University educated, environmentally aware Pat Cummins is a man for the new age

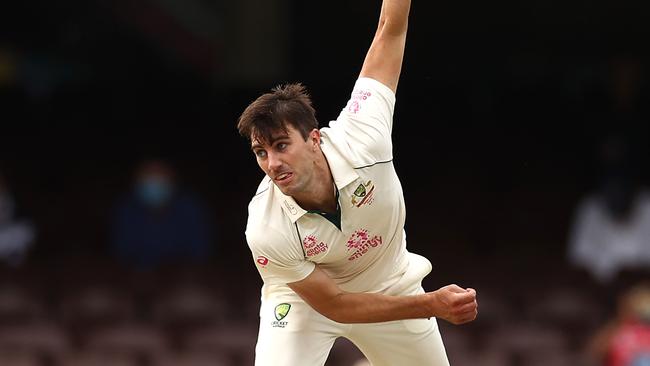

Fast bowlers are the tradesmen of the game rarely permitted to head office, but the university educated, environmentally aware Cummins is a man for the new age.

There’s every expectation that when England leaves us after the Ashes this summer, heads will nod in agreement around the board table at Cricket Australia and they’ll crown Patrick James Cummins as the 47th captain of the Test team. Australian cricket’s most marketable male is already the face of the team and jeez he’d look good in that captain’s jacket. The blue eyes, the handsome face, the beaming smile is the one every sponsor wants in their campaign. Power companies, shaving brands, clothing lines, energy drinks. The squeaky-clean image helps too. Here’s cricket’s cleanskin. No sledging, no arguing, no anger, no love-gone-wrong, no dust-ups, no bust-ups, just a business degree, a vision and the singular fact that he is the best fast bowler in Test cricket.

Fast bowlers are the tradesmen of the game rarely permitted to head office. Their hobnailed boots tear the carpet, their sweat rots the Chesterfields. It’s the tradesman’s entrance for this mob, dating back to the day they were the professionals who came up from the pit to do the hard work while the gentlemen amateurs breathed a more rarefied air in a separate change room. They ride, literally, at the back of the team bus, do the grunt work. You have to go all the way back to Ray Lindwall, who captained Australia for one solitary Test match during a personnel crisis in India in the mid-1950s, to find the last time hobnailed bowler’s boots were left outside the captain’s suite. Cummins finds himself here because Tim Paine is expected to retire from Test cricket and the captaincy after the Ashes. His predecessor Steve Smith has indicated a desire to return to the job taken from him following the sandpaper scandal but Cummins is the favoured candidate.

In every respect Cummins, 28, the current vice-captain, is the new-age cricketer. University educated, environmentally concerned, well read and well versed in the etiquettes of life as it now presents itself. He has a passion for Indigenous history and a keen interest in the possibilities of non-fungible tokens – watch that space. He is driving cricket to go green from its grass roots with a developing plan to make every club solar-powered. He drops the word “ideation” in interviews and can guide you to cryptocurrencies with the smallest carbon footprint. His first major investment is MAWDE, a local sustainable fashion brand.

Oh, and he can bowl. Boy can he bowl. Cheteshwar Pujara, the impeccable Indian batter, described a delivery in Sydney last summer as one of the best he has faced. “Unplayable,” he said. “We are trying our best, but sometimes Pat Cummins has a better idea”. The one to Joe Root late on the fourth day at Old Trafford could one day be doing the rounds as a NFT; until then you will find its anniversary celebrated on social media.

In 2020 the ICC named Cummins Test Cricketer of the Year. He took his 150th wicket in his 31st Test, the same as his mentor Dennis Lillee, but bowled fewer balls to reach the mark.

And then there’s the money, coarse as that is. The highest paid cricketer in Australia, he received a $3.2m bid (the highest recorded) at the 2021 Indian Premier League auction on top of his $2m-plus local contract. Both no doubt helped to pay for the $9.5m home he recently purchased with partner Becky Boston (now also inhabited by their newborn) and the Southern Highlands farm where he likes to invest in a little DIY.

Cummins opted to give up half the IPL payday to be on hand for the birth of their child. It was a decision so obvious he didn’t have to discuss it with anybody, including Becky. Being there was non-negotiable but he recognises the privilege involved. “I’m lucky that I am able to make that decision but for others that’s a lot harder, they’re life-changing decisions you are asking people who might be just in their late teens or early 20s to make,” Cummins tells The Weekend Australian Magazine in one of a number of conversations, the first of which was held at Sydney’s Mona Vale Golf Club where he was filming a documentary for Indian television.

Jimmy Barnes once observed that his brother-in-law Diesel was “a brilliant guitarist, a great singer, a better songwriter and good-looking”. The Cold Chisel front man said he was not sure whether he wanted to “f..k him or fight him”. Cummins’ contemporaries say something similar, if not in such rock’n’roll terms.

NSW quick Harry Conway is of the old crazy-eyes school of fast bowlers. Some years back Cummins offered him a room in his Sydney house to save him from a long commute into town. As such Conway has seen Cummins on and off the field, at his most unguarded, but he has never seen him anything other than measured, thoughtful and considerate. “There’s genuinely no dirt on the bloke, it is incredible,” he says. “Phenomenal. It is 100 per cent authenticity all the time, I’ve never seen him in a bad mood, I’ve never seen him blow up at anyone, I’ve never seen him unhappy. It is bizarre. The humility – given he is the number one fast bowler in the world – is incredible.”

Described by one cricket official as “the poster child” of athleticism, Cummins is, however, not without imperfection.

The Cummins family is large by today’s standards, close by any standard and from all reports mild-mannered and respectful, but when Pat was four their peaceful existence was disrupted by screams and a scene that brought a David Lynch touch to the semi suburban setting. Things were frantic inside the lower Blue Mountains home where Peter and Maria Cummins were raising their five delightful children. An ambulance winding its way towards the scene added to the drama. Laura, Pat’s eight-year-old sister, was in the bathroom almost as upset as Pat, who was just four at the time. The end of his middle finger was on the floor, separated like a skink’s tail from the rest of the digit.

“A family friend had picked me up from preschool and she gave me five lollipops; one for me and one for each of my brothers and sisters to share around,” Cummins says. Anyone else might have pocketed them and if he had it may have avoided injury. Instead, the excited preschooler ran into the house and began distributing them: one for each of his two older brothers and one for the younger sister, but Laura was in the bathroom. The little boy cracked the door open and poked the lollipop through to let his sister see what he had for her. Laura saw the door opening and launched herself at it to slam it shut again.

“I remember quite vividly the moment when my finger came off,” Cummins continues. “I was running around and there was all this drama and then I was rushed in an ambulance to hospital. Other than that I don’t remember it playing any other part in my childhood.” They couldn’t reattach the finger at the hospital and Cummins can remember that his parents had some immediate concerns. “Mum said she was worried that none of the girls would want to hold my hand when we lined up at school. Meanwhile, Dad was in the emergency room tossing a remote control up and down. When Mum asked him what he was doing he said he was making sure the kid could still bowl a cricket ball. They both had their priorities sorted.”

Neither needed to have worried too much. Cummins could still get the shortened finger along the right of the seam – even if it was unnaturally shorter than the index finger. And with those eyes, that smile and the chiselled good looks, girls were going to want to focus on the positives. With one girl in particular the injury proved something of a bonus. “Laura’s a good cook and loves baking and whenever I was hungry I would show her the middle finger and that would get a nice little caramel slice over the line,” he says with a smile so sweet you feel motivated to bake him a cupcake yourself. Wholesome much?

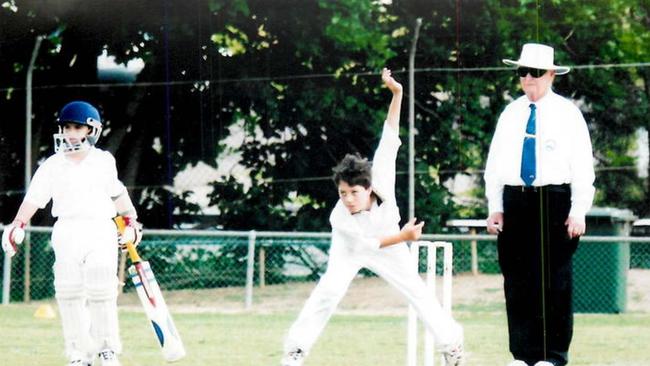

Life came at young Patrick James Cummins fastafter that. One year he’s running around with the local Glenbrook cricket club, where his speed is something of a concern for batters and their loved ones – the mother of an opposition batsman who remembered him from a previous encounter is said to have asked him to back off a little this time around. Then it’s up a notch to Penrith, where he makes his first-grade debut and a search party finds the missing bail from stumps he has shattered on the other side of the boundary line. Next thing you know the NSW Blues call him up to play a few Sheffield Shield games with the big boys. All of this and he’s not even old enough yet to drive a car – which is a bit unfortunate when you live two hours from town. And then, at the age of just 18, he’s standing quietly in line at an airport with the Australian team on his way to South Africa. Lining up with Ricky Ponting, Shane Watson, Mike Hussey and all those other faces familiar from the TV screen.

Getting a few one-day games early was a bonus and dad Peter was on hand to witness it, but he flew home when that leg was done thinking there was no hope the kid would play one of the two Tests. It was a surprise to Pat too. “We flew to Jo’burg and I didn’t think I was any chance of playing but I didn’t care, it was a dream to be on a Test tour, I was loving it,” he recalls. “And then two days before the Test match – this is me being naive and oblivious to everything going on around me – I heard a whisper, I think the physio told me, that Ryan [Harris] is not going to be right for this Test. It was the first I’d heard that he had any kind of niggle. Ten minutes later we had a team meeting and Michael Clarke said there’s a change for this Test match – Ryan Harris is injured and Pat Cummins is going to make his debut.”

Ricky Ponting presented the teenager with his first baggy green as crowds gathered on a beautiful morning in the Highveld in 2011. Soon after, Cummins was cradling the new ball and eyeing South African captain Graeme Smith from the top of his mark. “I remember thinking, I’ve got the baggy green and that’s one thing, but then I looked around and saw Michael Clarke and Ricky Ponting and Mike Hussey and Brad Haddin in the change room and I thought, ‘Wow, this is the same Test cricket they play on Channel 9 every summer’.

“I started off with a bit of impostor syndrome and wondering why I am here. When I was at the top of my mark I was thinking, ‘Don’t embarrass yourself, don’t go for eight runs an over, just land the ball on the pitch’. After my first spell it quickly became just another game. I thought, ‘I’m here, these players we are playing against are just people like me, there is no reason why I can’t make my presence felt and have a crack’ and I remember turning quickly from ‘How the hell am I here?’ to ‘All right, what do I need to do to try and win this match?’ Before lunch the bearded Hashim Amla aimed an airy drive, the ball caught an edge and Ponting caught it at head height in the slips. Cummins had his first wicket.

Three days later, Cummins was holding the ball up to the crowd after knocking over Morne Morkel in the second dig. He had taken five wickets on debut. Soon after he had 6-79 and his efforts had given Australia a chance of victory.

On the fifth and final day, showing the sort of audacity only a teenage fast bowler could summons, Cummins nonchalantly heaved a short ball through mid-wicket for four to help Australia secure a nailbiting win. The next and only other batsman, Nathan Lyon, was so sick with worry he sat in the dugout with his head in his hands.

Prior to that, the highlight for Cummins being with the Australian side on an important tour was the food and the freedom. “Every night we’d go out for dinner, which seems trivial but for an 18-year-old that was a novelty, going out and ordering your own food – anything you wanted to eat,” he recalls. Night after night he scoffed the free sausages and bread that came with the menus at Johannesburg’s famous Butcher Shop & Grill while listening to Mike Hussey and Shane Watson tell stories about international cricket. Then came steaks so big they’d make a hungry teenage fast bowler choke. At the end of every meal they threw credit cards on the table, wiped their chins and walked out. Nobody had to clear the plates, wash or dry. “I couldn’t believe I got to have an entrée and main course every night,” he says.

He was named man of the match and attracted attention around the world. “No 18-year-old in cricket history could have enjoyed a debut as extraordinary as Man-of-the-Match Cummins,” noted the online bible Cricinfo. Christopher Martin-Jenkins, the respected English commentator, had seen enough to declare the brightest of futures for “a fast bowler of unmistakeable quality”, comparing him to Dennis Lillee, Glenn McGrath and Ray Lindwall. “He appears destined to become a household name far beyond his native Sydney, Martin-Jenkins said. “As yet, he is nobbut a lad, of course, but a strapping one. He has the height, at 6ft 3in, the solid build, a strong, balanced action that produces balls of about 90mph without undue strain and – which those who picked him so young had to take on trust – a perfect temperament. Bowling (and, briefly but crucially, batting) with a smile rather than the more fashionable fast bowler’s curse on his lips, he is going to be a boon to the game wherever he plays.”

Or whenever he plays. Cummins went home and six years would pass before he would play another Test match for his country. Something that had come so quickly and easily became painful, difficult and distant. It’s a little disconcerting to note that his first home Test was in the 2017-18 Ashes series.

Cummins had developed a sharp pain in his heel at the start of the second innings in South Africa but they’d juiced him up with painkillers at lunch and it got him through. After the break he took two wickets in two balls but after the match he limped off into long frustrating years of stress fractures and rehabilitation. “I found it frustrating, I always loved Test cricket, I’d had a taste of it and was desperate for that second Test match,” he says. He’d still train at the SCG and when fit would tour with the one-day teams. “I was lucky cricket was patient with me, but I was desperate to get back to establish myself as an Aussie player. By 2017 I had been playing for Australia for six years but I still didn’t feel like a consistent member of the team.

“If you have a bad game you feel you can control it, you can work on things and you will get another chance. With injuries, I felt I had no control over them; it was my body being immature. There was always hope – lots of bowlers go through it and come out the other side – but when you’re in the middle of it, it’s pretty hard to take.”

High performance boss at the time Pat Howard remembers Cummins became the pet project of cricket’s sports scientists. He was patient zero for the management and rehabilitation of a young quick. “We aimed to get him to a World Cup in 2015 and four years later he had that medal around his neck. He deserves credit for his patience and so does everybody involved at the time. He’s now reaping the rewards of being an incredibly resilient bowler since he came back in.”

When Cummins won the Allan Border Medal in 2019, Howard was gone from the game but he received a call from the quick thanking him and the medical staff for getting him there.

If you haven’t got the sense of it already, here’s a story that tells you all you need to know about the Cummins clan and the way they roll.

In the lost years, Cummins took up studying for a business degree. He was on injury payments at the time and was dubbed by the ABC’s voice of cricket Jim Maxwell as “Australia’s highest paid university student”. His mum Maria was a teacher and education was not negotiable for Pat – it was what his siblings and all his mates did anyway. Enrolled at a Sydney campus with no provision for student parking, the injured cricketer grew tired of the long commute from the mountains and asked the Dean – tertiary institutions love high-profile sportsmen in their courses and court them accordingly – if he could perhaps use the spaces reserved for senior faculty staff. When his mum heard, she forced him to write a letter of apology for even suggesting such favouritism.

Cummins says it was one of two times he can remember her getting angry at him. “She gave me a ‘who do you think you are’ type dressing down,” he says. “The other time was in school cricket, I was batting, they had six fielders on the boundary, so I swung, missed and got bowled. With the stumps knocked out of the ground I told the umpires I wasn’t out and explained to them for a couple of minutes about fielders out of the ring rules. They said it wasn’t a thing in school cricket so I remember walking off muttering how stupid the rules are and got another ‘who do you think you are’-type dressing down.”

Then again, maybe he never gave his mum too much to be angry about. They’re private people, the Cummins. When television reporters came around to get some reaction after his spectacular Test debut in South Africa they returned with the slimmest of pickings. One of his brothers was a little sceptical of the excitement around winning a Test for his country and told a reporter it was well and good but the kid was yet to win a match in the backyard against his older siblings.

Peter Cummins is a tall, angular accountantwhofancies himself as a leg spinner – “the tallest leggie in the world”, his son jokes. He grew up in Sydney’s Baulkham Hills but when he married Maria they moved up to the foothills of the Blue Mountains, 70km from the CBD, where they still live. Maria taught maths and English; Peter managed a sand mine. Together they volunteer for local charities, feeding the homeless from the back of a St Vincent de Paul food van. Maria, a keen netballer, set up the Sunbirds all-abilities team in 2009. “We had a great childhood and are still really close,” Cummins says. “Spent a lot of time together at home or on family holidays. My main memory is spending every afternoon in the backyard playing cricket or across the road at the school kicking the footy. Everything we did was a contest.”

You might be able to see the city from the lower mountains but the trip in is painfully slow. “Unless you had a reason to go there we could go a year or two without going into the city,” Cummins says. He went to school at St Paul’s Grammar, on the other side of the Penrith Lakes, where he was a prefect. After he played that first Test match, his teachers commented that his level-headedness would ensure a long career.

Cummins talks quietly but when you are a big quick you don’t need to say much if anything at all. Former Test batsman Marcus North got Pat Cummins’ autograph after his first match against the 17-year-old in a Sheffield Shield game at the SCG ahead of the bowler’s Test debut. He didn’t ask for it, but he got it and he’s hung on to it. “It was the first and only time a bowler hit me in the head,” says North, who is Director of Cricket at Durham in England these days. “It was some of the quickest bowling I ever faced. Marcus Harris got my broken helmet after the match and had Pat sign it. I didn’t realise until I pulled it out of my bag a few days later. Pat’s message was ‘Keep your eye on the ball youngster’.”

Cummins doesn’t snarl, snap or carry on but there’s a dodgy stat flying around cricket these days that he has struck more batsmen on the helmet than any other quick going around. His status as the world’s best Test fast bowler has been established quietly, and so too his status as a unique character in the Australian game. Of the captaincy question he says he would be honoured to do the job if asked but is happy to serve under Steve Smith if that is the decision.

He and Becky met in 2013; she’s vivacious and English. “She was in Australia on a 12-month working holiday visa and we’ve basically been together ever since,” Cummins says. “We meant to get married earlier this year, but her family in England couldn’t get to Australia so we cancelled and will do it when we open up again or we’ll get married over there.” He delayed joining the team at this year’s World Cup to be at the birth of their son Albie, which was announced to the world through a social media post that melted hearts.

The new father is never without a book, especially on tour. On November 7, 2020 he posted this message on Instagram (796,000 followers). “Here are 10 of the best books I’ve read this year. Heading into a couple of weeks of quarantine, any suggestions on what to read next.” The bowler’s post had images of Surely You’re Joking, Mr Feynman!, by Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard P. Feynman, Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe, How Bad are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything by Mike Berners-Lee, Nicholas Taleb’s Skin in the Game, Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia and Anthony De Mello’s The Way to Love.

In 2018, NSW teammate Trent Copeland posted on Twitter that he had just witnessed Cummins complete the cryptic crossword inside 30 minutes with clues read to him by a teammate. “I’m actually not very good at cryptic,” says Cummins. “I just had a hot streak and got every one right…”

When Cummins mentioned Dark Emu in a recent interview with The Australian, touching on Indigenous rights and the BLM movement, it sent the angry keyboard warriors of the culture wars into overdrive. “There’s a lot of cricketers who just want to be cricketers and that’s absolutely fine but whether we like it or not there’s millions of people who look to us every time we play and whether we made a statement or not that is picked up,” Cummins says about the reaction. “I think we all have a responsibility to stand up for what is right and use our platform for good and some players are more comfortable in that space than others.

“I saw that [criticism of Pascoe’s book], but then I think some of that doubt has been questioned, certainly 90 per cent of the content is not in dispute… I found it an amazing book. The narrative is quite different to what I learnt growing up in school. I felt, not sure annoyed is the right word, but I felt proud as an Aussie reading it. You think back to the Egyptian pyramids but I find the Indigenous culture as amazing, I find it a waste we haven’t been taught it or understood it.”

Cummins is part of The Cool Down movement, which he says is trying to push governments to act on climate change while addressing sport’s own contributions. “The game has a big footprint – we fly all over the world in jets, we’ve got big stadiums, play under massive lights, the fields use so much valuable water. There’s a lot we can do,” he says. “Sport will be affected, but cricket in particular, we are subject to the elements.”

He notes that games and training have had to be cancelled because of fires, and rising global temperatures are a threat to participants and crowds in some countries. Former NRL chief executive Todd Greenberg, now CEO of the Australian Cricketers’ Association, works closely with Cummins, who became a director of the body in 2019 and drives much of its policy. “He is the real deal,” says Greenberg. “In fact, when I was doing my own due diligence on the role I was taking I saw him as someone to talk to beforehand and his role on the board is one of the reasons I took this job in cricket. He is a high-quality leader in the game.

“The thing I like about Pat is he has views on topics and is willing to express them. He does not sit on the fence and he does not seek to be popular. He has views he believes to be fundamentally right and takes a position on them. This recent issue around his passion for climate change and the importance for cricket to have a position on climate change is a great sign. He’s not looking to put his views in 60 characters on Twitter, he’s looking to play the long game and make sustainable change. He knows he has a significant profile here and abroad and he wants to use that for greater good.”

When Cummins walks into a room people notice, Greenberg continues. “There’s a sense of gravitas. He’s well admired by his teammates. He has a big commercial presence. I think his journey is only beginning in a lot of ways. A cricketer’s life span is relatively short so when you get the opportunity to make a difference, you want to use it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout