The man on a mission to save our coral reefs – by growing them in London

If there is any hope of saving the world’s beleaguered coral reefs, it will emanate from the pioneering work being carried out here, in the unlikely confines of Jamie Craggs’ basement aquarium.

“It’s going! It’s going!” someone shouts. We hurry up a short flight of steps to an illuminated aquarium tank hidden behind a blackout curtain. There we witness the start of what my host, Dr Jamie Craggs, calls “the magic”, and it is a strikingly beautiful sight.

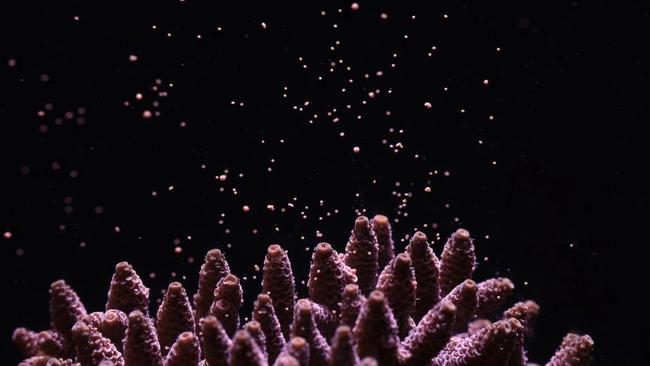

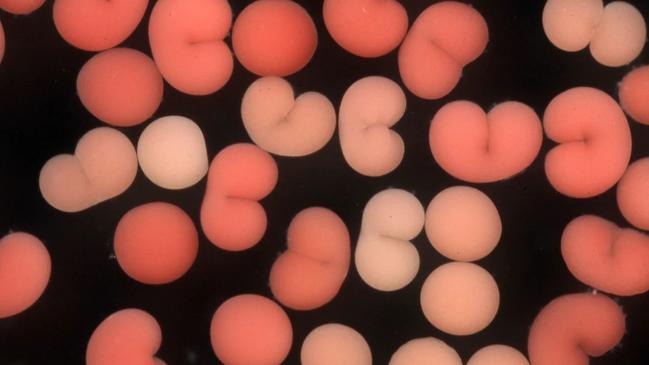

On the floor of the tank a small coral, around 15cm high, is beginning to spawn. Its thousands of “polyps” – small, sac-like organisms embedded within its hard walls – are releasing what Craggs aptly describes as an “explosion” of tiny, pinkish, luminous balls, little bigger than pinheads. Masses of them float slowly and serenely to the surface against a deep blue background.

It is a rare privilege to see a coral spawn: the process happens just once a year, and generally lasts less than 30 minutes. I watch, mesmerised, but Craggs has work to do.

Each ball, or “bundle”, contains as many as a dozen eggs, and thousands of spermatozoa. He begins swiftly collecting the bundles with a pipette tube, then rushes them down the steps to a tiny laboratory. There, two biologists will attempt – for the first time in Europe – to cryogenically freeze the sperm so the corals can potentially be reproduced a hundred or a thousand years hence, should today’s coral reefs be destroyed – as seems likely – by climate change.

Meanwhile, Craggs and his assistants will attempt to fertilise the eggs with the sperm of other coral species, in order to develop hybrids better able to withstand the steadily warming oceans. In short, it comes down to this: if there is any hope of saving the world’s beleaguered coral reefs, it emanates in part from the pioneering work being carried out here, in the unlikely confines of a basement aquarium in the Horniman Museum in deepest south London.

Founded by a Victorian tea trader 124 years ago, the little museum in Forest Hill is a 50-minute ride from Trafalgar Square on the 176 bus – and about as far from a coral reef and turquoise sea as it is possible to be.

Craggs, 48, is the aquarium’s principal curator. Growing up in Brightlingsea on the Essex coast, he spent much of his time in, on or beside the North Sea – crabbing, rock-pooling, swimming, sailing and windsurfing. He acquired his first fish tank at the age of 10, and soon graduated from keeping goldfish to tropical freshwater fish and then marine animals. After studying ecology and marine biology at university he spent three months researching coral reefs in the Philippines and another 18 as a cameraman filming reefs off Borneo. From the London Aquarium, where he was the head aquarist, he moved to the Horniman in 2008, and has since devoted his professional life to a quest to save the world’s endangered corals.

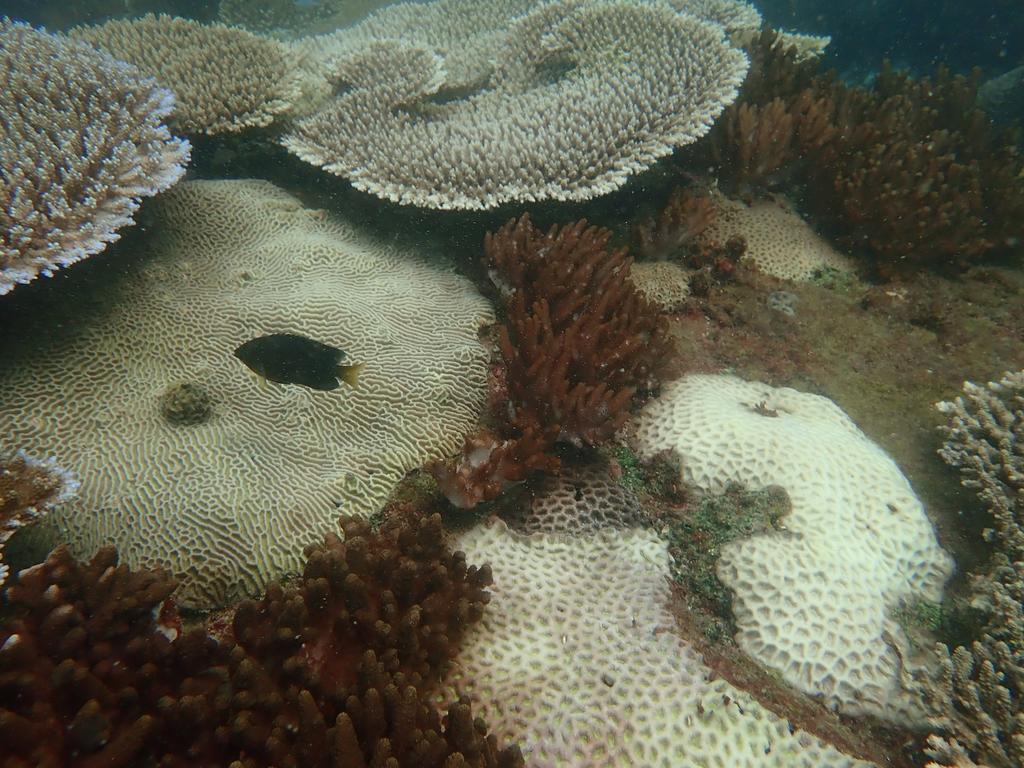

“Corals are such important animals in our ecosystem,” he says. “They’re incredibly diverse habitats. One square metre of coral reef contains as many different types of animals as a whole hectare of Amazon rainforest.” But, he adds, “as a result of climate change we’re losing those corals. They’re in desperate need of help.” Half are already in trouble, including the Great Barrier Reef; studies show as many as 90 per cent will be afflicted if the planet heats up by another 1.5C – the best-case scenario foreseen by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Research has found that an increase of two degrees would mean practically none surviving in anything like their present form.

In 2012 Craggs launched Project Coral in what is essentially a long, largely windowless corridor on three levels that is hidden away behind the aquarium that the Horniman’s visiting public sees. Its walls are lined with corals, mostly hidden behind blackout curtains, and a tangle of pipes and electric cables. It is so narrow that he and his three assistants have to perform what they call the “Horniman shuffle” to get past each other. “It’s not a cutting edge facility, that’s for sure,” Craggs laughs.

He nonetheless enjoyed a swift and seismic breakthrough. That first November he spotted a tweet from a Fijian diving company offering customers the chance to watch corals spawning at sea two days later. From that exact date he managed to work out the lunar cycles, day lengths and water temperatures in the months leading up to the spawning, then crudely replicated them in the Horniman’s aquarium. The following year he and his team became the first researchers in the world to induce a captive coral to spawn not by accident, but purposefully and at a time of their own choosing.

It happened at 11.30pm one September night. “It was amazing, absolutely phenomenal,” Craggs remembers. “There was a lot of whooping and cheering, and at that moment I realised its exact potential.”

He gradually refined the technique. He put probes on coral reefs, studied NASA charts and amassed data on sunrises, sunsets, lunar cycles and nutritional inputs from different parts of the world. He fed that information into computers and produced a program for each of the aquarium’s 50-odd species of coral, garnered from around the world, that would exactly replicate their natural environments.

Above each tank adjustable LED lights now simulate the rising, setting and arc of the sun each day. Half ping-pong balls stuck over other lights do the same for the moon. The water is ordinary London tap-water, but with the impurities filtered out and salts added to replicate seawater. “We don’t have the luxury of the beautiful tropical ocean right on our doorstep so we start from base tap-water,” says Craggs.

By manipulating those conditions, by pushing lunar and solar cycles forward or back, Craggs and his team have since managed to manoeuvre all the aquarium’s corals on to the same time. The corals all now spawn within a week of each other, and at a precise time of the team’s own choosing.

In addition to that, Craggs has tricked the corals into spawning at the start of the working day by making them think it’s sunset, which makes life far easier for researchers. He points to a red digital clock on a wall. It shows what he calls “coral time”. “To them it’s 6.53 at night. For us it’s 10.53 in the morning,” he says.

His team’s next goal was to induce the corals to spawn not once but twice a year, in order to double the scope for research. lt has succeeded with some corals, but this remains a work in progress. “The problem is that corals are like pandas,” says Craggs. “We have a one-hour window to collect the eggs and sperm and do the research. We then have to wait a whole year to get access to those eggs and sperm again.”

This “phase-shifting” was a truly groundbreaking new technique, and one that the Horniman has since shared with at least 20 other aquariums and institutions around the world, from Australia, the Pacific Islands and the Maldives to the Middle East and Caribbean. The museum has also made it available to any interested party on the internet.

“We’ve pioneered a technique in this tiny little facility which is now globally recognised,” says Craggs. “It gets used around the world so I’m very proud of that.”

What this planned and predictable spawning in aquariums does is allow scientists and researchers to acquire, study and experiment with coral eggs and sperm in a way they seldom, if ever, could before. And different institutions are using that priceless “tool” in different ways.

Some – like the Florida Aquarium in Tampa – are using it to restore and rebuild reefs damaged not just by climate change but by fishing, pollution and other human activities. They select the hardiest individual corals from a single species, sometimes from different geographical zones, and induce them to spawn. They then fertilise them through a coralline version of IVF, and let the ensuing polyps grow to a certain size and strength in artificial conditions before replanting them on struggling reefs. “This helps future-proof that restoration strategy because you’re helping bring new genetic diversity to the population you’re planting out,” says Craggs.

Keri O’Neil, the Florida Aquarium’s director and senior scientist, says: “Craggs’ groundbreaking work in coral reproductive biology has truly revolutionised how we approach conservation and research. His innovative techniques for predictably inducing coral spawning in human care have paved the way for unprecedented advances in coral restoration.”

Michael Webster, an environmental studies professor at New York University, adds that successfully breeding corals in captivity is a “critical first step” towards producing corals capable of surviving stressful conditions.

But the Horniman and some other institutions are going a step further. They are experimenting to see whether they can cross different species to produce a hybrid coral better able to withstand the warming seas. Craggs has recently discovered, for example, that he can cross-fertilise one species of coral from Australia with another from Fiji.

He is at pains to stress that these genetically modified hybrid corals will not be planted in the oceans lest they supplant existing species. The work is a “safeguard to find out what’s possible,” he explains. “We’re increasing the available toolbox for use in the worst-case scenario.”

Yet neither developing hardier versions of existing species, nor creating more resilient hybrids, is likely to save the world’s corals if humanity fails to tackle climate change, so Craggs and his team are also working on a doomsday solution with shades of Jurassic Park: the cryo-preservation, or deep-freezing, of coral sperm to give future generations the chance to recreate coral long after it has gone extinct.

There are two other scientists working at the Horniman on the day 1 visit. They are Tullis Matson, the ebullient founder and chairman of a company called Nature’s Safe, and Debbie Rolmanis, his chief operating officer.

To date their company has frozen the sperm or tissue of 256 species of animal ranging from the southern white rhinoceros and Asian elephant to the extremely rare and endangered mountain chicken frog, which is found only on the Caribbean islands of Montserrat and Dominica. That material is stored at minus 196C in a top security “biobank” in rural Shropshire. Matson likens it to a “nuclear bunker” with its concrete roof, steel doors and CCTV cameras.

On this particular day Craggs rushes the “bundles” from the spawning coral – a species called Acropora kenti – down to the tiny lab where the two biologists are waiting. There, he gently shakes the tube containing the “bundles” until they burst, releasing their eggs and sperm. Matson and Rolmanis then siphon off the sperm and swiftly freeze it in liquid nitrogen.

Scientists in the US have managed to cryo-preserve coral sperm before, but this is the first attempt to do so in Europe. “It’s unbelievably exciting,” Matson says.

Two days later Craggs calls him with good news. Of the Acropora kenti sperm only eight per cent were still able to fertilise eggs after being frozen and unfrozen, but of the sperm of another species, Acropora millepora, 45 per cent could do so.

Matson is thrilled. “This is groundbreaking,” he says. “It’s incredible, it really is... We have dealt with sperm cryopreservation for 30 years, but this has to be one of the highlights. It’s not just that we’ve managed to freeze coral sperm and thaw it out and get embryos. It’s the implications of this for the future of coral. We’re just at the start of something extra-special in cryopreservation of coral.”

The next challenge is to freeze coral eggs, so the frozen sperm will have something to fertilise, and for that Matson must wait for next year’s spawning season – unless Craggs can dupe his corals into spawning earlier. But what is a year when you’re looking a century or millennia into the future, to a time when humanity has hopefully learnt to live with nature and not destroy it?

“If you can freeze eggs and freeze sperm you can hold the genetics of that coral down pretty much indefinitely until it’s needed in 10, 20 or 1,000 years. If we can crack this it will be as good as the day it’s frozen,” says Matson.

“We are the ultimate fall-back if all else fails,” adds Rolmanis. “For some coral reefs, biobanking them is their only chance of survival because they’re so depleted in the wild.”

Craggs talks modestly about his team’s achievements. He stresses that he works in collaboration with counterparts in many other countries, and relies heavily on grants and partnerships. But scientists and researchers now fly in from all parts of the globe to visit the Horniman aquarium and study Craggs’ work, and he regularly flies off to far-flung conferences to talk about the remarkable breakthroughs he has achieved since 2012 in his improbable base.

“I look back on what we’ve achieved in that time and it’s absolutely extraordinary,” he says. “We have so many visitors from all over the world, and they say, ‘I literally cannot believe what you’re able to do in a tiny corridor.’”