Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards: Justin Gilligan’s image

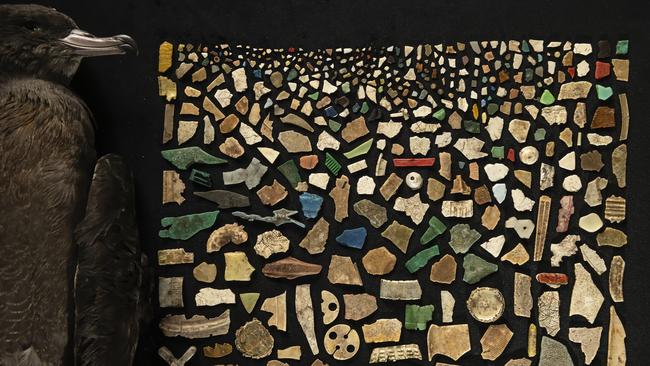

The 403 fragments of plastic in this mosaic were found in the digestive tract of a young seabird on Lord Howe Island. It’s a grim new record, researchers say.

Before we get to the sad bit, there’ll be a fun bit. But first, the amazing bit: as soon as a flesh-footed shearwater chick can fly, at the age of 90 days or so, it will launch itself from a vertiginous green slope on Lord Howe Island and head north – and its feet won’t touch solid ground again for five years. It’ll spend all that time in the Sea of Japan, or the Bering Sea off Alaska, living on the ocean. When it finally reaches sexual maturity, aged five, it will return to Lord Howe (how it finds its way back, nobody knows – “It’s a big mystery,” says researcher Dr Jennifer Lavers) during the summer breeding season to find a mate. Flesh-footed shearwaters pair up for life, and typically live for 30 years, each summer returning from those northern hemisphere waters to the exact same nesting spot on Lord Howe Island, where they raise a single chick together. Aren’t they amazing?

Now the fun bit. They’re known colloquially as muttonbirds and their party trick is crash landings. When, as adults, they return to the nest at dusk after foraging in the ocean all day, they’ll suddenly tuck their wings mid-flight and drop to the ground, crashing through the canopy and landing with a thud. It’s a softish landing, at least, given they nest in deep burrows in sandy soils, but it’s a bizarre sight. “They plummet to the ground like spaceships,” says Lavers, adding with a laugh: “You wouldn’t want to be hit by one.”

Now, alas, for the sad bit: Justin Gilligan’s image A Diet of Deadly Plastic, which has won a gong in the international Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards, depicts the 403 pieces of plastic found in the digestive tract of a single chick; it died a few days before it would have fledged. Lavers, a researcher for Adrift Lab, which studies the impact of plastics in our oceans, helped to create this grim mosaic to make a point: “403 pieces from one bird is a new record,” she says. Plastic scars the gut of birds, and can lead to starvation. The very saddest part? All of these bits of junk were fed to the chick by its devoted parents, which took the stuff to be food.

“It feels overwhelming sometimes to bear witness to this,” says Lavers. We’re all to blame, ultimately; who doesn’t use plastic? But we can do something about it – starting with the low-hanging fruit, she says. “Try to use less.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout