Wildlife warrior Warren Ellis: ‘It just felt like such a great thing to do’

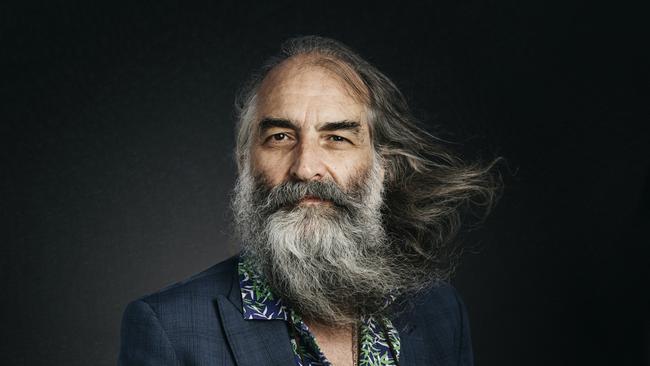

He’s an unlikely saviour for some of the world’s most mistreated animals. What made Australian muso Warren Ellis step up?

Warren Ellis’s unlikely path from Bad Seed to wildlife warrior began with a beard balm. It was March 2021, a year into pandemic lockdowns, and the musical polyglot – violinist, guitarist, pianist, long-time Nick Cave collaborator, author, and one-third of the rock group Dirty Three – was working from his home outside Paris when he got a call from an old friend, former Melbourne band-booker Lorinda Jane. She had just made a range of palm-oil-free beard products as a side-hustle to her main gig as a campaigner for the protection of orangutan habitat in Indonesia, and was looking for a brand ambassador.

Ellis, instantly recognisable for his bushranger beard, seemed the perfect fit. The two hadn’t spoken for years but her timing was excellent. The 57-year-old musician had already been raising money online for orchestras and venues struggling to survive the pandemic, but told Jane, a veteran publicist who knows an opportunity when she sees one, that he wanted to do more. “She said there was a woman she knew doing amazing work in Indonesia, and she could introduce me,” says Ellis.

If such a thing can be said of anyone, Ellis has had a good pandemic thanks to a decent internet connection and the luxury of time to feed an insatiable creative fever. He has written a book, Nina Simone’s Gum, which is nominally about the discarded chewy he scavenged from the top of the singer’s piano in a London club 22 years ago but more esoterically about the insignificant things that bind us. He’s recorded an album with Marianne Faithfull, two more with Nick Cave – they’re currently touring in the US – and, with Cave again, composed the film score for a French documentary on snow leopards. The two also star in an upcoming doco by Australian filmmaker Andrew Dominik about their friendship, This Much I Know to be True.

Less obviously, Ellis has donated his name, time and a chunk of earnings to help build a permanent sanctuary in Indonesia’s South Sumatra for rescued wildlife too profoundly handicapped or mistreated in captivity ever to be released back into the wild. “After the last couple of years it seemed increasingly important to do good; it’s kind of about the good things we choose to do,” he says of Ellis Park, a project that has done him almost as much good as the animals it harbours. “I’ve got to a point in my career where things are ticking over. I don’t care about having a big car or buying a bigger house. Being able to do this just felt like such a great thing to do.”

Within weeks of her first call, Lorinda Jane had set up a three-way Zoom meeting with Ellis and Femke den Haas, a 44-year-old veterinary paramedic who’s been a driving force for more than two decades in the fight to end wildlife smuggling and animal cruelty in Indonesia. They talked for two hours, though “within about 30 seconds I was blown away by Femke”, says Ellis. “She told me what they needed was a place for animals that are so badly mutilated they can’t be released back to nature, which struck me as a really beautiful thing to engage in. I wanted to help, but had to check first with my accountant that I wasn’t overreaching. At that stage all touring had shut down so certain revenues I would have had were closed down.” A fortnight later, Ellis, Lorinda and den Haas had hatched a plan.

Each morning at Ellis Park the “doo-wop” song of its resident Bornean gibbon, Trinity, echoes through the small, nurtured South Sumatran jungle where native palms and fruit trees bear the names of distant, music-loving benefactors. There’s a Warren Ellis durian tree, a Lorinda Jane sapota tree and countless more whose generosity is memorialised on squat green signs sprouting from the ground.

The face of Ellis Park, however, is not a hirsute musician but a double-amputee macaque called Rina who makes cooing noises as she eats rambutan in her new home, and smacks her lips at newcomers in chatty curiosity. She can no longer swing but uses the full length of her enclosure to run frantically after her “surrogate child” Dede, an infant macaque whose celebrity Indonesian owner would dress her up and exploit her for YouTube content until being publicly shamed into giving her up.

Rina’s limbs could not be saved after she was found chained to a pole, hands gnawed open to bone and tendons, during a raid on the house of an illegal wildlife trader by Indonesian police and the Jakarta Animal Aid Network. It was a shocking sight, even for den Haas, who co-founded JAAN in 2008 and whose tireless animal rescue and advocacy work has helped shift public attitudes towards Indonesia’s rich and diverse wildlife.

“She was under so much stress. Her wounds were being treated with gasoline. It was like a horror movie,” den Haas recalls. “We first had to amputate one arm, and tried to save the other but we couldn’t. Amputating the second was such a difficult decision because even with one arm she still could have been introduced back into the wild. Rina has been so abused, she doesn’t accept many others… so it was a huge relief when she accepted Dede.” The younger macaque will one day be released, she adds.

The illegal wildlife trade is the world’s fourth-largest contraband market and a good deal of it comes from Southeast Asia, where animal smuggling is worth an estimated $US2.5 billion a year. Indonesia alone, with one of the world’s highest numbers of endemic species, accounts for up to $US1 billion of that market. Since 2002, den Haas has helped establish sanctuaries across Indonesia that provide temporary homes for thousands of animals – orangutans, monkeys, gibbons, civet cats, sun bears, endangered birds, even crocodiles – rescued from wildlife smugglers and traders or the squalid misery of a backyard cage.

At her own Sumatra Wildlife Centre, which Ellis Park now adjoins, a group of dedicated vets, animal paramedics and volunteers nurture those animals back to health and prepare them for release back into the wild. Finding safe release sites is hard enough, given the continued threat from poachers and habitat destruction. But the question of what to do with rescued animals that have spent their lives in captivity, or are so damaged by years of mistreatment that they can never be released, has been a constant problem.

For years den Haas dreamt of providing them with a “forever home”. Bitter experience has taught her zoos are largely uninterested. “They only want perfect specimens,” she says. But Ellis Park, she says, is a dream come true.

Warren Ellis dug deep into his own funds to buy the land for the park, and worked hard to build a community of supporters among his own friends and followers. His commitment has surprised himself almost as much as it has den Haas. Neither can quite believe how quickly Ellis Park has come to fruition. It already has its own veterinary clinic and an antique teak joglo (traditional Javanese house) where den Haas plans to run wildlife education classes for local kids. Both were co-funded by Ellis and Nick Cave. “I’m a guy who’s made music for 30 years,’’ Ellis says. “It doesn’t mean everyone who’s interested in what I do is going to be interested in this, but it does mean I have a different audience, and when I started talking publicly about this the response was amazing.”

Femke den Haas, a blonde and tattooed Dutchwoman, is a lean streak of practical energy who never seems to tire as she juggles multiple tasks, but even she admits she has been spread thin in recent years fighting animal welfare battles on multiple fronts. It was JAAN that successfully fought to outlaw Indonesia’s dancing monkey industry, and is still fighting to end the dog meat trade there. She runs a raptor and eagle rehabilitation and release program in the Thousand Island chain off Jakarta, dancing monkey rescue and rehabilitation in Bandung, sea turtle protection in Flores and the world’s first rehabilitation program for performing dolphins – they were rescued from a Bali hotel where they’d been kept in a chlorinated pool for guests’ entertainment.

JAAN’s focus is on “solutions-based protection”, and working with Indonesian authorities to help find those solutions has earned it the respect and trust it needs to push for more reform. “We don’t just confiscate the animals, we take responsibility for them, so the government trusts us with the big raids,” says den Haas of the operations that often involve JAAN volunteers posing as buyers to animal traders before launching rescue bids.

As her reputation has grown, so has her workload. It has been a constant battle securing funds to care for the animals in JAAN’s care, rehabilitate those that can be released, and still accommodate the steady stream of new rescued wildlife sent to her for care. When Ellis told den Haas in April last year he could help bankroll a sanctuary, he says “she just sat there and tears rolled down her face”. By late June he and Lorinda Jane had designed a website and a logo. From their respective bases in Australia, France and Indonesia, they then launched the Ellis Park Instagram page with the help of high-profile friends including Nick Cave, Cat Power and Flea from the Red Hot Chilli Peppers. Meanwhile, Jane has steered a financing effort that has so far raised almost $200,000 to establish and run the park.

Behind every one of the Ellis Park residents is a story of grotesque exploitation and cruelty. Trinity, the one-armed gibbon, was rescued from a filthy cage in suburban Surabaya where she’d been kept for 20 years. Video of her rescue shows a distressed animal with a foot dangling sickeningly from a broken leg that had never been treated. Gibbons are protected in Indonesia and it’s illegal to keep them as pets, though that hasn’t stopped the trade. It’s not easy to hide a gibbon because they make a lot of noise, but if they’re unhappy they don’t sing, says den Haas.

Indonesia has good orangutan and gibbon rehabilitation programs, but because Trinity is handicapped she’s not a candidate and will need sanctuary for life. So too will Koja, an elderly macaque with spinal problems from spending 22 years hunched inside a tiny cage at a roadside food stall in Jakarta; den Haas rescued her in 2019 after a tip-off, and in late January carried her carefully from her temporary pen at the Sumatra Wildlife Centre to her new Ellis Park home, where the goldfish pond and view of the fruit and vegetable garden were an immediate hit.

Koja will eventually need a companion and den Haas hopes an elderly macaque called Baron, a rescued pet that suffered brain damage from beatings, might fit the bill. In the meantime, the gentle primate seems to crave human touch; she repeatedly reaches out to hold my hand, at one stage cradling mine in both of hers and softly pinching my skin as though trying to understand its hairlessness.

The park will soon house at least one young sun bear, Balou, who was poached from Sumatra’s jungles as a cub and smuggled to Bali where she is now stuck in a transit rescue station. A group of brahminy kites, their wings cut to the bone by wildlife traders so they can never fly, will also move in next month.

A silver lining of the pandemic was a brief respite from the relentless trade in Indonesian wildlife when the government closed the harbour connecting Sumatra and Java and restricted movement between islands. But as those restrictions have relaxed, the trade has resumed and traders are now racing to fill back-orders for thousands of exotic birds, reptiles and mammals.

The distant lights of Java beckon over the Sunda Strait as traffic rumbles into South Sumatra’s Bakauheni harbour for the rough, rainy-season ferry ride to Indonesia’s largest and most populous island. Inside JAAN’s animal rescue ambulance, parked near the harbour entrance, a team of wildlife detection dogs whine and shuffle restlessly inside their crates. Bakauheni harbour is the main gateway for the trafficking of some of the world’s most endangered and exotic wildlife, and the dogs – specially trained by the Scent Imprint for Dogs centre in Holland – are eager to get started.

In recent months Bailey, a cocker spaniel that leads the canine unit, has sniffed out thousands of birds, dozens of macaques, plus snakes, tortoises and two baby orangutans. Most have ended up, at least temporarily, at JAAN’s wildlife sanctuary.

Handlers release the dogs from their crates and lead them from vehicle to vehicle as local police and forestry officers smooth their path. The late-night operations would not be possible without official co-operation, but it comes at a price. By the time this one begins, den Haas has spent hours co-ordinating the capture of an “ex-pet monkey” that has breached the Bali governor’s residence. The urgency with which the matter is expected to be handled is particularly notable given the same governor was only weeks ago uploading photos to social media of his new pet baby gibbon. The photos went viral, triggering public outrage and forcing him to hand the animal over for release. (The gibbon was a gift from the local House of Representatives.)

While Indonesia has taken serious strides to crack down on the illegal wildlife trade, a thornier issue is the legal wildlife market in which millions of animals are traded each year. Den Haas chose the location for the Sumatra Wildlife Centre and Ellis Park for its proximity to the harbour where so much wildlife is smuggled. The sanctuary is now nursing dozens of infant pig-tailed and long-tailed macaques that were snatched from their mothers.

It takes only moments for an experienced poacher to snatch an infant monkey from its mother, but years for den Haas’s team to prepare it for release, including introducing surrogate monkey mothers through which they can form family units. Still, the Sumatra Wildlife Centre works miracles on its shoestring budget. Volunteers wearing band-style “Queen of Ellis Park” T-shirts all muck in with little sense of hierarchy. Animals are fed, enclosures cleaned. The beginnings of a sun bear pool are being dug in the middle of Ellis Park. But den Haas is working at a different level again. Five macaques must be microchipped ahead of their release this month and it takes her and two other volunteers almost an hour of scaling the enclosure to catch them.

The defiant primates are finally marched over to Ellis Park’s clinic, their arms held behind their backs like little felons. “Our first patients in the clinic!” den Haas grins as she tranquillises them on a sterile table. “It’s so exciting to have a fully equipped place.”

If he stops to think about it, Warren Ellis admits the idea of supporting a “forever home” for disabled wildlife is a bit daunting. “There was a moment where I thought, ‘Oh God, what am I doing?’” he says. “But seeing what Femke is doing, to see what you can do with a life, is so inspiring. But I can’t stress enough, since this has happened I can’t imagine my life without the park. It has opened up something in me that wasn’t there.”

While Ellis has come late to wildlife protection, Femke den Haas has been at it since she left school at 16 to volunteer in an orangutan rehabilitation camp in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo). Years on, with an Indonesian husband and son, and animals that depend on her, the country is home and Ellis Park “the one place we can really call ours”. By any measure it has been a remarkable collaboration with Ellis – all the more so considering the two have never met in person and the Australian has never been to the sanctuary, let alone to Indonesia.

Some days he dreams of sitting under a tree in Ellis Park, peeling bananas for the residents. The spirit of the sanctuary goes to “the goodness in people and our potential to do amazing things”, he says. “It’s like a piece of music. The community gets underneath it and people carry it with love and care. That’s what happened with the park. We put it out there, people saw it for what it is and rallied around it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout