Why WA premier Mark McGowan is riding high

As a politician, he never set the world on fire. But suddenly WA’s premier is getting rock star treatment. What happened?

Mark McGowan was lying back, blood draining from a tube in his arm, when the attendant at the blood donation centre approached. She handed him a card that said: “Just wanted to take a moment to recognise your leadership in one of the most challenging and unprecedented periods in our lifetimes. We watched your no-nonsense approach and commonsense solutions in awe and I am so proud to be living in this state right now.” Western Australia’s premier had just entered unusual territory for a politician.

The praise has taken many forms, from social media beer toasts and a “Thank you to Mark” driveway vigil of 3000 Perthites. (“I don’t think that is necessary,” McGowan said at the time. “Lots of people are working a lot harder than me. Pretty sure my wife and kids won’t be out there clapping.”) On days when he’s stood in his seaside electorate of Rockingham giving COVID-19 updates, the live broadcast has been punctuated by a passing car driver honking their horn or someone shouting “F..king love you, buddy!” A Newspoll in late April gave McGowan an 89 per cent approval rating, the highest of all state premiers.

Premiers riding wave of popularity

But the truest picture of McGowan’s status in the eyes of his people, before and after COVID-19, was summed up by one online admirer: “Must admit, I didn’t even know who he was before, but now 100 per cent he has my vote.” It’s almost distasteful to say that a pandemic has been the making of Mark McGowan, but it’s probably true. He had been a hard-working but unremarkable MP for 20 years before becoming premier three years ago, the longest apprenticeship of almost any of the state’s 30 premiers. Most Australians east of the rabbit-proof fence would have struggled to name him 12 weeks ago; now he’s rated the nation’s best political performer. From Mark McWho to McGowan the COVID Slayer.

Close political admirers such as former WA premier Geoff Gallop think he should one day offer himself to federal politics but McGowan, 52, says he’s hardly lying awake yearning for Canberra. But then, he’s had life-and-death decisions to mull over during many sleepless nights that have only eased since the state’s daily COVID-19 case count clicked over to a series of zeros. “The first few weeks were very stressful,” admits McGowan, who seems strikingly relaxed as he sits in a socially distant armchair in his fifth-floor office overlooking Perth’s Kings Park. “When you’re making decisions that close down people’s businesses, you walk through the shops and people are putting signs in their window saying, ‘We’re closing’, when there are huge spikes in infection and you’re worried people are going to die, it’s stressful.”

On January 20, five days before Australia registered its first coronavirus infection, McGowan flew to Coffs Harbour in NSW to surprise his father Dennis for his 80th birthday. He speaks to his parents a couple of times a week – “the kindest, most loving parents you could ever want”. That they haven’t seen him since January is entirely the fault of coronavirus and their own son; McGowan cut Western Australia off from the rest of the nation by closing its borders on April 5 and says he has no intention of lifting them soon.

“Mum and dad are in the ‘at risk’ category and they are very understanding of the rules,” he says. So too, remarkably, were the state’s 2.7 million constituents, who found themselves locked within one of 13 zones when police erected intrastate borders. McGowan presided over draconian state laws that stopped anyone in Perth heading to, say, the Kimberley, Pilbara or Goldfields.

Intrastate borders have now been eased but McGowan insists the “hard” border “will be the last thing to come down” while there’s community spread of the virus in NSW and Victoria: “I think people understand that.” They’ve certainly been more understanding than the constituents of Queensland, who have been vocally opposed to premier Annastacia Palaszczuk’s similar stance. Clive Palmer, who sought entry to Western Australia, has lodged documents with the High Court arguing McGowan’s ongoing border closure is unconstitutional; McGowan wishes him luck.

McGowan’s only exemption has been to the Easter bunny. In a wildly popular social media appearance, he reassured children that he had signed “a special eggs-emption” to allow the Easter bunny to cross borders and deliver chocolate eggs. (The idea, he admits, came from his office staff.) He adopted a more sarcastic tone last month when NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian urged him to open up WA’s borders. “NSW had the Ruby Princess – I mean, seriously?” he said scornfully. “And they are trying to give us advice on our borders, seriously? Do you think I should listen to them? I’m not listening to them.”

It was cruise ships that caused McGowan sleepless nights, but paradoxically it was the cruise ship fiasco that enhanced his reputation. On March 23, an ashen-faced McGowan announced that the cruise ship Magnifica was headed for Fremantle and reportedly had 250 infected passengers on board. A single ship appeared likely to fill every bed in Perth’s acute hospital wards.

The ship’s report turned out to be wrong, but McGowan’s shock was palpable; meanwhile, other cruise ships were heading to the state’s ports. Like other premiers, he was already dealing with sick passengers from the Ruby Princess; they had flown into WA after all 2700 passengers were allowed to disembark in Sydney on March 19. McGowan ensured that wouldn’t happen in WA. “There are no circumstances where we will allow passengers or crew to wander the streets in our state,” he said. On March 24 he announced hotels and Rottnest Island off Perth would be turned into enforced isolation camps for thousands of returning cruise ship and international air travellers.

The border controls were a direct consequence of that cruise ship shock – and McGowan’s government was unrepentant from then on. But he could also be collegial in tone, praising Scott Morrison for the national cabinet meetings between premiers and territory leaders that McGowan believes have worked far better than COAG meetings. “In the COVID era, you’ve got to act as a nation,” he says. “Look at the United States – they’ve been a basket case. Their president is encouraging armed thugs to go into parliaments. Australia has been a shining light for the world.”

McGowan is fiercely proud of his adopted state, but until now he has not indulged its long-held separatist spirit. He can claim to be both “one of us” and an outsider; he’s the state’s first premier in almost 70 years – since Bert Hawke, Bob’s uncle – to have been born outside Western Australia. His parents, Mary and Dennis, met in Broken Hill, outback NSW. The wool classer married the primary school teacher, and when Mary was pregnant with the first of their two sons, they moved to Newcastle, where Mark was born in 1967. Dennis became a storeman at the steelworks, then bought a milk run, a grass-laying business and later a squash centre further north at Casino. Then came a move to Coffs Harbour, where McGowan’s parents and his brother Michael still live.

He played squash at his father’s centre. “I went to the national squash titles when I was 15. I got beaten,” McGowan has said. “I knew what I was good at: history, writing, language and geography. So, at 15, I worked out, ‘What can I do with what I’m good at?’” After an education in government schools, he moved to Brisbane at 17 to study law and arts at the University of Queensland. He worked hard after realising his private school peers “with tutors” were ahead of him academically.

He joined the Labor Party but only attended a rally or two against Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen. “They were funny times… I remember sitting in the refectory one day and the police marched through and ripped a condom vending machine out of the wall,” he says. “The next day some students came running past with a ‘Bjelke-Petersen House”’ sign they’d ripped off the National Party headquarters in retaliation. I joined the Labor Party on the basis I didn’t like Joh and I liked Bob Hawke. And my dad was a Labor supporter who believed in decency and fairness.”

With his law degree completed, McGowan panicked that life in Brisbane “was all mapped out in front of me”. His bid to become an Air Force pilot ended with a failed eye test, but he was accepted into the Australian Navy as a legal officer. In early 1991, aged 23, he drove his 1988 Corolla hatchback across the Nullarbor for a two-year posting at Garden Island Navy base at Rockingham, south of Perth.

He’d never heard of Rockingham, knew no one, and his friends had told him Perth was small, boring and far away. “I got here and loved it – I had a big group of mates and had a great time.” A few sea deployments, including time in the Pacific on a training ship, satisfied his taste for adventure. Then came “the most dramatic event of my life”. Driving with a Navy colleague on a wet evening in 1995, he witnessed an accident. “Two cars in front of us had a head-on collision. One blew up. We pulled over and the guy in one vehicle was unconscious. The car was on fire, so I had to get in, unhook his seat belt, and get him through a side window.” The bravery award from governor-general Sir William Deane that McGowan keeps in his office has a more dramatic description than his matter-of-fact account. “Without regard for his own safety, Lieutenant McGowan untangled the man’s legs as the fire engulfed the whole interior of the car. For his actions, (he) is commended for brave conduct.”

Yet McGowan was no career soldier. After only seven years, and still in his late 20s, he was itching to run for public office. A local Labor MP recommended local government as a first step, so McGowan stood successfully for Rockingham council and was elected deputy mayor in 1995. Meanwhile, he was working hard within Labor Party ranks. He hoped others would recognise the ambition of a wool classer’s son to represent Rockingham, a working-class electorate where tradesmen, FIFO workers, navy families and retirees predominate. “Mark was seen as an articulate rising star,” says McGowan’s health minister Roger Cook, an organiser for the Left when they supported his preselection for Rockingham. “He was identified pretty early by Kim Beazley as an obvious choice for the seat.”

But stepping up into state politics proved hard. As the outsider, McGowan noticed that Perth produced “blue blood” political dynasties, from Labor’s Beazley and Dawkins families to the state’s popular Liberal premier Richard Court, son of former premier Sir Charles. “When you didn’t go to UWA, you didn’t grow up in the western suburbs and … you didn’t have that background, you are coming from behind,” McGowan once observed. “It takes a long time to break through that.”

McGowan’s preselection for the seat of Rockingham in April 1996 came at an all-time low for Labor, a month after John Howard’s historic electoral victory against Keating. In December, Richard Court called an early state election and romped back, leaving Labor under Geoff Gallop with its lowest share of the primary vote since 1901. Two months before the election, McGowan resigned from the Navy. “The seat was in danger, so I had doorknocked every hour I wasn’t at work,” he explains. He was helped by his fiancee (now wife) Sarah Miller; they had met while he was scrutineering federal ballot papers and she was counting them. “Blonde and beautiful,” he says, smiling. “I ended up asking her out.”

On December 14, 1996, his political career began as the new member for Rockingham and then came the long waiting game; when Labor eventually won office in 2001 he was bitterly disappointed that Gallop didn’t give him a ministry. His ambition earned him the nickname “Sneakers”; colleagues joked that his shoes were the only part of him that remained visible when he was sucking up to whoever was leading state Labor. “I was a bit too ambitious too early on,” McGowan later observed about himself, “and I think people saw it. You have to bide your time in political life; it’s a marathon, not a sprint.”

That marathon lasted nearly 20 years, through five seat contests, his rise to Opposition leader in 2012 and defeat in the polls a year later to Liberal premier Colin Barnett. A short-lived leadership challenge by former federal Labor minister Stephen Smith in 2016 suggested there were still a few who doubted McGowan could win the 2017 election.

In fact, he took his party to a landslide victory, doubling the number of Labor seats. Victory was sweet, “but it was daunting – the Liberals left us with a legacy of debt and deficits, from zero debt to 40 billion in eight years.” McGowan says he slashed government spending, from growth of six per cent under the Liberals to 1.5 per cent, followed by an iron-fisted clamp on wages. He cites as his achievements upgrades for the state from credit agencies, and an increased share of GST that three previous premiers had failed to achieve. He credits that success in part to federal Liberal counterparts Malcolm Turnbull, Mathias Cormann and Scott Morrison. “They were good, and that’s helped us get finances under control… Before Covid-19 came along, we were the only state government reducing debt, and we were heading down to around 30 billion because we did difficult things. If we hadn’t done that, the state would now be in a catastrophic position. Now, our income has collapsed and our debt load will have to grow again.” Treasurer Ben Wyatt predicts the state’s economy will shrink by more than three per cent before returning to growth by 2022. Other pundits say WA’s downward spiral will be double that.

During the 2017 election, a picture of McGowan in his military uniform appeared on his campaign posters – and was quickly removed when the Defence Department pointed out longstanding rules against co-opting the military into political causes. McGowan, a reservist with an interest in military history, refused to apologise, saying his service had equipped him for leadership. Indeed, his military training has widely been seen as a source of his swift strategy against the pandemic.

Yet the fact is that McGowan’s approach was little different from Scott Morrison’s – consult widely, listen to the experts, and act fast. “When restrictions on travel from China commenced, the Premier personally engaged my peers and me in the resource sector to understand the potential impacts for domestic gas and exports of LNG and other commodities from WA ports,” says Al Williams, Chevron Australia’s managing director.

Chamber of Minerals and Energy CEO Paul Everingham was at the meeting. “He got me and a bunch of mining executives around the table and he was saying, ‘How’s this going to impact you?’ We were all saying to him, ‘Oh, we don’t think it’s a big deal’. How wrong we were.” It became the second of McGowan’s urgent problems after cruise ships: mines dependent on thousands of FIFO workers needed to stay operating or royalties of $17 million a day would stop.

Says Everingham: “The Premier said, ‘Get all the essential fly-in fly-out people you need from interstate before we have a hard border in 10 days’ time’. We did that, and there are 5000-6000 people in hotels, homes and other places across the Pilbara, the Goldfields, in Perth. I know the Prime Minister and Treasurer were very pleased the Premier was so keen to keep mining operating. But the initiative was his.”

McGowan says this account is accurate. “But I’m not Nostradamus and lots of other people realised it.” He insists he also held round tables with health, tourism and other sectors. “Nationally, people were saying we should close everything down like New Zealand did. But we said, ‘No, we’re not doing that’. We kept building and construction and mining, gas and our big box stores open.”

McGowan has long complained that the rest of the country doesn’t “get” Western Australia and its economic contribution to the nation. “This state carries the nation as far as exports – we provide huge amounts of money that flows into Federal Treasury. Every other state is a net importer but Western Australia is a net exporter. I have a greater understanding than anybody that they don’t think about us and they don’t appreciate us.”

Eastern states ride roughshod over WA again

Premiers attending past meetings of the Council of Australian Governments must have tired of hearing McGowan utter those sentiments. But now he says he is listened to in the national cabinet process that Morrison initiated and says will replace COAG. “I could talk for hours about the national cabinet,” McGowan enthuses. “It’s a thousand times better [than COAG]. It’s nimble, it’s not stage-managed, you actually talk for real about issues. It elevates the states and gives us a greater say nationally.”

He and Morrison get on well. “He’s got a great work ethic and he’s very patient,” says McGowan, who picked up the phone to the PM recently to offer him help in repairing trade relations with China. McGowan won’t say a word against China. He publicly endorsed media mogul Kerry Stokes (to whom he speaks regularly) when Stokes used the front page of his newspaper The West Australian to urge Morrison’s government not to “cut off their nose to spite their face” in its dealings with the state’s major trading partner.

China town: Coronavirus reveals true power players in the West

“We need customers, whether it’s Japan, Korea or China,” explains McGowan. “If we don’t have trading partners, our national income will die, we’ll have mass unemployment and mass reductions in wages. That’s why we need to repair those relationships.” As for his relationships with WA’s highly influential business figures, including Stokes and mining magnate Andrew Forrest, “you try to get on with people who invest billions and create tens of thousands of jobs, because they are important to the future of the state.” He adds: “I’m not a confrontational person. If you want to get outcomes, you’ve got to work with people to get what you want. If you’re hostile, you won’t.”

Yet McGowan is clearly as much campaign leader as Covid warrior as he approaches a March 2021 state election. (Opposition leader Liza Harvey complains he called her only twice during the entire lockdown period, despite demanding that her party back every Covid-19 emergency bill.) He’ll reveal more of himself this time round, having learnt that a display of humour helps. Recently, he was asked in a press conference if a jogger eating a kebab in public broke social isolation rules, and he dissolved in a fit of giggles while attempting to answer. The clip went viral.

In Rockingham’s Pink Duck Bar & Bistro, under a sign saying “Welcome back”, McGowan is pouring a beer for the cameras. He’s lifted WA’s cafe and restaurant shutdown, and is quick to tell reporters he has lifted most restrictions faster than other states. Two weekends later, he’s at a Swan Valley winery announcing the end of travel bans within the state and urging people to take a holiday at home “to get our economy going again”.

That day a local newspaper poll has given him another 89 per cent approval rating for keeping the “hard” borders shut. McGowan knows he’s on a winner with his own constituency, but if he holds out for too long will he be judged by the rest of Australia as too parochial, even separatist? “There is a strong vein of independence in WA,” he responds, “and people have felt for a long period of time that our state has received a raw deal and has been ignored at a national level... I think people quite like us giving a bit back to them.”

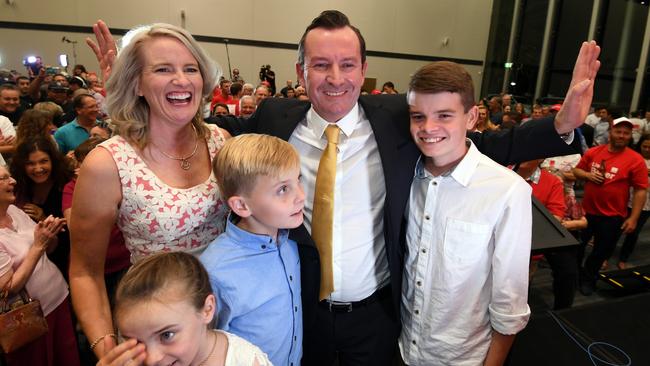

Beer-pouring over, McGowan heads out of the Pink Duck to spend a few Sunday hours with Sarah and their children Samuel, 16, Alexander, 15, and Amelia, 11. “I’ve been home more nights recently than in 23 years,” he says of the upside of cancelled events in the Covid lockdown.

Pink Duck proprietor Mark Pink says he’ll be holding no grudges against his local MP for closing him down and costing him more than $150,000 in lost income and expenses. Will McGowan get his vote? Pink looks at the retreating figure and answers obliquely: “Well, he’d have to do something seriously wrong to lose, wouldn’t he?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout