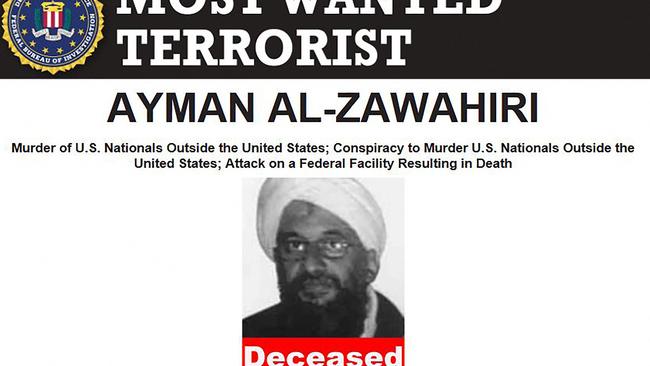

Assassination of 9/11 mastermind Ayman al-Zawahiri a win but the war goes on

Ayman al-Zawahiri’s death marks the end of the Osama bin Laden era of terrorism but it raises questions about what comes next. It has exposed the lies of the Taliban government and raised fears that history might repeat itself.

By the time the 71-year-old Egyptian doctor was extinguished by a US Hellfire missile this week, Zawahiri would have barely recognised the current state of the Islamic terrorist movement that he helped to create.

He was still the head and co-founder of al-Qaeda, once the world’s most feared terrorist group. But since Zawahiri assumed control of al-Qaeda in 2011 on the death of bin Laden, the global Islamic terror movement has splintered and morphed into a very different beast to the cohesive group that planned and carried out the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington in 2001.

First, al-Qaeda, while still dangerous, is a shadow of its former self. After bin Laden’s death, Zawahiri struggled to exert centralised control of the group from his remote Pakistan hideouts as he evaded the US manhunt for him.

He would make the occasional motivation video, damning the West and praising the jihadist cause, but he no longer had the networks, communication or ability to plan and carry out a major attack in Western countries. The last major al-Qaeda attack on the West was the 2005 London bombings that killed 52 people.

This does not mean al-Qaeda is no longer dangerous. On the contrary, it has splintered into a series of semi-autonomous and highly active regional groups in Africa and the Middle East. But so far these groups have been preoccupied with attacks on local populations, rather than Western countries. And it is unclear how much influence Zawahari had on them.

Under Zawahiri’s watch, al-Qaeda lost its status as the world’s most dangerous terror movement to its rival Islamic State (which ironically began as an al-Qaeda offshoot). Islamic State captured the imagination of a new generation of extremists with its slick publicity, gruesome videos and its declaration of a caliphate in 2014 stretching across large swathes of Syria and Iraq.

It has been Islamic State, not al-Qaeda, that has led or inspired major attacks on the West in the past decade despite that group being soundly defeated on the battlefield and losing its caliphate by 2018. So today’s Islamic terrorism movement is a much more disparate and localised beast, split between Islamic State and al-Qaeda, which detest each other. Both groups are seeking to rebuild themselves to the point that they can once again strike the West.

The death of Zawahiri is a coup for the US and one that will help to bring closure for the families of his many victims. But it also provides an opportunity for a younger and more charismatic leader to emerge, and it raises uncomfortable questions about Afghanistan’s role in once again harbouring terrorists.

There is no clear successor to Zawahiri. The most likely heir, Saif al-Adel, an al-Qaeda veteran who fought the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, is believed to be in Iran alongside the group’s No.3 and its general manager, Abd al-Rahman al-Maghrebi. But al-Qaeda has strong and largely autonomous leaders in its various divisions, including in Africa and the Middle East.

These include Maghrebi, who is also Zawahiri’s son-in-law; Yazid Mebrak, who heads up al-Qaeda in northwest Africa; Ahmed Diriye, the emir of al-Shabab, al-Qaeda’s branch in East Africa; and Khalid Batarfi, head of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

The question is whether the terror group can agree on a single overarching leader or whether it will splinter into separate groups based on geography as much as ideology.

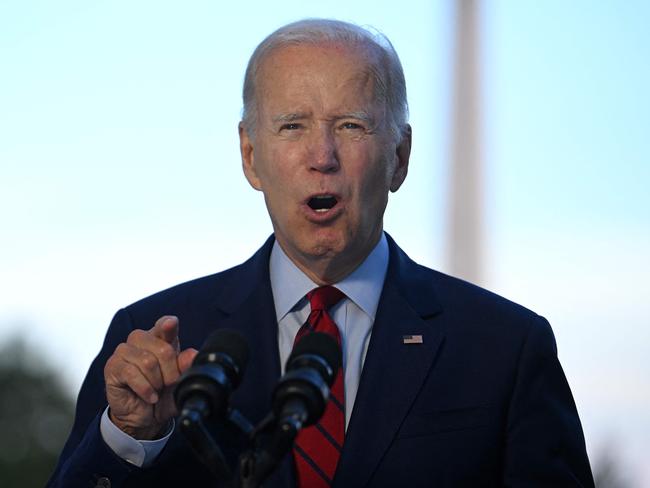

US President Joe Biden has sought to portray Zawahiri’s death as justification for his much criticised withdrawal of US troops in that country in August last year. He argues that Zawahiri’s death proves his claims that the US can prevent Afghanistan once again becoming a safe haven for terrorists by “over the horizon” strikes like the long-range drone that took out Zawahiri.

But the reality is much murkier. Zawahiri’s death has punctured any fantasy that the Taliban government can be trusted to adhere to its 2020 Doha agreement not to provide sanctuary to terror groups. This agreement was a key condition for Biden’s withdrawal of American troops. But Zawahiri was found in suburban Kabul, hiding in plain sight and living in a house owned by a key aide of a senior Taliban government official. The Taliban took steps to hide the fact that Zawahiri was in the house.

“Was there ever really a prospect for laying a foundation for the US and Taliban to coexist peacefully or for us to have a real relationship with the regime?” asks Kate Bateman, an Afghanistan specialist at the US Institute of Peace. “Their ideology is aligned with a jihadist narrative.”

The protection given to Zawahiri by the Taliban offers proof that this Taliban government will not be a softer, more pragmatic version of the one that ruled the country 20 years ago.

“Zawahiri’s presence in post-withdrawal Afghanistan suggests that, as feared, the Taliban is once more granting safe haven to the leaders of al-Qaeda – a group with which it has never broken,” says Nathan Sales, co-ordinator for counter-terrorism during the Trump presidency who is now at the Atlantic Council.

The White House has not said how it will respond to the Taliban’s decision to harbour Zawahiri, but the prospects of a workable relationship look precarious.

“The Taliban has a choice now,” White House national security spokesman John Kirby says. “They can comply with their agreement under the Doha agreement … or they can choose to be going down a different path. And if they go down a different path, it’s going to lead to consequences not just from the United States but from the international community.”

The Taliban’s rogue behaviour comes as it is negotiating with the US to release at least $US3.5bn ($5bn) of Afghan central bank reserves held by the US.

“I think Zawahiri’s presence in a Taliban safe house has to be the nail in the coffin of any plan to release funds directly to the Taliban,” says Sales. “They simply can’t be trusted and the risk is substantial that money released to them would find its way inevitably and directly into al-Qaeda’s pockets.”

As the 12-month anniversary of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan approaches, al-Qaeda has reportedly begun to establish training camps in remote rural districts in the country’s east.

But a UN report released last month says the group’s activities there do not yet pose a threat outside of the country.

“Al-Qa’ida is not viewed as posing an immediate international threat from its safe haven in Afghanistan because it lacks an external operational capability” from there “and does not currently wish to cause the Taliban international difficulty or embarrassment”, the UN report states. It states that neither Islamic State nor al-Qaeda “is believed to be capable of mounting international attacks before 2023 at the earliest, regardless of their intent or of whether the Taliban acts to restrain them”.

The US Director of National Intelligence said earlier this year that al-Qaeda would consolidate in Afghanistan before it sought to attack the West again.

“Al-Qa’ida probably will gauge its ability to operate in Afghanistan under Taliban restrictions and will focus on maintaining its safe haven before seeking to conduct or support external operations from Afghanistan,” the DNI said.

The most significant terror threat in Afghanistan now is not al-Qaeda but a local offshoot of Islamic State known as Islamic State- Khorasan Province, or IS-K. The Sunni extremist group carried out the bomb attack near the Kabul airport during the US withdrawal in August last year that killed 13 US troops and dozens of Afghans and it has become more active in the country’s north and east.

However, unlike al-Qaeda, IS-K is an ideological opponent of the Taliban and has attacked the Taliban directly as well, as mosques and schools and weddings targeting mostly Shi’ites. So far IS-K has not extended its terror ambitions beyond Afghanistan.

The concern for the US and its Western allies is that the Taliban will continue to give sanctuary to al-Qaeda, giving the group an opportunity to regroup under new leadership. And although Biden has rightly claimed a victory for his strategy with the assassination of Zawahiri, there are limits to what Washington can do to curtail al-Qaeda if the Taliban continues to give it sanctuary.

“The President has made good on his word when we left,” national security adviser Jake Sullivan says. “After 20 years of war to keep this country safe, he said we would be able to continue to target and take out terrorists in Afghanistan without troops on the ground.”

But the former head of US Central Command in Qatar, General Kenneth McKenzie, has conceded that US intelligence visibility in Afghanistan today is barely 1 per cent of what it was when US troops were there. McKenzie says the US was well aware before Zawahiri’s death that al-Qaeda was seeking to establish new training camps inside Afghanistan. “I see nothing happening in Afghanistan now that tells me that the Taliban is determined to prevent that from happening,” he says.

As Zawahiri’s death proved, precision drone strikes are useful to threaten and at times kill terrorist leaders. But the circumstances of Zawahari’s death made it unusually suitable for a drone attack. US intelligence knew the house he was hiding in and knew his daily pattern was to read early in the morning on an exposed balcony. Most terror leaders make themselves a far more difficult target.

“This was a unique circumstance,” says McKenzie. “You had a target that didn’t move, and they had the opportunity to get a good look at (his) pattern of life. That’s not always going to be the case. In fact, typically that is not the case.”

The other problem is that the intelligence underpinning drone strikes can often be wrong. As the US was evacuating from Afghanistan in August last year, an errant drone strike based on wrong information in Kabul killed 10 civilians.

The drone strike against Zawahiri was the first launched by the US since its withdrawal from the country.

News of Zawahari’s death was well received in the US, especially by the families of the almost 3000 people killed in the 9/11 attacks, but it is unlikely to be of lasting political benefit to Biden ahead of the November midterm elections.

The raid that killed bin Laden in 2011 brought only a brief bump in the polls for president Barack Obama, while the 2019 killing of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had no impact on Donald Trump’s approval ratings.

In fact, Republicans, who were heavily critical of Biden’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan, are already moving to capitalise politically on the revelation that the Taliban government is once again harbouring terrorists.

Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell says: “Killing al-Zawahiri is a success, but the underlying resurgence of al-Qaeda terrorists into Afghanistan is a growing threat that was foreseeable and avoidable.” It “further indicates that Afghanistan is again becoming a major thicket of terrorist activity following the President’s decision to withdraw US forces”.

Zawahiri’s death is an important win for the war against terrorism. But it has exposed the lies of the Taliban government and raised fears that history might repeat itself as al-Qaeda once again seeks to exploit the safe haven of Afghanistan to rebuild its might.

The assassination of 9/11 mastermind Ayman al-Zawahiri marks the end of the Osama bin Laden era of terrorism but it raises critical questions about what comes next.