Wrecked: how did Queensland’s island resorts come to this?

Once the country’s best-known resort looks like an apocalypse film set, the ‘shameful secret’ of Australian tourism.

Benny Christopher stands on the beach on Queensland’s Great Keppel Island and looks across to the sprawling ruins of what was once the country’s best-known tourist resort. In front of him is something that could pass as a film set for a movie about the apocalypse. More than 500 broken and abandoned hotel rooms are wrapped around a hill once boasting sweeping sea views for a lost generation of holiday-makers seeking to “Get Wrecked” on Great Keppel. Broken glass is strewn inside the rooms, doors dangle precariously on rusted hinges, mattresses lie randomly in the grass. The abandoned swimming pools are half full of mud. The forest has gained the upper hand in the 14 years since the resort shut down, weaving its green shoots through the ruins of this broken dream, reclaiming what locals dub a “shameful secret” of Australian tourism.

“Just look at that, it’s an absolute joke that it’s allowed to sit there and rot away,” says Christopher, a local resident who, with his partner Sara Baines, manages one of the half a dozen tourist accommodations still operating on Great Keppel. “Every few years someone comes to this island and says they’re going to rebuild it and everyone gets excited and blah blah blah then nothing happens and everyone gets cranky again. And then another rich person rolls up in a helicopter with a fancy pen and makes a big show of it all over again.”

The latest rich person to roll up on Great Keppel can afford more than a fancy pen. Her name is whispered through the palms as locals ponder whether Gina Rinehart will become their island’s white knight or yet another false dawn for the resort that hosted its last guest in 2008.

“For Great Keppel I feel this is the last roll of the dice,” says local pizza shop owner Gerry Christie about the Rinehart bid, which would see the construction of more than 800 luxury apartments and villas, an upmarket retail precinct and a 250‑berth marina. “With everything that has happened to this island I just think how lucky we are to have the richest person in Australia wanting to invest more than $2 billion. If Gina can’t do it, it can’t be done. It would future-proof central Queensland for 20 years but more importantly it would catapult all those other island resort owners to start fixing things.”

When Christie talks about island resort owners “fixing things” he is talking about a string of “shameful secrets” that extend far beyond Great Keppel Island, off the Capricorn Coast at the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef. “The terrible truth is that a lot of the Queensland island resorts have been abandoned and are in a disgraceful state of dilapidation,” says Geoff Mercer, who has lived on Great Keppel on and off since 1978. He counts them on his fingers: “Great Keppel, Dunk Island, Hinchinbrook, Brampton, South Molle, Lindeman.” He fails to mention abandoned coastal resorts including the Capricorn Resort in Yeppoon or Laguna Quays near Airlie Beach.

All of these former resorts, many once household names, are rotting in the tropical sun, casting a shadow over Queensland’s once-proud image as a tourist mecca for those in search of an island paradise. Some have been ravaged by cyclones, others have been forgotten by their Chinese, Japanese or Australian leasehold owners, and all have been victims of excessive red tape and the intransigence of the Queensland Government, which owns the land upon which the bones of these resorts are rotting. “Ultimately the state government owns the land so they are the landlord and are responsible for finding a solution [because] the Great Barrier Reef islands are magnificent, there is nothing like them in the world,” says Mary Carroll, CEO of Capricorn Enterprise, which markets the Capricorn region of central Queensland to tourists.

Amanda Camm, the LNP state member for Whitsunday, shares Carroll’s disgust at the neglect of Queensland’s iconic island resorts. “These islands are unique, they are an incredible natural asset and it’s just appalling that the state government has allowed them to sit there in rack and ruin. They don’t want to take accountability. It’s easier to pretend they are not there.” Camm is one of a growing chorus of voices that hounded the Palaszczuk Government to hold an overdue inquiry into the failures of so many island resorts. That inquiry, which is due to report in August, will look at the role of these ventures in attracting tourists and the obstacles to their success, from costs to red tape to infrastructure.

Queensland tourism minister Stirling Hinchliffe claims the state’s $23 billion tourism industry is bouncing back after the pandemic but admits the island resorts face myriad challenges. “Operating costs are significantly higher than for mainland operators with greater remote workforce expenses on top of electricity generation and potable water infrastructure, waste treatment and removal and reliance on aviation and water transport for food and supplies,” he says. “Natural disasters such as cyclones and higher insurance costs have also impacted island resorts.”

Finding a solution is complicated by the fact they are so different. A number, such as the large Hamilton Island Resort and luxury properties on Lizard and Hayman islands, are thriving. Direct air connections give Hamilton the large tourist numbers needed to justify the costs while those resorts that offer extreme luxury attract a smaller super-wealthy and celebrity crowd that can afford to pay over-the-top prices to keep them viable. But elsewhere, the story is grim. Brampton Island resort has been closed since 2010 when it was bought by United Petroleum, owned by Australian businessmen Avi Silver and Eddie Hirsch, and it has been left to rot. South Molle Island resort has sat dormant since Cyclone Debbie destroyed it in 2017; its Chinese owners, China Capital Investment Group, have been sitting on the abandoned property. Dunk Island has been empty since Cyclone Yasi struck in 2011. Its Australian owner, Linc Energy founder Peter Bond, bought it in 2012 and has tried unsuccessfully to sell it several times. Lindeman Island resort has been closed since it too was hit by Cyclone Yasi; Chinese company White Horse Group purchased it in 2012 but has not redeveloped it.

Hinchinbrook Island resort, south of Cairns, has been rotting away since it closed in 2010, while the Capricorn Resort in Yeppoon closed in 2016 with its Japanese owner The Iwasaki Group refusing to reopen it. Meanwhile, Laguna Quays Resort, which closed in 1995, was purchased by Chinese construction company Fullshare Group in 2013 and has never reopened. Many of these resort owners are “land banking” – sitting on their properties until they can sell for a profit.

The wrecked resorts are not just an ugly blight on beautiful islands, they are a physical reminder of a shameful lack of accountability from owners and government. Whitsunday MP Camm says there should be a “use it or lose it” rule for long-term lease holders. “I don’t believe we should have six to 10 island resorts sitting abandoned out there with a 50- or 60-year lease held by foreign and other companies that have little or no intention to develop them,’’ she says. “If they can’t make it work then we should review those leases and see what other market opportunities are out there.”

“To say what has gone wrong is difficult,” says Brett Fraser, the CEO of the Queensland Tourism Council. “Island resorts really put Queensland on the map with international visitors but they are difficult to run. We need more investment and infrastructure, less red tape and greater co-operation between different levels of government.”

The advertisement sounds seductive: “Five-star luxury with all-inclusive-dining, nightly cocktails, and kids stay free”. Photos show swaying palms and frangipani trees shading a tropical beachside oasis where your toughest decision of the day is whether to opt for the private cabana on the sand or a lounge at one of the five resort pools. Throw in a couple of free massages, a kids’ club and airport transfers and your all-inclusive seven nights in a garden view suite will come to $1999 for two adults and two kids under 12. Another $800 will cover your flights. To Bali. How can north Queensland compete with this?

Capricorn’s Mary Carroll says Queensland’s island resorts are being undercut by cheaper resorts overseas. “What has occurred over the past couple of decades is that the cost, the approvals process and the wages are much higher in Australia and especially on the Great Barrier Reef while in developing countries like Indonesia they can construct up to six six-star resorts a year, often with airfares that are cheaper.”

In his submission to the Queensland government inquiry Glenn Bourke, chief executive officer of Hamilton Island Enterprises Limited, says running an island resort is an “expensive proposition” and he offers a dizzying list of obstacles faced by the operators. “Hamilton Island must pay local rates, state rent and commonwealth lease fees. These fees are not in isolation to other regulatory costs. For example, moorings require a permit from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Maritime Safety Queensland, both having their individual requirements. Island resort operators are faced with further difficulties trying to manage a workforce under the current modern award systems. Hamilton Island is a seven-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day operation, with 21 different awards that apply to the workforce on the island. Island communities do not have the luxury of having a general population as a source of employees and as such they are reliant on a small pool to draw from for their staffing.”

Any plans to revive island resorts also need to take into account the views of conservation groups and indigenous custodians. Most conservation groups only support their revival if they are eco-friendly and fully sustainable, protecting the natural values of the area. Similarly, indigenous custodians such as the Woppaburra people on Great Keppel want a say in the way resorts are redeveloped. The Woppaburra were formally recognised as native title holders of the Keppel, or Woppa, islands in December and elder Bob Muir says he has already met the Hancock Prospecting team. “It really is something where, if we’re included at the beginning, it’s going to help us understand what’s going to happen to the area,” Muir said in February. “The bottom line is no matter who comes in, I’m always worried and concerned.”

But what if, after all this effort, travellers don’t return in sufficient numbers to make it all worthwhile? Pierre Benckendorff, an associate professor in tourism at the University of Queensland, says tastes have changed and many Queensland island resorts may no longer offer what travellers want. “What might have been a good island resort experience back in the 1990s is just not going to cut it anymore when you look at some of the five-star experiences you can have in Bali for pretty much the same price. It’s sad to see the state that some of those Queensland island resorts are in.”

In his submission to the government’s inquiry, Whitsunday resident Elmer Ten-Haken argues that with a few exceptions, such as Hamilton and Hayman, the era of Queensland island resorts is over. “No new resorts should be built on any of the Whitsunday Islands,” he writes. “There is no justification for them and, it would seem, little demand either. If there were, we wouldn’t have five abandoned ones. The history of resorts in the Whitsundays shows that running them is difficult and costly and that fashions in tourism change all too quickly – leaving us with stranded assets.” Ten-Haken argues that owners of island resorts have consistently underestimated the costs of running them as well as the dangers of cyclones and persistently strong winds. “Clearly the expense, difficulty and discomfort of getting guests, staff and supplies to these islands, the limited experiences which they provided, plus the privations of mother nature and the changing expectations of visitors killed off many of the big resorts. So now we have a whole lot of islands with ruined and abandoned resorts on them,” he writes.

Even Queensland’s Department of Resources admits, in dry public-service speak, that so many abandoned resorts are not a good look for Queensland’s tourism industry. “Currently, some Great Barrier Reef island resorts are not operating,” the department says in its submission. “Abandoned and closed resorts are an important consideration for the government in continuing to secure the Great Barrier Reef’s iconic reputation and flow-on benefits to tourism and other sectors. Closed resorts can result in environmental damage… and attract negative media attention, which impacts on perceptions of the Great Barrier Reef and the broader Queensland tourism brand.”

One of several dozen residents on Great Keppel Island, Geoff Mercer has lived the giddy heights and the bankrupt lows as the island went from its glory days in the ’80s and ’90s to having no major resort since 2008. “Great Keppel is still open for business and is very popular,” says Mercer, who runs the two-star Great Keppel Island Holiday Village. “But we’ve all suffered from people’s belief – fuelled by inaccurate media reporting – that once the resort shut, the island was closed. It’s been tough.”

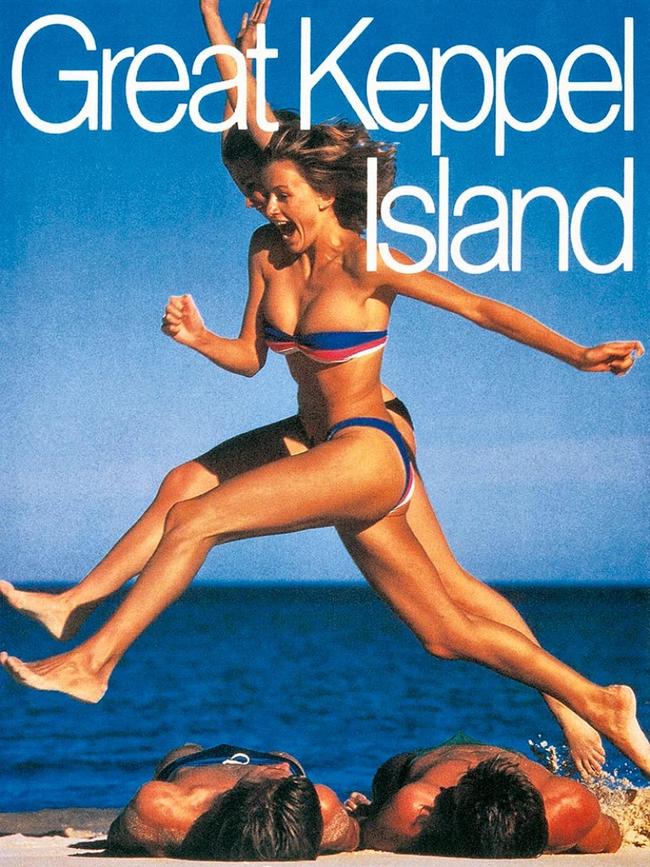

Mercer was there from the beginning, running his own holiday village near the resort as the hugely successful “Get Wrecked” advertising campaign lured tens of thousands of holiday-makers to the main island resort, which was owned by the now defunct airline TAA and then by Qantas. “Great Keppel Island, when I arrived on it at 25 years of age in 1978, was magical – just the ocean, the amazing beaches, the beautiful weather and lots of space,” Mercer recalls. Performers including Blondie, Skyhooks, Joe Cocker, Australian Crawl, Jimmy Barnes and Darryl Braithwaite would play gigs at the resort. “It was old-style entertainment, but it was fun,” he says. “The resort was based on a Honolulu Gilligan’s Island theme with Hawaiian leis around your neck, seafood nights and entertainment and games.” But he says the resort became tired in the 1990s. “AIDS was around and everyone literally zipped up and went home.”

Around 2002, Contiki took over the resort and tried to attract an 18-35 youth market promising “sun, sand, sea and sex”. “That period was a complete nightmare,” says Mercer. “We would hear ‘doof-doof’ music until 3am every night. And it failed badly as a business idea.”

In 2006, Australian property tycoon Terry Agnew’s Tower Holdings paid $16.5 million for the leasehold before shutting the resort down in 2008 amid the global financial crisis. The closure almost sent Mercer broke. “The phone stopped ringing overnight,” he says. “Suddenly there was no bar on the island, no restaurant and a ferry service only once a day. I almost walked away [from the business] three times. Since then we have always thought the resort would reopen so we have been hanging in there, waiting, waiting, waiting.”

For 14 years, locals have waited in vain for Tower Holdings to either revive the resort or sell it. In 2012, the company won development approval for a new resort including luxury villas, shops, a marina and an extended runway. But it clashed with the Queensland government over its desire to run a casino at the resort and the project never went ahead. In 2018, Tower put the leasehold on the market and two potential buyers, from Taiwan and Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, tried to purchase it before the deals fell through.

Just when the island’s locals were giving up hope they received news in October last year that Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting had begun discussions to acquire the island’s leases. Rinehart’s company is arguing that with the 2032 Brisbane Olympics on the horizon, the redevelopment of Great Keppel would showcase Queensland as a premium, world-class tourist destination. In other words, Rinehart sees the revival of Great Keppel as a new beginning for all the state’s island resorts. “Currently, for various reasons, Great Keppel is not a showcase for Queensland,” Hancock Prospecting says in a statement. “We hope to make it better than it has ever been, with a world-class year-round beach club, sandy bars, shopping and more experiences circling around a marina modelled after successful marinas like Puerto Banús [in Spain]. Gina Rinehart is very passionate about Australia and Queensland and hopes that her vision is shared by the Queensland community.”

The bid is still being evaluated by all parties and a spokesman from Hancock refuses to comment further. Tower Holdings’ Terry Agnew did not return calls. But tourism minister Hinchliffe says building a new resort would be a win for the island and the region. “If the redevelopment plan for Great Keppel Island proceeds it would complement existing tourism operators, increase accommodation options, create new visitor experiences, deliver new construction and operational job opportunities and stimulate further investment in Central Queensland.”

For most of the island’s residents, the notion of Rinehart restoring the resort is manna from heaven, even if they squabble over the size of her plans. “It would be good for the island,” says Kelly Harris, who manages its largest tourist accommodation, the Great Keppel Island Hideaway. “The locals just want to see the place cleaned up. It’s embarrassing. Since the resort shut a lot of the facilities on the island have been let go and are in bad need of repair. The walking tracks need repairing, in fact the whole island needs a good clean-up,” he says. “You hear different views on the island about the possible sale to Gina Rinehart. Some people want the development to be really big and some want it smaller but everyone wants a clean-up of some sort.”

Well, almost everyone. Joyce Lorraway, 93, has lived on Great Keppel for 58 years and sees no place for someone like Rinehart. “This island is paradise and Gina will just ruin it,” says Lorraway outside her home on the island’s idyllic main beach. “They want to put a marina in, but what about all the glorious coral?”

For decades Lorraway fished the waters around the island for a living with her late husband Noel. She has seen the island morph from its rustic pre-resort days through the Get Wrecked party years to the era of abandonment. “Anyway, the old resort was haunted,” she says, pointing to the ruins just metres from her home. She recalls seeing the ghost, a figure that would walk through the walls of the resort and occasionally through her own house.

Nearby, Geoff Mercer is walking through the abandoned resort to meet a friend, Dennis, an artist in his 80s who has become a squatter amid the ruins of room 545, where he enjoys million-dollar views for free. On the way, Mercer shows us through the broken rooms. “Can you believe this place was once crawling with mums, dads and kids? The pools were full, the place was buzzing. Now look at it,” he says as he walks into a derelict room. “The broken doors, the old mattresses, the broken glass, I mean it’s an absolute disgrace.”

Down the hill, standing under his shop sign “Great Keppel Island Pizza, a slice of paradise”, Gerry Christie says people can’t keep putting Band-Aids on the island’s broken-down infrastructure. “The resort has been closed for 14 years now and in that time we’ve had ups and downs, we’ve had controversy, we’ve had buyers, including Chinese ones, who didn’t come through,” he says. “We have to produce our own electricity, water and deal with our sewage and for better or worse, the island has been neglected by all tiers of government for the last 50 years. I think we should all be doing backflips that Gina is interested in us.”

We find out later that Christie showed Rinehart around the island when she visited late last year with her large boat and entourage to inspect the ruins. But when I call Christie back to ask about it, it’s clear he has been muzzled. “She’s a pretty private person, she came here on a private boat last year but, um, I really can’t say anything about her,” he mutters.

A few hundred metres away, Shane Bonney, owner of general store Tropical Vibes, is playing his guitar, singing a song he wrote about his wife Dot’s narrow escape from death. “It was pretty wild,” Dot recalls as she explains how she was booked to fly from Amsterdam on Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 in July 2014 when she cancelled at the last minute. The plane was shot down over Ukraine by Russian-backed rebels, killing all on board, and for 24 hours Shane thought his wife was dead.

The Bonneys say they have a good life and while they understand a new resort would be good for the island, they are worried about its size. “I guess we want to see a resort here because the island needs updating and if Gina does the right thing by the island then it will be OK,” says Shane. “But it’s the size that is the hard question. Some people don’t want change here so you have to be careful what you say. We want to stay friends with everyone. But either way, this island is going to be all right. You’ll never stop people from coming here because it’s one of the most beautiful islands in Australia.”

Geoff Mercer also wants a smaller version of what Rinehart is offering. “I don’t want a marina and I’m not sure about a larger runway,” he says. Despite the bittersweet fortunes of Great Keppel over the years, Mercer says he can’t bring himself to leave. “I think it’s mostly been a great love relationship with this island but as I’ve got older I feel my time here has also been tinged with layers of disappointment about how the island has been treated by people. I haven’t made a lot of money like I should have. But every time I have tried to leave something has brought me back. Every time I have almost gone broke, someone has lent me money and I have managed to keep getting my businesses over the line.”

The thing about Keppel, he says, is that no matter how much it is mismanaged it will still be as beautiful tomorrow as it was yesterday. He pauses to think about what he has just said and then smiles. “Maybe that’s why I haven’t left. I feel confident about the future and I would love to be a part of a new beginning.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout