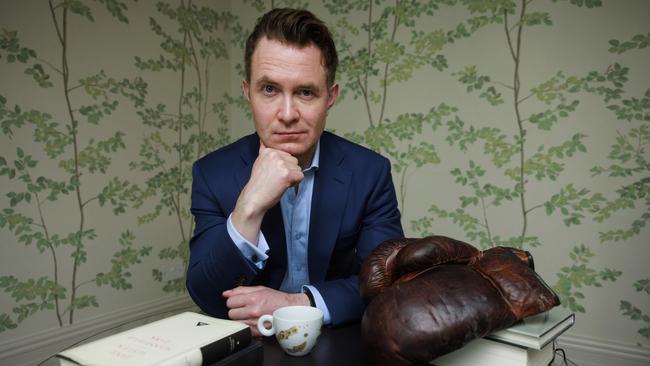

The making of Douglas Murray: ‘Most people in the West have no idea what we’re at risk of losing’

The firebrand British intellectual’s views on Islam, the West and the poison of identity politics have made him a controversial figure to the progressive left. But he refuses to be cancelled.

Light is falling on the Israel-Gaza border, where Douglas Murray is staring down the barrel of a TV camera, halfway through a live cross to London. Broadcaster Piers Morgan is quizzing the British writer and journalist on whether he believes young Palestinians will be radicalised in response to Israel’s bombardment of Gaza.

It’s a question Murray has faced several times since arriving in Israel in the wake of the terrorist attacks of October 7, but it’s one he won’t get to finish on this occasion. “Sorry, there’s an incoming …” he stutters, before repeating “incoming, incoming” to his camera crew, and diving off-screen for cover. The dim roar from a rocket soaring overhead punctures the twilight silence, and once Murray reappears on camera Morgan is keen to press the obvious: “Just before we go on, Douglas, how does that make you feel, what just happened then?”

“I mean, I’m a little used to it,” Murray shrugs in response. “I was in Ukraine last year, in Kherson, Odessa and Mykolaiv, when the Russians were shelling it so I’m used to it.” In mid-November 2022, a photo of Murray standing alongside a Ukrainian soldier in the southern city of Kherson was splashed across the front page of The New York Post, under the headline “I’ve seen how Ukraine can win”. Almost a year later, a similar image appeared on the front of the same paper, only this time Murray was wearing a bulletproof vest, striding through the blood-splattered streets of a kibbutz less than 7km from the Gaza border. The headline read: “World must not forget”.

Although Murray has raced to report on some of the hottest conflict zones in the world (he’s covered every one involving Israel since the 2006 Lebanon war), we’re not looking at your everyday modern war correspondent. Trim, sharply dressed, Oxford-educated with a cutglass accent, he is self-consciously a gentleman of the old school. Aged 19 he wrote a biography of Oscar Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, the first of his eight books. For a brief time, it seemed more likely Murray would fashion a career in classical music.

Today he writes about contemporary politics and culture in publications on both sides of the Atlantic including The Spectator, The Sun and The New York Post, and he has a weekly column on The Free Press delving into the works of great poets like Shelley, W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, Seamus Heaney and Clive James.

As one of Britain’s most erudite thinkers, he is also prosecuting a case for western liberal democracy on TV, radio and podcasts, in the face of growing existential threat and challenges from within (including the fragmenting effect of identity politics). He does so with unsparing intelligence – underscored by sometimes combative social media posts and arguments that have gone viral; a sparring match with the Palestinian National Initiative leader, Mustafa Barghouti, has been watched 4 million times on YouTube.

Murray’s position on the ramparts of the culture wars has bolstered his profile worldwide, but he is a polarising figure in his native Britain. The Guardian attacked his 2017 bestseller The Strange Death of Europe as “gentrified xenophobia”, while in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in 2015 (in which two Algerian Muslim brothers stormed the Paris offices of the left-wing satirical magazine and gunned down 12 staff) and the stabbing attack on author Salman Rushdie, Murray was accused of Islamophobia. Three years ago the 44-year-old moved to New York, where he can be found holding court among conservative intellectuals on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

To some, Murray is the new Christopher Hitchens, the late Anglo-American journalist and political shapeshifter, who was an early supporter of Murray’s work. The theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss, a friend of both men, recently observed: “Douglas is more conservative, Christopher was in some ways more liberal, but their deep reserve of knowledge combining literature and current events makes listening to either one of them compelling.”

It’s not easy to put Murray in a box. He is gay, but trenchantly against the LGBT movement; a poetry aficionado and English scholar who appals the left-wing literati. He doesn’t believe in God, but calls himself a Christian.

This month, Murray arrives in Australia for a national tour in conversation with podcaster Josh Szeps. After a number of shows sold out, more have been added – a sign of his growing worldwide profile, although Murray insists his tour is not about feeding that. “Anyone who’s a writer should not seek fame, because this is a very bad profession to go into if you just want to become famous,” an exhausted Murray says. He’s speaking from a London hotel room following an extended stint of reporting in Israel, where he has rock-star status. “It’s very moving,” he says of his warm reception in that country. But, he adds, “it’s sort of saddening to me because it suggests they feel that they don’t have very many sympathetic voices in the non-Jewish world. I think that’s terrible; it saddens me enormously.”

When talking to Murray you get the sense of a man completely secure in his opinions. There is no trace of arrogance or malice. The subjects on which he writes are rarely uplifting, but he does not come across as a lugubrious or cynical personality. In conversation Murray is warm, humorous, even playful.

While the progressive orthodoxy may demonise him, Murray delivers his arguments with clinical precision. Appearing on Britain’s Talk TV, Murray was asked by host Julia Hartley-Brewer about “proportionality” in Israel’s response to Hamas. “Proportionality in conflict rarely exists,” he said. “But if we were to decide that we should have this fetish about proportionality, then that would mean that in retaliation for what Hamas did in Israel, Israel should try and locate a music festival in Gaza, for instance (and good luck with that), and rape precisely the number of women that Hamas raped, kill precisely the number of young people that Hamas killed …”

To his enemies, Murray is a dangerous man and thinker. In response to his vocal support of Israel, a lecturer at King’s College London – during a course on counterterrorism – branded Murray a figure of the “far right” (when Murray founded the think-tank The Centre for Social Cohesion, he described it as apolitical) and likened him to American podcaster Joe Rogan. The lecturer even speculated on how to silence such people. “To deplatform them would cause issues,” he told students, “so society needs to find other ways to suppress them.”

Canadian psychologist and author Jordan Peterson observes that Murray engages in a kind of “judicial pitilessness”, in which he marshals his rhetorical powers and sends them into combat. Peterson said of his friend in a recent interview: “He doesn’t let anyone off the hook”.

Szeps, whose Uncomfortable Conversations podcast hosts figures from across the political spectrum, says he wanted to bring Murray to Australia because he’s one of the few intellectuals who can question taboos in a “bullshit-free manner”. Murray has a knack for “puncturing the self-certainties and biases that we don’t even know we hold”, says Szeps. “He flirts with subjects and opinions that are close enough to being beyond the pale among polite society” even if people may “take the worst possible interpretation of what he’s saying and frame it as if he’s not worth listening to.”

Szeps believes Australians are eager to listen to a fearless speaker who will add something “unusual, fresh and heterodox” to the national debate. “People have said, ‘When you Google Douglas Murray you see that he’s been peddling [far-right] conspiracy theories’,” Szeps says. “And when I ask, ‘What far-right conspiracy theories?’ they always say, ‘I don’t know but, you know, it’s on Google.’”

Szeps says Murray’s early critique of treatment for transgenderism in children has turned out to be prescient: “He spoke out at a time when it was incredibly toxic to discuss transgender pediatric care and now we’re in a climate where many reasonable people in the medical field feel that the way things were being done, maybe three years ago, was probably a bit ideological, and probably wasn’t in the best interests of young people with gender dysphoria. He was a clarion call at a time when it was incredibly unpopular to be saying those things … the world has continued to vindicate his concerns.”

A few days after our interview, anti-Israel demonstrators forced the relocation of one of Murray’s London speaking engagements, with reports of death threats levelled at staff at the theatre where it was to be held. Murray will be speaking at the Enmore Theatre in Sydney’s inner west, where the local MP, the Greens’ Jenny Leong, has been accused of making antisemitic remarks. A petition has already been created to stop the event. Says Murray: “I’ll speak whenever I like, and look forward to having a wonderful night with a wonderful Sydney audience”. I ask Szeps what kind of reception Murray can expect. “Let’s just say that if I was welcoming somebody who was as ardently anti-Zionist as he is pro-Israeli, we would not have the same security concerns, and that probably tells you something about the respective cultures,” he says.

Murray says he doesn’t take the social media sinkhole too seriously. Reaching for his phone, he reads aloud a text message he received that morning from a Dutch friend. “Trending today in the Netherlands,” he says (complete with comic Dutch accent), “Anne Frank, Kim Kardashian and Douglas Murray.” Asked about the vast amount of vitriol meted out to him online, he invokes a funny character created by British comedian Catherine Tate – an aggressively bored schoolgirl whose catchphrase is “not bothered”. “I ain’t bothered,” he quips. And then in his own voice:

–

“I can’t tell you the extent to which I ignore my detractors. It’s an unbelievable lack of botheredness.

–

“I always ask my friends who read online comments, ‘Why would you do that?’ Because if you walk down the street you don’t go up to the maddest person on the sidewalk and say, ‘Tell me, what do you think of my jacket?’”

He says his books will always stand as the best riposte to his critics, who he aims “to derange with my ongoing success”.

“Whenever I have a book of mine hit the bestseller list and people ask, ‘How do you feel?’ I say, ‘Well, it’s very nice and I don’t take it for granted’. But the principal reason I’m pleased is because of the demoralising effect it will have on my enemies.” These books have a common humanist theme – the importance of the individual and liberal democracy – but Murray rejects the notion that he is any kind of activist.

“I’m certainly not a campaigner, but a defender for sure, and that’s because I think most people have no idea what we’re at risk of losing,” he says. “Like fish with water, a lot of people in the West just think this is a normal state of affairs. That you get up in the morning, you get a cappuccino, you bitch about your phone not having charged overnight and you start the day. This is not the normal course of human life in the world now – or historically.”

Murray, who refers to himself as gay in his 2019 book The Madness of Crowds, has infuriated the progressive left with his contempt for identity politics. In The Madness of Crowds, he railed against the idea of homosexuality being included in the sphere of group identity and activism, and declared that homophobia had in fact mostly disappeared across the West.

“I thought the whole point of gay rights was that you’re the same as everyone else, not different,” Murray tells me, before pointing out that he doesn’t enjoy the company of people who “do special pleading” – a “very unattractive” trait. In fact, he says, individual “rights” have superseded the idea of “responsibilities” across western culture. “You see it with things like ‘I know my rights’, ‘Give me my rights’,” he says. “[But] in vast swathes of the world, rights are taken away just like that, and you’ve got no one to moan to. Nobody cares. And people in the West have forgotten that.”

Covering wars throws this into sharp relief. Microaggressions don’t work in war zones – or at least aren’t paid much attention when there are “actual aggressions happening”, he says, adding that in Israel, few are worrying about trigger warnings or misgendering people at the moment. “It’s not worth having a war to stop that shit happening, of course, but it is true that it clarifies everything … Whereas in Australia and Britain you’re constantly scooping up horse manure across the entire highway of public life.”

Murray’s most recent book, The War on The West, argues that it is the marauder within – a powerful amalgam of activist academics, politicians, historians, educators and large swathes of the media – that has inflicted the most grievous damage on the West. This has, he argues, forced the fragmentation of society by slowly chipping away at the edifice of traditions, history, culture and institutions that were the original drivers of prosperity, self-confidence and emancipation. “We appear to be in the process of killing the goose that has laid some very golden eggs,” he wrote.

I put it to Murray that his writing over the years about the causes of Western decline and defeatism has turned out to be prescient, especially today. But he doesn’t see himself as doomsayer, even while criticising the response to Hamas’s October 7 attacks from countries such as Australia and Britain. “The fact that Australia’s first Muslim minister [Ed Husic] would be so vociferous on the question of Israel is incredibly predictable and profoundly depressing – because it’s the same everywhere,” Murray says, after unloading on Australia’s “disgraceful” decision to support the UN call for a ceasefire at the end of last year, while Israeli hostages remained in Gaza. The First Minister of Scotland, Humza Yousaf, is another politician who draws Murray’s ire, described as a leader who “spends most of his time talking about Gaza and not about the poverty and destitution in the east end of Glasgow”. (Murray refers to Yousaf as the First Minister of Gaza.)

“I think what we’re clearly seeing here is that a lot of politicians in Australia and Britain are effectively swappable,” Murray says. “You and I could organise a surprise exchange program for members of our governments, the Labor government in Australia and the Conservative one in the UK. You could lend us a foreign minister and we can lend you a foreign secretary. It will be a week or so before anyone notices.”

Murrayand his elder brother were raised inLondon, their father a Scottish civil servant and their English mother a teacher. By all accounts he was a precocious child, and seemed more likely to forge a career as a composer than as a polemicist. In Murray’s telling, music was his first love – words came later. For two years during school he was a junior at the Royal Academy of Music, as well as a chorister at St Margaret’s, in the grounds of Westminster Abbey.

Murray describes a humble and secure middle-class upbringing; he says his parents were religious but not political people. They came from a culture that valued “keeping your head down and not making much noise”. They weren’t “pushy types, either, like some modern parents”, a point Murray seems keen to stress. And yet political debate flowed freely over the dinner table, where he first learnt to hold and defend an argument, sparring with his parents over politics and current affairs. Then there were the early encounters with books and music; these, he says, were transformative.

Murray was raised Anglican but left the Church in his late twenties. In a 2009 piece for The Spectator, he wrote that he stopped being an Anglican after reading Muslim texts and deciding that no book – of any religion – could claim infallibility. He now describes himself as a Christian atheist, often referring to theologian Don Cupitt’s line: “You may call yourself non-Christian, but the dreams you dream are still Christian dreams … You may consider yourself secular, but the modern Western secular world is itself a Christian creation.”

Murray attended the local state primary and secondary schools, including one that he describes as “an inner-city sink school”. Then, at 15, he won an academic and music scholarship to Eton and three years later, a place at Magdalen College, Oxford, studying English. By 1998, the year he matriculated at Oxford, his life as a writer was already taking off. He had completed a first draft of his biography of “Bosie” Douglas, the object of Oscar Wilde’s passion, during a gap year teaching in a remote castle on the Scottish coastline.

When it was published, the biography won high praise from the literary establishment on both sides of the Atlantic. The New York Times ran a swooning review of the book under the title “Golden Boy” followed by a short piece profiling its young author. “The biographer should not take precedence over the subject, but this is an exceptional case,” wrote critic and author Miranda Seymour. The British press was equally in thrall to the talents of the 19-year-old, who was now regularly introduced as “the youngest biographer in England”.

But it was a review from Hitchens, enthusing over “the emergence of a fresh new author who bears watching”, that attracted the most attention. For Murray, though he didn’t know at the time, it was an act of literary benediction.

Murray’s evolution from youthful biographer to hardened polemicist was swift and vertiginous. Like Hitchens, who would go on to become an important friend and mentor, Murray learnt early how to wield his pen as paintbrush and rapier.

In 2011, three years before gay marriage was legalised in Britain, Murray set out the conservative case for it in a column in The Spectator. It was picked up by then prime minister David Cameron, who used it as the basis for his first speech in support of the change. Murray’s short piece ended with these words: “The religious case against equal rights can – and probably will – be argued till the end of time. But the effort to deny equality to members of society on shifting religious grounds and non-existent practical ones is a war on decency as well as on conservative sense.”

Murray isn’t married. When I ask if he has a partner, he responds: “I never talk about my private life because I believe it’s dangerous terrain, mainly because it reveals too much about my own whereabouts,” he says. That’s fair enough: Murray remains the subject of regular death threats and is required to report the more credible ones to police. Following his criticisms of Islam in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre police told Murray not to speak in public for a time.

Like Hitchens, Murray’s acerbic mettle is at its strongest when his speech and writing are threaded with references to history, literature and art. In his “Things Worth Remembering” column, which appears every week on independent website The Free Press, Murray reflects on his favourite poems and passages of prose, drawing connections between great poets, their writing, and the Zeitgeist.

Murray shares a fierce intellectual contempt for the new political correctness with Bari Weiss, who set up The Free Press after she sensationally quit The New York Times in 2020, declaring it a hostile environment lacking in political diversity. The poetry column, says Murray, was Weiss’s idea. “She said, ‘I want you to do something different from your other writing’ and she came back with this idea. She said, ‘Whenever I’m on stage with you or at dinner you pull these things out of your memory with alarming ease, so why don’t you write about the poetry you have in your head?’ Which was a wonderful idea and I’ve loved doing it because I’ve rather unselfconsciously at the beginning and then more consciously throughout my life read certain things and thought, ‘Ah, I want that, I want that to stick. I’m going to need that’. And it’s proven to be the case.”

When I ask Murray whether he envisioned a life as an intellectual firebrand and sometime war correspondent, there isn’t the sense that much of this was planned out. He attributes his meteoric career rise to having a “version” of where he wanted to be in his head.

“I knew I wanted to throw myself into the subjects of my time and put my boots on and jump in with both feet. I’m flexible enough in my life to be able to move around. I wasn’t expecting to spend so long in the Middle East, but sometimes you have plans and they get thrown out because something more important takes over. Who knows, maybe, if New Zealand invades Australia, I’ll be over there living with you guys,” Murray says, smiling.

It no longer makes sense to refer to Murray as the enfant terrible of British journalism, but nor does he appear to have reached the summit of his powers. Certainly, there is no sign of a career plateau or pause. He measures life’s progress through the books he’s written and the ones he plans to write. So what’s next? “Well, it’s still too early to say,” he responds.

For one of his poetry columns, written from the frontline in Israel, Murray wrote about Siegfried Sassoon’s poem Everyone Sang, composed at the end of the First World War. “Even when he saw the war as futile and pointless, he still threw himself at it,” wrote Murray. “But I cannot help thinking he was doing it to throw himself against the world.” b

Details: Uncomfortable Conversations Live | Douglas Murray & Josh Szeps in Conversation

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout