Trent Dalton’s tales from the bunker: the great escape

A month into the lockdown, our coping strategies are bearing unexpected fruit.

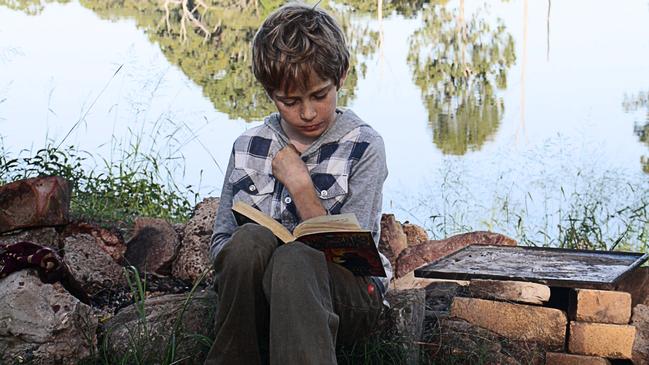

The boy reading his book by the banks of Tinana Creek. Paint this image on the walls of my memory so when I think of the pandemic of 2020 I will think of this barefoot kid, Samuel Marshall, lost in his own wild imagination. Alone but not lonely because that book in his hands – The Burning Bridge by Australian author John Flanagan – is a gathering of friends he won’t ever have to distance himself from.

Nine-year-old Samuel is the youngest of three kids who live with their mum and dad near Maryborough on Queensland’s Fraser Coast. Not far from where he reads, his 12-year-old sister Jill tends a vegie patch she made herself, filled with chilli and coriander. Samuel’s dad Paul started a new job only a month ago and he was told yesterday that he would have to reduce his work hours to four days a week, but when he told his family this news last night he was careful to say that it was only fair he reduced his hours like everybody else and that he’s grateful just to have a job.

Samuel’s mum Melissa is a prison chaplain who knows a thing or two about isolation. She used to teach prisoners locked up in Woodford Correctional Centre, north of Brisbane. Before the virus sent her home to her bunker, she was making regular visits to the Maryborough Correctional Centre to have long chats with inmates about faith, surviving the dark times, what it means to build a life from scratch, what it means to start again.

When Samuel wants to know anything about resilience his grandmother is only a computer screen away. She’s 83 and enjoyed her first Zoom family catch-up last week. Tales from the bunker? Samuel’s grandmother remembers the fear in her heart and in her belly that day, aged six, she had to scramble down into a bunker beneath the Royal Brisbane Hospital because a Japanese submarine had just sunk the Australian hospital ship Centaur off the Queensland coast. Samuel’s mum gets cross with his grandmother because she’s still going to her local IGA and post office every day. She does this because she’s lonely. She lost her husband five years ago and those kind people in the IGA are sometimes as close as company gets for her.

Samuel drops briefly into Woolworths with his mum. Melissa is normally the sort of person who smiles and says hello to complete strangers when she shops but lately she’s noticed a decline in pleasantries in the supermarket. Nobody smiles anymore. Nobody even makes eye contact. Just the hard eyes of one shopper unfairly assessing the health of another. The slightest cough or sneeze feels like a public act of high treason.

Then young Samuel does just that, a full-bodied sneeze not far from the empty shelves for hand sanitiser, and he forgets to put his face into his elbow. Melissa can feel the presence of a stern-looking woman coming their way and she instinctively shields her son from this woman because she’s expecting a torrent of abuse. But the woman smiles warmly at her son and says, “Bless you”. And Melissa knows then that supermarket pleasantries aren’t dead, they’re just a little harder to find, like a 12-pack of two-ply toilet paper and a can of diced tomatoes.

Then Samuel returns home and slips down to his own private universe bunker by the banks of Tinana Creek and he reads about fantastical lands and sword-wielding warriors, dangerous creatures and epic quests. And the boy with the book makes his great escape from Covid-19.

Four weeks in the bunker and my wife and I have escaped into fantasy, too. Each Monday morning we kiss the kids goodbye upstairs then take the long march to work, 15 steps down an internal staircase to the rumpus room bunker with my ol’ workmate, Keefy, the dead stonefish. He’s been floating in preservation fluid for the past seven years and he’s still more animated than a couple of folks I’ve shared office space with. “How was the weekend?” I say to my wife as we take our seats beside each other, doing that little schtick where we pretend to be work colleagues shooting the breeze on another Monday morning.

“Had better,” my wife says.

“How’s that husband of yours going?”

“Pain. In. The. Arse.”

“Have you tried giving him beer?”

“Good advice,” my wife says. “How’s the ball and chain?”

“Light. As. A. Feather.”

My wife reckons we’re living in a kind of very nice low-security prison. Less menace, fewer shivs; more Netflix and chill. She says we’re all finding our own ways to bust out of our temporary clinks.

In a house in Waverley, Sydney, Joan Gates watches her three-year-old grandson run to the backyard with a kickboard, one end of the attached ribbon wrapped around his leg. That’s his surfboard and leg rope, the boy tells his grandmother. Then he dives onto the grass and paddles joyously into the surf in his mind. Kick, kick, paddle, paddle, and then he’s up on that surfboard and he’s riding those monster waves until he gets dumped. “Rode it into the sand,” he clarifies to grandma.

Lexi in Richmond, Victoria, is escaping with her son, Max, on horseback. Max is the rider and Lexi’s the horse, of course, and their mountain trails run past kitchen benchtops and between armchairs and couches. “Because we don’t have anywhere to rush to, anyone to meet, our daily house chores take on a new dimension,” Lexi says. “We don’t just make the bed. First Max and I roll around in the doona on the ground, then we hide in the sheet on the bed, then we wrestle and then he’s thrown on the pillows to squeals of laughter. From both of us. It can take half an hour to make the bed. It’s a gift. There’s no need to rush.”

On the Sunshine Coast, busy mum Patty Beecham escapes into a new Facebook group she has set up. “A women’s-only group called TWANG,” she says. “The Women’s Assets Natural Group. It’s all about championing being braless at home. No visitors, right? So far I’ve posted a few lame Google photos but I think I need to step it up and start promoting home-bound nudity. I’m going to call it NAH – Naked at Home. That’s as far as I’ve thought. Tomorrow I’ll revisit it and do a bit more, but I’m pacing myself. I don’t want to rush things; there has to be something to do tomorrow. There’s going to be a lot of tomorrows!”

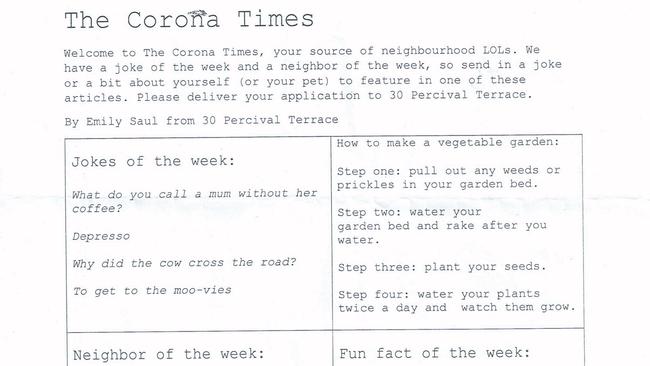

Eleven-year-old Emily in Holland Park, south Brisbane, escapes into words. She’s created her own newspaper, The Corona Times. Publisher, editor-in-chief, chief reporter, fashion editor. She delivers The Corona Times to letterboxes in her street each week. Cracking read. Updates on street activities. A joke of the week. Neighbour of the week: “Mia from No.25 is nine years old and goes to Holland Park State School. She has a red cattle dog named Miley who will turn 11 this year. Mia plays guitar and likes to ride her skateboard and play soccer. She recently got back from Japan so her school told her to stay home for two weeks.” Emily’s fashion tips are the talk of the street: “Denim on denim is a classic look that is comfortable and impressive, so there is no doubt that you will look fabulous while working from home. Achieve a classic yet classy look by wearing reflective sunglasses with metal trim. You can model this look while mowing the lawn or weeding the garden since you can’t go anywhere else.” Emily writes and writes from her bunker, week in, week out, and so makes her great escape from Covid-19.

Some escapes can’t be made so freely. Some truths cannot be run from. Some four-walled realities are only magnified in World War C. Kate in Melbourne is thinking a lot about her marriage. Overthinking it. Long year for the overthinkers. “There’s a sort of grief and pain in realising that your imperfect marriage may actually be beyond repair,” Kate says. “With distractions stripped away, the presence of that other person is not the source of deep belonging, comfort and support that it might be. I hear the dad next-door playing with his kids, and the scorn and shouting in our kitchen feels more wrong. I sit at the dinner table and hear the absence of acknowledgment or gratitude, like an unwelcome guest. The sullen silence of my husband grates. It’s true that you can feel loneliness even when there’s others around. And the emotional seesaw is more obvious. The kids saying, ‘Why is Dad in such a bad mood?’ The notion of the wife and mother as emotional regulator of all things feels totally unfair, and untenable. And let me tell you, a couples counselling session on Zoom is a grim experience. At the end of it you’re left sitting on the sofa in the dying glow of the laptop; left together-alone with your bloody baggage and your family history and your pain.

“Maybe in the weeks to come we’ll discover the art of empathetic conversation. Maybe the arguing of the first few weeks of the new regimen will give way to an acceptance of the way things are. Maybe, with acceptance, will come revelations. Maybe we’ll be laughing over a shared moment and feeling grateful for still having jobs. Feeling the spark of warmth and the support of someone who’s in this with me. Cherishing the children we were blessed with. Owning up to our privilege. In the meantime, I nick out for a mental health walk. I stare at the moon. And I hug the kids and try to give them something rock solid to build a person on.

She finds light relief in Covid memes, in the beauty of the autumn sun slanting into the kitchen in the morning. “And the blowsy late dahlias in the garden; I know they’ll be all over in a few weeks. We have the winter coming. It is the drawing-in time, and this forced seclusion is beautiful, but God, you cannot escape the fissures in your relationships. I know it’s through the cracks that the light gets in, but sometimes it just feels hard.”

In Paddington, Brisbane, 72-year-old Susan gives thanks for the people in her life: two children and their spouses; six grandchildren who live a five-minute drive away. She tries to be grateful always but she wrestles with guilt. It’s the overriding emotion for her through all this, her inescapable truth. “Why guilt?” she asks. “Because I feel that the whole country is being held to ransom to safeguard people of my generation.” She fears for the very ones who are pulling her through this, her grandchildren. “When the world returns to normal, what will their future look like? Will there be jobs for them after uni? Will they be able to make their way in a world which once more rewards hard work and determination?” Then she checks her thoughts. “I expect I am becoming a bit maudlin,” she says. And that’s when she knows she needs to call one of those grandkids.

In Dapto, south of Sydney, high school teacher Benedicte Henry steps into her living room to attend the joint funeral of her two favourite high school teachers when she was a girl. Both have died of coronavirus. She attends the service via her computer screen, the only way she can transport herself to her homeland, Belgium, where it’s taking place. Two teachers, married for almost 50 years. “They died a few hours apart,” she says. “United in life and death, and that is the only comfort for the many people who knew and loved them.”

Madame Valentin was Benedicte’s history teacher in Year 8; Monsieur Valentin was her Greek teacher in Years 8 to 10. It was in Greece – exploring a passion for ancient history that Monsieur Valentin planted in her – that Benedicte met the Australian man who became her husband. Two teachers who changed her life in profound and wondrous ways, farewelled through a computer screen, remembered in her heart. “A couple of dear faces and souls behind the climbing cold figures of the death toll,” she says.

The climbing cold toll. A hundred thousand lifetimes rolled into a six-digit figure blinking in the corner of my computer screen. It’s Helen O’Connell’s job to keep that number down. She sends a message from her bunker, a hospital ward on the Covid-19 frontline. She’s the head of surgery for Western Health, Melbourne. “My big concern right now is making sure we protect all our frontline health workers appropriately,” she says. That, and sorting out the logistics of getting the right staff to the right people. Not easy.

But this is where the light gets in for Helen. “WhatsApp texts from senior surgeons showing their ingenious use of materials from Bunnings to ensure they are protected during surgery but also to show the team how to protect themselves,” she says. The storm is coming, she says. But the light is coming to meet it. “As we prepare for the surge in cases, knowing our ICU capability and its expanding staff will be challenged beyond belief, there will be many more tales from our bunker,” Helen says. “And from the light of our hearts.”

The climbing cold toll. The curve that starts to flatten in my home state of Queensland, making me so deeply proud of every last suburban party animal who dragged themselves away from the pubs on Caxton St; who might keep themselves away this winter from the bronze statues of our rugby league heroes that attract hordes of drunken footy fans every State of Origin season. Let’s knock up another bronze statue in a year’s time to remember how we beat the pandemic of 2020: a simple lounge room scene, a chiselled bronze husband and wife holding a bowl of barbecue chips watching three blokes get married on Tiger King. All you cool cats and kittens. We bloody did it.

Then a tale reaches the bunker from New York. A big-hearted 27-year-old Sydney bloke named Chris Hew who lives with his partner Amelia in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a Covid-19 hotspot. They moved there eight weeks ago. It was their dream. They captured their dream. Had it in their hands. “We both landed dream jobs,” Chris says. “We envisaged nights spent at trendy bars in the West Village, weekend getaways to upstate New York. That is not our reality. Yesterday, New York recorded its largest single-day death toll from coronavirus. The once vibrant streets of Brooklyn are now filled with ambulances and the wailing of sirens. This week I’ve watched as field tents have popped up throughout the park and a navy hospital ship has been deployed to the harbour.”

Some dream. But Chris is finding the light in it all. The light that never goes out in New York. “The city lights have never looked so bright,” he says. “Fresh air has never smelt so good. Amidst all this madness we’re thankful we still have our health, our jobs and each other.”

Meanwhile, back home in Australia, Amelia’s mother, Marg Banks, is doing that thing that all loving Australian mums are so very skilled at. She’s worrying. She’s fretting. She’s waking in the night wanting to hold her daughter tight. “I’m writing this, trying to explain the feeling you have deep down when you know you can’t get to your child if you need to,” she says. “I tell her don’t take risks and please, please don’t get sick, not now, not there. My maternal instincts are going nuts right now with this awful tyranny of distance.”

Far away, yet so close. Or so close and yet so far away. The tyranny of a distance of only 1.5m, the space between a daughter and her ageing mum. The width of the windowpane in Mandurah, Western Australia, that separates Glen and Terry Wootton from their beloved granddaughter, Poppy, who’s too young to understand why they can’t step outside to play.

There’s a distance of more than 15,000km between Jeremy Callaghan’s locked-down neighbourhood in north-west France and the nursing home in WA where his father lives with dementia. Jeremy writes a letter to his dad because he wants to tell him about the strange clapping he’s been hearing every night across his neighbourhood at precisely 8pm. There’s every chance his father might not be able to understand but he writes anyway because it feels good to get some of his thoughts down on paper. He writes about yesterday. Just another day in the pandemic as France’s death toll rises above 14,000. He writes about the colour of the skies this past month: always blue, like the skies over Perth. He writes about how all he wanted to do yesterday was buy a cold beer to reward himself after a hard day’s work. But a walk down the street to buy a six-pack ain’t what it used to be in France. He needed a time-stamped and signed authorisation paper to do such a thing. Police are stationed at points across his block handing out 135-euro fines to anyone without appropriate documentation.

Then Jeremy writes about what he calls “The 8 o’clock” and the first time he heard it. “As my fire roared inside, and I refilled the wood basket with wood outside, I heard it for the first time,” he tells his father. “Into my own isolation and confinement came the sound of others. People I didn’t know. In the distance, people were clapping.” Across France, isolated citizens were opening their windows or stepping onto their balconies to clap and scream joyously at the night sky. What started out as applause for French medical staff has become a nightly round of applause for humanity. “Out of the unusual silence that a virus has plunged us into came a revelation – a reminder that we are a community and that we care for each other. We listened in a kind of silent recognition of all these things that are happening, these extraordinary times that call for extraordinary actions, and we joined in.”

Jeremy raised his hands to that night sky that twinkles over Perth as brightly as it twinkles over north-west France and he hollered and hooted so loud and with such force and such heart that his dad might have been able to hear it in his little corner of his nursing home on the other side of the world. Hear the sound of humanity and gratitude from a distance of 15,000km; hear the sound of the 8 o’clock.

To share your bunker tales, email Trent Dalton at thebunkertales@gmail.com

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout