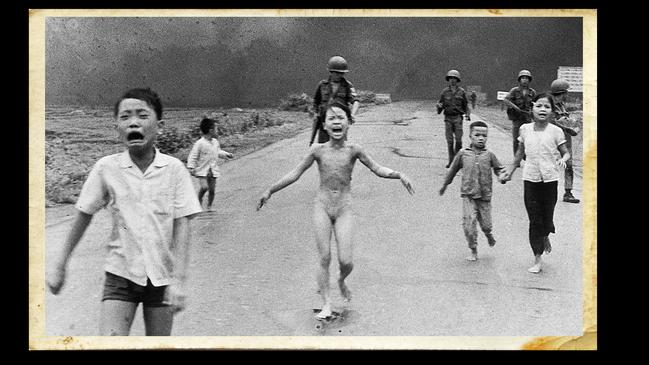

Who took the ‘Napalm Girl’ photograph? Picture editor Carl Robinson says it was not Nick Ut

This iconic image of the Vietnam War won the Pulitzer Prize but now the former AP picture editor who claims he attributed the photograph to the wrong man tells his side of the story.

There was something about the Vietnam War’s iconic Napalm Girl photo that was always on my back. My feelings of guilt, injustice and cowardice about that famous picture weighed heavily for years – no, make that decades – until its 50th anniversary and peak celebrity in 2022. I was now pushing 80 and just couldn’t keep running away from the truth any longer. I finally had to stop, turn around, and look at this private nightmare in the eye.

I started gathering every photo off the internet and from former colleagues documenting what happened at Trang Bang, northwest of Saigon, on June 8, 1972. The sequence. The spectacular and mistaken napalm strike beside the distinctive twin spires of a Cao Dai temple that caused children to flee in panic towards a line of photographers, camera operators and correspondents. Everything I could find.

And out popped an image I’d never seen before. Or maybe I had, but pushed it out of mind like everything else about this story. This one showed the Napalm Girl – Phan Thi Kim Phuc – and other children just after they ran left past two television crews. With the newsmen cluttering up the background it was a much less striking picture, that’s for sure.

Just off to the right, an unidentified Vietnamese photographer in a white shirt and black vest had just shot an image of the children with the open road and clearing smoke behind them. Bloomin’ obvious, I immediately thought. That photographer had to be the real photographer of the Napalm Girl, not that Pulitzer Prize-winning Associated Press (AP) photographer who for decades has been known as the author.

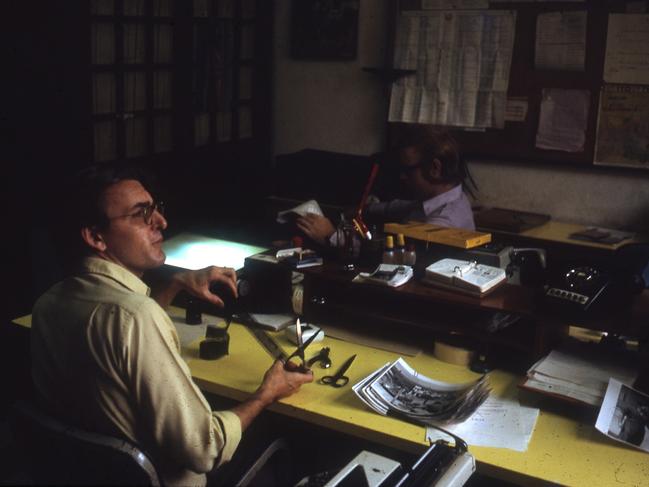

You see, Huynh Cong “Nick” Ut did not take that famous picture. I know because I was a photo editor on the AP desk on that day in 1972. I was just about to type the name of a Vietnamese stringer (freelancer) on the caption for the photo’s transmission to the world when my boss, Horst Faas, leaned into my right ear and ordered in his harsh German accent, “Nick Ut. Make it Nick Ut.”

And I did it. I put Nick Ut’s name on the photo. Although I’d already checked, and it wasn’t Ut who took it, I didn’t feel I had a choice. Faas had given me my job in ’68 after I’d angrily quit my US government job to stay in South Vietnam with my future wife, Kim-Dung. He started my journalism career. I now had her and two children to support. How could I quit my job? I didn’t even argue.

I knew what I’d done was wrong. I was a person of conscience, even a Conscientious Objector; I’d quit the US international development agency USAID as an act of conscience over the war. As veteran war correspondent Peter Arnett walked up to congratulate a startled Nick Ut, I was totally upset. I called a colleague outside and told him what had happened. “How could he do that?” But now we needed to find the girl who, despite his later stories, he did not take to hospital. As the world reacted to the picture over the next couple days, I found Kim Phuc in the very first hospital we visited with the help of fluent Vietnamese speaker Tom Fox and a Vietnamese photographer named Cuong. The only time Nick Ut met her during this period was when he won the Pulitzer Prize the next year and AP needed a photo. We both knew the truth.

I carried that true story on my conscience for over 50 years. An emotional rollercoaster of my own complicity and guilt. Nights taking forever to fall asleep. Dreams. I felt bad every time I saw the picture. But I was always calmed by wise Kim-Dung, who said to just let things be. Let Buddha be the ultimate judge.

I tried to move on, but the photo’s anniversary stirred everything up again. Once again, the Napalm Girl photo was glorified for ending the Vietnam War, ignoring the fact that most US troops had already left and the Paris Peace Agreement was months away. With each telling, the story was embellished further. I could barely watch or listen.

What could I do against such a well-entrenched legend? Who would believe me? Surprisingly, most old wartime colleagues I’d confided in told me to just forget about it – I would lose too many friendships. A couple were quite threatening. I almost revealed the truth in my 2020 memoir The Bite of the Lotus, but held off, fearing legal action and not wanting to distract from the rest of my years in Vietnam.

Naively, I’d always believed my own truth, even shared it privately over the years. But when friends asked who the real photographer was, all I could say was: “Oh, a stringer, a freelancer.” Many Vietnamese at AP and next door at NBC knew who really took that photo; it was an open secret. In 2015, former AP photographer Dang Van Phuoc told me his name was Nghe, and he was a driver with NBC and brother-in-law of sound man TB Than. Nghe became a refugee to the US in ‘75 but returned to Vietnam after his wife’s death.

Now I’d stumbled onto that other Napalm Girl photo, and figured that man in the white shirt and black vest was Nghe. And wasn’t that his brother-in-law sound man next to him? Both NBC and Britain’s ITN later showed the children running past with a side view of the naked Kim Phuc. With more discretion than AP, their full-frontal image of the Napalm Girl had ended up on the cutting room floor.

Post-Covid in August 2022, we were heading back to Vietnam. Forget fighting the established narrative; I now just wanted to find Nghe and – feeble as it sounds – explain what had happened and apologise. But Phuoc wouldn’t provide any more details on Nghe.

After three years away, my return to Vietnam was joyful. I embarked on a motorbike tour with 12 Vietnamese, where I met retired journalist Ngoc Vinh, who introduced me to Le Van, a young reporter. She wrote a feature about my long connection with Vietnam, and we became fast friends. Time passed pleasantly with trips around the Mekong Delta and Phu Quoc Island, but I still had no idea how to find Nghe.

Then an episode occurred that renewed my determination to expose the truth. Jim Laurie, who’d stayed behind with NBC in ’75 after the Fall of Saigon, contacted me. He was lecturing on a luxury cruise, highlighted with Nick Ut and Kim Phuc’s return to Trang Bang “together for the first time in 50 years”. He recalled that I had mentioned my qualms about the photograph before, and asked me to refresh his memory on what I’d previously told him.

In a long email reply, I recalled what happened that day at AP and how Ut’s name went onto the photo. I also shared Nghe’s identity and NBC connection, and how I’d found that photo which I believed showed Nghe at Trang Bang. I didn’t hear anything more. Just a local story from a friend in Hanoi about Ut’s welcome into the Vietnam Journalist Association Hall of Fame.

Jim began posting about the cruise on Facebook as they sailed south from Hai Phong, Da Nang, Nha Trang, and finally up the Saigon River into Ho Chi Minh City. Ut’s ship was arriving the next day. It was finally time to get my story out and clear my conscience. I reached out to my new journalist friend Van and told her the true story of the Napalm Girl picture. It was the beginning of a two-year long collaboration with Van, as dogged a reporter as one could imagine. She briefed her editors at Thanh Nien, Vietnam’s second largest circulation newspaper, but they wanted my proof, something public from me. First, I suggested finding Ut, asking him point-blank if he really took that photo and recording his reaction.

With the ship now in Saigon, I put Van in touch with Jim Laurie. The next day’s tour highlight event at Trang Bang with Nick Ut and Kim Phuc was private with no journalists invited – but Jim believed my story and agreed to talk to Ut. When he mentioned my name at breakfast in Siem Reap in Cambodia at the end of their tour, Ut angrily dismissed me as “crazy” and stormed off. Jim declared laconically, “The truth will die with old men.”

But at least Van was now on the case. She approached Ut during one of his downtown walkabouts and explained she was researching a story on other Vietnamese photographers at Trang Bang that day. Ut claimed he was the only one, saying everyone else was out of film or missed the shot. When Van mentioned Nghe’s name, he quickly replied, “Maybe he’s dead.” He restated his claim of personally taking Kim Phuc to the hospital, driving her there himself in the AP car. He promised to see Van again after opening a Leica exhibition in Singapore, but never got back in touch.

Van and I agreed finding Nghe was crucial. Despite her efforts, her editors rejected running a “Looking for Mr Nghe” story. But I also knew in the gossipy world of Vietnamese editors that authorship doubts now surrounded the famous Napalm Girl photo. I also was fortunate contacting former AP darkroom technician Luu Xay in California, who confirmed Nghe was the true photographer, once lived nearby but had returned to Vietnam to remarry, and was always distressed about the Napalm Girl photo. Despite this, we still couldn’t locate him.

While Van continued her search in Saigon, I reviewed old emails and recalled something that Mort Rosenblum, a fellow AP staffer, had mentioned when the Napalm Girl story surfaced in my Google Group “Vietnam Old Hacks” after a 2015 reunion in Saigon. In a heated exchange after someone mentioned my story, former AP reporter Peter Arnett insulted me and threatened legal action. I’d actually reached out and told Arnett the true story back in 2009, not long after starting up the Vietnam Old Hacks group, naively expecting a sympathetic hearing, but he was immediately defensive. And it was the same blindly vehement defence from him in 2015. The online group of old wartime colleagues was never the same after that blow-up.

Rosenblum emailed me privately, musing about a story that had been circulating for years that Nick Ut had not taken the photo. Moreover, on a trip through Vietnam in 2011, he’d shared that information with British photojournalist Gary Knight, who was surprised and thought of writing something at the time. I decided to email Knight, and he immediately agreed to interview me and find out more.

Knight’s wife Fiona Turner and Terri Lichstein, both Emmy Award-winning TV producers, joined what soon turned into a documentary project with Vietnamese-American director Bao Nguyen following Knight’s investigation. After an initial interview with me, they hired Van back in Saigon.

Nghe still needed to be found, but nobody had his full name, much less his que huong, or homeland, in Vietnam. Wartime Vietnamese photographers who weren’t affiliated with NBC or AP that Van contacted in Saigon all still believed Nick Ut had taken the Napalm Girl picture, one even claiming he’d shot the image long-distance with a 500mm lens. They hadn’t even heard rumours to the contrary.

In March 2023, Knight was heading to Vietnamwith renowned war photographer James Nachtwey and, in something of a coincidence, Nick Ut for a photographer workshop in Hanoi. At the same time, Turner asked me to fly to Saigon for an extended interview to record my story. “Well, no way Kim-Dung’s going to let me go up there by myself,” I said. I suggested that we both go. My wife was reluctant – she was afraid of the bullying and opprobrium that would surely follow, and wasn’t keen on going public – but finally agreed.

In April 2023 we returned to Saigon. I was told to keep my trip secret and avoid downtown, where Nick Ut might be wandering around. The shoot went well: a three-hour interview with Knight, an hour with Kim-Dung, and additional footage in downtown Saigon: me on a motorbike, a favourite temple and a pho dinner at home. After Knight left for the US, I had a strategy session over lunch with the two producers Turner and Lichstein, Van and Kim-Dung.

The crew still needed to find Nghe. One source does not make a story. But where was he? And after Nick Ut’s throwaway line, was he even alive? Turner and Lichstein had a list of foreign media at Trang Bang and would interview them, but many leads turned out to be dead ends. NBC cameraman Le Phuc Dinh and the legendary Vo Brothers had passed away. We hoped to find Nghe’s full name among the Vietnamese journalists who’d worked with US news companies during the “secret airlift” before the Fall of Saigon.

Van was tasked with tracking down Hoang Van Danh (or Doanh), who’d taken that key picture at Trang Bang showing who I believed was Nghe. He was also a refugee but had later returned to Vietnam to start a furniture business, which had subsequently failed. We thought of trying local priests in Ho Nai, where many Catholic northerners from 1954’s division of Vietnam might have known him, but all leads seemed like rabbit holes.

Then Kim-Dung suggested asking Ngoc Vinh, my motorbike friend from the northern trip the previous September, and Van’s journalistic mentor. With more than 20,000 Facebook friends who followed his brave postings on corruption, perhaps he could help search for Nghe? Turner and Lichstein agreed this was a good idea. As they flew out the next day, Vinh – who’d met and interviewed Nick Ut years before – came to the house and agreed to help. I wrote up a post with three pictures for Vinh’s Facebook page, looking for Nghe.

We had only a few days left when I met up with Van for early morning coffee in a crowded wartime housing estate nearby. A single mum in her late thirties, Van was brought up in northern Vietnam’s Thanh Hoa Province; her father was a journalist who’d covered his own war, Vietnam’s invasion and occupation of Cambodia in the 1980s. Van was a determined collaborator, her online Vietnamese-English dictionary always handy for unfamiliar words. She called me Chu Nam, or Uncle Five, after my wife’s family number. I was teaching her about life and work in Saigon during the war, a fading and repressed public memory.

Two days after Vinh’s Facebook post, Van’s phone rang as we drank our usual café sua da, or iced coffees. It was Vinh. Van’s eyes lit up and met mine as she pointed at her phone. After signing off, she took a deep breath and announced, “We’ve found Nghe!”

Nghe had called Vinh after a friend in America saw the Facebook post. I was overwhelmed with emotion, almost bursting into tears. Nghe was in Vinh Long, about three hours away in the northern Mekong Delta. Van immediately rented a car with Vinh for the trip. Overjoyed, I returned home and woke Kim-Dung to share the news. At last, we had found him!

I immediately emailed Knight, Turner and Lichstein – all jet-lagged from their flights home – and later Zoomed with them. “Now we’ve got a real story,” Gary said. They decided to return to Vietnam, so I cancelled my flight back to Australia. A feeling of true contentment washed over me. The next morning, I visited the National Temple to give quiet thanks to Quan Am, Goddess of Mercy, and sat in the shade feeling a gentle breeze wafting over me. What calmness I felt.

Van and Vinh came around for a debrief after their late return from Vinh Long. Van had sent pictures with Nghe – and yes, it was definitely him with the distinctive forehead in Danh’s photo. They’d had lunch together and visited the house Nghe shared with his girlfriend Yen, after his second wife took everything away. Now living in Southern California with his daughter, he was only back in Vietnam to resolve his divorce.

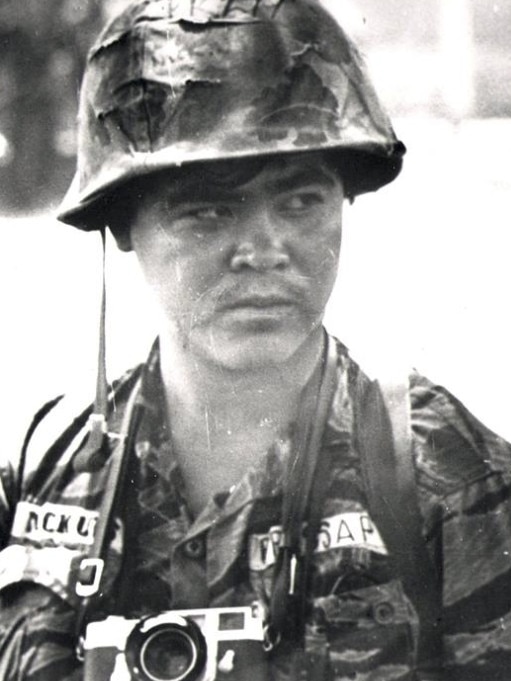

Nghe’s full name was Nguyen Thanh Nghe; he was born in Vinh Long in 1937, making him 86 years old. He was an ARVN cameraman who freelanced for western news companies but wasn’t an NBC driver, just filling in that day. He was indeed the real photographer of the Napalm Girl picture. That was him alongside the film crew in that white shirt and black vest.

Was he angry and bitter? No, he’d said – after the Fall of Saigon he’d moved on with his life because he had a family to support, and besides, he was a refugee and had no way to confront AP. No one had paid him any attention until now. “I have no more evidence,” he told Van. “I am zero. Meanwhile, Huynh Cong [Nick] Ut is a hero. This is unfair.”

The following day, back at home, I was working upstairs and Kim-Dung was watching TV nearby. Her phone rang. Van had bad news: Nghe had suffered a stroke and was headed for a hospital in Can Tho, 60kms away. The grim news continued with two brain bleeds; Nghe was in a critical condition. What a shock from yesterday’s total elation.

Turner and the team reconsidered their return. Even if Nghe survived, they reasoned, his ability to speak was uncertain. I prayed again to Quan Am, now in desperation.

The next morning began with a huge downpour – it was still too early for the rainy season, but symbolic, I thought. The heavens crying for Nghe. I had coffee with Van again, my mind now on possibly attending a funeral. At a minimum, I vowed to slip a copy of that famous Napalm Girl photo inside Nghe’s casket, where it truly belonged. Our mood was grim.

Kim-Dung was at the dining room table when her phone rang. It was Van again. Nghe was awake, not in a coma, and could talk, hear and move all his limbs. He couldn’t eat with a tube still down his throat, but it was a miracle! A video showed him waving, and our spirits soared. His family arrived from America and the documentary team was back on.

With the team returning a week ahead, Kim-Dung and I took a much-needed break in Dong Thap Province in the western Mekong Delta. We enjoyed four relaxing days with motorbike runs along the Mekong River. Then we headed to Can Tho to finally meet Nghe on the eve of Anzac Day 2023.

The film crew had interviewed Nghe in hospital with his daughter Jenny, who’d just arrived from America, and were satisfied he was indeed the real photographer of the Napalm Girl photo. Bedridden from his stroke, his speech was slurred but recorded well. My turn was the next morning.

Kim-Dung and I had started our romance in Can Tho in ’67, when she was on a secretarial course for USAID. I later resigned in anger over the Tet Offensive, with half the city in ruins. Today’s 10-storey SIS Hospital, specialising in stroke treatment, blew us away as we headed upstairs and set up in a small seating area outside a conference room, with the usual bust of Ho Chi Minh at one end.

After some time, Nghe was brought in in a wheelchair and we were left alone looking at each other. I knew he spoke and understood English, so I introduced myself slowly and clearly, explaining that I’d been the photo editor at AP in 1972 and had been ordered to put Nick Ut’s name on the photo. From behind the closed doors of the adjoining conference room, there was a sudden outburst from his daughter Jenny as she collapsed in tears, screaming and shouting. I could barely finish my apology for what had happened all those years ago. Tears flowed down Nghe’s cheeks as I said sorry.

With his stroke, I could barely understand Nghe, but my most vivid memory of our meeting was that emotional reaction from his daughter who, along with her brother, had lived with their father’s story all their lives. Jenny soon came out, embraced me and called me her family’s angel. I had finally righted a terrible wrong.

Now there were two of us – like a mirror – and it was all on film for the world to see. At last, there was justice and redemption for the real photographer of the Napalm Girl picture.

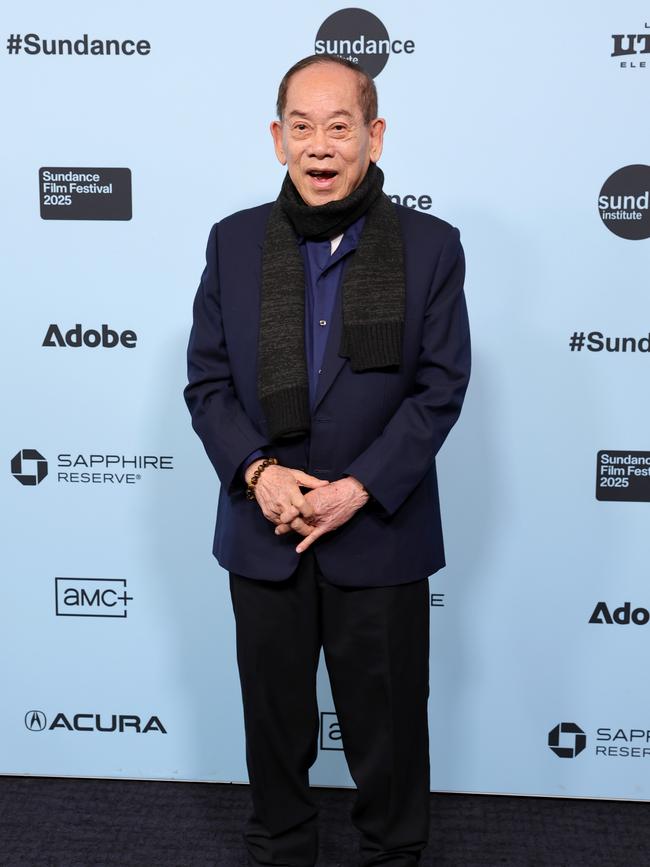

Post-script: US-born Carl Robinson has lived in Australia since after the Vietnam War. He and Nghe attended the premiere of The Stringer at the Sundance Film Festival on January 25. Prior to the premiere, AP published a report refuting the claim that Nick Ut did not take the “Napalm Girl” photograph. Asked by this magazine if it will continue to credit Ut with taking the image, AP responded: “We are committed to a truthful history of the photo and are continuing to collect information and investigate … and will follow up once we have the chance to fully review the film and additional materials.”