The real Queen Camilla and the love story behind the throne

She was the woman least likely to be Queen. Spat on in the supermarket, banished by the tabloids, loathed by the public. So how did Camilla turn it all around?

Nothing about Camilla Shand’s beginnings seemed destined to end on a throne. Girls like Camilla were expected to marry well, breed enthusiastically and spend their days running ramshackle houses – and, for most of her life, she did just that. “She didn’t stand out in any way,” a teacher once said. “There was nothing special about her.” But this apparently unremarkable upper-middle-class girl had a youthful dalliance, which became an extramarital romance and ultimately, in middle age, the enduring love story of two lives, with Charles Philip Arthur George, Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and heir to the throne of Great Britain. Sometimes, she once observed, you have to stick your head above the parapet. Ironically, she never wanted to. Somehow, she ended up queen.

It was touch and go. Camilla was pushing 60 when she and Charles finally married in 2005, 35 years and two failed marriages after they met. Even Queen Elizabeth, who for many years would have nothing to do with her son’s mistress, was touched almost to the point of sentimentality, commenting in her speech at the reception: “My son is home and dry with the woman he loves.” She then made a swift exit to watch the Grand National.

On the day, Camilla was so nervous and ill that her sister had to threaten to wear the wedding dress herself if she wouldn’t get out of bed. Her bouquet, when she made it to Windsor register office, included flowers symbolising return to happiness, you complete me, and married love. Posing for photographs with the happy couple, her new stepsons, William and Harry, did a passable impression of not hating the woman they blamed for ruining their mother’s life. They were, they claimed, “100 per cent” behind the newlyweds, a lie that persisted until Harry rubbished it years later in his memoir Spare. On April 9, Charles and Camilla will celebrate their 20th wedding anniversary, for which the traditional gift is china. A coronation mug might be nice.

Camilla grew up in Sussex, the eldest of three children of Major Bruce Shand and Rosalind Cubitt. Her father was independently wealthy, a decorated army veteran turned wine merchant. Her mother’s ancestor Thomas Cubitt built the balcony of Buckingham Palace and developed the exclusive London enclave of Belgravia. Her great-grandmother, Alice Keppel, was the mistress of Edward VII and, according to Shand family legend, was known to say, “My job is to curtsy first, then jump into bed.” Evidently, it ran in the family.

With her younger sister Annabel and brother Mark, Camilla spent her early childhood at the Laines, a sprawling house with a croquet lawn opposite a racecourse in East Sussex. Her parents, unusually for their class and the time, raised their children themselves, without a nanny, and showered them with love. According to family friends, the Shand children were, as a result, friendly, confident and likeable.

“They’ve always been quite chatty,” their father once observed. “There haven’t been any inhibitions in their upbringing that I know of.”

Three miles up the road was her first school, Dumbrell’s, a rigidly disciplined co-ed establishment where the day began at 7.30am with 29 minutes of “violent exercises”. In her biography of Camilla, Rebecca Tyrrel writes that any child who left belongings lying around was required to wear them. As a result, one little girl ate lunch wearing three hats, while another had a large sewing basket tied to her waist. Afternoon activities might include learning to prepare soft fruit while a teacher read from the classics. A contemporary of Camilla’s remarked that a child who could cope with Dumbrell’s could cope with anything. Needless to say, Camilla coped. She has described her childhood as “perfect in every way” – climbing trees, eating jelly and ice cream at the “duckling dances” organised by her parents for local boys and girls, and riding her pony. “We were brought up not to be centre stage,” her sister Annabel told Robert Hardman for his book Charles III.

Aged ten she arrived at Queen’s Gate school, near the family’s London townhouse in South Kensington, with much the same hairstyle that she has today. As a teenager she was apt to sneak onto the roof for a cigarette, and she left at 16 left with one O-level and a reputation for being excellent at fencing. At Mon Fertile, a Swiss finishing school, she learnt how to organise a table placement, ski proficiently and run a big house. Suitably finished, she proceeded to Paris to study French and French literature before returning to London to be launched on the capital’s social scene where it was expected she would make friends, have a jolly time and fulfil her destiny in the home counties. “She is,” a friend once commented, “a frightfully nice person. She had frightfully nice parents. She is a very jolly girl. She is simply someone about whom there is nothing bad to say.”

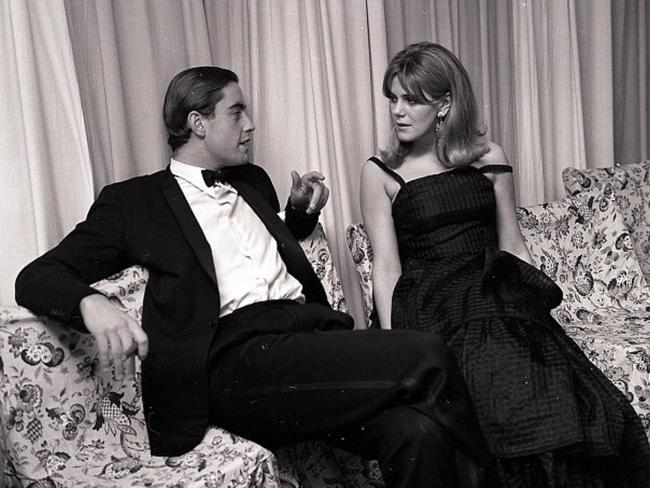

In 1965, her parents threw her a “coming out” party for 150 at Searcys, a fashionable venue just behind Harrods in Knightsbridge. A photograph of her appeared in society magazine Harpers & Queen, wearing a form-fitting black dress that showed off her cleavage, and chandelier earrings. “Camilla was never going to be Deb of the Year,” remarked one of her contemporaries, “but she was determined to have the best fun she could.”

“Fun” is a word that has followed her around her whole life. “If you wanted a party to go with a swing,” one contemporary noted, “you invited Camilla.” According to novelist Jilly Cooper, an old friend from Gloucestershire, “She’s a terrific laugh ... I don’t know anybody who cheers one up more than she does. Her ability to see the funny side of life has made an enormous difference over the years.”

Her first boyfriend was a 19-year-old Etonian named Kevin Burke, whom she dated for a year. Burke drove a yellow Jaguar, which she nicknamed “Egg”, and he later described their year of nightly cocktail parties and dances as “the best time, and I had the best partner you could wish for. She was never bad-tempered. She knew how to have fun”.

By now, Camilla was sharing a flat in London with a girlfriend, Virginia Carrington. Her bedroom was described by one visitor as “typical Camilla. It looked like a bomb had hit it”. Carrington affectionately described how her flatmate had a complete “inability to hang anything up and an aversion to cleaning fluids of any description. You should see the state of the bathroom when she’s been in it.” Camilla briefly moved on from Burke with another Old Etonian, banker Rupert Hambro. But then, when she was 19, she met a dashing army officer, Andrew Parker Bowles, and was smitten. According to legend, the first time she set eyes on him at a party she said, “Introduce me to him now.” They dated on and off for seven years, but Parker Bowles was not a man to let this cramp his style; he continued to cut a swathe through high society while spending “many, many nights” with Camilla. According to Tyrrel, he “schooled her in the ways of the world” and taught her that sexuality was healthy. One weekend visitor to his Notting Hill flat found a dishevelled Camilla sitting on Parker Bowles’s knee wearing one of his shirts. On another occasion, Camilla berated him on his own doorstep while he was in his underpants after she caught him with another woman.

Another of Parker Bowles’s early conquests was Princess Anne, leading some to suspect an element of one-upmanship in what happened next. “It seems likely,” writes Tina Brown in The Palace Papers, “that her dalliance with Charles was a ploy to make Andrew jealous.”

“She was determined to show him [Andrew] that she could do as well in the royal pulling stakes as he had done,” one of the polo crowd told Robert Lacey. (Princess Anne later said of Camilla, possibly with a wry smile, “I’ve known her a long time, off and on…”)

“Andrew behaved abominably to Camilla, but she was desperate to marry him,” said one of his girlfriends, Lady Caroline Percy, who once dismissed a jealous Camilla with the words, “You can have him back when I’ve finished with him.”

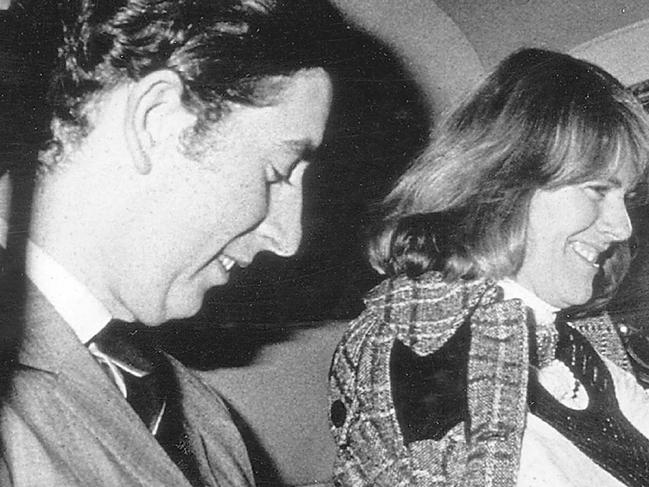

Charles and Camilla first met when she was 24 and he was 22. They were introduced at a dinner party by a friend of his, Lucia Santa Cruz, who lived in the same block of flats as Camilla and Carrington. They enjoyed nights out together dancing at Annabel’s nightclub and at the opera in Covent Garden, and spent weekends at Broadlands, the Mountbatten family home, where, according to Tina Brown, Camilla helped him to overcome his shyness in bed by telling him, “Pretend I’m a rocking horse”. They shared a fondness for The Goon Show – their nicknames for each other, Fred and Gladys, are from that series – and Camilla was adept at cheering up the slightly forlorn, self-pitying Prince of Wales, who was already moaning that his life was “intolerable”.

“Your spirits rise whenever Camilla comes into a room,” Lord Beresford told Robert Lacey for his book Battle of Brothers. “You can tell from her eyes and the smile on her face that you are going to have a bloody good laugh.”

According to Brown, “The prince adored her carelessness and utter absence of sycophancy,” and, in a foreshadowing of Prince William’s affection for the Middletons, he was “charmed” by Camilla’s family, “whose relaxed warmth was the polar opposite of his own”. He was also well aware of his uncle Lord Mountbatten’s maxims: that while he, as a man, should “sow his wild oats” before marrying, his bride must very much not. Or as Mountbatten put it, “A bedded can’t be wedded.”

In other words, it was clear to everyone, possibly including Camilla, that she was an acceptable girlfriend but not an acceptable bride. In December 1972, they spent a final weekend together at Broadlands before Charles, then 24, departed in the new year on an eight-month deployment with the Royal Navy to the Caribbean. According to broadcaster Gyles Brandreth, a friend of Camilla’s, “Charles declared his love but not his hand. He whispered sweet nothings, but said nothing of substance. He made no commitment and he asked for none.”

If the affair was at least in part a ruse to gain Andrew Parker Bowles’s attention once and for all, it worked. Parker Bowles put a ring on it while Charles was away, bounced into proposing after seven years when his father and Camilla’s conspired to place an engagement announcement in The Times. “I suppose,” Charles wrote in a letter, “the feeling of emptiness will pass eventually.”

They married when Camilla was 25, in front of 800 guests in the Guards’ Chapel at Wellington Barracks, near Buckingham Palace, which was so packed it was standing room only. The principal witness signing the registry was Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother.

Parker Bowles was no more faithful after he married than before, but no one knows for sure when Charles and Camilla resumed their relationship. Charles infamously told his biographer, Jonathan Dimbleby, that it was only once his marriage to Diana had “irretrievably broken down”. Others, however, describe Camilla having assignations with Charles at her grandmother’s house not long after she had her first child. Lord Charteris, the Queen’s private secretary between 1972 and 1977, told the Queen that her eldest son was sleeping with the wife of an officer in the Guards “and the regiment doesn’t like it”. From then on, “We were warned never to include Mrs Parker Bowles in the guest list for any formal event where the Queen was to be present,” said a former member of the household.

Yet Camilla and her husband were happy. Visiting them at home in 1981, Tina Brown found their relationship to be “a kind of ‘electric indifference’” and it was generally agreed that they had a very “English” marriage: he would entertain himself in London during the week while Camilla would keep the home fires burning in Wiltshire, bring up the children and have a roast on the table on Sundays.

According to one story from the time, she was waiting for Charles at her grandmother’s house one day, wearing jeans with a broken zip held up with a safety pin. Her grandmother protested that she must change before he arrived, saying, “I can even see your drawers, Camilla.” Camilla replied, “Oh, Charles won’t mind about that.” Shortly after he arrived, they disappeared upstairs. Tina Brown argues that she was “sexual and emotional comfort food for Charles”, a man who needs to be “soothed and amused by a woman who can be both maternal and subtle in her controlling hand”.

Constitutionally, however, rather more was required of Charles than being soothed and amused by a married woman. He needed a bride and an heir, and Camilla was neither maternal nor subtle when it came to vetting his options. Whether it was for their suitability as royal brides or possible threats to her own status, or both, no one knows. Certainly, Princess Diana told journalist Andrew Morton that Camilla made no secret of her intimate knowledge of Charles’s diary and whereabouts, and asked her twice over lunch when she was engaged if she planned to hunt when she was married. (Diana did not. Hunting with the Beaufort was one of Charles and Camilla’s regular pastimes, with one friend describing Camilla approvingly as the sort of woman who went straight from hunting to a black-tie party without bothering to shower.)

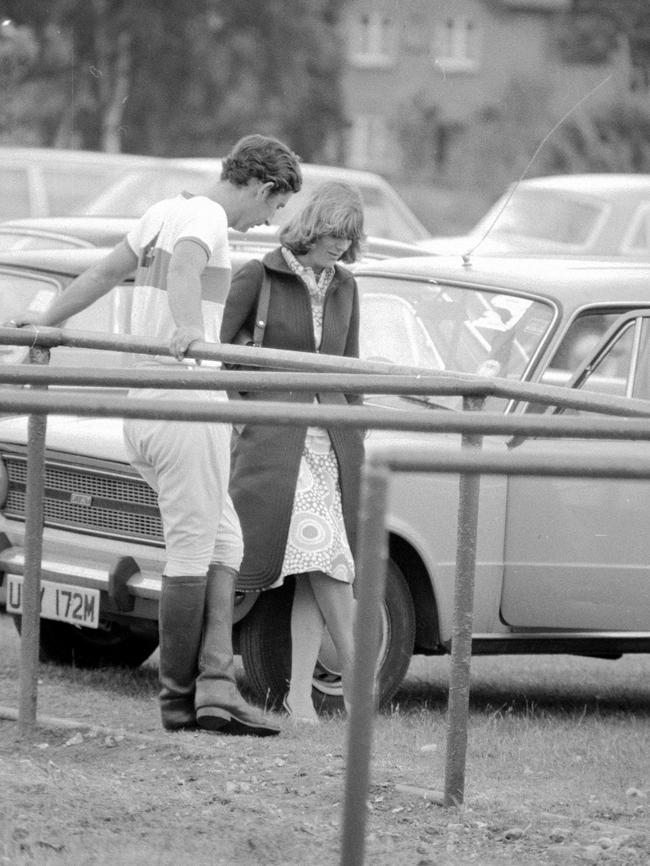

Another of Charles’s pre-marriage girlfriends, Anna Wallace, did hunt and was duly routed. Camilla spent the summer of 1980 openly canoodling with Charles at various social events until Wallace got the message after one public humiliation too far at the Queen Mother’s 80th birthday party. “I’ve never been treated so badly in my whole life,” she told Charles before leaving early. “Nobody treats me like that, not even you.”

Camilla was not the only one to conclude that Lady Diana Spencer was rather more tractable; according to Tyrrel, she described her as “a mouse”. When Tina Brown wrote a cover story questioning the state of Charles and Diana’s relationship in 1985, four years after they married, it was headlined “The Mouse That Roared”. It described Diana as “the shy introvert unable to cope with public life [who] has emerged as the star of the world’s stage”. Charles, on the other hand, had withdrawn into an “inner world” and was “pussy-whipped from here to eternity”. Both, Brown wrote, were alienated by the change in the other.

Through it all, or most of it, or now and then, depending on who you believe and when they were talking, was Mrs Parker Bowles – conveniently up the road from Highgrove, the country house in Gloucestershire that Charles had bought for himself before his marriage.

“Camilla never passed judgment,” a friend once said as Charles and Diana’s marriage went south. “She was never particularly nasty about Diana. She was just a great, great friend who would listen for hours and never get bored.”

Whenever the affair resumed – Diana was convinced it never ended – they had plenty of discreet friends with big houses at the end of long drives willing to accommodate them: the Mountbattens at Broadlands; the Palmer-Tomkinsons in Hampshire; the Duke and Duchess of Westminster on their vast estate in Cheshire. One of Camilla’s oldest friends is Fiona Shelburne, Marchioness of Lansdowne and chatelaine of Bowood, a magnificent Georgian pile in Wiltshire. Her loyalty was rewarded with the position of Queen’s companion and a key supporting role at the coronation.

Behind the scenes, the affair, and its effect on Charles’s marriage, was causing consternation. Michael Shea, Queen Elizabeth’s press secretary with responsibility for managing Charles and Diana’s media coverage, told Tina Brown that after the birth of Prince Harry in 1984, Princess Anne and her brothers were thinking about writing to Charles to protest about his behaviour with Camilla. He added that the Queen and Prince Philip “felt the same”, but he didn’t know if they’d ever gone through with the idea. The affair continued. One friend of Charles mused that the attraction lay in the fact that “practically everything he says to her is going to be interesting. If he is telling you about something that happened with his mother, the Queen, then it is automatically fascinating. Camilla has a ringside seat. I think that’s what she likes, the ringside seat. She knows the truth.”

Another suggested that at some point in her marriage, Camilla simply realised that her husband didn’t need her but her lover did. Princes William and Harry, were, according to writer Tom Bower, collateral damage when their parents separated. Both boys blamed Camilla squarely for their parents’ break-up, with Harry recalling in Spare being summoned from Eton to meet her for the first time over tea. “I told myself no big deal. Just like getting an injection. Close your eyes, over before you know it. I have a dim recollection of Camilla being just as calm (or bored) as me. Neither of us much fretted about the other’s opinion. She wasn’t my mother and I wasn’t her biggest hurdle. In other words, I wasn’t the heir.”

Camilla played a “pivotal role in the unravelling of our parents’ marriage”, he continued, “but we understand that she’d been trapped like everyone else in the riptide of events. We didn’t blame her. In fact, we’d gladly forgive her if she could make Pa happy.” (He slightly spoilt the magnanimous effect while promoting his book on TV by claiming that she was happy to leave bodies in the street in pursuit of good press coverage for herself. “I don’t look at her as an evil stepmother,” he said. “I see someone who married into this institution and did everything she could to improve her own reputation and her own image, for her own sake.” Harry perhaps didn’t realise, or left unsaid, the parallels with his own wife.)

Even though Charles and Camilla’s relationship was an open secret among their friends as the ’80s turned into the ’90s, it remained largely below the radar. Her marriage rolled on, while his marriage quietly imploded and everyone looked the other way. What finally blew up the status quo was the publication in June 1992 of Andrew Morton’s book, Diana: Her True Story, which detailed Diana’s belief that Camilla was to blame for the failure of her marriage. That December, British Prime Minister John Major announced to a packed House of Commons that the Prince and Princess of Wales were to separate.

The fallout for Camilla from the book and the breakdown of Charles’s marriage was immediate and prolonged: hate mail, abuse in the street, and being hounded by photographers who camped outside her house. It was said to be ten years before she dared set foot in a London restaurant. “Obviously if something has gone wrong I’m very sorry for them, but I know nothing more than the average person in the street,” Camilla told reporters with a straight face as she retreated with her sister to Bowood. “I only know what I have seen on television.”

Andrew Parker Bowles gamely described reports about his wife and the Prince of Wales as fiction. Her mother declined to comment with the words, “None of us has ever broken ranks.” But worse was to come. In January 1993 the “Camillagate tapes” were published. Recorded by an amateur radio enthusiast four years previously, they included an intimate phone conversation between Charles and Camilla in which he expressed his desire to be reincarnated as her tampon; the tapes made an international laughing stock of the heir to the throne and his mistress.

Opinion polls were merciless. Seven out of ten people said that the tapes had done “great damage to the monarchy”. The public, it was said, wanted the throne to skip straight from Queen Elizabeth to Prince William. Even Charles’s father, the Duke of Edinburgh, said that he was simply “not king material”. The diarist James Lees-Milne spent a weekend at Chatsworth with Camilla and her husband in September of that year. He wrote that Camilla “has lost her sparkle. Women spit at her in supermarkets… She walks with bowed head and has trained her fluffy hair to cover her cheeks.”

A housekeeper at her former brother-in-law’s house in Wales was less sympathetic. She claimed Charles and Camilla had been regular and frequent guests since 1992 and described her as “quite snooty, you know. Quite grand and she doesn’t tip. And I’m not terribly keen on her habits. After she’s been staying, I find knickers all over the place.”

Yet it appeared that she had no wish to be divorced. She and Parker Bowles had an amicable arrangement. “They will never divorce,” Simon Parker Bowles said of his brother and sister-in-law. “While the relationship is rather eccentric, it appears to work.”

And then, suddenly, it didn’t. The façade crumbled in 1994, when Charles admitted adultery. In spite of Camilla’s misgivings, he co-operated with a biography by Jonathan Dimbleby and agreed to a TV interview, in which he confessed that he had remained faithful to Diana only until his marriage had “irretrievably broken down”. Andrew Parker Bowles felt publicly humiliated and filed for divorce. Camilla’s friends felt that she’d been thrown to the wolves after years of devoted discretion, and at a time when her mother was seriously ill. (She died in July that year aged 72.)

Tina Brown argues that at this point, and for the next few years, Camilla’s situation was parlous in the extreme. Her ex soon remarried. Her children were away at university. She was not exactly flush with cash, and there were rumours that Charles had stumped up some of the money to buy her post-marital home, Ray Mill House in Wiltshire. It remains her private residence and, she has said, “the one place I can be completely relaxed on my own terms”.

Charles helped out: he sent over horseboxes full of flowers and trees from Highgrove for her to plant in the garden. Her supermarket shop was charged to his account. If she threw a dinner party, his chef was dispatched to cater it, and her horse was stabled at Highgrove.

But Camilla had no official role in the prince’s life and could theoretically be dropped at any point. She could do what she liked and had none of the tedium of royal life to put up with, but she was also persona non grata for the royal family and the general public. Unless and until he made it official, she was vulnerable to palace intrigue, public opinion and the luminous, eternally wronged presence of Diana. On the other hand, as a friend told Tina Brown, “Camilla is a smart poker player.”

In 1996, she was instrumental in hiring a spin doctor named Mark Bolland to rehabilitate her public image – from the villain who ruined Diana’s life to the loving partner who made Charles’s bearable. Camilla installed her old friend Virginia Carrington on Charles’s staff to run his personal schedule. She and Charles were photographed for the first time as a couple, coming out of the Ritz. Charles threw her a 50th birthday party at Highgrove, where she was wore a new necklace he had given her. (She told the chauffeur to slow down as they arrived at the gates so photographers could get a good shot. To this day, she is admired by press photographers for her willingness – unusual in the royal family – to help them get the shot they need.) Slowly, Bolland’s plan for public acceptance of Camilla appeared to be working. Diana was out of the country on holiday, apparently happy. It was July 1997.

For a year after Diana’s death, Camilla effectively went to ground once again. In private her relationship with Charles continued and in public the brickbats kept coming. American fashion critic Richard Blackwell, famed for his “worst dressed lists”, described her as “the queen of frump – the biggest bomb to hit Britain since the Blitz”.

By 1998, though, Bolland was on manoeuvres once again. It was reported that Camilla had met Prince William and the sky had not caved in. She was photographed arriving at Highgrove with her sister for Charles’s 50th. She went to the opening of a London jewellery boutique with her daughter and smiled gamely for the cameras. She played a long game and kept her counsel, a devotee of Queen Elizabeth’s maxim, “Never complain, never explain.”

But even by 2002 her situation was open to question, with Queen Elizabeth inclined to agree with some of her advisers that Camilla was surplus to requirements. Sir Michael Peat, a senior courtier, was dispatched from Buckingham Palace to Clarence House, the heir to the throne’s HQ; his orders were to sort out Charles’s “chaotic” household and “sever” his relationship with Camilla, which was deemed a messy distraction for Charles and a potential lightning rod for adverse public opinion. Peat, however, concluded the opposite: Camilla was good for Charles and he should “marry her and be done”, as Tina Brown puts it.

It was now five years since Diana had died and nine since the Parker Bowles divorce. Characteristically, though, Charles dithered, reluctant to be pushed into a corner and unable to propose even when a former Archbishop of Canterbury said it would be “the natural thing” for them to marry. Before he died, Camilla’s elderly father even petitioned him to make an honest woman of his daughter.

It was the marriage of another couple that was the final straw for Camilla, jolting Charles into action. In November 2004, the daughter of the Duke of Westminster was marrying Charles’s godson, Edward van Cutsem, at Chester Cathedral. Days before the wedding, Camilla, who had been living with Charles at Clarence House since the year before, discovered that she would not, as expected, be seated directly behind Charles in the church. Instead she was effectively in Siberia, at the back, behind a pillar, with the bride’s family. She took it as an insult and said she wasn’t going. If Charles went he would go alone, which would itself invite speculation. In the end, he fudged and announced that a sudden urgent appointment on the day prevented him from attending.

Charles proposed over new year, with a 5ctdiamond ring from the collection of his beloved grandmother. Time magazine put them on its February cover with the headline “Charles and Camilla. Love Actually”. Prince Harry said recently in a TV interview that he and William “didn’t think it was necessary” for their father to remarry, and begged him not to. “We thought,” he said, “it would do more harm than good.” The marriage went ahead anyway.

Slowly, in classic royal fashion, Camilla was incorporated into “The Firm”. By the time the Queen died in 2022, the long-running dispute about the Duchess of Cornwall’s future title had been settled. On the eve of her Platinum Jubilee, in February 2022, Queen Elizabeth announced her “sincere wish” that when the time came Camilla should be known as Queen, and that was that.

In May 2023 she was duly crowned Queen alongside her husband.She wore a gown embroidered with the names of her children and grandchildren and her two rescued Jack Russell terriers, Bluebell and Beth. That day, the Court Circular quietly started to refer to her simply as “the Queen”.

In the first year of the new reign, Charles and Camilla racked up 571 engagements between them and, when he was diagnosed with cancer, she refused to cancel any of her own undertakings. She still retreats to Ray Mill when she can, where the garden is full of grandchildren and people telling her, “You’re not Queen to us – totally irreverent,” her sister says. “People can see that she’s not someone up ‘there’ to be revered. She’s an ordinary person who has gone through the same things we all have.”

One very old friend of Camilla’s watched the coronation almost in disbelief. “When I think back to those days when she was getting so much grief, and how she soldiered on without complaining out of loyalty and love, then you look at today? Well, I was in floods. This felt like proper closure.”

“Basically,” her sister says, “she makes him laugh. And he brings to her, well, everything.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout