Tide turns on assisted dying laws

In Victoria, more than 200 terminally ill people have chosen to die under voluntary euthanasia laws. Around the country, the tide of sentiment is turning.

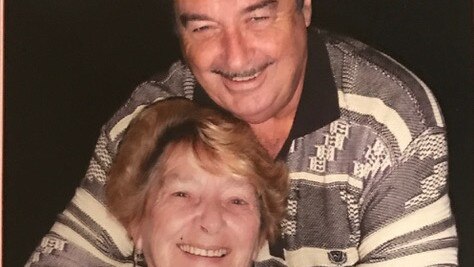

Any day now, a locked box containing a fatal drug dose will be delivered to Betty Licenblat’s home in Melbourne’s south-eastern suburbs. Before long, she will gather her beloved family around her, say her goodbyes and end her life. Licenblat, 77, is dying of pancreatic cancer. Two months ago she was running her fashion and homewares store on Phillip Island and playing bowls at her local club. Now, lying back in an armchair, gazing out at her sun-filled garden, she can barely raise her head unaided.

She’s smiling, though, when we talk in mid-March, serene and sure about the path ahead. It’s not fear of a protracted, painful end of life that has spurred her decision. Rather, as she explains: “I can’t do anything for myself any more. I can see my body deteriorating every day. I’ve lived a full, wonderful life, so I’m not sad about dying. But my mind is clear and I know what I want. I want to be in control; I want to die with dignity.”

Licenblat fulfilled her wish, dying peacefully at home five days after we spoke. She joined a growing number of terminally ill Victorians – 224 people as of December 31 – choosing a voluntary assisted death, under a law in effect since June 2019. From July, a similar option will be available to West Australians; Tasmania will follow mid-next year, while South Australia and then Queensland are close behind. NSW is travelling the same route.

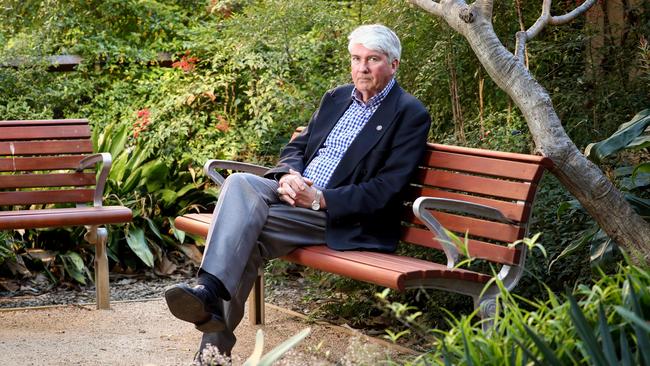

A quarter of a century after Federal Parliament revoked the Northern Territory’s world-first voluntary euthanasia law, the political tide is turning. “It’s an issue whose time has come,” says West Australian Premier Mark McGowan. To date, warnings that the Victorian law could be abused – by “impatient inheritors” coercing elderly relatives, for instance – have not been realised. On the contrary, says former Supreme Court judge Betty King, who chairs the Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board, “a really consistent theme has been the reluctance of families, who don’t want their parents to die”. According to the board, nearly 100 Victorians who were dispensed the medication in the first 18 months ended up not taking it – confirming a widely held theory that just having the drug at home can allay people’s anxieties and improve their quality of life. Retired Melbourne accountant Bob Pitts, who had prostate cancer, told me in late February: “It’s an insurance policy and I may never cash it in, but it’s there if I need it.” Pitts died three weeks later, without taking the medication.

For some, however, that reassurance remains frustratingly out of reach, thanks to a legal framework described by Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews as “the safest and most conservative in the world”. Critics say a mandatory prognosis of less than six months to live (12 months for neurodegenerative diseases) is excluding people whose chronic conditions are causing grievous suffering, while a shortage of willing doctors has, at times, prolonged or even obstructed the assessment process.

As adversaries prepare for fresh battles around the country, terminally ill Australians are running out of time. “I know what’s to come, and it terrifies me,” says Tanya Battell, who lives in Brisbane and has metastatic breast cancer. “It’s 2021 and there are kinder ways to die. It shouldn’t be determined by your bloody postcode.”

For decades, doctors have smoothed the passage of the dying, administering increasing doses of morphine to induce a coma-like state. While the practice is legal if the goal is to alleviate symptoms, some physicians, such as West Australian GP Alida Lancee, admit to having employed it to expedite death. “I couldn’t watch my patients needlessly suffering,” she says. “Some of my colleagues felt the same, but many didn’t provide this relief, for fear of prosecution or [because of] their religious beliefs.”

Just four people, assisted by Darwin doctor Philip Nitschke, used the NT’s law before federal Liberal MP Kevin Andrews led a push in 1997 to have it repealed. “Andrews bragged he’d set the movement back 20 years, and at the time I thought it was a hopelessly overstated claim,” says Nitschke, whose “death machine”, a laptop computer linked to a syringe driver, is now on display in London’s Science Museum. “As it turned out, he was quite correct.” The long interregnum was not for want of effort; dozens of private members’ bills were tabled in state parliaments during those years. Despite polls consistently showing more than 70 per cent support, all of them failed.

In 2016, the year broadcaster Andrew Denton created his Go Gentle lobby group, members of a subsequent Victorian parliamentary inquiry travelled to Switzerland, the Netherlands, Canada and the US state of Oregon. They returned convinced that the horror stories – mobile death vans, elderly and disabled people badgered to die, depressed teenagers ending their lives on a whim – were unfounded, and that safe and effective laws could be designed. At home, it was as if a reservoir of sorrow had burst. The inquiry was told of agonising deaths scorched into loved ones’ memories, of people starving themselves to accelerate the dying process, and of suicides. Terminally ill Victorians, the State Coroner testified, were hanging, shooting, gassing and poisoning themselves at a rate of about one a week. In one documented case, a 90-year-old man ended his life with a nail gun.

The inquiry report, recommending government-sponsored legislation and a conscience vote, might have been consigned to a shelf in the parliamentary library. Earlier that year, however, Premier Daniel Andrews – a Catholic who had previously opposed assisted dying laws – had lost his own father, Bob, to cancer. Bob had faded to a shadow of the “big person” his family had known, Andrews told The Sunday Age, and he realised “our laws needed to change”. That switch of heart was “absolutely critical”, says Victoria’s then health minister, Jill Hennessy, herself passionately pro-reform, having witnessed her mother’s devastating decline from multiple sclerosis.

Striving to address MPs’ apprehensions, Hennessy felt at times “an unbearable sense of responsibility”, she recalls. Church leaders denounced the bill from the pulpit and in the corridors of power; sympathetic Liberal MPs faced threats of hostile preferencing and disendorsement. Electorate-level polling by Go Gentle, meanwhile, revealed support spanning all demographics, including conservative and religious voters. The Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill, with its 68 safeguards and an 18-month implementation phase, passed in Victoria on November 29, 2017.

On July 15, 2019, with her daughters Jacqui and Nicole beside her, Kerry Robertson, 61, swallowed a solution containing pentobarbital, a powerful barbiturate. As she slipped away in her Bendigo nursing home, “you could see all the pain disappear from her face… it was beautiful and cathartic and peaceful”, says Nicole.

Consumed by metastatic breast cancer, her “sparkly blue eyes” dulled to grey, Robertson had been racked with pain so severe that, according to Jacqui, “if you tried to touch her arm, it was just excruciating”. She was the first person to use the new law, which is open to Victorian adults of sound mind with an incurable illness, the necessary prognosis and “intolerable” suffering. She had been assessed by two doctors, one a specialist, and made three separate voluntary requests, including a written declaration.

Denise Keeshan was an extrovert 76-year-old who loved red wine and a gossip, and ran the TattsLotto syndicate at her Melbourne retirement village. By August 2019, cancer had shrunk her to 35kg. Her son, Anthony, found the prospect of her assisted death “very confronting”, he says. “But when I put myself in mum’s shoes, I got it. She didn’t want to go out ugly, just withering away, becoming horribly sick.” Seated in her electric armchair, a blanket pulled up against the cold, Keeshan enjoyed a final glass of wine and a McDonald’s strawberry sundae. “Mum was never more at peace than that day,” Anthony says. “There were lots of tears, and some laughs, and lots of love in the room. And when the time came, she just grabbed the cup and threw it down. It was tough, but she went out on her own terms and I’ve got nothing but respect for her for that.”

Keith English, 190cm tall and with a personality to match, relished provoking a lively debate. “Who do you think are stronger, men or women?” he demanded of the two female pharmacists who delivered his lethal medication. English, 96, chose to have just his daughter, Marita Scott, with him at the end. “He wanted quiet, he wanted calm, he didn’t want an audience,” says Scott. On September 16, 2019, she took her father for a drive around Port Phillip Bay, then that night, by an open fire, he shared a light supper – a prawn and mango salad – with Joyce, his wife of 68 years. Their “last date”, Joyce called it. The next morning, English re-read letters he had penned to his five children and nine grandchildren, before venturing out to feel the sun on his face. And shortly after 11am, to the strains of Amazing Grace, Keith English drew his last breath.

Cameron McLaren, a Melbourne oncologist, has observed 43 assisted deaths; doctors are often asked to attend, and can administer drugs intravenously to patients unable to swallow. McLaren arrived at one man’s home to discover a party in full swing, with about 200 guests, “speakers set up, music blaring and beer cans everywhere”. At 2pm, he recounts, “the patient went into his woodworking shed, lay on his work bench, took the medication and passed away with his wife and his best mates with him”.

Rather than unmanageable pain, the impetus for those accessing the law – the vast majority late-stage cancer patients – is usually what doctors term “existential suffering”. As people lose function, independence and joy, they yearn, above all, to regain a sense of control. Former judge Betty King notes: “They can’t stop the disease, they can’t stop what’s ravaging their bodies, but they can say, ‘From now on I will control what happens to me’.”

On state election day in 2017, Clive Deverall, the former head of WA’s Cancer Council, took his life in a Perth park. The timing and public nature of his death, together with a note he left stating “Suicide is legal, euthanasia is not”, sent an unambiguous message to Mark McGowan’s incoming Labor government. Plagued by a host of serious illnesses, Deverall, 75, had been an outspoken proponent of voluntary euthanasia. He had also championed palliative care, the branch of medicine devoted to relieving end-of-life symptoms, while recognising its limitations. “Clive always said there was a small percentage of ‘palliative care nightmares’: people who cannot be helped,” says his wife, Noreen Fynn.

The new premier was receptive – and whereas in the past the politics might have seemed too hard to crack, “Victoria had shown there was a way forward”, acknowledges McGowan. His health minister, Roger Cook, met with Fynn, who had shouldered her husband’s advocacy role. “I was blown away by her strength and courage, and I thought we owed it to her to give it a red hot go,” Cook tells The Weekend Australian Magazine.

On August 6, 2019, the day before a government bill was to be introduced, Perth law graduate Belinda Teh arrived at Parliament House, completing a 70-day walk from state parliament in Melbourne that signalled her resolve to bring Victoria’s law home. Telegenic and articulate, Teh, 27, became the face of a campaign uniting doctors and nurses, grief-stricken families and dying West Australians such as physician Colin Clarke, who spent precious last moments lobbying MPs and addressing rallies before dying last year aged 45. “The WA community raised their voices, and they never stopped raising them,” marvels Teh, whose mother, Mareia, endured horrifying pain, “twitching and shaking and rasping for air”, and entreating doctors to hasten her death, before succumbing to cancer in 2016.

Mareia’s was a “nightmare” case; so was that of Busselton man Russell Quinlivan, a keen surfer reduced by lung cancer to “a skeleton on the bed, moaning and grimacing, racked by electrifying pain”, as his wife, Peta, describes it. Another campaign recruit, she shows me photos of Russell before he became ill: fit, tanned, handsome.

WA’s law, passed on December 10, 2019, is soon to come into force; Perth retiree Brian Sayer* is already sounding out doctors. Recently diagnosed with Stage 4 lymphoma, Sayer, 73, who had been playing sport twice weekly, can barely walk a few metres now. He wants his family “to remember me as I am, not as I will be if things get worse”.

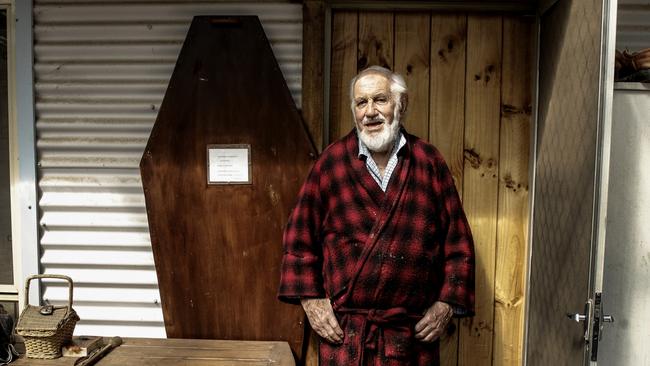

It’s a surreal situation: two men sitting around a Formica table in a modest timber house with a fruit-laden pear tree out front, discussing end of life options. The house in Creswick, in gently rolling countryside north of Ballarat, belongs to mild-mannered 88-year-old Geoff Rawson, and his visitor is Rodney Syme, a retired doctor and veteran of the voluntary euthanasia movement. For years, Syme openly flouted the law against aiding a suicide, supplying pentobarbital to hundreds of patients and challenging authorities to prosecute him (they never did).

Rawson has inoperable bladder cancer. His symptoms are distressing: he has to urinate very frequently, expelling large blood clots, and he recently needed multiple blood transfusions. While he still enjoys building furniture and playing croquet, what he calls his “good life” is fast diminishing, and he wants the escape hatch of pentobarbital in the cupboard. He has not yet succeeded in securing a six-month prognosis, however, and is afraid of his disease’s inevitable “nasty” progress. So Rawson is formulating back-up plans. Instructions for his funeral are pinned up on a wall. He has even made his own coffin, although for now it is propped up in his living room, serving – with the addition of some shelves – as a display cabinet.

To Syme, Rawson exemplifies a “profound flaw” in the Victorian safeguards. “For God’s sake, this is about relieving suffering,” he exclaims. “There are people with two or five years to live who have terrible, untreatable chronic pain. This is leaving a lot of people out in the cold.” Philip Nitschke says, scornfully, of the law: “You’ve got to be damn near dead to be eligible.” As Jill Hennessy sees it, “whenever you make a law you draw a line, and people are going to fall either side of it”.

Advocates such as Marshall Perron, the Northern Territory’s former chief minister and architect of its landmark legislation, had hoped eligibility would be based on death being “reasonably foreseeable”, as in Canada, or on intolerable, untreatable suffering, as in Belgium and the Netherlands. But neither criterion has proved politically palatable in Australia. WA and Tasmania will stipulate a six-month prognosis, although – unlike in Victoria – doctors will be permitted to raise the subject of assisted death, and patients will not require a specialist appraisal. In Victoria, a scarcity of amenable specialists, particularly outside Melbourne, has led to some people dying before they could complete the process.

Kristin Cornell spent three months last year searching for two specialists in Geelong to assess her father, Allan, crippled by motor neurone disease. To Kristin, an obstetrician, it felt like “trying to get a backyard abortion”. She relates how Allan, a former farmer, wept on learning of yet another delay, later begging her: “Where’s the bloody tablets, Kristin? I can’t do this anymore.” His last-minute assisted death was “not peaceful” and, his daughter is certain, “the only reason it happened at all is that I’m a doctor, and I pushed and pushed”.

The Australian Medical Association has campaigned vociferously against assisted dying, yet the profession – including the AMA itself – is deeply divided. Former president Brian Owler chaired the expert panel that drafted Victoria’s legislation; his successor, Michael Gannon, inveighed against the law. After Victorian ministers told their stories of personal loss, Gannon tweeted: “Don’t forever alter society ‘coz few powerful people see parent die.”

Doctors with religious or ethical qualms can “conscientiously object” to participating in the scheme. Emergency physician Stephen Parnis is one such doctor. Branding Australia’s new laws “a jump off the cliff into the unknown in a hell of a hurry”, he deems the risks – of vulnerable people being coerced, and of “the significant likelihood of wrongful death” resulting from a flawed diagnosis or a failure to identify a patient with depression – to outweigh any benefits. Parnis is a Catholic, but insists his views are rooted in medical ethics rather than religion. “It’s that notion of ‘first, do no harm’,” he says. “To my mind, killing a patient, or giving them the means to kill themselves, is the ultimate in harm.” Inner-city GP Nick Carr disagrees. “I’ve been to a lot of lousy deaths, and to say to patients at the end of their lives, ‘Sorry, I can’t help you’, that’s harm to me.”

Phillip Parente, a senior oncologist and devout Catholic, expected to be a conscientious objector. But the first time one of his patients requested an assisted death, his outlook changed. “To refer them on felt like I would be abandoning them at the time of their most courageous decision,” he explains. “It would be traumatising and stigmatising for them, and I couldn’t reconcile that with my ethos as a doctor.” Parente has since assessed about a dozen patients. “I feel honoured to be part of their journey. And really I can’t see anything in the Catholic doctrine that prevents me from helping them.”

Frank Brennan, the Jesuit priest and law professor, fears the right of conscientious objection – which also applies to healthcare institutions – will be watered down over time. He is concerned, too, that “euthanasia could become a shortcut” in remote areas with poor palliative care. “For centuries, ‘Do not harm and do not kill’ was a clear line, and people knew what it meant,” he says. “As a society we’ve now departed from that, and there’s no other line with equal clarity or depth.”

When Tasmanian Diane Gray was dying of cancer in 2019, “in constant pain”, a story about Victorian Kerry Robertson’s assisted death came on the TV news. “I looked at Mum and she had tears rolling down her face,” recounts her daughter Jacqui. “She said, ‘This is what I desperately want’.” That year, independent MP Mike Gaffney embarked on a solo endeavour to reform Tasmania’s law. At community forums he played a recording of Gray’s final journal entry, in which she wrote that “every bit of life has been torn away from me”. Gaffney’s legislation passed in March this year, the first such private member’s bill to succeed.

South Australians hope they will be next; a private member’s bill on assisted dying, the 17th attempted in the state, was passed by the Legislative Council on May 5 and will go to the Lower House for a final vote. Queensland is set to table government legislation later this month, while in NSW, independent Alex Greenwich plans to introduce a bill in September. Although NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian is reportedly reluctant to take on religious conservatives in her own party, proponents point to decisive election wins in Victoria and WA as burying the notion that the issue is political poison. Meanwhile, the Territories are clamouring for their right to legislate on assisted dying – stripped under the 1997 federal law – to be restored. “It’s frustrating to see what’s happening around Australia while we’re treated as second-class citizens,” says Tara Cheyne, the ACT’s Minister for Human Rights. “People are asking, ‘Why don’t we have voluntary assisted dying?’ – and they’re horrified that we can’t decide this for ourselves.”

As they wait impatiently for their own laws, terminally ill Australians are hatching plans to travel to Switzerland, Covid-19 restrictions permitting. They are illegally importing pentobarbital or hoarding prescription drugs, aware they must die alone or risk criminally implicating loved ones. Lawrie Daniel made sure his wife, Rebecca, and two children were out before taking his life in their Blue Mountains home in 2016. Lawrie, 51, who had multiple sclerosis, had unrelenting pain, Rebecca says, and was “terrified of losing all movement, because his uncle [who had MS] couldn’t shoo a fly away at the end”. Lawrie’s death, she contends, “wasn’t suicide, it was voluntary euthanasia: a very rational, thought-out act. But he was alone and he didn’t get to say a proper goodbye.”

Former NT chief minister Marshall Perron is not surprised the states are finally coming on board at a time when Baby Boomers are “starting to consider their mortality”. Australia’s most effective assisted dying law, Perron argues, will be “the one that affords the most generous access, providing it’s voluntary and the safeguards are there”.

Most likely, though, assisted dying will only ever account for a tiny percentage of Australian deaths. In Oregon, where a similar law has operated for more than 20 years, the figure is less than 0.5 per cent. And most Oregonians, like most Victorians, take the medication in their final weeks of life. As retired doctor Rodney Syme observes: “People want to live. That’s what my experience has taught me.”

* Name has been changed. Lifeline: 13 11 14

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout