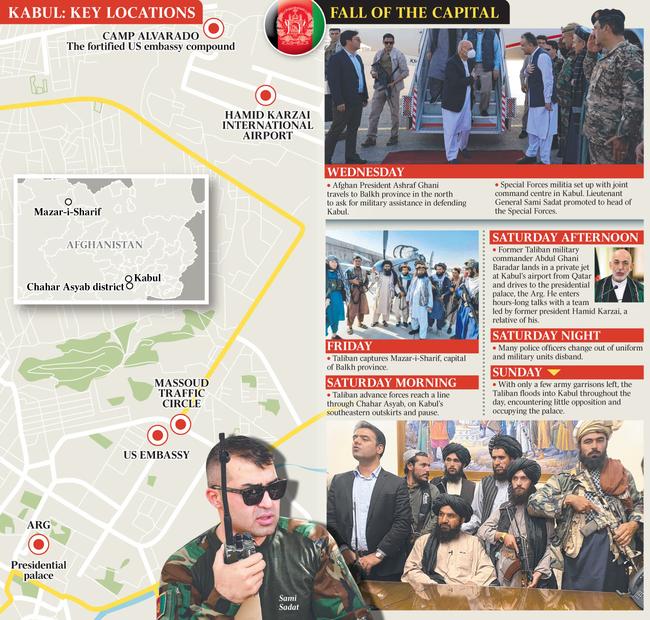

By mid-morning on Saturday, their forward troops had reached a line cutting across Chahar Asyab district on Kabul’s southeastern outskirts.

Then they paused.

Lieutenant General Sami Sadat, until recently commanding the Afghan government’s 215th Corps in Helmand, had been promoted to head Special Forces three days beforehand in a last-minute reshuffle by President Ashraf Ghani.

Ghani – who spent years systematically sidelining old-school leaders such as Noor and Dostum and marginalising their militia – had gone in desperation to Balkh on Wednesday, cap in hand, to beg their assistance.

They agreed to help but demanded a joint command centre in Kabul and official status for their militia, now to be known as “Public Forces”.

The command reshuffle was one result of that meeting, and it brought capable commanders such as Sadat – only 36 but one of the most highly regarded fighting men in Afghanistan – to command the defences of Kabul.

This account is based on dozens of phone calls, WhatsApp and text messages with individuals in Kabul and surrounding areas over recent days and nights. (Since many are now in hiding in the city, I am being cautious with their names.)

Sadat and his close friend and colleague, General Hibatullah Alizai – promoted in the same reshuffle from head of Special Forces to command the whole army – sought to stabilise the front at Chahar Asyab.

They tried to concentrate forces, hold other access points on the city’s perimeter that were already coming under pressure, maintain radio communications with units still fighting outside Kabul, keep in touch with the civilian government downtown, and somehow hold the line.

The speed of the Taliban advance had shocked everyone – except those such as Sadat, Alizai and dozens of younger commanders who fought them in Kandahar over the previous six weeks, seeing their best troops sucked into a desperate defence of the key southern city.

I too was caught by surprise: there will be time later to issue my own detailed mea culpa, but back in April I wrote it would be a stretch to imagine the Taliban taking Kabul anytime soon.

So much for that: I was dead wrong.

Writing on the wall

Commanders such as Sadat knew better: over the past several weeks hundreds of Afghan soldiers, police and civilians were killed or wounded in the defence of Kandahar and Helmand, the backbone of the army was destroyed, a third of the air force could no longer fly, and irreplaceable ammunition and fuel was used up, so that by the time the Taliban turned to Mazar and the northern cities the cupboard was bare.

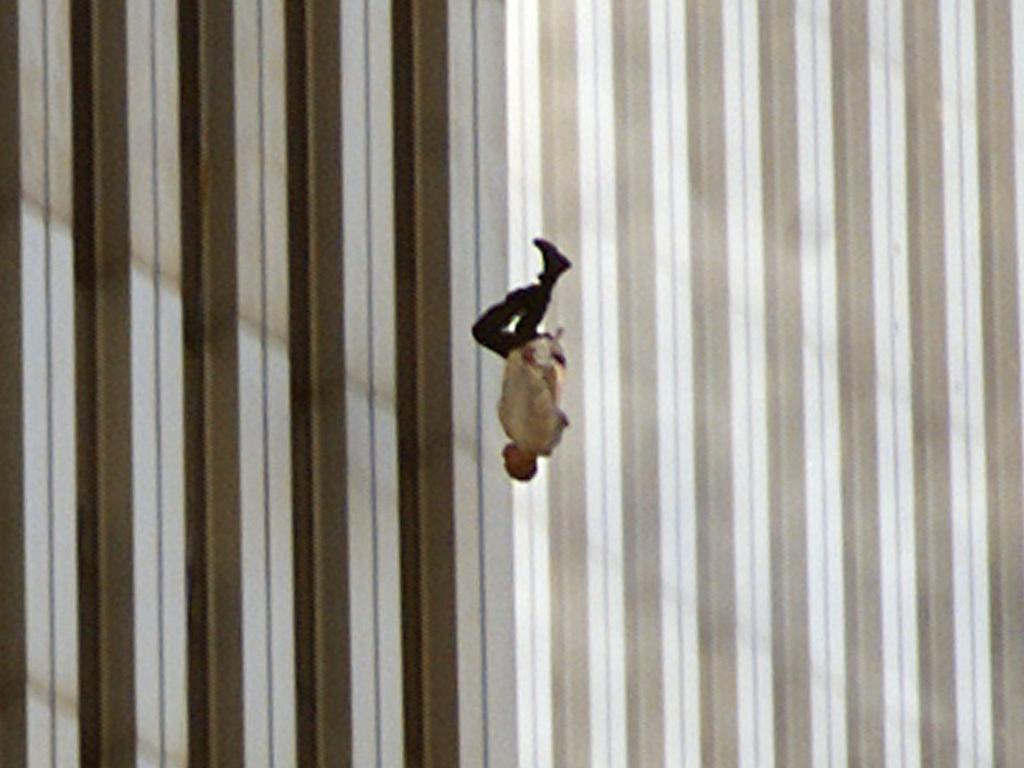

More importantly, morale was in free-fall: the sense of total abandonment by their American allies, the sudden cut-off of US air support, maintenance and logistics, and the bizarre unreality of politicians’ pronouncements left field commanders feeling betrayed and their troops with zero confidence.

Watching base after base fall to the Taliban – and, in many cases, safe passage given to garrisons who fled and handed over their weapons and ammunition – was soul-destroying.

Still, many commanders felt it would have been possible to hold Kabul, given sufficient political will. Herat, the largest city captured until the weekend, has a population of about 636,000 and fell in part because Ismail Khan, another old-school warlord, not only surrendered but allegedly switched sides.

(Friends on the ground could not confirm this on Saturday; some claim he was simply captured.)

By contrast, Kabul has 4.8 million people, was the centre of Ghani’s government, home to international delegations from NATO, the UN, allied militaries, and embassies of countries that had been pledging continued support since the US withdrawal began.

It was also a major garrison for the army, the police and Afghanistan’s intelligence service, the NDS. Many troops pushed out of other places had come to Kabul and Sadat, Alizai and the other commanders were now fighting close to supply bases and just a few minutes’ flight time from their last remaining air base, at Kabul airport, where all the surviving combat aircraft and aircrews were based, along with what limited stocks of bombs and rockets remained.

The supply problems, over-extended deployments across far-flung bases, and lack of air support they had suffered for months would all become far less difficult now, as long as the politicians held their nerve and the international community kept its promises.

It was not far-fetched to think that the Afghan forces could hold the city, resupply across short supply lines through the airport, concentrate their remaining airstrikes on enemy massing on the city’s approaches, exhaust the Taliban (which, after all, had far fewer fighters than the army) and turn the tide.

It might take days or weeks, but it could be done. This, at any rate, was the view of some commanders, intelligence officers and civil servants on the ground as recently as noon on Saturday.

The key moment

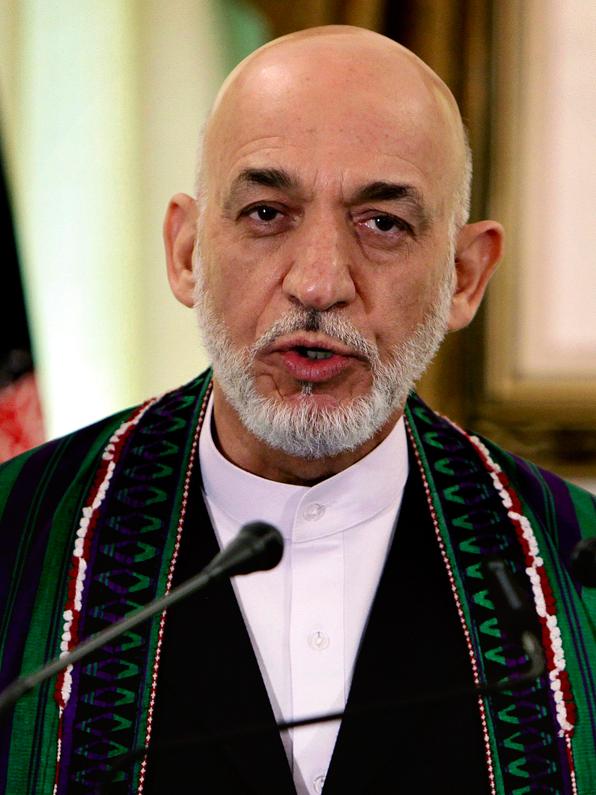

But the Taliban pause was no accident. Late on Saturday afternoon, a private jet from Qatar landed at Kabul airport. Abdul Ghani Baradar, former military commander of the Taliban and now head of its negotiating team in the Qatari city of Doha, descended from the plane and drove to the Arg, the presidential palace in downtown Kabul, where he disappeared into hours-long talks with a team led by former president Hamid Karzai.

Baradar and Karzai are relatives – members of the Popalzai tribe – who have known each for decades and negotiated many times since 2001. The sidelining of Ghani, whose dismissal has long been a key Taliban demand, could mean only one thing.

Word immediately went out on WhatsApp to those holding the line: “Baradar is at the Arg.”

The government was negotiating a transition of power to the Taliban – under what face-saving conditions, if any, was still unclear – but whatever the terms, the government was clearly collapsing. It was over.

As night fell on Saturday, NDS operators scattered to safe houses and began evading. Police changed into civilian clothes and tried to slip away.

Military units melted. Some simply went home. Others tried to make it to the Panjshir Valley, north of Kabul, still held by strongly anti-Taliban forces under the Massoud family and their allies, who have offered safe haven to anyone fleeing the Taliban and are vowing to fight on.

Isolated garrisons still held out, and commando troops continued operating outside the city. Alizai and the other field commanders stayed at their posts with a shrinking but still loyal core of capable units.

By Sunday night, commanders’ phones were down and their status was unknown. Civil servants, families of senior officers, prominent women likely to be targeted, and others were hiding. Some were in such insecure places that they had notifications set to say they could text silently but not talk.

Final assault

The Taliban flooded into the city throughout Sunday, encountering little opposition and inflicting little violence. Its men rapidly occupied the palace, giving press conferences and hoisting their white Shahadah flags over government offices and landmarks such as the Massoud traffic circle in front of the US embassy.

The embassy was abandoned, flag lowered, helicopters shuttling US civilian staff to Camp Alvarado, the fortified embassy compound on the airport grounds, from where C-17 transport planes airlifted civilians out and brought Marines and Airborne troops in to secure the chaotic evacuation of the international players, whose words of assurance proved so empty.

Western allies began scrambling to pull out their people, and closed their embassies.

Two major diplomatic posts that remain open are the Chinese and Russian embassies: both countries have suggested they may soon recognise the Taliban government. Former president Karzai seems to still be in the presidential palace.

President Ghani, National Security Adviser Hamdullah Mohib and other politicians boarded a helicopter near the palace at 2.47pm on Sunday, then flew out of the city as Taliban fighters swarmed the airport road.

One of their staffers, carrying Ghani’s personal bags, ran for the helicopter but missed it. He was left, holding the bag, on the landing zone.

For a moment on Saturday, it looked as though Kabul might actually hold.