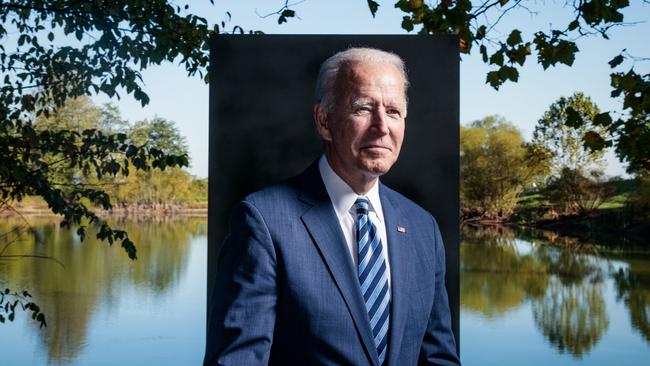

Will Joe Biden really run for a second term as US president?

With Trumpism reascendant, ambivalence about Joe Biden’s age and standing is fuelling scepticism just as the image of Kamala Harris dips even further than his.

On a Tuesday evening in April, nearly half a century after Joe Biden first publicly mused about running for president, an unsettled cross section of the Democratic Establishment assembled at Pinehurst, a golf resort in North Carolina. Inflation was at a 40-year high, Biden’s disapproval rating sat at 56 per cent, and editors at The New York Times were readying a front-page report about how his signature achievement – $1.9 trillion in coronavirus-relief spending – has “barely registered with voters”. The lobbyists, donors, staffers and elected officials were gathering for the spring policy meeting of the Democratic Governors Association, and the scheduled sessions concerned such topics as health care and diversity in governance. But between panel discussions, in the hallways and at the cocktail reception on the lawn, conversation shifted from grim – the upcoming midterms – to grimmer: the state of the party’s planning for 2024, when Biden plans to stand for re-election on the eve of his 82nd birthday.

Biden hasn’t formally announced his campaign for a second term, but in his mind there’s no question he’s running. “That’s my expectation,” he said early in his tenure. “Yes!” he told an interviewer nine months later, sighing a little performatively at having to keep repeating it. “It’s been his life,” says one of his longtime advisers. “It’s like a shark that keeps swimming. It’s how he stays alive.” Or as another top Democrat puts it, “He was told in ’16 he couldn’t cut it. He runs in ’20 and everybody rolls their eyes, and he still wins. So why in the world now would he be like, ‘You guys are right. I am old’?” And yet many of the plugged-in Democrats wandered Pinehurst not entirely persuaded, calculating contingencies: If Biden’s health turned, or if his polling truly collapsed, which of the party’s governors might step up and save them from electoral ruin – and the nightmare of a Trump comeback?

Governor Roy Cooper – the conference’s host, who had twice won North Carolina in the same years the swing state was carried by Donald Trump – was the most frequent topic of shadow-campaign chatter. Governor Phil Murphy, the New Jerseyan whose national ambitions are among Washington’s worst-kept secrets, was a close second. Towards the end of the event, phones buzzed with an alert: a memo from Bernie Sanders’ last campaign manager had been leaked to the Washington Post. “In the event of an open 2024 Democratic presidential primary, Sen. Sanders has not ruled out another run for president,” Faiz Shakir wrote to the senator’s aides and surrogates. It was the first acknowledgment that the two-time candidate is still considering his options. “So we advise that you answer any questions about 2024 with that in mind.”

Inside the White House, 530km north, a handful of Biden’s aides were monitoring Pinehurst and reading the Sanders memo with a measure of bafflement, even scorn. From their perspective, the hypothesising was absurd. Every one of the would-be candidates has consistently maintained that their own presidential prospects are moot because Biden is running with their full support. As far as Biden’s camp is concerned, there isn’t any ambiguity about 2024 at all. He has said in private that he sees himself as the only thing standing between the country and the Trumpian abyss and has instructed his aides to redouble their planning for a rematch. “People ask me with some regularity, ‘When is Biden going to come out and say what he’s going to do?’ ” an exasperated longtime Biden adviser told me recently. “And I say, ‘Well, he has!’ ”

Relatively few people outside the White House totally buy it. With Trumpism reascendant, ambivalence about Biden’s age and political standing is fuelling scepticism just as the image of his understudy, Vice-President Kamala Harris, dips even further than his. A recent analysis from the Los Angeles Times has her net approval rating at negative 11. The result is a bizarre disconnect within the Democratic Party, with two factions talking past each other. One group consists of Biden and his loyalists, who are convinced that while the ticket’s numbers are undeniably bleak, they’re historically unsurprising for a president and VP facing their first midterm and will surely bounce back. The second group comprises a broad swath of the Democratic elite and rank and file alike, who suspect that vectors of age, succession and strategy have created a dynamic with no obvious parallel in recent history. No one seriously wondered about Barack Obama’s plans to seek a second term in the spring of 2010, or Bill Clinton’s in 1994, or even Jimmy Carter’s in 1978. In the past few months, though, many of the Democratic Party’s biggest donors – even as they pledge to back Biden’s re-election in earnest – have quietly started to poke around for alternatives in 2024, partly out of a sense of responsibility just in case Biden steps aside. Several have bombarded Obama’s old associates with pleas for insight into some sort of top-secret real plan that must exist for the next presidential contest.

There is no substantial precedent for the volume of questions about Biden’s future. His inner circle’s insistence that his doldrums will pass, that there’s no cause for concern, is of little reassurance even to some close allies in the party. One person who fits this description has tried casually mapping out ways Biden could get away with avoiding a re-election bid without losing face. But as this person puts it, “The fumes from the paint in the White House are pretty strong.”

It’s not clear if anything can change the dynamic – not even the epochal shock that the Supreme Court is all but certain to overturn Roe v Wade. After the news broke Biden had an opportunity to revitalise his standing. But rather than galvanise his party around a cataclysmic moment, Biden, who has never been comfortable saying the word abortion out loud, issued a statement but didn’t up-end his schedule.

As they look towards 2024, Democrats are unified in their conception of doom but divisions remain over how to prevent it. It’s possible to read the actions of nearly a dozen Democrats as putting themselves in position to run on the off-chance that Biden doesn’t – or can’t. Only three in 10 Americans think Biden will seek a second term, according to a recent Wall Street Journal poll. That survey also revealed that even among Democrats, a group that likes and approves of Biden in general, fewer than half are sure the president is planning on round two and a third outright think he isn’t. Biden can’t discredit the findings; the data was gathered in part by the research firm led by his own pollster, John Anzalone. More troubling – because it indicates that such doubts aren’t just about transitory twitches in popularity – is that similar scepticism arose in a series of private focus groups conducted by left-leaning organisations supportive of Biden last year. And that was before his approval ratings started to approach Trumpian lows.

This untenable state of affairs – in which Biden insists he wants the job until he’s 86 but much of his party won’t listen – is only partially a by-product of his not yet officially declaring his candidacy. (He’s following the traditional timeline, in which the incumbent relaunches after the midterms in November.) It’s partly because of Biden’s own occasional hedges: with family tragedies and two brain aneurysms in his past, he has always allowed that he might step aside if his health declined or if “fate intervened”. But its origins may also be traced precisely to March 9, 2020, when Biden pitched Democratic voters on a certain vision of the future.

“Look, I view myself as a bridge,” he said that day. “Not as anything else.” He was onstage in Detroit, on an exhilarating high, less than a week after a shock Super Tuesday romp that supercharged his primary campaign and made it almost impossible for Sanders to catch up. One by one, younger competitors had dropped out and endorsed him, consolidating his power and momentum. Gesturing at Harris, Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer and New Jersey senator Cory Booker during his closing argument, he said: “There’s an entire generation of leaders you saw stand behind me. They are the future of this country.” Biden didn’t intend his remarks to be a one-term pledge but the notion had been in the air; some allies had debated the idea semi-openly in the press just a few months earlier. Regardless, this appearance in Detroit was replayed frequently and promoted enough in the ensuing months to become a symbol of Biden’s promise to defeat Trumpism and then let the country move on, ushering in a new era of leadership.

He did get Trump out of DC and away from the nuclear football. But after the immediate crisis slunk away to Palm Beach, Biden’s presidency passed from early success into torpor, dragged down by a chaotic exit from Afghanistan, sometimes shocking rises in prices, and the determination of two senators from his own party to block his grandest legislation, all while the coronavirus lingered longer than expected. It became clear that Biden’s bridge, to consider his analogy on its terms, wasn’t built to completion at the far side. For liberal and progressive voters, the cognitive dissonance has been significant. It is possible for Democrats to feel profound gratitude to Biden for vanquishing Trump and even to love some of his work as president and at the same time to retain an intense feeling of unease about a visibly ageing 79-year-old whose Republican opponents are only growing more extremist.

This might be more straightforward to process if not for the slide in Harris’s public image, which has been in some ways more startling than that of Biden’s. In 2020, Biden was clear that he chose her to join his ticket in large part because he thought she represented Democrats’ future and saw in her not just the first woman vice-president but also possibly the first woman president. Yet in Washington, that was a political lifetime ago. Harris took on a substantive but, in hindsight, politically impossible portfolio, focusing on voting rights and the roots of the Central American migrant crisis. As those issues languished, so did her office’s relations with Biden’s. Lacking Biden’s decades of experience on Capitol Hill and abroad, Harris was never going to play the role Biden did for Obama. But her approval rating is 15 points below where Biden stood at this stage in Obama’s first term and 11 below Mike Pence under Trump. Harris has never let anyone doubt she expects Biden to seek a second term, and she has made no moves to set up a contingency campaign. Yet a Politico newsletter recently pointed out that 27 surveys have tested the prospect of a Biden-free primary in the past year and Harris has led 21 of them. (The remaining six were led by Michelle Obama.) In the meantime, nothing has budged Biden’s sense that nobody but him can keep Trump out of the White House. Facing a country dubious that he will run, Biden just gets more convinced that he must.

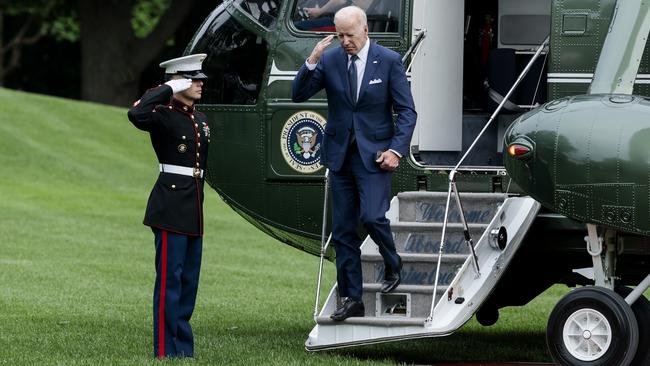

Lately, some of Biden’s associates have reminisced uncomfortably about his obvious exhaustion during the 2020 primary and expressed wariness at the prospect of another campaign. “I’m 66 and I’m f..king exhausted,” one of his longtime buddies told me recently. “I can’t even imagine being 78, 79, 80, 81, 82 and starting again. Just waking up is a chore.” Anyone who has watched Biden can see that he walks more stiffly now – as noted publicly by his White House physician late last year – and that he appears to speak more slowly at times. Biden doesn’t hide his seniority. He joked about it at the recent White House Correspondents’ Dinner, and in 2019 he told voters it was a valid concern. “There are some people who are old and decrepit at 55 and haven’t had an original thought since they turned 40. It all depends on the person,” says former California senator Barbara Boxer, a longtime Biden friend. “The best way to answer is to be yourself and show people you can do what you were elected to do.” But here again is a disconnect – this one between a cluster of those with first-hand knowledge who maintain there is no cause for concern and a larger group of outsiders who think, He’ll turn 82 the month of the election. How can there not at least be some?

The consensus of people who deal with Biden in person, from aides to journalists to senators, is that he has shown no signs of slowing down mentally and that the clips frequently circulated of his momentarily struggling to speak are nothing new – just examples of his lifelong stutter and his difficulty with teleprompters. To think anything else, the Biden faithful argue, is to fall for Republican misinformation. To take one bad-faith example, Senator Tom Cotton recently tweeted a video of Biden stumbling badly over the word “kleptocracy” during an address about Ukraine. Biden closed his eyes and tried to recover, landing on “the guys who are the kleptocracies” and laughing ruefully. They were some of the only garbled moments in a long speech, but the video gathered more than 3.4 million views within four days.

Many of Biden’s backers are taking solace in the idea that his own unpopularity is more structural than personal. “We’ve had three straight presidencies now in which 100 per cent of the other side can’t stand you, 85 per cent of your side is with you, and there are a certain number of people who are pissed off on your side so you’re stuck in the low 40s,” says one congressional representative who is close to the White House. This analysis is true enough but not necessarily sufficient to those who have been around long enough to recognise the unique peril of the moment.

Biden is sustained by his contempt for Trump and the imperative of keeping him out of office. “If Trump is alive,” one veteran adviser says, “Biden is running.” Whatever doubts his party harbours, his inner circle believes that “if it’s Trump, Democrats will circle the wagons,” in the words of a former aide. In private moments, Biden has been reflective, recently musing about his predecessor in a way that reminds his confidants of the aftermath of the 2017 neo-Nazi attack in Charlottesville – the moment Biden started to take 2020 seriously. The first question he asked his advisers was whether he could beat Trump. Then he lingered on a second one: “If I don’t run, who’s going to beat him?” He didn’t know it would remain an open question half a decade later.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout