Tom Slingsby’s road to the top of world sailing was anything but clear water

You don’t want to get in Tom Slingsby’s way. He’s the world’s best sailor and if you want his crown, you’ll have to come and get it.

It’s a beautiful day in Abu Dhabi, warm and sunny, with the sea breeze fluttering off the Gulf like a gentle caress. Tom Slingsby couldn’t be unhappier. This is not his sort of day at all. The wind is too light, too patchy – it’ll be a dog’s breakfast when the racing starts. His hard-charging crew of Australians won’t be able to get the F50 catamaran up on its foils and that’s bad news for their skipper, the man everyone is chasing in SailGP.

He has returned to the fray after missing the previous leg of the global grand prix tour to be at home in NSW with wife, Helena, for the birth of their first child. Could he be human after all, the cynics sniffed? While few Australians would know of Slingsby – testament to the sport’s grindingly low profile here – he’s as dominant as they come in world sailing. You name it and he’s been there, won that: Olympic gold, world titles, the America’s Cup, Sydney to Hobart line honours, World Sailor of the Year (three times) and, yes, every SailGP championship since its inception as a wet and wild answer to Formula 1 motor racing.

Like Slingsby, 39, the format is utterly uncompromising. The 15m boats – 50-footers on the imperial scale favoured by sailors, hence the designation – zigzag around a 2.5km course at speeds of up to 100km/h, ideally riding on the knife-like hydrofoils that jut from each hull. The craft are identical, powered by a solid-block wingsail nearly 30m tall, and crewed by a team of five. The idea is to make the racing a test of skill rather than the depth of the owner’s pockets or access to exotic new tech. Spills and thrills abound on the water; an F50 can start foiling in winds of only 10km/h and literally takes to the air as it picks up pace.

Maintaining that precarious balance atop the waves is the job of the aptly-named “flight controller” who crouches in the cockpit in front of the “driver” (Slingsby in the case of Team Australia), adjusting the foil settings with minute turns of a hand control. Get it wrong and the water around the carbon-fibre nibs will bubble, destabilising the boat. To fall off the foils is to come a cropper in epic fashion: think what it would be like to go from highway speed in your car to a juddering halt in under a second, and forget about being belted into a seat inside the cabin. You’d be clinging to the roof.

SailGP crashes have caused the big, fast cats to flip end on end or break apart, leaving crew members broken-boned and concussed. Slingsby’s had his share of injuries. Par for the course, he says. “It’s sailing on steroids where everything is happening faster, you pay more for your mistakes, you’ve got less time to catch up.”

What he dreads are wispy conditions like these in Abu Dhabi. The Australians prefer it rough and windy, as it generally is on Sydney Harbour. Round eight of the 13-stage 2023-24 competition unfolds there this weekend in what looms as a must-win outing for the home team. A change of the guard is underway, and Slingsby is adamant it won’t be at their expense.

“Honestly, we’ve had a target on our backs from the very first SailGP event in 2019,” he says, ahead of hitting the glistening waters of the Mina Zayed inlet. “It’s human nature. You want to see the underdog win.” He pauses, choosing his words carefully, because he doesn’t want them to be misunderstood or misquoted or, worse, used as ammunition to fire up the opposition. “I remember watching Lewis Hamilton when he was winning everything in Formula 1 and, you know … I ended up wanting him to lose. I had nothing against him but it’s natural to want to see the new guy come in – a Max Verstappen to shake things up. That’s good for everyone. It keeps everyone on their toes. But it doesn’t just happen for the new guys. They have to earn their wins, they have to take them.”

The music is pumping now in the Australian compound: Cold Chisel’s Khe Sanh to blow out the cobwebs, then Slingsby’s personal anthem, the song he always puts on before a race, The Stroke by Billy Squier.

Get yourself together, boy

Stroke me, stroke me

Say you’re a winner, but man you’re just a sinner now.

If Slingsby has a weakness, it’s said to be his temper. Watch out when the “red mist” descends, say those who go up against him. “He can be an absolute prick,” a rival driver confides, a touch admiringly. Another way to look at it is you don’t want to get in his way. Not while jostling for position during a chaotic start, and never ever when the race is on the line.

Slingsby makes no apologies. Why would he? Competitive sailing is as ruthless as international sport gets, and SailGP ratchets the pressure up to a whole new level. The field is a Who’s Who of world sailing sprinkled across 10 national teams competing in the repurposed, $5m-plus America’s Cup boats. There’s New Zealander Peter Burling, 33, the Australians’ bête noire. Team Canada is headed by another top-notch Kiwi in Phil Robertson, a dual world champion in the M32 catamarans. Slingsby’s childhood friend Nathan Outteridge, the 2012 Olympic gold medallist in the 49er class, is at the wheel of the Danish F50. In the hotseat for the British is new driver Giles Scott, a two-time Olympic gold medallist in the Finn class; the 36-year-old has been called up after the abrupt retirement of Sir Ben Ainslie, a hero of Slingsby’s. Another veteran, Australia’s Jimmy Spithill, winner of two America’s Cup campaigns, is cooling his heels after a change in ownership of Team USA. Remember those names: they’re integral to Slingsby’s story.

His rivalry with Burling came to a dramatic head in September 2022 off the French Riviera. The wind was gusting to 60km/h, uncomfortable even for Slingsby. “There was very little grip on the rudders … we were doing 90km/h-plus and side-slipping. I didn’t have much control,” he remembers. Team NZ pounced, coming at the Australians hard on the finish line. Their boat crashed off the foils and was damaged, though thankfully no one was hurt. (Slingsby’s long catalogue of injuries runs from being knocked unconscious to busted knee ligaments and lacerations.)

Burling got the win – and an expletive-laden serve on the race comms from an aggrieved Slingsby, seeing red over what he regarded as a reckless move. Burling, for his part, insists to this day he was within his rights. “My emotions sort of blew over there, and I regret it,” Slingsby says. “It creates a sort of storyline that … Pete and I hate each other when that’s just not the case. We get along well, our wives get along really well. We go out for dinner together. But on the water it’s a completely different story. That’s just the way it has to be at this level.”

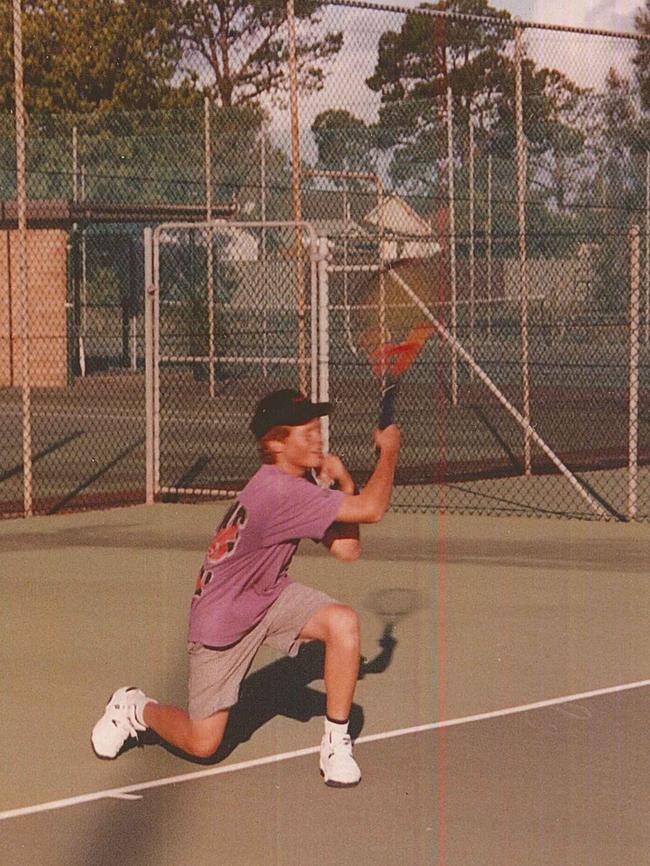

Truth be told, he was no natural sailor. A born competitor, yes, but as a boy growing up on the NSW Central Coast tennis was the sport he loved. He practised before school and long into the evening, every moment he could. His mother, Mavis, understood: a tennis aficionada, she still played in the local competition. Dad David was the yachtie in the family.

They lived on Brisbane Water, in a house backing on to the quiet estuary. Big sister Alana had to pay young Tom 20c a time to take out the sailing dinghy. He was set on becoming a tennis pro, and no one would tell him otherwise. He was good, but not good enough. The writing was on the wall when he was eliminated in the semi-finals of the NSW junior titles. “If I’m honest I was burnt out by my mid-teens. I was losing to people I felt I probably should have been beating,” he recalls. Time for plan B.

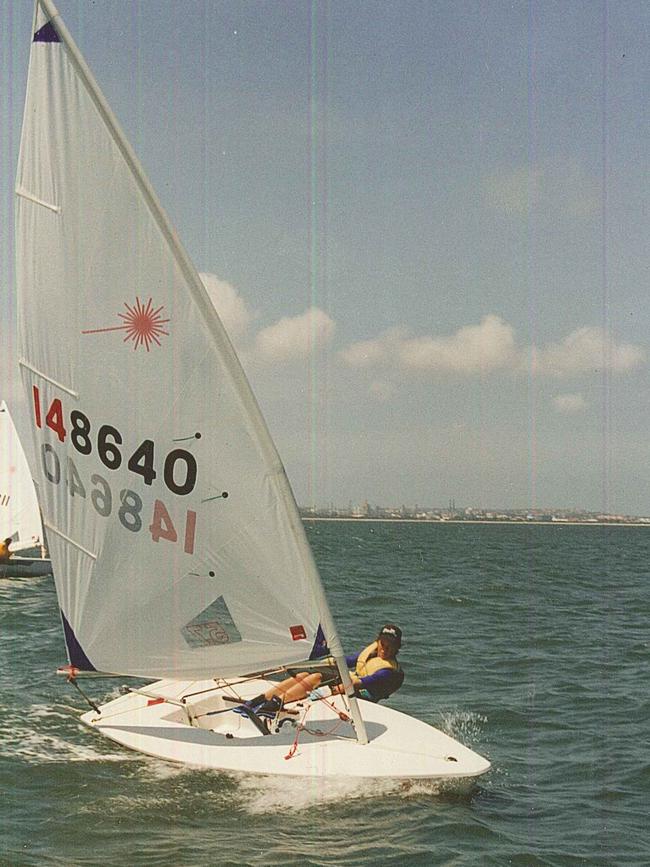

He had always enjoyed sailing, and a lot of his mates were into it. When the Sydney Olympics were on, Tom, who’d just turned 16, would take the train to the city and join the crowd watching the action on the harbour. Britain’s Ben Ainslie, then 23, put in an inspired effort, taking out gold in the single-handed Laser class; Australia’s Michael Blackburn won bronze. Slingsby started thinking about the Athens Games in 2004, and at home that night he jotted down how he would get there: the club trophy in Gosford, followed by the Central Coast championship, a state title, the nationals and then the worlds. After winning Olympic gold, there was the America’s Cup. He taped the list to his bedroom wall, eye level to the bed. “I’ve always been goal-orientated,” he says. “I had to see it every day.”

Otherwise, he kept his ambitions to himself: “I was coming in 10th in the junior race at the Gosford Sailing Club, so I would have been a bit embarrassed … to say out loud what I was thinking.” He trained hard, applying himself morning and night, just as he had with tennis. He came 63rd in his first outing at the nationals; within a year, he was best in his age group.

Back then, Australia sent only one sailor to the Olympics per class and Blackburn had a mortgage on the Laser spot. But if Slingsby could crack the world top 10, governing body Australian Sailing would fund his training and travel. He’d wanted to leave school early but his father, David, insisted he matriculate, which he grudgingly did. An indifferent student, he had never seen the point of higher education.

David got him a night shift behind the bar at the Gosford Sailing Club, and by his 18th birthday he was also holding down a day job at a local boat-building factory, rising at 5am to steal a few hours on the water or at the gym. By now, he was sailing Lasers in the open class. At the 2003 world titles in Spain, he finished 32nd.

His dad decided it was time to face reality. Sorry, mate, you’ll have to do something else, he told his crestfallen son. Slingsby agreed: he would try university if he didn’t make the cut for Athens or failed to secure a lifeline from Australian Sailing. But could he defer uni to have one last crack at the next worlds in Turkey?

This was it. Now or never. Slingsby had sold his own Laser to raise the cash to travel to Bodrum, on Turkey’s Aegean coast. The calculus was brutally simple: without a top 10 finish he was done. On the penultimate day of the 2004 championships he was placed a hopeless 22nd. That night, he headed out for drinks to say goodbye to his sailing friends. “I said, ‘Well, this is my final event. I’ve got no boat at home and no more money.’”

Yet in the cold light of the morning-after something clicked. In the final three races he achieved a first and third, jumping to 7th in the standings. Within 12 months he was top three and in a position to devote himself full-time to the sport. He won his first world title in the Lasers in 2007, backed up in 2008, and entered the Olympic Games in Beijing as the favourite for gold. But there was more trouble ahead. Wind conditions on the Qingdao sailing course were notoriously light, and Slingsby had no more liking for the slow-going than he does now. He decided to shed weight from his rangy 87kg frame by starving himself. When he dropped 10kg the doctors declared enough, but he kept going, bottoming out at 73kg. Inevitably, he fell ill.

The supplied boat wasn’t right, either. Lasers are supposed to be 58kg fully rigged but they can come in a kilo or so either side of that, and the one he got was heavy. The rake of the mast irked him. You get the picture. Even when the wind did blow, he was out of sorts and finished in 22nd place. “I choked mentally and I choked from a sporting point of view. I made stupid decisions that I usually didn’t make,” he says.

There’s a photo of him, slumped in the boat after a race, that vividly captured his dejection. He returned home at a loss once again about what to do with his life. The Olympics were supposed to be his ticket to the big time of the America’s Cup or Volvo Ocean Race where you could make an actual living out of sailing. He was 23 with no medal, no job, no plan.

As it turned out, his friend Nathan Outteridge had also had a disappointing Games. He had gold for the taking in the double-handed 49ers but blew it on the finish line of the final race, capsizing the boat with partner Ben Austin. “Tom and I ended up back home in Gosford and we sulked around together for about six months,” Outteridge says.

“He was heartbroken, I was heartbroken,” adds Slingsby. They decided this couldn’t go on; they needed to do something engaging, anything to get them out of bed in the morning. So the pair went sailing just for the fun of it. The world titles in the A-Class catamarans were coming up in nearby Lake Macquarie, and they gave that a go, finishing well off the pace among the 18-footers. The sky didn’t fall in.

Someone then presented Outteridge with a sailing Moth to try out and both were hooked on the hydrofoiling dinghy. A way forward began to glimmer for Slingsby. “I said to myself, ‘I’m going to do things differently’. Until then, if I had a weakness like light air sailing I’d kind of ignore it. I’d ignore whatever anyone told me to do and bulldoze my way through. I decided that I’d make my weaknesses my obsessions. I’d work and work on them until they weren’t going to cost me another race.”

And he listened attentively to what his new coach, Michael Blackburn, had to say about being professional. How he had to turn up on time, eat better, train smarter. If he was going to succeed in the Lasers, he had to learn everything there was to know about them so he’d never again be thrown by drawing a dud boat. They put the word out that Slingsby wanted to sail the slowest, most cumbersome Lasers around and master them in all conditions.

He started to win again: two additional world titles in the Lasers, and an Etchells class World Championship under John Bertrand, the man who famously skippered Australia II to victory in the 1983 America’s Cup. Slingsby was named the men’s World Sailor of the Year in 2010 and would go to another Olympics, London 2012, the raging favourite in the Laser class. This time, there would be no denying him.

Don’t let your conscience fail you

Just do the stroke

Don’t you take no chances

Keep your eye on top

Do your fancy dances … you can’t stop.

Slingsby is letting rip at the pre-race press conference beneath the striking metallic dome of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, a franchise of the Paris museum. He’s challenging SailGP’s next-gen drivers to lift their game now that Ben Ainslie, 47, has stepped into a coaching role and 44-year-old Jimmy Spithill is using his enforced break to pull together a new team from Italy for next season. Let’s just say it’s not going to make him any new friends. “Jimmy and Ben were third and fourth in the standings when they left [and] I considered those two as my biggest rivals to win the championship each year,” Slingsby tells the assembled media. “To be frankly honest, I think a lot of the younger generation haven’t stepped up to the plate as much as they could have and they’ve got … to show why they’re the next generation of this fleet. I’m the oldest skipper in this fleet. I guess I’m throwing down the gauntlet … if you’re the next generation, you’ve got to prove why you’re the best in the world and knock us old guys off

the perch.”

Fighting words – which Slingsby would have cause to regret before the show moved on from the UAE capital, bound for Sydney. Racing typically takes place over a weekend: three qualifying heats on the Saturday and two more races on Sunday where points are awarded on a sliding scale of 10, depending on where each boat finishes. The top three go through to the event final, a dress rehearsal for what comes at the end of the season on San Francisco Bay. There, the three teams with the highest accrued scores contest the winner-take-all season decider.

People are still talking about last year’s showdown between Burling’s Kiwis – who else? – and the Australians. It all came down to a few moments of heartstopping drama on the finish line. Slingsby appeared to have the silverware and $1.4 million prize in the bag for the third successive time when the Australians’ F50 crashed off its foils heading into the last “corner” of the course, another term borrowed from Formula 1. “I thought, ‘Oh no, this is going to be the biggest choke of all time’,” he says.

Team NZ flew past them, with the British under Ainslie out of contention. But the Australians, digging deep, chased down the New Zealanders to win by barely six seconds. No guesses who the crowd was cheering for.

“A couple of metres at the end was all there was in it – pretty tough for us,” says Burling, who admits the last-gasp defeat still hurts. He and Slingsby first raced against each other for the 2017 America’s Cup, and have been going at it ever since. It’s a chapter of the Australian’s life that hinged off the London Olympics, propelling him into the orbit of tech billionaire Larry Ellison, founder of software giant Oracle, and his partner Russell Coutts, the NZ sailing guru who channelled Ellison’s passion for the sport into SailGP.

At the time, in late 2012, Spithill was heading up Oracle Team USA’s defence of the America’s Cup. He invited Slingsby to come aboard on $8000 a month. The young man hesitated. Bertrand, by now a key mentor, advised him to demand double the pay. Spithill pushed back: If you don’t like what’s on offer, we’ll find someone else, he said. Slingsby took the deal.

The point is, his journey has never been a lone-handed effort. Neither life nor sailing is like that. Slingsby became part of the biggest turnaround in the race’s history, coming back from 8-1 down to see off the Kiwi challenge. “Bugger,” then PM John Key tweeted.

He went on to the 2017 cup campaign, this time in a leadership role as tactician for the American crew. In between, he skippered Anthony Bell’s supermaxi Perpetual Loyal to line honours in the 2016 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race in record time, the best of his six outings in the bluewater classic. He received his second World Sailor of the Year award in 2021 and made it a three-peat in 2023, one behind Ainslie’s haul of four. Burling has two (jointly with Blair Tuke in 2015 and individually in 2017, after exacting sweet revenge on Oracle Team USA in the cup final), while Spithill and Coutts claimed the prestigious award in 2014 and 1995 respectively. You’d better believe they keep count.

Slingsby remembers apologising to Ellison over the 2017 America’s Cup loss – “We made mistakes, and I was owning them” – only to be told not to sweat it. The businessman and Coutts had been talking at length about setting up a new competition, one that wasn’t tied to the cycles of the Olympics or the cup, where they could do things their way. Slingsby was among the first to sign on to SailGP for the tour’s 2019 launch. The 2020-21 program had to be abandoned when Covid struck, but has since found its groove. This season’s calendar reads like a wishlist of international destinations: Chicago, Los Angeles, Saint Tropez, Taranto, Cadiz, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Sydney, Christchurch, Bermuda, Halifax, New York and San Francisco. The expense must be eye-watering.

Each team packs their F50 and gear into four shipping containers that are slung together on land to create a compound: the Australians’ mobile base sports a supersized boxing kangaroo and floor-to-ceiling motifs designed by Slingsby. On race days, dance music shakes the temporary grandstands and hospitality suites lining the course; spectator boats are packed.

Slingsby admits sailing purists have taken umbrage to the brash new format but they’ll come around, and more importantly a whole new audience is being introduced to the sport. “The traditionalists don’t like this type of racing, they say we’re not real sailors,” he says. “But that’s just not the case. We might call ourselves drivers or talk about making a turn or taking a corner instead of tacking but it’s all the same thing. It comes down to wind and water tactics, putting yourself in the right position to win.”

Despite a bust in Abu Dhabi – the Australians won a heat but never really got going in the light air, missing the final – they remain atop the leader’s board on 56 points, followed by Burling’s New Zealanders on 50, in striking distance of catching them in Sydney. The rebooted US team is level-pegging with the Danes on 43 points and Team Spain is in fifth place. Worryingly for Slingsby, his crew is yet to take out an event this year, though their consistency in placing highly has kept them in the hunt.

Could he have been wrong to light that fire under the younger drivers? No fear. “I just felt like I had to do it,” he says. “No one in the world is more competitive than me. I’ll fight for every millimetre around the race track … it’s just my nature and I guess I expect the other guys to think the same way I do.

“A lot of people are saying, ‘Oh, a new generation is coming through’, and that Ben and Jimmy going was part of that. But it’s not true. Ben and Jimmy stepped away on their own accord – they weren’t forced out. And I guess my comments were a bit of frustration about some of the younger guys thinking that they were the ones who did this, getting sort of pumped by everyone around them saying, ‘You’re the next big thing’ when, to me, they haven’t proven themselves yet.”

Come what may, Slingsby is determined to enjoy himself this weekend. His friends and family will be harbour-side for the event, along with Helena, 28, and little Leo, who arrived a few days before Christmas. Talk about a reality check. Slingsby had been sitting out the pandemic in Sydney in 2019 when his bride-to-be appeared on The Bachelor, a TV show he loved; his then flatmate dared him to direct message her. He had a drink or two and pushed send. To his astonishment, Helena messaged back.

The three of them are moving to Barcelona, where Slingsby will be based for the 37th America’s Cup regatta to be contested from August to October. He’s co-helm of the New York Yacht Club-backed challenger American Magic, and this time hopes to get one over Burling in Emirates Team New Zealand, the defending cup holder. Who knows, they might also square off in the SailGP grand final beneath San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge on July 13-14.

Slingsby doesn’t want to think that far ahead. He’s living in the here and now, taking it one race at a time, relishing every moment because he knows that this might be as good as sailing gets for him. “I’m just going to soak it all in. I’m doing what I love,” he says. “I’m doing it with some of my best friends in the world and I’m doing it with an amazingly supportive family. You really can’t beat that.” b

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout