Warwick Smith: Australia’s Mr China

Nurturing the relationship with our mighty neighbour has never been trickier.

Sydney businessman Warwick Smith still remembers his first trip to China more than 30 years ago. The young lawyer from a prominent Tasmanian wool trading family had won the seat of Bass for the Liberal Party in 1984. The Hawke government was in power and Australia’s ties with China were opening up when, two years later, Smith and several other young politicians and staffers were invited to visit on a political exchange program. “We landed in Beijing. It was a semi-military airport, nothing like it is today,” Smith recalls. “There were a mass of bikes — none of which had a light on them. Everyone had grey clothing. You wouldn’t know it was the same nation as it is today.” Smith is sitting in his office in the Sydney headquarters of billionaire businessman Kerry Stokes, where he works as an adviser; his gold Order of Australia medal is pinned to his black suit. The walls are tastefully decorated with works from Stokes’ collection, the biggest private art collection in Australia.

“We went all over China,” Smith continues. “I got a very good feel for the country. I loved it.” A bespectacled and unassuming man, Smith was, even then, a consummate networker. And so it was that a contact he forged on this trip would later prove pivotal in smoothing his way in China.

Back in Australia in the years after that visit Smith’s attention was back on domestic issues as he handled ministerial duties in the Howard government before losing his seat (for the second and last time) in 1998. Now, China is firmly back in his sights. In his own way, which mixes politics, business and networking, Smith, 65, has become Australia’s Mr China, playing a low-key but crucial role working to improve relations with our largest trading partner and the world’s second-largest economy at a time of deep divisions between business and national security interests. Some say the Australia-China relationship is at its lowest point for many years, a situation the Government and business groups are trying to remedy. It’s a delicate balancing act, given Australia’s economy is highly dependent on its $200 billion-plus trade with China.

Earlier this year the Morrison Government called on Smith to oversee the establishment of a new National Foundation for Australia-China Relations, which replaces the 40-year-old Australia-China Council. He was invited by the Business Council to chair its China Leadership Group, a committee he is using to provide regular briefings to senior business people. And later this year he will participate in the latest Australia- China high-level dialogue in Australia, the seventh time he has been involved in the talks.

Some of Smith’s associates jokingly call him the “chairman of everything” for the many roles he plays in the private sector (he is chairman of the advisory board of Stokes’ Australian Capital Equity, and a director of Seven Group Holdings, Aitken Investment Management, Estia Health and Magnis Energy Technologies, as well as a former chairman of online stockbroker E*Trade) and in advising government, with his roles including a review of trade agency Austrade last year.

But it is his work as an adviser on relations with China that is now testing his skills. As prime minister, Bob Hawke had spearheaded a much closer relationship between Australia and China, helping to open up the iron ore trade, making connections with senior leadership and visiting the country many times. Much has changed since then, with China now a world power keen to exert its influence. Questions are being asked about the extent of that influence in Australia while world markets are thrown into turmoil by a trade war between the US and China. The Government is wrestling with increasing pressure from the Trump Administration to stand up to China.

Kerry Stokes frankly admits to being concerned about the state of Australia-China relations. “Anybody who cares about our position should be worried about our position with China,” says Stokes, whose investments in China date back to the early ’90s. “I am very concerned about our relationship with China and what it means for our trading position. Warwick’s activities in China are really important nationally.”

Asia Society Australia chairman Doug Ferguson, a KPMG partner who first met Smith in Beijing 15 years ago when Smith was working for Macquarie Group, has a similar view. “These are very complex, challenging times which require deeply experienced and well connected Australian leaders to negotiate behind the scenes with both Chinese and American counterparts,” he says. “I can’t think of anyone who matches Warwick’s decades of senior leadership experience and networks in politics, business and within global institutions interfacing with China.”

Smith says the time is past for “a platitudinous, business-as-usual approach”, conceding “these are serious and complex issues for our nation. Australia effectively swims between two empires. We seek not to run into the rocks.” But he warns that there are no lifesavers in the current situation. “We increasingly need to survive on our own wits and capacity, to actively engage both on security and long-term partnerships with the US, and with our strategic trading and engagement with China, which has grown proportionately to be one of the most important of any country in the world.”

Smith says the new Foundation for Australia-China Relations will be an exercise in soft diplomacy. “A trading nation needs strong and effective soft diplomacy across a range of activities,” he says, acknowledging the inherent difficulties in Australia’s complex relationship with China. “We don’t want to lose our trade with China but we don’t want to give away our values. We need good people to work together. No one person has the answer.”

Smith would still love to be in politics in his dream job as trade minister. But in a world where former politicians can struggle to establish themselves in business, he has managed to create for himself a successful second career. His influence means he can have quiet chats with the prime minister on Australia’s foreign policies and he’s connected with the highest level of business and politics. “Warwick is one of the few retired federal ministers to make the successful transition to the corporate world,” says Albert Tse, the Brisbane- based, Hong Kong-born businessman (and son-in-law of Kevin Rudd) carving out his own role dealing with China. “A lot of ex-ministers have tried to imitate his success but have not gone on to be quite so successful.”

Tse developed a close working relationship with Smith when he was based in Beijing for Macquarie Bank working on the stock market listing of the Agricultural Bank of China in 2010. One of Smith’s skills, Tse points out, is his ability to deal across the political spectrum. He had a long-time working relationship with Hawke and counts former federal minister Craig Emerson as a friend. “He has always been a guy who is comfortable with both sides of politics,” Tse says. “He is an ex-federal minister in the Liberal government but [then foreign minister] Kevin Rudd appointed him as chair of the Australia-China Council in 2011.”

Smith has been carving out his own path since he was a child. The eldest of three children born into a wool-processing family in Launceston, he and his siblings were sent to boarding school from a young age. Smith was nine when he and his younger brother Quentin were called in by the headmaster in 1963 to be told their father, Andrew, had died at the age of 51. They soon learnt he had taken his own life due to the stress of business worries. Once the largest employer in Tasmania, the family firm was suffering from a downturn in the wool business. As young Warwick knew full well, this was the same path taken by his grandfather, Leslie William Smith, who suffered depression after a business dispute and also took his own life in 1950 at the age of 52.

His father’s funeral would be the first and last one Smith attended. He declined an invitation to attend Hawke’s funeral this year. “I went to one,” he says quietly, “and I was never able to get it out of my mind. It was traumatic.”

Soon after his father’s death, his 35-year-old mother Ava moved to the US, leaving her three children in Australia. “The three of us grew up in boarding school and stayed with different families during the holiday times,” Smith recalls. “It’s not something I talk about,” he adds quickly, breaking the silence with a nervous laugh. He spent time in Connecticut in high school as an American Field Service scholar before going to the Australian National University in Canberra to study law, history and political science.

While his father’s business, which sold wool products to Japan and South Korea, gave him an insight into the potential of trade with Asia, his mother gave him an interest in Chinese culture. Returning to Australia in 1974, a decade after her husband’s death, she opened the Kansu Gallery of Chinese art in Sydney’s Hilton Hotel.

By this time Smith was studying in Canberra, but he would go to Sydney during the holidays and help out in the gallery. After graduating he worked in a Launceston law firm that acted for the Liberal Party. He took his seat in parliament at the age of 30, and in 1991, under opposition leader John Hewson, was given a portfolio that was to be his big breakthrough: opposition spokesman on communications. It was a role that brought him into contact with members of the country’s leading media families, including Seven Network chairman Kerry Stokes.

When he lost his seat in March 1993, Smith’s interest in communications policy saw him move to Melbourne to become Australia’s first telecommunications ombudsman. But he wanted to get back into politics, hoping for a seat in Victoria rather than the volatile world of Tasmanian politics. Howard told him the best thing he could do for the Liberal Party was to win back his seat of Bass, which he did in the election of March 1996 when Howard led his party to victory.

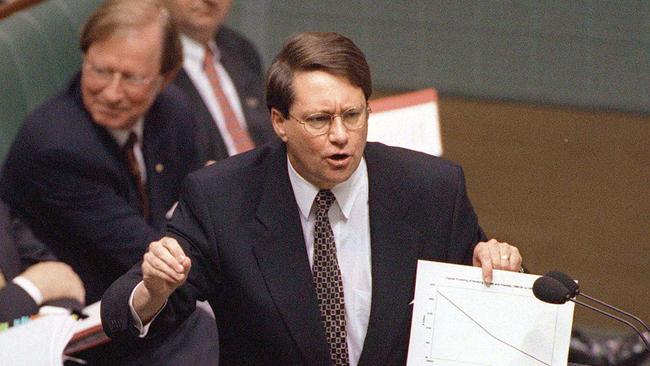

It was a good time for Smith. He was appointed minister for sport, territories and local government and minister assisting the prime minister for the Sydney Olympics, and then minister for family services. But the tides of Tasmanian politics turned against him two years later in the 1998 election when he again lost his seat.

By then 44 and the father of three young children, he was out on his own again. Stokes offered him a job in his media and investment empire but Smith wanted to challenge himself to learn new skills. Macquarie Bank head Allan Moss threw him a lifeline: a job in Sydney to help set up a new division of media and telecommunications. Smith credits Moss for teaching him about banking and leading a business organisation. “Here I was, a bloke from Tasmania who had no money because I had been in politics since I was 30. My job was to be the human sponge. I had to learn every day how to become an investment banker.”

Smith was instrumental in setting up Macquarie Bank’s new telecommunications, media, entertainment and technology group. His interest in China saw him attend several of the early Boao Forums established in 2002 by a group of former politicians — including Hawke — with an interest in Asia. The idea was to set up a conference that would be the Asian version of the high-profile annual event in the Swiss ski resort of Davos.

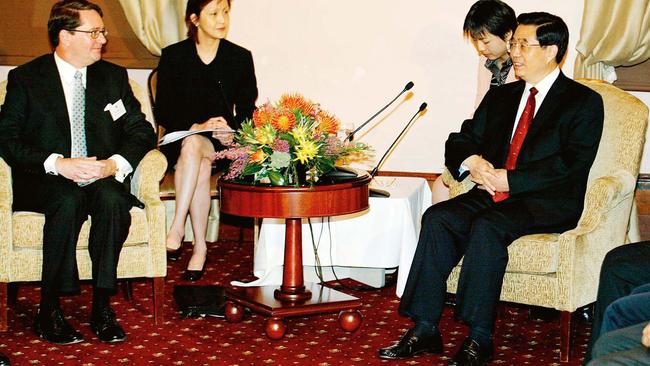

Keen to remind the audience of the Australian involvement in its establishment, Smith stood up at one early forum to ask a question of Hawke. Afterwards, he was approached by a Chinese woman who asked if he remembered her. It was Jihui Xia, the woman who had guided him and his parliamentary colleagues around China way back in 1986. That meeting proved invaluable. Xia, they found out, was very well connected. “That evening she introduced me to Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji, who was attending the forum. She rose to be the first assistant to the number four man in President Hu Jintao’s line-up. She became a very important person. I was able to take Allan Moss and Kerry Stokes to China at different times and introduce them to some of these senior leaders.”

When Macquarie opened an office in Beijing its clients were impressed to see a photo on the wall of Smith meeting Hu Jintao. In 2007, with his mentor Moss set to retire as chief executive after 15 years, Smith left Macquarie Bank. This time he accepted a role with the Stokes family company while continuing to work part time with the ANZ Bank. Both Stokes and the ANZ were expanding their roles in China (Stokes has since sold out of operational businesses in China).

Smith has not lived in Tasmania since the late ’90s but still sees himself as Tasmanian, even as he commutes between a farm in Bowral, NSW — where his wife of 44 years, Kathryn, lives — and a unit in Sydney. He also travels to see his daughter Sabrina, who lives in a remote village in Rwanda with her husband, genocide survivor Nepo Sibomana; they have a young daughter, Raphaella, and run the Mustard Seed Institute, a social enterprise to provide opportunities for Rwandans.

Smith argues that Australia needs to see itself aspart of the “Asia vertical” — a time zone region extending from China to Australia and a region of growing economic wealth and trade opportunities. “Our trade flows have been shifting in the past three decades from Europe and North America to Asia and, more importantly, China,” he says. “It’s a giant economic neighbourhood with Australia in it.”

What is notable about China, Smith says, is its confidence in its role in the world. “The big change over the last 30 years has been assertiveness,” he says. “It has built up an economic growth engine which is impressive by any measure in world history. At every level it has become stronger — science, technology, engineering, military, space. The financial reach of China has grown dramatically, as has the deeper reach of its state control.”

While this new assertiveness has prompted concerns in the West, Smith says it also needs to be seen from the perspective of Chinese history. “The Chinese are coming off a very low emotional base. Over a century of humiliation rides very strongly in the consciousness of Chinese leadership,” he says, referring to the period from the First Opium War with the British (1839-1842), which forced the opening up of the country to Western traders, to the end of Japanese occupation in 1945. “In their view, it is never going to happen again. Their assertiveness is a response to that history.”

Australia needs to understand that China’s system of government is very different from our own, Smith says, while acknowledging that China can be thin-skinned when it comes to criticism. The Chinese Embassy in Canberra issues regular statements on anything it thinks need correcting, for instance. “I tell the Chinese ambassador not to get too oversensitive. When it comes to the newspaper, read the horoscope, I tell him,” he jokes.

He believes that Australia should sign up to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and use its “real global expertise” on areas such as infrastructure building, arguing that Australia has already signed up to support the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which will finance some Belt and Road projects. We should get some of the commercial opportunities from Xi Jinping’s grand vision to recreate the old Silk Road trade routes, he says. “I don’t want Australia to be left behind.”

While Australia is “concerned about the opacity of politics in a one-party state”, he says China also shows concerns about the “robustness” of the Australian democratic system. In navigating the relationship, Australia needs to be both practical and realistic: “We should not seek to replace co-operation at every turn with confrontation.” He says trade with Asia is now more competitive than in the days when his father used to sell wool to Japan and South Korea. “We are a country of 25 million people, which is about the size of Shanghai. We don’t want to get ahead of ourselves, bestowing upon ourselves greater influence than we actually have.”

Smith describes himself as a “transactional guy. I’m not going to get buried in ideological and factional politics,” he says. “I am from a trading and business family. I’m not blindly ideological, I want to test the facts and see outcomes.” He describes himself as a listener, and a fixer, quickly backing away from that term because of its negative connotations. “I’m a listener and a persuader,” he says. “I fix problems.”

And now, three decades after his first trip to China, there are plenty of problems for Warwick Smith to help fix.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout