These men are conquering crypto — but are the stakes too high?

Virtually unnoticed, they went from teenage gamers to making as much money as supermarket giant Coles by creating the world’s biggest online casino. For the first time, they reveal how they did it.

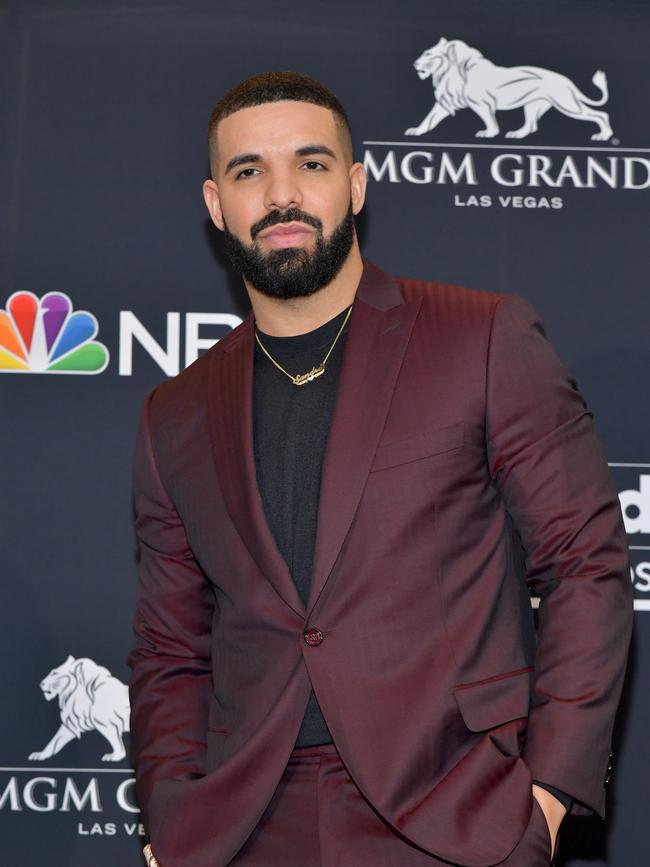

Hip-hop superstar Drake, who has 170m record sales and 122m Instagram followers, has just put down a $US944,000 ($1.5m) bet in cryptocurrency on a virtual roulette table manned by a cartoon croupier. It’s another big night online for Drake – a prolific gambler best known for songs like Hotline Bling and Child’s Play – who is streaming his betting on Twitch, millions of fans watching his every move. While Drake is famous worldwide, the young man he enthusiastically calls “Eddie” on the other end of a phone watching the rapper’s huge bet is not. But Eddie is making more money and running a business that has had more success at such an early stage than just about anyone else in Australian history.

Eddie is Ed Craven, 27, a little-known Melburnian who is among the world’s youngest self-made billionaires and who, with business partner Bijan Tehrani, 28, has quietly built what they say is the biggest gambling website in the world, Stake.com. Their story started with a friendship forged via the internet from opposite sides of the world and moved from capers as teenage gamers to trading huge sums in the largely uncharted world of cryptocurrency and unregulated online gambling. Now it’s culminating in a quest to transition to a more established mainstream business, albeit one that will remain in their private hands.

Documentation seen by The Weekend Australian Magazine shows that Stake customers around the world bet an average $US400m ($590m) each day using cryptocurrency – although none of it in Australia, where online casinos are banned. The business is set to crack $1bn in profits this year – as much money as supermarket giant Coles makes and three times the earnings of the privately held Chemist Warehouse last year. All this happens from an old bank building in Melbourne’s CBD, where the art deco-inspired exterior houses a cutting-edge office that looks like something out of Silicon Valley inside: dark walls, neon signs, a table tennis table, free food and a bike rack mounted to the wall.

Until now, no one in Australia has had any real idea of just how big and profitable Stake is and Craven had never spoken publicly. Craven burst into the headlines this year when he shelled out $88m for a “ghost mansion” in Melbourne’s Toorak, a few months after paying $38.5m for a nearby house months earlier. At the time, the only picture of Craven – who grew up in Coffs Harbour – to be found online was one of him enjoying a chicken parmigiana at a pub with workmates.

Even less has been written about how US-born Tehrani and Craven met during high school on a popular fantasy dragon-slaying website, got busted operating an illegal casino within the game, parlayed that experience into a cryptocurrency-friendly dice game, survived a $1m hack attack and death threats. In recent months, the pair have found themselves facing a $US400m lawsuit from a former business partner. Yet, in just a few years, they have managed to build Stake into a massive venture.

Somehow, Drake has become a part of all this. While he lives the party lifestyle one would expect of a wealthy rapper, Craven and Tehrani are shy, softly spoken and usually wear black hoodies, jeans and sneakers – the poster tech bro look. The Canadian superstar and Craven speak every day. Stake signed an endorsement deal with Drake in March that included the rapper streaming his gambling sessions live on Twitch.

“You got me sweating!” shouts Craven down the line to Drake as the pair watch the roulette wheel spin that will decide the rapper’s $1.4m bet on his lucky number 11. Drake is sitting next to fellow rapper French Montana, and the stream shows he has almost $US12m in his betting account. The pair dissolve into laughter when number 11 comes up, winning Drake another $US9m. “Sorry Eddie!” Drake screams in delight.

In reality, it is Craven and Tehrani who are winning big. Stake has taken about 110 billion bets since its inception only five years ago. All the bets are shown online; a chat function will often have more than 20,000 punters eagerly showing off their winning bets and waiting for free money to “rain” down on them from big gamblers. In May, Drake handed out $US1m worth of Bitcoin to followers to bet during a live Twitch stream. All those bets are being waged by punters playing about 3000 casino games such as slot machines, baccarat, blackjack and roulette, and betting on more than one million sports matches globally each year on their computers and phones using cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Dogecoin.

So big is Stake that its owners claim it accounts for about 7 per cent of total Bitcoin transactions around the world daily (blockchain.com statistics show there are usually 200,000 to 300,000 Bitcoin transactions per day). “People have been trying to find the killer application for cryptocurrency,” says Tehrani. “Well, it’s gambling.”

Of course, Stake isn’t exactly a straightforward business. It is regulated through the tax haven of Curacao in the Caribbean and operates mostly in so-called “grey” or pre-regulation markets – that is, those that have yet to ban or allow online casino gambling or punting with cryptocurrency.

In September, Craven and Tehrani were hit with a $580m lawsuit in New York from a former associate, Tehrani’s best friend in high school, who claims the pair cut him out of the business before it went on to become a success. Christopher Freeman alleged Tehrani “bullied” him and that he was misled into not participating in the formation of Stake in 2017 after being involved in their previous businesses. The Stake founders say Freeman’s court action is “utterly frivolous” and “provably false” and will defend the case.

Stake’s profits are enormous, even if the amount they make from each bet is a lot less than long-established betting companies such as Tabcorp (owner of the TAB in Australia) and big overseas firms like Bet365. Stake’s profit margin is about one per cent, they say – but it takes big bets. For example, Drake – one of 300 big-time gamblers in Stake’s VIP program – lost more than $20m during that one live gambling session stream in May.

Craven and Tehrani’s company claims a net profit of more than $1bn in the year to June 30, 2022, up from about $520m in 2021. The pair have become very rich, very quickly. Based on the size of publicly listed gambling companies, Stake could be worth more than $5bn now – which would make Craven easily the wealthiest 20-something Australian. However, Craven and Tehrani remain virtually unknown in Australia. Online casino games are banned here, as is gambling with cryptocurrency; they are also banned in the US, and Germany cracked down earlier this year. But an average of more than 700,000 customers in Canada, Brazil, the Philippines, parts of Europe, Asia and elsewhere gamble on Stake’s website every day.

In recent weeks, Twitch banned streaming live gambling on its platform. The development highlights the wildly unpredictable environment Stake is operating in. Undeterred, Stake is extending the endorsement contract with Drake into 2023 so the rapper can promote the firm via his other social accounts. In late September, Stake’s own Instagram account carried pictures of Drake with actress Margot Robbie at a party for the release of the movie Amsterdam, featuring Stake casino chips and expensive gift bags.

In a way, Craven and Tehrani have been operating just beyond the reach of authorities ever since they met online as teenagers in high schools on different continents a little over a decade ago. Craven was born in Sydney but his family would later move to Coffs Harbour after his father Jamie had been declared bankrupt and spent six months in jail in the late 1980s over the collapse of the financial group Spedley Securities. Tehrani’s parents moved to the US from Iran as teenagers during the Islamic Revolution in the late 1970s. At one stage his father worked at a 7-Eleven in Texas and his mother lived in a convent in Boston before the pair met at college, married and settled in New Canaan, Connecticut, a town of about 20,000 people an hour’s train ride from Manhattan.

By their early teenage years Craven and Tehrani had discovered computer games – much to their parents’ consternation. “I definitely loved them a bit too much,” says Craven. “Yeah, I was a nerd,” says Tehrani. “If I think about my hobbies in middle school and high school, it was gaming.”

Like the Dungeons & Dragons board game players before them, RuneScape’s medieval looks and knights in shining armour appealed to teenagers, who stormed castles, cast spells, pickpocketed or went on buried treasure quests. “We played the game because we enjoyed it, but then it obviously moved into the fascination of trying to make money off the game,” explains Tehrani. “At that point, one per cent of the people who played the game were trying to get and make money. The rest of them were just killing dragons and stuff.”

RuneScape players earned virtual gold coins. Craven says the pair were probably among the best 50 to 100 players around the world and would compete hard for the coins, which they sold offline for real currency – something the game’s developers frowned upon. That was lucrative enough, but even more of a money-spinner was an online casino of sorts that Tehrani decided to set up in one part of the RuneScape world, enlisting Craven’s help after the pair had been rivals within the game.

Gambling was a big hit on RuneScape and, to their parents’ astonishment, Craven and Tehrani were able to swap enough virtual coins for real money to each make about $100,000. It was enough for Craven to help buy his parents a coffee shop franchise on the Pacific Highway at Coffs Harbour, fulfilling their ambition to run a cafe. “Before then it was something imaginary,” Craven says with a smile. “They called it fairy money. It hadn’t made any sense to them, coming from a 16 or 17-year old kid saying you were collecting these coins that could be sold for real money. From then on, it clicked for them and they were more lenient in letting me play.” RuneScape’s developers didn’t extend the same leniency: in 2011, Craven and Tehrani were banned from the game.

By then, the cryptocurrency Bitcoin was starting to emerge. Invented in about 2009, Bitcoin had a small but enthusiastic following within a couple of years. Tehrani says he and his nerdy friends mined a small amount of Bitcoin themselves – “it was a fun little thing to do, kind of a joke really” – and also dabbled in playing an online game called Satoshi Dice. Players sent Bitcoin to be used as a bet on dice rolls, with wins and losses based on numbers randomly generated via the blockchain.

Tehrani played but found the experience slow and clunky, and decided he could build a better version. He asked Craven to help (though, without telling his business partner, Craven outsourced the programming to a friend) and the pair – who still hadn’t met in person – built their own cryptocurrency dice gambling website called Primedice. “We didn’t really know each other,” says Tehrani. “We were 17 and 18 and both pumped up our ages. Ed was pretending to be older, and I was thinking ‘I don’t want this guy to be older than me’. We both wanted to be taken seriously. When we started talking to each other on voice [online], we’d both try to make our voices sound deeper.”

Tehrani was studying business and economics at Babson College in Boston, keeping his fledgling business secret from friends while his grades suffered. “My dad knew loosely what I was doing and definitely asked me to shut it down several times.”

The pair would pack almost a lifetime’s worth of business ups and downs, near collapses and breakthroughs into the next decade. Primedice launched in 2012, and while it was a fledgling business in a new online world, the pair did employ some old-fashioned business strategies. They kept their profit margins or “house edge” (the mathematical advantage the casino or “house” has) low, returning more to players than other gambling entities they were effectively undercutting. They also gave away free “money” to players to bet with, and incentive to play on their site.

They marketed their new venture via the bitcointalk.org online forum started by Bitcoin founder Satoshi Nakamoto, where Craven and Tehrani would pay the hardcore crypto and blockchain enthusiasts to put Primedice.com banners under their profiles. While those in the know flocked to their new site, it started haemorrhaging money almost immediately, losing the pair between $10,000 and $20,000 per game. But they held their nerve and soon the betting volume was sufficient to make the pair some money. Primedice lumbered along, keeping Craven and Tehrani busy on opposite sides of the world. But the pair were making profits and by September 2014 it had recorded its billionth bet. “It helped that there was nothing to do with Bitcoin back then,” Tehrani says. “There were no established exchanges. People mined it, gambled it and bought drugs with it … but there were limited ways to spend it.”

“My dad knew loosely what I was doing and definitely asked me to shut it down several times.”

Then disaster struck. The pair had established a small team and had just launched an updated third version of Primedice. Almost straight away they noticed some unusual betting activity from two accounts, one that received their payouts and the other cashing out after a delay. The latter waited a few weeks and returned under a new account called Hufflepuff, quickly betting $8000 worth of Bitcoin every second for hours on end. And winning. Eventually the pair discovered Hufflepuff was cheating – the method involved confusing Primedice’s servers into corroborating the outcome of a bet before it was placed. Hufflepuff knew in advance whether they would win or lose and could wager accordingly.

Craven and Tehrani tried to track Hufflepuff down via various crypto gambling forums and demand their money back. Hufflepuff cashed out about 2400 Bitcoin, worth about $1m at the time, and later messaged Craven and Tehrani, saying: “Your demands are laughable … I actually enjoy this shit. Oh, and by the way, there are some pending withdrawals you need to process.” Tehrani says, “Given the nature of Bitcoin, there wasn’t much we could do but take it on the chin.”

From there, Primedice was a success, although it faced more competition as cryptocurrency’s popularity grew. One was a site called Bitsler, made by a Russian Primedice customer. Their rivalry was intense and at one stage Tehrani received a death threat from the customer, who Tehrani says “made himself out to be a Russian gangster … but we weren’t too worried by him.”

By 2016, Tehrani was finishing his college degree and pondering what to do next with Craven. At one point he had ambitions to be a base jumper and moved to California, where he did about 100 skydives. Meanwhile, Craven was in Australia trying to drum up mainstream interest in his “provably fair” technology for online gambling.

The provably fair system is a mathematical method or algorithm that is used to ensure that neither the players nor casinos can know the result of the game before it begins. It uses a seed or digital fingerprint using random numbers generated by the casino and player. In simple terms, the player can see the casino’s seed after betting has taken place to verify the fairness of the result.

Craven says he wrote white papers on the system and tried to patent it, and held meetings with gambling authorities in Queensland and Tasmania. He even suggested regulators could use it on poker machines. “We were very young and naive … We really thought it could revolutionise the physical gaming industry. Nothing eventuated. But I did end up getting an email from the EA [executive assistant] of James Packer, basically saying ‘stay in your lane’ and ‘by the way if you’re ever in Israel, let’s catch up’.” (In an email to The Weekend Australian Magazine, Packer says he doesn’t remember the exchange.)

Tehrani was surprised his business partner had managed to attract the attention of Packer, the biggest shareholder in casino giant Crown Resorts, who was living for spells in Israel. He says it was Packer’s email that gave him the final impetus to travel to Australia to meet Craven for the first time and figure out what they would do next. “At this point I didn’t think Ed really knew what he was doing but I saw that email and if he’s pissing off these billionaires, he’s doing something that is scratching a nerve somewhere. I think it was FOMO [fear of missing out] and so I went down to Australia.”

Tehrani didn’t bother to pack up his apartment in New York, intending to stay in Melbourne for only two weeks. Meanwhile, Craven had rented office space in Melbourne’s CBD and was thinking of doing something bigger than Primedice. They eventually decided on launching an online casino using cryptocurrency only, buying the Stake.com domain name from a California businesswoman, who asked for a 3 per cent shareholding. When Craven and Tehrani couldn’t produce any financial accounts, she sold it to them for $US150,000.

The pair say they sank “several million worth of crypto” into developing Stake, combining casino games with Primedice’s provably fair technology and launching it in 2017. “Honestly, it was a flop,” says Tehrani. He and Craven had tried to combine online adventure gaming with casino games such as roulette and poker, appealing to gamers more than gamblers. It took two years of losing money, and a rejection or two from venture capitalists, but in time Craven and Tehrani would focus on providing casino games and making the website as gambler-friendly as possible. Tehrani says they kept profit margins “absurdly low” and eventually, a big focus on slot machine games had online crypto gamblers flocking to their website. Endorsement deals with the likes of Drake, English soccer clubs Watford and Everton, mixed martial arts circuit UFC and motor racing drivers helped raise Stake’s profile. An explosion in interest in cryptocurrencies boosted the business, and the rapid downturn in value this year – the so-called “crypto winter” – has not slowed Stake’s profits, they claim. Tehrani admits he and Craven have lost some personal wealth held in various currencies but both say they are long-term crypto believers.

More widely, Stake is making a move into more traditional gambling markets. It has applied for a gambling licence this year in the Canadian state of Ontario, which will allow it to offer online casino and sports betting in Canadian dollars. They say they have passed all regulatory processes and could secure a licence by the end of the year. That move, Craven admits, is an acknowledgment that government legislation around the world is tightening. “We work in the pre-regulator market, but regulation is going to become more apparent, like it is in Ontario and in Germany last year. All these countries will slowly want their own regulation and we need to be ready to adapt to that.”

Stake’s owners have their sights set on licences in the US, where several states have allowed digital betting after decades of bans. They want to operate in Australia too – and they aren’t afraid of the competition. “We’re applying for [an Australian licence] now … and hopefully will get it in a year,” says Tehrani. “It will only be sports betting. I think long-term it makes sense; we live here. It’s super competitive but I think it’s 100 times more competitive on the internet [worldwide] … The challenge is operating on low margins. But Ed and I are pretty confident that whatever market we go into, we can make an impact.”

Craven says that Melbourne will remain Stake’s headquarters and that he and Tehrani want to keep the business privately owned. Tehrani plans to become an Australian citizen; he loves Melbourne and wants to bring his family over. Their plans could include a crypto exchange and other service businesses, again using low-fee models, and potentially even a land-based casino. More sponsorships of major sports teams are in the works.

Craven is spending another $150m on transforming the half-built “ghost mansion” he bought for $88m in August. His architect says it will not be a typical Melbourne house but instead take its inspiration from mansions in the Hamptons or Los Angeles. When asked about the house, Craven says he was surprised by the attention the sale got but admits the publicity helped his company.

He has big ambitions for Stake. “The immediate goal is to become the largest betting brand and transcend just being known within the crypto industry, and really make Stake.com pretty much the first thing people think of when they think of online gambling. To really conquer the industry.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout