The trauma that propelled Robyn Davidson into a life of wandering

The Tracks author gave herself to a two-day love-fest with Salman Rushdie, she says, because ‘I thought he would disappear’. But two weeks later she got a letter to say, ‘I’m leaving my wife’.

In a renovated colonial cottage on the main street of a drowsy Victorian Goldfields town, Robyn Davidson the perennial wanderer has put down roots. It’s early spring. The nature strip before the house is woven with African daisies, a showy old pink rose has burst into bloom, and the shade trees are in full leaf. An excitable working dog beside her, Davidson welcomes me at the gate with an engaging smile. “Down boy!” she snaps at her dog, his black coat splashed silver in the afternoon sun. “Down Diggity!”

I cut her a look and in answer to the unspoken question she shrugs. “Yes. It’s Diggity number two.”

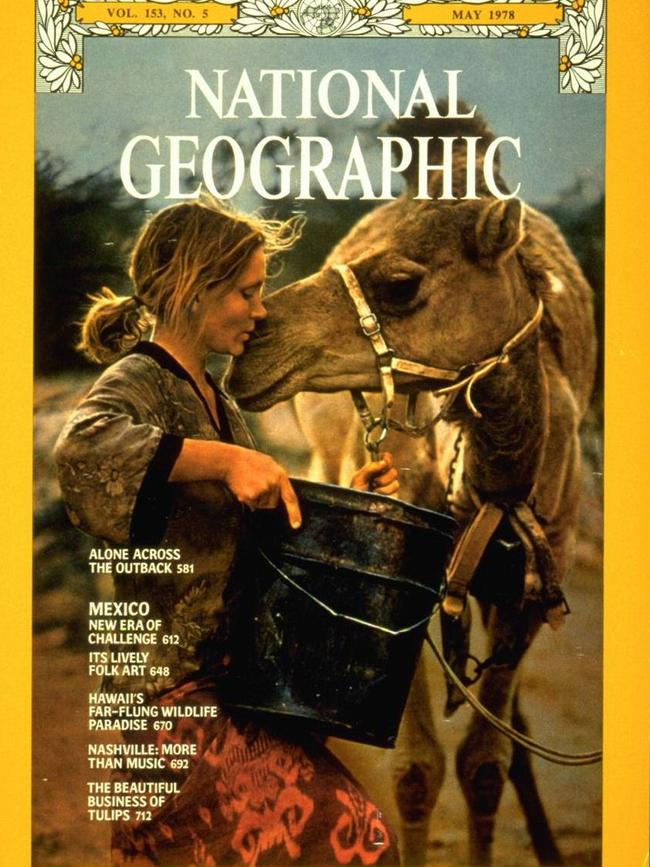

Diggity number one accompanied Davidson for the better part of her famous camel trek from Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean that she worked up into the memoir Tracks. In 1977 she set off with Diggity and four camels – Dookie, Bub, Zeleika and Goliath – on that journey through a harsh yet spectacularly beautiful landscape, a bildungsroman, an awakening, a “self-proving”, in her words. “The assumption has been that it was hard and hot and a struggle and terrifying, but it wasn’t like that. It was a going into something; a being part of something. It was joyous.”

The memorable opening of Tracks still shimmers: I arrived in the Alice at 5am with a dog, six dollars and a small suitcase full of inappropriate clothing… A freezing wind whipped grit down the platform as I stood shivering, holding warm dog flesh, and wondering what foolishness had brought me to this eerie, empty train station in the centre of nowhere… Diggity wriggled out of my arms and looked at me, head cocked, piglet ears flying. I experienced that sinking feeling you get when you know you have conned yourself into doing something difficult and there’s no going back.

The American photographer Rick Smolan, who was shooting for National Geographic, dropped in and out, and an Aboriginal elder named Eddie accompanied her from Pipalyatjara to Warburton in WA: a 300km bite out of the 2700km trek. She admits in that book to a certain “romantic naivety”. She had no intention of writing about the journey afterwards. It was, she tells me, a “deeply private act”.

And yet the article Davidson penned about the trek for National Geographic, followed by a piece for The Sunday Times in London, the 1980 publication of Tracks, and, much later, the film of the book, has given this journey with an inscrutable private purpose – the doing of something just for itself – the most public afterlife imaginable. For more than 40 years Davidson’s bold public identity has managed to shield the sometimes brittle private self – a self that harbours a deep and abiding wound. With the publication of another memoir Unfinished Woman a couple of months ago, much more of that private self is laid bare.

But not all.

The novelist Doris Lessing, whose London house Davidson was sharing in the late 1970s, read Tracks in manuscript and declared it an instant classic. Indeed, it was to become a best-selling classic – vaulting its bold yet callow author into literary stardom, changing everything all at once.

The camel journey across the Outback as a 27-year-old was an uncommonly audacious act, for while the times were certainly a-changin’, sexism in mid-’70s Australia was still rife, and Davidson, though hardened by two years’ living in Alice learning about camels and saddles and the challenges of the desert, was socially green. If she regards herself at the age of 73 as unfinished – “I’m an old girl now,” she tells me – her younger self was by her own admission “feral” and barely formed.

Diggity number two follows us into the sandstone cottage, arranging himself with a drawn-out sigh beneath a dining table that has seen plenty of good times. It’s the centrepiece of a light-filled horseshoe-shaped kitchen and dining room enclosed by a veranda with ornamental eaves. A forest of picked flowers – both fresh and dried - springs from various vases and baskets. There’s a congenial chaos of pots and pans and cooking boards, tea and coffee makers, and plates displayed on a sideboard: a food lover’s kitchen. The author, dressed in pale jeans and a casual grey-and-olive cotton top, unfurls her hand towards two treats from the town baker: a quiche and a peach tart. “I’m a bit of Jew-ish mamma,” she says with a stage-Yiddish accent. “Eat! Eat!”

There’s a room in the house for a boarder and a lounge with a Yamaha piano flush to the street. Propped up on the music stand is the sheet music for works by Clara Schumann, wife of the composer Robert and muse of Brahms.

Tracks taught her very early about the importance of personality to literary success: she was the Camel Lady, the elvin tousle-haired blue-eyed blonde in the sarong. And she has dedicated her life since the October publication of Unfinished Woman to the all-important publicity push.

But the memoir took two decades to write, largely on account of its harrowing subject matter. It is coiled around the suicide of Davidson’s mother Gwen when the girl was just 11 years old. And it has taken a toll.

For the time being, Robyn Davidson is done with writing. “I honestly never want to write another word!” she declares in the slightly mannered English-accented tones of that troupe of expatriated Australian intellectuals who stamped their way over inner London in the late 1960s and ’70s.

Of course, this gesture in the direction of literary renunciation is largely a symptom of exhaustion – by the end of our conversation she is talking about some small writing projects that interest her. But it also hints at an ingredient in her complex self-image: she doesn’t see herself as a writer unless she is actually writing. “My identity doesn’t reside in writing the way it does for some writers,” she says. “Of course, it’s incredibly important for me. Literature saved my life in some ways. But unless I’ve got something pressing to say, I don’t really feel compelled to write.”

I raise the core thesis of The Wound and the Bow, by American critic Edmund Wilson, about the way the novels of writers as various as Dickens, Edith Wharton, James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway spring from a psychic wound or trauma; if ever there was a writer with a personal trauma at her back it’s Robyn Davidson. The new memoir lays it bare. Her telling of the story begins with a seemingly incidental detail: the gift of a pair of gold sandals from Gwen, which she wore one day, against her mother’s wishes, to school:

“Aren’t you even going to kiss me goodbye?” she said.

Not guilt nor love for fear must be allowed to weaken the momentum of victory. Without turning around, I flounced through the kitchen and out the front door. “No I won’t.”

When I came home that afternoon, my mother was dead.

The year is 1961. The place, outer suburban Brisbane. Robyn, her older sister and their parents had moved there a few years earlier from a cattle station west of Toowoomba. Her mother had been suffering, quietly, the whole time: loneliness metastasing into deep and inconsolable depression requiring electric shock therapy. In the memoir she circles around the words to say it, backs off, and, when she comes forward as clear-eyed as a seer, they are offered with a shockingly forensic brutality:

My mother hanged herself from the rafters of our garage, using the cord of our electric kettle.

The difference between her and Edmund Wilson’s cast of wounded artists, Davidson is adamant, is that her primal trauma didn’t turn into a “compulsion” to write. On the contrary, it was likely the psychic force that compelled her to escape – first to Sydney into the counter-culture by way of an abandoned Sydney cottage perfect for a solo squatter, then into work at a gambling joint, and finally into the desert. And yet she admits that before she’d written a word of Tracks she possessed, in some form, a “writer’s sensibility”.

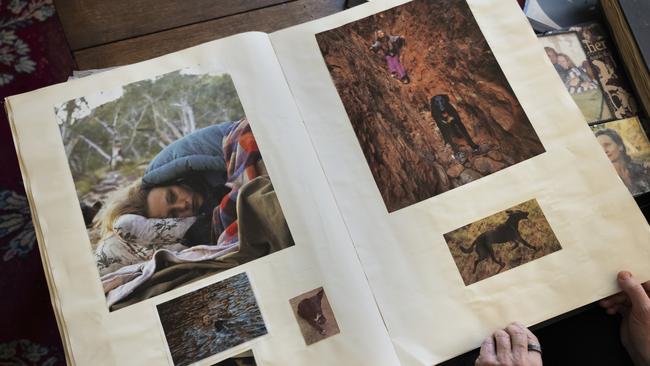

Close by in the kitchen there is a well-thumbed paperback by Spanish novelist Javier Marias, but her somewhat darkly lit library is larded with a mix of well-chosen paper and hard-to-get hardcover editions: the legacy of a lifetime in literature. “I give books away,” she says with a breezy gesture. “But the library somehow keeps growing.” On the shelves of a separate room stand various editions of all her books – including Travelling Light (a collection of her essays) and Desert Places: A Woman’s Odyssey With the Wanderers of the Indian Desert (a “book about failure” and the “angry twin” to Tracks) – as well as framed photographs of her younger self from the Tracks journey.

Does she recognise herself in these photos? “In some ways I don’t really,” she admits. “I don’t really recognise her. But that’s probably because there was so much fuss at the time about her and her identity.”

Reflecting on the way that journey – a journey undertaken as a “private act” – detonated around her, she writes in Unfinished Woman: “Fame, that grand deluder, puts you at risk of ceasing to be yourself. It distorts not just how you appear to others, which doesn’t matter much, but how you appear to yourself, which does. I knew this instinctively, and my response was to retreat from it.”

When Tracks was published in 1980 its instantacclaim and mega sales led to publicity tours and film offers (from Sydney Pollack no less) and a kind of rebirth. The “camel lady” had morphed into the “born writer”. With the proceeds Davidson bought a house with friends in an East End shoe factory. She was sought for her views of nomadism, feted by the London literary establishment. Literary fame would in time lead Salman Rushdie, winner of the 1981 Booker Prize for Midnight’s Children, to her door. In Unfinished Woman, Davidson writes in a veiled way about the passionate love affair that began in Sydney, finishing in London a couple of year later. She doesn’t mention him by name in print. The affair was, she now reveals to me bluntly, a “catastrophe”.

There is not, so far as I can tell, anything by Rushdie on the shelves. “I don’t read him anymore,” she says. “He’s sort of become... well, I don’t know, I shouldn’t say that… I think of him as a sort of Faustian figure. Salman had that terrible need to be famous, to be seen and acknowledged, and it has over-ridden those deeper things that produced Midnight’s Children. That brave and special book.”

The Davidson-Rushdie love story has been an open secret in literary circles for many years. I offer what turns out to be a partly mythical version and it draws her out if only to correct it. Then the story of this legendary literary affair unfurls.

In England Davidson had been a friend of the author of The Songlines, Bruce Chatwin, who died from AIDS in 1989 aged 48. They’d forged a connection, she says, “in part because we shared an interest in nomadism”. She pauses mournfully, looks at the table, and sighs “Dear Bru”, before continuing.

“Salman and I had shared a publisher so it’s sort of odd that we hadn’t met in London but we just… hadn’t. I’d returned to Australia and was living in Sydney. I’d left my then partner and was living on my own, very happily, in Annandale [in the inner west].

“Bruce and Salman had come over for the Adelaide Writers’ Festival and Bru had taken Salman to Alice Springs to meet friends of mine, who then became characters in The Songlines. They’re all there. Salman read Tracks while they were on the road and about 10 o’clock at night I get this phone call from Bru. ‘Darling! There’s someone here who absolutely has to talk to you.’

“I get on the line with Salman and it’s sort of instant. Both of us knew – it was the strangest thing. He was returning to England via Sydney. I said come for a meal. He came for a meal. And that was it – a coup de foudre [lighting strike]. But, I didn’t want it to go further than that.”

She gave herself heart and soul to a two-day love-fest, she says, because “I thought he would disappear, and I would be safe, it would have no future and I would have no responsibilities. A perfectly contained love affair. It was very intense. A falling into the being of another. But then two weeks later I got a letter to say, ‘I’m leaving my wife.’” She sighs once more, tucking her hands into the sleeves of her top, and her expression tightens.

“It was unstable from the beginning. Both of us were children really – f..ked up children. He was clever and funny – we made each other laugh a lot. And physically it was very intense and overwhelming on both sides, which is always sort of scary. Like always I leapt in without thinking of my own protection. I didn’t think I needed protecting. I’d been looking after myself since I was eight.”

She moved to London, bought a house with Rushdie, and for a time thought he was the one – “the partner of my life”. In time he proposed, and she explained that she wasn’t the marrying type, and things soured. She was present at the creation of what she describes as “that terrible book” – The Satanic Verses. He had planned to dedicate it to her, but it was re-dedicated after she left him. “I left him right before the book was about to be published but long before the Fatwah,” she recalls. “He knew quite well that it was going to create a huge furore; he was conscious of that.” She has never, she confesses, been able to read The Satanic Verses through.

When I ask her about the August 2022 stabbing of Rushdie at a public event in the US she says: “No writer should ever have to face persecution or attack. No person should. In so many places around the world, writers, artists, people who speak out, are being tortured and killed, or silenced one way or another. A Yemeni poet I met had been routinely tortured while in prison for years.”

It could be Rushdie’s eclipsing fame that led her not to refer to him by name in her memoir – whereas she identifies another love, the Indian aristocrat and politician Narendra Singh Bhati – indeed she begins to chafe as I pepper her with more questions about how it all unravelled. It’s clear the relationship with Rushdie was the one that cut closest to her core. “It really knocked me around,” she says. “And it wasn’t necessarily because of Salman per se. It was that the relationship cracked open the carapace.”

When she took up with Narendra she was, at first, unable to love fully, in part because she had loved too much. By losing herself she began, on the other hand, the journey toward herself – and towards her mother. “I hope I’ve given her some kind of voice,” she says of Unfinished Woman. “Some sort of presence. I’ve done my duty by her.”

Though a warm soul with a talent for love and friendship, Davidson is a tough judge of her younger self, a self that possessed both arrogance and ignorance “beyond measure”. And yet the Robyn Davidson who washed up in London was already a hard marker, quick to dismiss “anyone who doesn’t measure up to some kind of standard”. What was that standard? “I think it was simply a quest for the genuine without which all accomplishment was mere gloss,” she writes in Unfinished Woman. “Not greatness as measured by the outer world, but greatness within, a much rarer quality, and difficult to define.” She concludes these ruminations with an emphatic “yes, that was what she was looking for. That was what she had always been looking for”.

These days that toughness extends to her view of human nature. “I think humans are by default insane,” she tells me. “No joke. Our minds are completely out of control most of the time and capable of the most dangerous things. You just need to look at what’s happening in the world to know what those minds are capable of thinking and doing and believing,” she says, her eyes widening. “Taking the hate out of your consciousness is a very important thing for people to do. It’s a life’s work and everyone should be trying to do it.”

Would she describe herself as a gentle person? “I never want to hurt anyone,” she insists. “I’m strong but I don’t want to hurt. I’d probably rather allow myself to be hurt, and to shoulder the hurt, than to do the hurting.” She refuses to see this as a virtue, let alone a flaw. “It’s just a tendency. Increasingly I think that we should be neither proud nor ashamed of these qualities, these tendencies. They have so much to do with luck.”

For many years, particularly in her thirties, Davidson was desperate to shake herself free of the Camel Lady, her shadow. “People would come up to me and say, ‘That book changed my life,’ and I’d just go ‘Brrrrr’,’ she says, her shoulders raised into a shiver. “But now I think, ‘Well that’s not so bad.’ Young women still come up to say, ‘That book made a difference, because of your work I’ve done this or that’. Boys too, though fewer of them. And I think that if in some mysterious way I’ve been useful, and I might have done some good in this sorry world, then that’s something.”

There have been times when it looked as if the roots she’d put down elsewhere – in London, in the big house she’d bought with friends, or at a place in the Indian Himalaya with Narendra – would deepen and take hold. In the course of these years her reputation as a writer with a keen focus on nomadism grew and grew. She published a novel, Ancestors, a story about a young woman on a quest for her true self, and Desert Places. Her name became a byword for an adventure into which is enfolded a quest for selfhood.

What are her most cherished memories of a semi-nomadic life? “Travelling to Tibet. Staying in nomad tents in the high plains. Staying in a very remote Buddhist nunnery. Galloping a little nomad pony beside the Blue Lake of the Tibetan Plateau. Riding the pony to visit a Buddhist recluse in a cave – a rather well-appointed cave, it must be said.”

It’s the Victorian Goldfields region – hard dry skies not so unlike those of her first love, the Central Desert – that has claimed her. She has lived here, now, for close to a decade, in a house that she writes of movingly in an epilogue to the memoir: the house where we sit, over treats, and talk of what is past, or passing, or to come.

“The house has provided refuge for a number of years, a sanctuary in which to sort through the scraps, complete the book,” she writes in Unfinished Woman. “I suppose the house will see me out, but who knows? In any case, when I die, it will transform again, and all it contains will tumble through time into new configurations, with entirely different meanings. We are not the owners of anything…”

She takes me for a tour of the garden, gesturing to a spot up against the rear fence where she might or might not build a small flat, and the remains of a deep concrete fishpond that she may or may not turn into a plunge pool. The place ticks her two key boxes: room for a garden and proximity to a café. And there’s a good bakery, and a decent pub – and a theatre nearby. “And I can see kangaroos – I’ve had them up the back yard.”

Does she, after years spent hopscotching between England, Australia and the Indian subcontinent, finally feel settled? “Well I don’t think I ever do feel entirely settled,” she answers with a small shrug of resignation. “I think it’s a temperamental thing. It could be genetic. They say there are some wolves – one or two in each pack – who don’t fit in easily. And they tend to wander off, go into new territory, and others follow.” b

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout