The last taboo: Inside the mind of a suicidal mum

Perth mum Nicole Watts shares her extraordinary and brave story of motherhood and mental illness. What’s it like for her to parent while living on the edge?

How do I begin to tell you the story of Nicole Watts? I can start with the morning she ushers me into her loungeroom balancing china cups and a teapot on a wobbly tray. I can begin with her murmured apology as she scoops up a jumble of toys to allow me a seat on her sofa. Or I can offer an image of a gentle-faced woman in a blue floral dress, tethered to life by a thread, a precarious existence teetering between not wanting to live and not wanting to die.

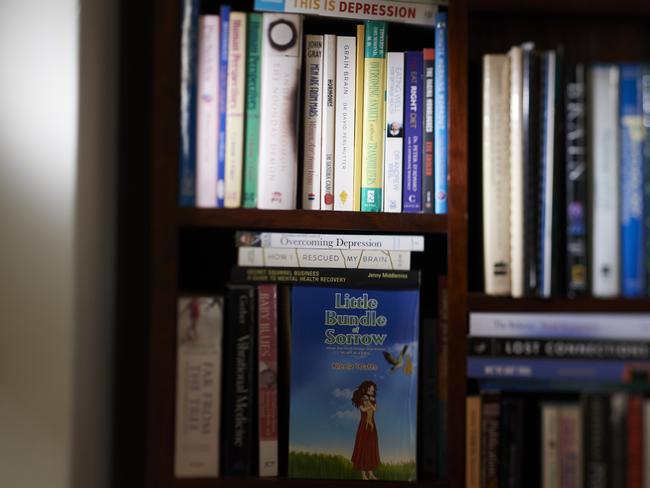

Nicole is 46, and a mother to two boys aged 12 and nine; she has a Bachelor of Psychology and was formerly a manager at the Australian Bureau of Statistics. She lives in a neat brick house in Perth’s northern suburbs on a street with a Catholic church at one end and a Mormon temple at the other. She leads me past a piano loaded with sheet music. I’m intrigued by her ceiling-high book collection, batched by subject – neuroscience, true crime, philosophy, the Romantic poets, modern fiction. She tells me reading is her salvation, a distraction from the soul-eating depression that has compelled her to make countless attempts on her life.

“I think I understand what it means to be human more than most, because I live on the edge of death so often,” she says. “At my lowest, I can’t talk. I can’t cry. I don’t sleep for days. I hallucinate. Everything hurts. My grief and distress is so overwhelming I’m not capable of imagining what my children will go through after I’m gone. All I can think about is the bliss death will bring. I’m just glad for my kids’ sake I’ve failed so many times. Because when I’m well, they’re my whole world.”

Nicole Watts does not shy away from discussing her wish to die. She does, however, bristle at the suggestion that suicide is an act of will: the trigger pulled, the pills swallowed, a rope knotted, a knife sharpened, the fall from a great height. Rather she considers her many attempts on her life as low points in a deep-rooted illness, beginning when she was 18. She traces its origins to trauma and isolation, to violence and neglect, to the loss of love and belonging, ravages largely hidden from others.

“I grew up pretty fast. Dad was a landscape gardener who later gambled away everything he had. Mum left school at 14 to help support her own single mother. I was an only child until Mum remarried and I inherited a younger step-sister when I was 7. It was a volatile household. There were violent confrontations between my Mum and my step-dad. I never learnt to sleep. I was too anxious. But I was an A-grade student at high school. I moved out of home at 17 to be with my childhood sweetheart. Took my first overdose at 18 after we broke up. Swallowed a whole bottle of sleeping pills. I’d gone ‘doctor shopping’ and saved up ten Valiums, so I took those too for good measure. Threw in a packet of Panadol just to make sure. I should’ve died on a quarter of that. I just remember Mum waking me up and I was just so disappointed I hadn’t succeeded. By the time I was 27, I’d tried to drown myself in the bath, cut myself to bleed out, starved myself to under 40 kilos – anything to escape the devastation inside my head.”

On the day we meet, Nicole is a few weeks post-discharge after two months in a private psychiatric clinic. She says her failure to die is her greatest achievement, after her children. She’s endured critical bouts of post-natal depression, a marriage breakup, repeated hospitalisations, a welter of medications, three rounds of electroconvulsive therapy, recovery and relapse. The electroconvulsive therapy – tiny electrically-induced seizures, triggered under anaesthesia, to reset the depressed brain – has drilled permanent gaps in her memory. “I keep a diary,” she says. “I can’t remember the kids’ last birthday parties. Or the holidays. I didn’t realise how much of my self-worth was tied to memory.”

She has wounds on her hands, stomach, feet. “Sometimes my boys see the scars and they’re curious. I say I slipped in the shower. I say I fell over. I get so annoyed when people say suicide is selfish, because in that extremely depressed state it seems that life is so bad, so terrible, that dying is the only way out. My thoughts are so disoriented that suicide becomes the logical, rational option. I’m not thinking about what will happen when my boys find me dead. I’m not thinking about them at all. I know they’ll be looked after by their Dad, by my Mum.”

Nicole is adamant that her suicidal ideation is a disease process, not a choice, a wish, a decision or a message to the living. “I cling to what my psychiatrist told me, that a bad mother is better than no mother at all. I don’t think I’m a bad mum but I have to recognise there are times when I need to be away from my children for my own safety. I’m trying to process that in a positive way, because I know I’m getting help so I can look after my children. I cry when I leave them. I cry when they come to visit. I carry immense guilt. At school, other mothers don’t know what to say to me. So they don’t talk to me at all. I feel shunned. They’re drinking green tea and giving their kids sushi for lunch and I’m deciding whether to live another day.”

Today, Nicole’s breakfast is a fistful of pills. Yellow, blue, white, pink – a pastel roulette of mood stabilisers, stimulants and three powerful anti-depressants. She’s an obedient servant to her drug regime, counting down the hours to the next lot of pills. At night, she takes a battery of sedatives to sleep. Mornings she wakes befuddled and dazed, needing dexamphetamines to jump-start her day.

For the chronically depressed, time turns in warped circles while the rest of the world barrels ahead in a straight line. “Most people take their todays and tomorrows for granted. Not me,” she says. “I’m a survivor of suicide. People ask me about my attempts to commit suicide and I correct them and say, ‘I didn’t try to commit a crime.’ Even the language we use is deceiving. Suicide is not a crime and it’s not a sin. It’s a last-ditch attempt to escape the emotional pain of being human.”

For hundreds of years, doctors have tried to understand why our minds would hurt us. Even modern medicine has been unable to deliver wonder drugs for mental illness. The drawbacks start with the intolerable side effects. The depressed brain is renowned for its unwillingness to return to an even keel. Like childbirth, chronic depression can only be experienced, not explained. It’s a sinkhole that engulfs every pleasure, every comfort, every moment of peace and fulfillment, trapping its sufferers inside a pit of despair.

It seems that society has a particular distaste for mothers who want to die. Apparently, abandoning your children by suicide is only an unforgivable sin when women do it. “When a man kills himself,” Nicole says, “no one questions his fathering ability. They say, ‘It’s tragic he’s left his kids behind,’ but they don’t ever say he was a bad dad. If you’re a mother and you suicide, all the good mothering you’ve ever done is negated. Your callousness wipes the slate clean.”

Nicole Watts’ story is a bleak love letter to every mother who has struggled to do her best. She’s the poster girl for mother-guilt in a world that still expects women to be the tireless protectors of their children. Absorb the strain, we mothers are told. Take it. Take it all. We try – and fail – to be perfect mothers. We’re suffocatingly present or dismissively absent. We’re too pushy. Or not pushy enough. Mother-guilt tunnels through sleep, leaving us anxious and drained. We sacrifice, console, cajole, nourish, cherish, guide, shelter, and love, year after year. So why do we agonise? Why do we not acknowledge that mothers can only stretch so far before they break?

“There’s just no understanding of what a mother with mental illness goes through,” Nicole says. “It’s a terrible barrier to friendship. Other mums are scared of contamination, that I might make them crazy. All they can say to me is, ‘Oh Nicole, you look great.’ Like I’ve just had a bandage removed. I come out of hospital and I’m ostracised and alone. Frankly, it’s a relief when I go back inside. In hospital I’m with my tribe. We’re all trying to stay alive, dealing with the side effects from our meds. When you’re mentally ill, you’re so much more tolerant of other peoples’ demons and faults and flaws. You’re pretty understanding if someone cancels a coffee date.”

Nicole’s illness has created a jagged backdrop to her family dynamic. Her ex-partner, a FIFO miner, shares custody of their children. Nicole’s mother, 81, and her stepfather, 76, step in when she’s admitted to hospital.

“The boys’ve been staying with us on and off since they were babies,” says Nicole’s mother. “They’re like a tornado coming into the house, but when they leave us it’s like a morgue. I must admit I do get a bit tired.” She laughs. “But I’m in good nick. We take it day by day. We’re always here for the boys. They know their Mum has to be in hospital sometimes.”

Nicole’s mother says she doesn’t know the root causes of her daughter’s illness. “As a kid, she was quiet, always the perfectionist. I remember one of her teachers in high school telling me she was ‘wound up tight’, but my girl never gave me a day’s grief.”

It’s hard to imagine the energy required to be parents-by-proxy late in life. “There are grandparents out there doing it way harder than us,” she says. “My daughter is sick, but her children are not suffering because their Mum has a mental illness. I tell you, no one gets a perfect mum.”

Since psychiatry hailed itself a profession two centuries ago, women who’ve failed to cope with the expectations and realities of motherhood have been diagnosed as mentally unwell. Mad, neurotic, deranged, insane, highly strung, paranoid, disturbed. “Hysteria” still stains the way we describe and pathologise everything mysterious or unmanageable in women. We tell mothers to be selfless, yet no mother can maintain an impossible ideal. At times, helplessness blankets us all. Two of my closest friends – smart, capable women – are haunted by intermittent depression. In conversations, we regularly swap notes on how we might be flunking motherhood. We turn to each other for reassurance we are not “bad” mothers, that “good” mothers don’t always put their children first. Our phone calls underscore the fear our deficient mothering will scar our kids for life. We agree we’re only ever as happy as our unhappiest child. Few mums deliver their children into adulthood without a wobble along the way. But for some, the trickle of sadness becomes a haemorrhage, flooding everything. At the extreme end of mental illness, the suicidal mother lives in a halfway house between not wanting to live and not wanting to die.

“Having a baby is psychiatrically the most dangerous thing you can do as a woman,” says one Perth psychiatrist. “One of the biggest predictors for post-natal depression is an unsupportive spouse. We know single mothers report higher levels of anxiety and depression than partnered mothers except, not surprisingly, when that partner is unsupportive. Never assume motherhood is a protective factor against suicide.”

The literature on mothers who take their ownlives is sparse, not least because of an over-reliance on large datasets showing the higher prevalence of suicide deaths among men.

Last year, a Macquarie University study analysed the case histories of 31 young Australian mothers who took their own lives. Of those, 61 per cent had been victimised, most by a partner; 32-per cent of the deaths involved alcohol or drugs. A number of the women blamed themselves for circumstances beyond their control. The study concluded that mentally distressed mothers often won’t seek help, for fear their children will be removed. It lamented the hypocrisy of expecting women to maintain good mental health for the benefit of children when the demands of mothering preclude any time for self-care.

Nicole’s story is unflinching testimony to an illness long shrouded in silence, whose stigma heightens under conditions of isolation, loneliness and shame. She says platitudes are useless. “If someone is depressed, please, please, have the hard, uncomfortable conversations. Tell them you’re in their corner, that their darkest thoughts will pass. Tell them to hang on, because tomorrow will be different. Next week will be different. Next month will be better.” She leans towards me and lowers her voice: “And if they have a sudden mood upswing, act fast, because they’ve probably made a plan to die.”

Lifeline 13 11 14; beyondblue.org.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout