In a rare diplomatic failure for Beijing, the South Pacific island states refused to sign up to its proposed regional trade and security agreement.

Nevertheless, Beijing is in this for the long haul.

Anthony Albanese, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and the entire Australian national security establishment understand this.

Albanese leaves for Indonesia at the weekend, an important early visit. Indonesia, our most powerful neighbour, though it is not showing much interest in us at the moment, is typically the first nation a new Australian prime minister visits.

Yet Albanese was absolutely right to travel to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue summit in Tokyo just two days after Labor was elected to government.

He would have included Papua New Guinea on the Indonesian trip, except that PNG is now in the midst of an election campaign and the government there is in caretaker mode.

To travel to PNG in this period would be inconvenient to our hosts, and could be construed as attempted interference in PNG politics.

That China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, who arrives in Port Moresby on Thursday, is visiting PNG precisely during this time has led to serious criticism from PNG’s opposition politicians.

In opposition, Albanese and Wong promised to put greater emphasis on both the South Pacific and Southeast Asia. Wong’s hurried and seemingly effective visit to Fiji, and now Albanese’s to Jakarta, give effect to both those agenda items, but it is certainly to the South Pacific where the most urgent and extensive Australian attention will need to be directed.

The multilateral agreement to which Beijing failed to get the South Pacific to sign up was important, but it’s actually far less important than the bilateral agreements it will try to do along the lines of its agreement with Solomon Islands.

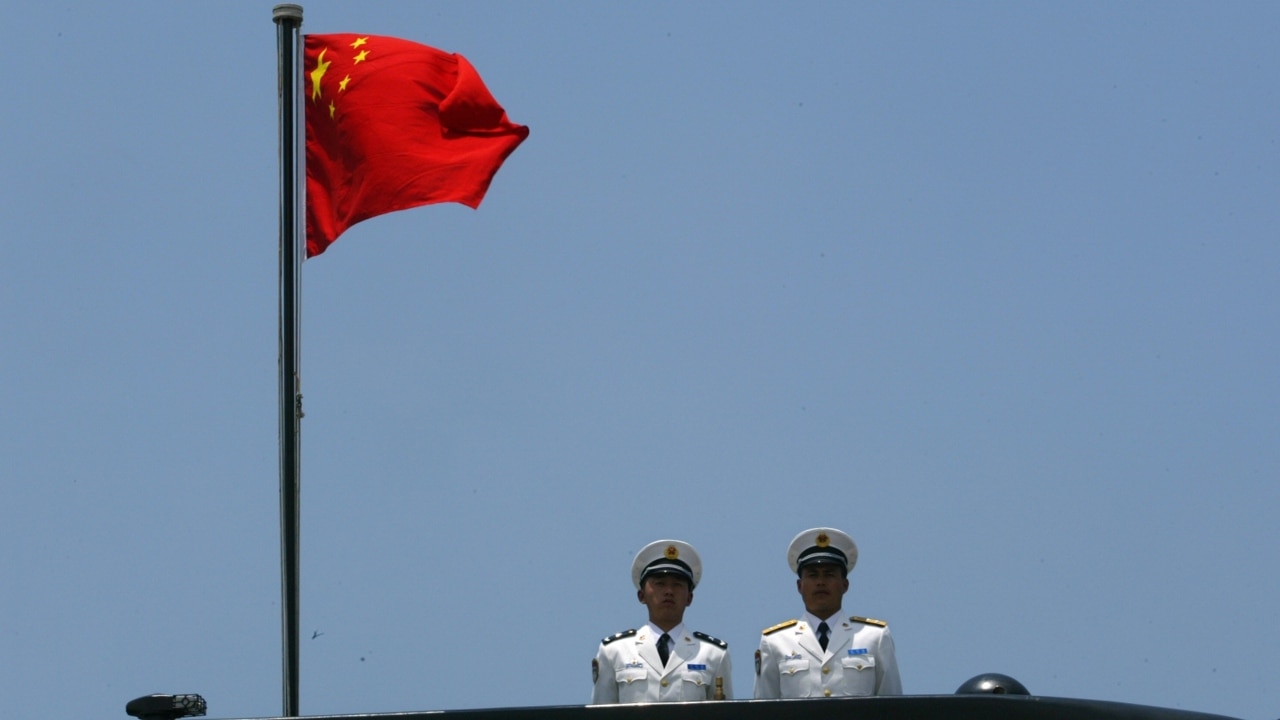

For more than a decade, Australian intelligence agencies have understood that Beijing, despite its many denials, wants to establish a military base in the South Pacific. This will only come about through a bilateral agreement, even an ambiguous agreement, and a creeping Chinese presence.

The purpose of the multilateral agreement is nonetheless political, to normalise Chinese interference in South Pacific security affairs. The strategic reward for Beijing in achieving a military base is enormous – neutralising Australia’s military, threatening future US military deployments, projecting power across the Pacific region.

Beijing will not give up this ambition. It is far more concrete and specific than its general Belt-and-Road influence-peddling diplomacy. It is the only reason Beijing is devoting so much attention to the Pacific.

This is the right time for the Albanese government to think big and ambitious in its South Pacific policy.

Although it would need to be done with care, a substantial widening of the Pacific labour program would be good for Australia economically and a powerful glue with the region, producing cultural and strategic dividends.

Probably there are no circumstances more propitious for such an initiative than now. Who could oppose it?

Finally, the paradoxical scheduling of the Quad summit has been an enormous boon to the Albanese government in allowing it to focus unashamedly on high stakes international issues.

The government was elected substantially on a domestic agenda, and the Liberals lost a lot of seats on climate issues, but the government has had to attend to the most urgent, traditional security issues in its first week.

This is helpful in underlining for the Australian people that this is indeed a core task of government, and one that will only grow in importance.

Australia has won the first round of the great South Pacific heavyweight bout, but only the first round … and it’s at least a 15-round bout, although it may be even much longer than that.