‘The English think Australians are only good at sport’: Georgie Black’s mission to defeat cultural cringe

Philanthropist Georgie Black is determined to give Australian artists and performers the international recognition they deserve - and she’s prepared to bankroll the cause herself.

Annabel’s in London’s Mayfair describes itself as “one of the most elegant clubs in the world”, and is feted for being the only nightclub attended by the late Queen Elizabeth. It’s the exclusive venue where Taylor Swift hosted a morale-boosting wrap-party after cancelling three sold-out concerts in Vienna due to a terror threat. A nubile Diana Spencer used to dance barefoot there, and there’s some lore about a tanked John Wayne tweaking a stranger’s nipple at the bar. So when Australian barrister and philanthropist Georgie Black invites you to lunch – she is a member – you say yes. But you probably shouldn’t wear trainers.

There’s an awkward encounter with a Dolce & Gabbana-clad hostess – “we will make an exception for your guest this time, Ms Black” – before we’re escorted past the cantilevered staircase and long Rococo bar out to a glass-ceilinged garden terrace where sheikhs mingle with oligarchs amid lush ferns, cascading vines and opulent furniture. It’s quite a scene. Instinctively, I take my phone out to capture it, but there’s a gentle tap on my shoulder. “No phones allowed,” says a waitress.

Georgie Black is unfazed. She has an insouciant air as we sit down to discuss her philanthropic initiative, House of Oz, which pays for Australian performing artists to participate at major international events, most notably at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The artists she platforms refer to her as their “fairy godmother” and I’ve heard her described as “a one-woman Australia Council”. So when she asked me to travel to London and Edinburgh last August to see what she describes as “the mission” for myself… I said yes.

“Every year I clear out my bank account to bring Australian acts over here,” Black begins. But before we can really get into it, the hostess is back. She’s decided that I might feel better about the shoe faux pas if I “twirl” to show off my “fabulous outfit” (I had enough nous to pair the trainers with a suit). I reluctantly pull off a self-conscious manoeuvre, but when she asks the same of Black, a former ballerina, she’s met with a polite “I’m OK, thanks” and the slightest hint of a curtsy. “I don’t need to twirl,” Black whispers to me. Note to self: one does not tell Georgie Black to twirl.

The accomplished barrister, who is also a former actor / yoga teacher / opera singer / stand-up comedian / travel writer, now very much focused on philanthropy, is not your everyday multihyphenate. The wife of Graham Edwards, entrepreneur and treasurer of Britain’s Conservative Party, her project to promote Australian acts on the world stage is now in its fourth year.

Since its inception House of Oz has produced more than 1000 shows. In its first year, it won best festival venue at the EdinburghFringe. In 2022, Black was a patron of the Australia/UK Season of Culture before going on to work as executive producer on Knowing the Score, a documentary about conductor Simone Young (described in The Australian as “absorbing ... demands an encore”). House of Oz assistant produced the UK season of Yve Blake’s smash hit Fangirls at the Lyric Hammersmith and executive produced two documentaries on Adelaide circus troupe Gravity & Other Myths. In 2023 House of Oz invested in the West End musical Pavarotti directed by Michael Gracey and supervised by five-time Grammy award-winner Jacob Collier.

In addition to working on the 2025 season for House of Oz (she is collaborating with Circa, Opera Australia and Opera Queensland to bring Orpheus and Eurydice to the festival) she is now producing a documentary on Lewis Major, a South Australian/Jewish/First Nations former sheep farmer turned contemporary dancer and choreographer.

“I have an income and I put it all towards House of Oz,” she tells me. In its first year, House of Oz spent one million pounds on the Edinburgh “experiment”. The second year cost a further million. In 2024 Black partnered with Assembly Festival, the longest running multi-venue operator at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, which cut 75 per cent of her outgoings (it costs roughly £30,000 [$59,000] to transport, house and support each act at Edinburgh, and in 2024 she brought over 12 acts). “The plan now is to be joined by other philanthropists, other donors, people who believe in the mission,” she says.

It’s a lot of time and an eye-watering amount of money. I have to ask, why does she do it? “The English think Australians are only good at sport,” says Black, who has lived in England since the early 1990s. “But Australian artists are ebullient, colourful, witty and vivid – and don’t get the international recognition they deserve. I want to show Australian culture to the world!”

She notes the “cultural cringe” directed towards Australians by the English and I ask Black if she’s ever felt denigrated by a Brit for being from the Antipodes. “I think Graham [her husband] made a speech at our wedding in which he said, ‘Australian culture… is there even such a thing?’” And now he co funds the mission? “Yes,” she says with a smile.

The night before Black and I leave for Edinburgh, Australia House fills up with expats, dignitaries and performers, sipping on House of Arras sparkling wine and eating technicolour lamingtons to celebrate the launch of House of Oz. Representatives from Number 10 mingle with drag queens and comedians. I spy Kathy Lette chatting to the playwright Hilary Bell, whose trio of short plays Summer of Harold will have me weeping in an Edinburgh theatre a week later. When Michael Dalton, performing as drag queen Dolly Diamond, takes to the stage he exhorts the High Commissioner, Stephen Smith, to bestow a kiss upon his cheek. Smith acquiesces and his staff, seated beside me, try to conceal their guffaws.

“What Georgie has done is the result of her own endeavours, philanthropic work, and commitment and desire to see Australians successful in the UK,” Smith says, as he declares the House of Oz open.

A cynical person might be tempted to pass Black off as an aesthetic dilettante with a large wallet — there are her own earnings and those of her husband, who has co-founded heavy-hitting companies across real estate, commercial water, online fashion, engine development, and data analytics. But she says her experience dabbling in so many different artforms has left her uniquely well-equipped for her work as a philanthropist in the arts.

“What it means is that I am very well suited to what I do. I can tell what is fantastic art when other people do it. And I don’t think about it as work. It’s my mission.”

Black, the daughter of two doctors, credits her upbringingfor her voracious appetite for culture. When we meet at the home in Hampstead which she shares with Edwards and their blended family of four children (the couple split their time between London and Sydney), she stretches out on the lounge wearing a flowing pink dress, her bare feet crossed at the ankles. She has a remarkable mane of curly blonde hair that tangles down to her waist and she speaks in a rapid-fire manner – eloquent and razor-sharp but also meandering, the conversational equivalent of running through a maze. She doesn’t drink, has been vegan for 30 years, and is up at cock’s crow every morning for pilates, yoga or kickboxing. She had her second child, Remi, who sits beside her flicking through books for the duration of our interview, at 47.

“Being passionate about the arts ... was instilled in me from an early age,” she says. “I’ll never forget my first opera. I was 15 when I saw Carmen at the Arena di Verona [in Italy], sitting on the pink granite that had been warmed by the sun all day. There were live elephants on the stage. The acoustics were perfect.”

Like her mother and aunt, Black attended the private girl’s school Kambala in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, where her love of the arts was fostered by the school’s focus on drama and music. She went on to a Bachelor Degree of Arts/Law at Sydney University but says she “hated the law” and spent all her time with the Sydney University Dramatic Society. “At the time, there was Marion Potts, Patrick Nolan, Andrew Upton, Sacha Horler, Lucy Bell and Miranda Otto,” she says. When she played the lead in Sleeping Beauty, Miranda Otto played third fairy; Lucy Bell (a firm friend) played her mum.

While Black initially pursued acting professionally, she says a number of “bifurcating moments” led her towards a career outside of the arts. One was in 1991 when it was down to her and one other actor for the lead role in what she calls the “terrible film” Exchange Lifeguards. (I google it; oh dear.) She didn’t get the role and moved to London with “no regrets”.

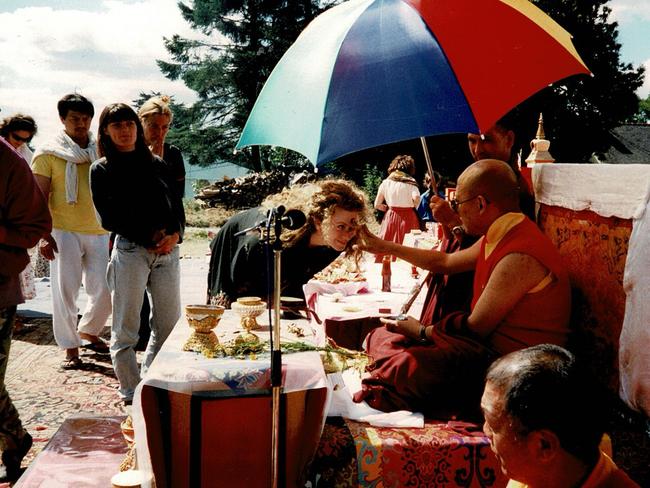

In London she waitressed, bartended, worked as a travel writer under a pseudonym, had a go at stand-up comedy, trained as an opera singer and sang with a troupe that set Brechtian short stories to arias. She was on her way to becoming an opera singer, struggling to afford the 40 pounds a week to pay her singing tutor, when “my guru told me to go back to study law”, she says. Black is Buddhist and has travelled to India ten times, including a spell living in a monastery in the Himalayan foothills. There’s enough fodder in the stories she tells me about this period of her life to make a good memoir. But is she sad that she didn’t end up working as an actor? Or a comedian? Ballerina? Opera singer? “Somebody once said to me, ‘Your life is the manifestation of your true desires’. In other words, if I really wanted to do it, I would have made it happen,” she replies. “I think I had absolute tenacity as a barrister, but I didn’t have bravery and courage in relation to my own creation of any particular art form ... I felt its power and beauty, but how good was I? Not that great.”

We travel to Edinburgh and I notice that Black almost always has one of her two daughters, aged 13 and nine, alongside her while she works. She carries an enormous blue Stella McCartney handbag full of notebooks, flyers and passes. I shoulder it at one point and understand why she takes so many taxis. Her days are hectic and the children roll with her as she flits from tech rehearsals to show previews to spontaneous meetings with new artists. At one point she gets a call to say that actor Alan Fletcher, aka Dr Karl from Neighbours, is passing through town with his alt-rock country band and is eager to meet her. She acquiesces and jokes that she is tempted to get him to look at her sore elbow. Not once do I see her daughters on a technological device – they listen, read, contribute, and doodle in their journals.

Over many (vegan) lunches, we discuss how the acts are progressing. Three sell out their first few nights immediately, but there are teething problems. There’s a “noise bleed” from a neighbouring theatre and the incongruous strains of The Proclaimers’ I’m Gonna Be… can be heard over the opening moments of actor Michaela Burger’s one-woman show about a sex worker; Dalton (Dolly Diamond) has absconded from his accommodation after declaring that he “doesn’t do pods”; and one performer’s child needs an emergency appendectomy.

“I’m still learning and getting things wrong,” Black says, as we creep through the crowded streets of Edinburgh in the back of a black taxi. She points to where the pavilion was in previous years and reflects on the cost saving and the benefits of having her acts spread across the festival in venues that suit them better. She tells me that in 2023, the pavilion had its own pop-up bar and cafe serving ’roo burgers and Passiona, and the exterior was bedecked by one of artist Lisa Roet’s giant inflatable gibbons.

“Oh, yours was the one with the giant monkey in it,” interrupts our taxi driver. “I have a photo of that on my phone!”

“Bless your heart,” Black says, and stops our conversation to organise tickets for him to see a show. In yet another taxi ride, while we are discussing Michelle Pearson’s show Down Under: The Songs That Shaped Australia, Black interrupts herself to yell, “Do you like Australian bands like Cold Chisel and INXS?” When our driver replies that he does, “very much”, she whips out her phone and puts his name on the door.

“I don’t think for one moment Georgie went into this thinking that she knew everything,” Dalton tells me. “From the first year it was obvious that she threw a lot of money at this project. And that’s entirely because of Georgie’s love for the arts. Knowing the right avenues for the money was maybe a little misguided in the beginning but it’s been streamlined. She has always asked the artists to tell her what works and what doesn’t. And she applied almost everything that we said.”

Most of the House of Oz acts will go on to sell out their runs over the month-long festival, resulting in over 80 offers of onward touring. Lewis Major will receive 34 expressions of interest for his show Triptych, and, according to Black, is “on his way to superstardom”. And the mission is growing beyond Edinburgh. This year, House of Oz will travel to Brazil for a one-week festival in São Paulo, and several acts will perform at the Bradford City of Culture Festival.

Black also notes that House of Oz artists tend to enjoy more success in Australia once they have success abroad. In 2024 many of her acts came back from Edinburgh to sell out shows and win awards at the Sydney Fringe Festival.

“Australians are even more guilty of the cultural cringe [than the English], and House of Oz proves that. We give a lot of artists success overseas and then they’re welcomed back like homecoming heroes. Instead of fighting against that I do my best to just go with it and help these artists by giving them this platform overseas, which then augments their careers once they get back home.”

Does she ever make money off shows? “God no. The idea is just to give,” she says. “There will be some artists who make money, and then it’s a circular economy, and it comes back to other artists who won’t...But ultimately, it’s giving,” she says. “I’m not expecting to get the money back.”

Over drinks in the Assembly Festival Bar, Adelaide comedian Yoz Mensch tells me about the “immeasurable” support they have received from House of Oz. “In order to come to Fringe you have to set yourself backwards. Knowing that there is this entity – Georgie and the House of Oz – that believes in me is so motivating. It means I can come to Edinburgh without worrying that I’ll never be able to afford rent or to eat when I get home. The last time I was here was in 2018 and I have still not recovered financially.”

The Listies, who draw the largest crowds of all the House of Oz acts, are an Australian “kidult” duo beloved by both adults and children for their delightfully silly, potty-humour-laden comedy. Their show, Hamlet: Prince of Skidmark, was the first act Black ever brought to Edinburgh. “I emailed them cold and told them what my plan was. And they were like, ‘That’s the best email ever’,” she recalls.

“This is where the world of performing arts is,” Richard Higgins, one half of The Listies, tells me. “But to get here… I don’t know how new and emerging theatre makers do it now. Flights are twice what they used to be, accommodation is five times what it was. And there is no support for artists to get here. It means an enormous amount to have this incredibly generous support from Georgie. Working in the arts is precarious… Georgie takes the precariousness away.” In order to travel to Edinburgh every year, The Listies would go into thousands of dollars of debt. In their best year, they came away with a profit of £300 ($600) each for their month-long season. The Listies described their 2024 season as a “landmark success. We pretty much sold out our entire run”.

As well as travel and housing, House of Oz also provides many of the acts with extra production and technical support, marketing services, advertising support and negotiations with media and venues. “These are all things that cost artists time and money,” Matt Kelly from The Listies says. “With the incredible help and support House of Oz have given us we are now in a position to do a return season of a show at Edinburgh 2025, something we have never done in our decade of performing there! Plus House of Oz are assisting us in expanding the tour in The UK to make it even more worthwhile.”

![“Australians are even more guilty of the cultural cringe [than the English].” Picture: Nic Walker](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/6cdda9d123fa4536eda542a03ee54c20?width=650)

I overhear an acrobat from Gravity & Other Myths (which will go on to win four awards at the festival) introduce Black as their “sugar mummy”. And on more than one occasion she tells me that she thinks of the artists as “like her children”. What all the artists I speak to seem to agree on is her lack of arrogance. One day, when I meet her in the bar of the Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh, she waltzes in and smiles to reveal electric blue teeth. When I tell her that her teeth are very blue and ask what she has eaten, she replies, “Cherries. Let’s go!” We haven’t known each other for more than a few days but it’s long enough for me to insist that she return to her room and look in the mirror. From then on, she refers to the hotel bar as the Blue Teeth Bar.

Black and her family spend the full four weeks of the festival in Edinburgh. In the mornings they hand out flyers for the shows that need the most support. They attend performances throughout the day and late into every night. Over the five days I spend there I’m astonished by how indefatigable she appears.

There are only two occasions on which I see her fade. One is at 1am, while we watch South Australian cabaret star Jonny Hawkins perform his show, Dancefloor Conversion Therapy, about his journey from Christian youth-minister-in-training to queer party icon. The show will go on to be a success, selling out most dates in Edinburgh, raking in awards at Sydney Fringe, and being approached to be the subject of somebody’s PhD. I glance at Black and notice that her eyes are closing. It’s not an indictment of the show, which is very high energy, but it’s been a long day. It’s late, so I don’t rouse her.

The other occasion I recall is on the day of our first meeting at Annabel’s. After lunch she is keen to show me the ladies’ bathrooms, which, with their pink marble basins and flower-festooned mirrors, are like the setting for a high-end hens’ night. As we wash our hands Black tells me that she is tired and doesn’t have time between lunch and her next engagement to go home for a nap. She eyes a long bench, with a row of mirrors and chairs, where guests can touch up their makeup.

“I wonder if I could lie under there and have a ten-minute sleep,” she muses.

We pull back the chairs and she crawls underneath, stretches out on her back, sets her phone timer for ten minutes, mouths the word “goodbye” to me, and closes her eyes. Her long golden curls fan around her, halo-like. I tuck the chairs in to conceal her as best I can, tiptoe away, and shut the bathroom door as lightly as possible, looking around to make sure no Dolce & Gabbana-clad hostesses are on patrol. This fairy godmother needs her sleep.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout