Who wants to be a millionaire? These champion quiz nerds do

You might dominate family Trivial Pursuit nights, but that’s a gentle stroll. Australia’s top quiz champions — the Usain Bolts of general knowledge — reveal what it takes to know it all.

Which Peruvian-born American anthropologist …” OK, bad start, I don’t know any Peruvian-born Americans and very few anthropologists. “ … received widespread attention …” Really? “ … and became an important influence on the New Age movement with his books describing his experience as the apprentice of a Yaqui Indian sorcerer named Don Juan Matus? He insisted Don Juan was a real person, but this is widely doubted by scholars.”

Cool, cool, cool. Let me just reach into my big bag of “Peruvian-born American anthropologists apprenticed to a Yaqui Indian sorcerer” names and hope I pick the right one. There are so many to choose from. Let’s say … Sanchez. Is that a common Peruvian surname? I hope so, because that’s my totally well-informed and 100 per cent reliable blind guess.

I’m sitting in a meeting room at the Holiday Inn Sydney Airport, hunched over a stack of papers, wondering why I bothered to fly to Sydney for the World Quizzing Championships, or the WQC to its friends. The WQC is the nearest thing the quiz world has to the Olympics, and woe betide anyone who thinks they will keep up with the Usain Bolts of general knowledge. God forbid you even think you might challenge Issa Schultz, known as The Supernerd on TV quiz show The Chase Australia, who has finished as high as 23rd in the world. For context, the first year I participated, I finished 310th and was happy with that. You might dominate your family’s Trivial Pursuit evenings, but that’s a gentle stroll. Perhaps you’ve even won big on a television quiz show. Irrelevant. Don’t know your Slovakian politicians, or Panamanian songwriters, or 19th-century tunnels of Switzerland? Then don’t expect to win the World Quizzing Championships.

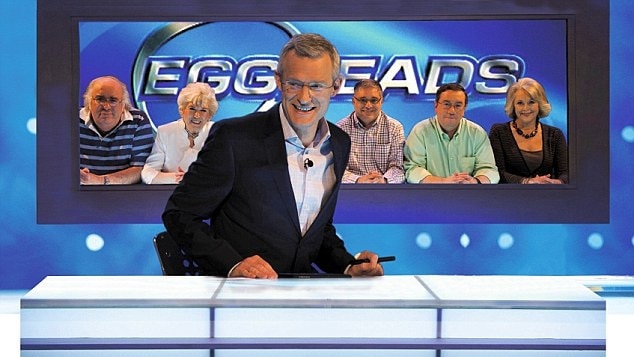

The WQC is like a school exam on steroids. It is run by the International Quizzing Association once a year, simultaneously in 45 countries, in 15 languages, with up to 3000 competitors. Australia is a minor player, with usually just a few dozen participants. The event consists of 240 questions divided into eight categories: culture, entertainment, history, lifestyle, media, sciences, sport and games, and world. The winning score tends to be in the range of 160-170. As of 2021, Kevin Ashman, one of the panellists from the British quiz show Eggheads, has won the world title six times, his fellow panellist Pat Gibson four times and Olav Bjortomt, who writes questions for The Chase in the UK and The Times newspaper, and joined the Eggheads panel in 2021, has also won on four occasions.

The test is conducted over two hour-long halves, which averages out to 30 seconds per question. Usually, the nub of the question is highlighted in bold to help focus your attention as you speed-read through. This is important, because in this style of highbrow quizzing even the simple questions tend to be wordy.

Coined using Greek words meaning “running back again”, what name is given to words, numbers, or other sequence of characters, or complete phrases, that are exactly the same when written backwards? Examples include the English word “racecar”, the Latin phrase “Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas”, the German word “reliefpfeiler”, and in French, “La mariée ira mal”?

Most people will know the answer to this question (palindrome). Half the challenge is wading through the detail to find the question – but even when the questions are short, that doesn’t make them any easier.

Which judoka from the Netherlands is the only athlete to win two gold medals in Judo at one Olympics – in the heavyweight and open categories in 1972? There is no possibility of guessing the answer (Wim Ruska) – you either know it or you don’t. But there are some questions you can work out, and one of the most satisfying parts of quizzing is to come up with a correct guess through deduction.

I can’t believe I plucked the correct response to this question in 2018: One of Hungary’s largest, oldest and most prestigious firms, known for light bulbs and electronics, which company takes its name from a combination of the English and German names for the chemical element with atomic number 74?

I couldn’t name a single company from Hungary, nor tell you with confidence which chemical element was number 74. And I don’t speak German. So how did I work out the answer? I started from a single piece of knowledge: that tungsten is commonly used in light bulbs due to its extremely high melting point. What else did I know about tungsten? That its chemical symbol is W, because it was historically called “wolfram”. And wolfram does sound German. So, then what? Can I put tungsten and wolfram together to form a plausible name? Wolfsten? No, the question listed English first and German second, and I thought there would be a reason for that. I took a stab at Tungsram and was gobsmacked to discover it was the correct answer.

Most people don’t want to think that deeply about trivia, so the World Quizzing Championships is not for everyone. Some come along once, can’t wrap their head around the style of question and the depth of knowledge required and never return. Some, like me, sit there thinking, “What the hell am I doing here?”, but enjoy the experience enough to come back. For others, the WQC is not an experience but an obsession.

You’ve probably heard of Issa Schultz – The Supernerd from The Chase Australia. Issa is so recognisable that viewers sometimes shriek when they see him. You probably haven’t heard of Ross Evans. Every year, at the Australian leg of the World Quizzing Championships, Issa and Ross fight it out for the title of Australian champion. The rest of us make up the numbers. In the 11 years from 2011 to 2021, Issa has won eight Australian championships and Ross three. They are the kind of people who, when asked “Which Peruvian-born American anthropologist …” will know the answer is Carlos Castañeda.

Though they share some similarities, Issa and Ross are very different. Issa, 38, has been a quiz obsessive since his teenage years. He was an almost nightly caller to Tony Delroy’s after-midnight quiz on ABC radio and appeared on The Rich List, The Einstein Factor, Who Wants To Be a Millionaire? and Millionaire Hot Seat. Ross is 68, values his privacy greatly and has had no interest in appearing on a TV show. Only within the past few years, since retiring from work, has Ross taken quizzing seriously.

Much of my quiz practice has taken place organically, over nearly three decades. I didn’t set out to become a professional quizzer. As far as I knew, no such job existed. But all those hours I came home from school and flicked through atlases and encyclopedias, memorised lists of prime ministers and capital cities, obsessively watched Sale of the Century and Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?, trained myself to go on those shows and win money, and wrote thousands of my own trivia questions, turned me into one.

Dictionaries tell us that trivia, by definition, has little value or importance. Dictionaries are wrong. Trivia can bring together families over a board game. It can unite communities at a fundraising quiz night. In a locked-down world in 2020 and 2021 it maintained vital social connections through quiz events on Zoom. It has turned the loneliest hour, midnight to 1am, into a lively hub on national radio. Trivia can provide an outlet for people who struggle to find their place in life, and gives them something of which they can be proud. And if that’s not enough, it can also lead to cold, hard cash. Just ask contestants who have earned life-changing sums of money on TV quizzes.

Just ask me. I won $300,000 on Million Dollar Minute and now, at 5pm on weeknights, I sit in judgment on trivia players – hundreds upon hundreds of contestants since The Chase Australia began on Channel 7 in 2015. As a “chaser” on the show, I know exactly how they feel. Once upon a time it was me trying to win big on game shows. Or win small on radio quizzes. Or win bragging rights at Trivial Pursuit.

You can never predict what an elite quizzer will or won’t know. You wouldn’t look at my fellow chaser on The Chase Australia, Anne Hegerty, who is in her sixties and nicknamed The Governess, and expect her to nail answers about rappers such as Doja Cat or Megan Thee Stallion, but she does, because she studies everything. Likewise, Ross Evans pulls out answers that confound opponents and teammates. In a Champions League match, Ross, Issa and two youngish teammates who were good at pop culture were asked who recorded the 2016 album A Seat at the Table. The young whippersnappers had no idea, but Ross confidently piped up: “Solange Knowles”. The album had been on a list of 2016 music that he’d compiled as part of training for quizzing.

Ross stumbled into high-level quizzing through the happy accident of his regular pub trivia venue, the St George Leagues Club in Sydney, hosting the Australian leg of the WQC in 2008. The style of quizzing suited his knowledge base – strong in history and geography – and he kept coming back. Each year, he took the event more seriously. Now, he spends three or four hours a day, on average, studying, taking notes, filling folders of information that might come up. Information sticks in his brain most effectively if he writes it down on paper; when I call him for an interview, he’s adding notes to his folder on the periodic table. He studies not only to improve his quiz performances but because he enjoys it. “I think anyone who does quizzing has an inquiring mind,” Ross says. “And if you’ve got an inquiring mind, you want to know stuff, you want to understand stuff. You want to know why this happened, or why someone did something, or how this works.”

Like Ross, Issa Schultz finds that taking notes helps his recall. He can visually recall the placement of information on a page, which helps him pinpoint answers. These answers could be in one of the many notebooks he has filled with random lists (I’ve seen inside one of them: a list of video games and their creators was followed by Nobel Prize winners, which was followed by operations from wars). Issa always brings at least one of these notebooks to revise when filming The Chase. He studies every day, either facts that might come up on the show or else building his arsenal of arcane knowledge for the WQC. He might open a book, he might click a random Wikipedia tab, he might revise his own questions and notes.

Issa’s love of quizzing emerged during his childhood in Cornwall, England. The third of four children, he spent the blisteringly cold Cornish winters rummaging through cupboards to find books that caught his interest or the original Trivial Pursuit game, which he read card by card. His late father John ran quiz nights at the local Liberal Club in Cornwall and the young Issa would head to the club after his Scout meetings, taking in the atmosphere of competitive quizzing.

As a high school student living in Australia, he obsessively played the Challenge quiz after midnight on ABC radio, but those were free phone calls. When Who Wants To Be a Millionaire? started and Issa was still living at home, his parents imposed a strict limit on how many times he could call the premium number to register as a contestant. He appeared on the show at 18 and in hindsight knows he was too young to make it big on Millionaire. He recalls struggling in one early question to name the country that Robert Mugabe ruled: he didn’t have the worldly knowledge needed. He edged towards the $32,000 safe level, but used all his lifelines striving for it – and still got the question wrong. It asked which of Heat, Goodfellas, Casino and The Age of Innocence was not directed by Martin Scorsese. Issa was so green that he called him “Score-says” when talking to his phone-a-friend. He had a group of 10 people together in a room for phone-a-friend duties – but none knew the answer (Heat). He locked in The Age of Innocence and crashed down to $1000. “I was devastated,” Issa recalls. “I went in thinking I was going to be the richest kid in town, thinking, ‘I’m going to win this’.”

The show that changed Issa’s life was The Rich List; by this time he was 25 and had far more quizzing experience. The program suited his penchant for list-based learning. It required teams of two to compile long lists of answers to categories such as “US state capitals” or “Hugh Grant films” – which Issa and his partner Reuben nailed. In the two big-money rounds they correctly named 12 ranks in the Royal Australian Navy and 15 (contestants were not allowed to list more than this) letters of the Greek alphabet, to share $400,000.

It was after his success on The Rich List that Issa first attempted the World Quizzing Championships in 2008. He finished second, one point ahead of fellow debutant Ross Evans; the Australian champion was Trevor Evans (no relation). “It’s been an uphill climb ever since,” Issa says. “It’s a continual slog, and I’ve never got tired of it.”

For me, quizzing is still primarily about fun. Yes, I enjoy showing off my obscure knowledge on The Chase, just as any pub trivia player wants to impress their friends by nailing a tricky answer. But what I love more is working out an answer. As Trivial Pursuit writer Bruce Elder said, the great joy in trivia is in almost knowing something.

When we filmed Beat the Chasers in 2020, as Matt Parkinson, Issa Schultz, Cheryl Toh and I paced the floor behind our seats waiting for the next contestant, Matt asked us a trivia question he’d read in the newspaper. What were the only three songs that hit No. 1 in Australia in the 1980s that had the word “girl” or “girls” in their titles?

Together, the chasers pondered this piece of trivia, and it got its hooks into us. We quickly landed on Girls Just Want to Have Fun by Cyndi Lauper and Jessie’s Girl by Rick Springfield. But what was the third? And then, as a Billy Joel fan, it hit me. “Uptown Girl!” I said, and Matt smiled and pointed at me in congratulation. He checked the answers in his newspaper: Girls Just Want to Have Fun, Jessie’s Girl, Uptown Girl. We were about to play against a contestant for up to $100,000, but that tantalising piece of worthless music minutiae could still grab our attention. That’s what good trivia does: it makes you think, “I should know this.” It also brings out the competitive juices – everyone wants to be the one who does come up with the answer first.

Brydon Coverdale is a former cricket journalist who appeared on several quiz and game shows as a contestant before being cast as The Shark on The Chase Australia, where contestants must beat Brydon to win their cash prize. He has also worked as a writer for pub trivia and currently writes a daily newspaper quiz in the major News Corp titles.

Edited extract from The Quiz Masters: Inside the World of Trivia, Obsession and Million Dollar Prizes, by Brydon Coverdale (Allen & Unwin, $32.99) out on Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout