The day archaeology changed forever

Archeology changed forever on a day in June, 1995. Now, thirty years after ‘The Battle of the Bones’ granted Indigenous Australians influence over the remains, art and artefacts of their ancestors, what has been gained and what has been lost?

You can now listen to The Australian's articles. Give us your feedback.

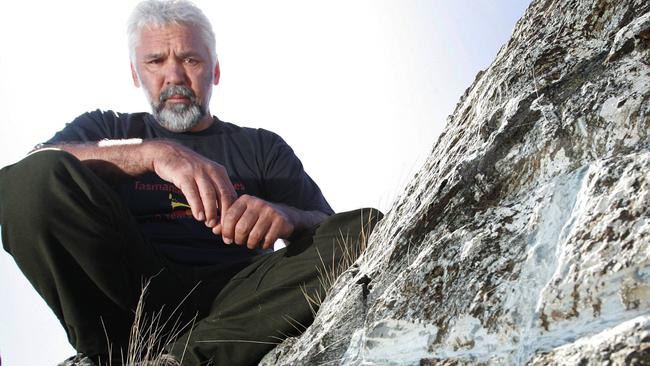

Tim Murray doesn’t recall much of the detail of that wintry day in June 1995 when La Trobe University took the unprecedented step of bolting the doors at the school of archaeology and sending the students home. It was a heightened response to rumours that Aboriginal activists were preparing to drive a truck to the Melbourne campus and reclaim thousands of shells, animal bones, faeces and glass Aboriginal tools laid out for analysis at the school’s lab. What Murray does remember very clearly is being served with the Federal Court writ accusing him of illegal possession of that material, taken from caves in Tasmania between 1987 and 1991.

Karen Brown remembers that writ too. A month after Murray, as head of school, had closed the school for security reasons – he wanted to protect other precious archaeological material – Brown was in court to hear a decision that would change the relationship between archaeologists and Indigenous Australians and the way we investigate the past. Brown, at that time the administrator of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Land Council, was “thrilled”. Her colleague at the Council, Rocky Sainty, was “ecstatic”. The Indigenous leaders had denied that any raid had ever been planned at La Trobe, but now they had a legal ruling that the university must give up the “relics”. They knew it was a remarkable victory.

Murray, on the other hand, was “mystified” by one of the more consequential decisions ever made in this country for First Nations people. Justice Howard Olney’s order for the surrender of about 130,000 artefacts was a historic turning point, one that altered the trajectory of archaeology in Australia and set in motion an approach to Indigenous culture that still makes headlines today.

Thirty years on, many of the players have forgotten the details of events that would be reported later as “the battle of the bones”. But everyone remembers this as a pivotal moment in the question of who owns the past, and who controls access. Rocky Sainty says: “It was an overwhelming decision for the community because up until this happened, we had no say whatsoever in who came in to do work. We were just tired of our sites being destroyed. It took a little while to sink in.”

Tim Murray recalls being “absolutely trashed” by colleagues in other universities for fighting the repatriation of the Ice Age shells, animal bones, faeces of Tasmanian devils and glass Aboriginal tools. “We were personae non grata at conferences for years,” he says. “There was a degree of sympathy among our colleagues at the difficulties we faced in our research, but other colleagues basically said we had it coming. Their view was that whatever Indigenous communities said, was what went.”

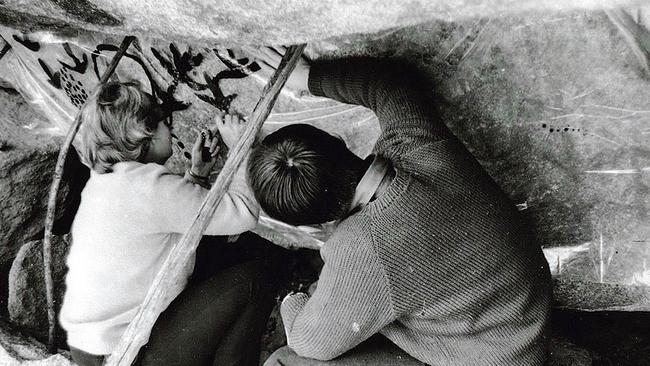

The profession built since the 1960s by people like the renowned John Mulvaney – the “father of archaeology” in Australia – was being transformed around archaeologists like Murray and project leader Professor Jim Allen. Unlike the Indiana Jones-style excavators of earlier days, the La Trobe team had followed the rules, working under permits granted by the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service. They believed they had the support of the Aboriginal community. Indeed Rocky Sainty, at that stage chair of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Land Council, had been a consultant on site, there to ensure the protection of any human remains that might be unearthed in the caves.

It was an exciting period in Tasmanian archaeology. Plans to flood Pleistocene era caves, including the famous Kutikina cave, as part of the Franklin dam project had focused attention on the prehistoric treasures in the area. Kutikina had only been discovered in 1977 by a geomorphology student, Kevin Kiernan, while rafting down the Franklin River. He named it Fraser Cave after the then prime minister in an attempt to draw attention to it, and it was saved thanks to the 1983 High Court ruling that the federal government had the power to block the dam.

The “no dams” protests of the 1980s had been led by environmentalists, but the controversy drew world attention to a state where archaeologist Rhys Jones had been working since the 1960s. Tasmania, where colonial powers had murdered or driven out Aboriginal people in the 19th century, was now the place to dig. It was also the place where Indigenous Australians were reasserting their rights over their past.

By the early 1990s, the La Trobe team had transported material from several caves back to Melbourne. Their permits had expired but the scientists did not bother to apply for permission to continue analysing the relics. By the time Jim Allen asked for an extension in 1994, Indigenous rights were undergoing a revolution: the previous year, the federal parliament had passed the Native Title Act, and Aboriginal Australia was finding its voice.

Karen Brown recalls it as a time when Indigenous people began to be more assertive. “We were totally fed up,” she says. “Archaeologists were coming into Tasmania and undertaking excavations, and when they found material, instead of giving it back to the community they took it away with them.” Adds Rocky Sainty: “We thought, ‘Well, if we can make this stop, it’s never going to happen in Tasmania [again]. We will never let another archaeologist at a university come in here for a PhD or a thesis. It’s just not going to happen anymore’.”

The Tasmanian Aboriginal Land Council took its repatriation request to the state government, and the permits were refused. Months of negotiations followed as the scientists argued they were 85 per cent through their analysis and should be allowed to finish before returning the material. There were suggestions the work could continue in Hobart, not Melbourne, but this was not pursued, and La Trobe kept the material.

Once, science might have won, but the Council took the archaeologists to court. A week after the decision the material was taken to the Museum of Victoria, and later a Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service truck with two Indigenous employees on board took possession of the relics. Back in Hobart, they were eventually placed in a Council building. Once again, La Trobe was told analysis could continue there.

As the nation’s archaeologists gathered themselves for a world where research would depend increasingly on Indigenous permission, Tim Murray decided to stop working in Tasmania, and Jim Allen decided working in Hobart was impossible. Looking back, Murray says there was never a question that the material would not be returned; some had already been sent back to Hobart. “[But] it was not possible for the analysis to be completed in Tasmania as our staff, labs and other equipment were all based in Melbourne,” he says. “We did not have the funds to re-establish all of this in Hobart.”

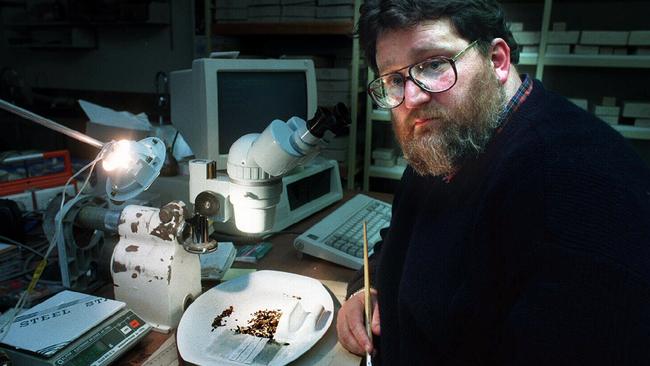

One of the team, Richard Cosgrove, was devastated. “We thought we were doing the right thing. We were researchers, and we were archaeologists,” he says. “We argued that there was no point digging up this material after being given the permits, because to not do the research would mean that digging it up had just been vandalism. We weren’t into the politics, and it became obvious that archaeology had become very political.”

Thirty years on, the full story of the Tasmanian Affair can be told. It’s a story of how, in the end, both sides found a way through the impasse. And it’s a story with implications today, as Australia seeks a balance between Indigenous rights and economic development. Last month, federal environment minister Tanya Plibersek’s veto of a tailings dam for a proposed gold mine near the western NSW town of Blayney, on Indigenous heritage grounds, divided opinion in the town and across the country.

A clash between development and heritage is not unusual, and Blayney is very different from the La Trobe case. But at its core are many of the same questions asked back then: who owns the past, who should control access to that past, and how much of the past should be preserved? In short, how far should governments go in restricting the rights of landholders – Indigenous and non-Indigenous?

Archaeologists should not have been surprised when Tasmanian Aboriginal people asserted their rights over the cave material in 1994. For more than a decade, academics had confronted the ethical and moral issues about who should call the shots in digging up the past. In an address to a Hobart conference in 1982, Indigenous archaeologist Ros Langford had delivered a stinging critique of contemporary archaeological practice. Her paper to the Australian Archaeological Association was titled Our Heritage – Your Playground. It positioned her white colleagues as players in the colonial project who carelessly exploited First Nations people in the name of science, and their careers.

“From our point of view,” Langford said, “we say – you have come as invaders, you have tried to destroy our culture, you have built your fortunes upon the lands and bodies of our people, and now [you] want a share in picking out the bones of what you regard as a dead past. We say it is our past, our culture and heritage, and forms part of our present life. As such it is ours to share on our terms.”

The speech hit home. The Association immediately passed a resolution that archaeologists must “obtain permission from the Aboriginal owners prior to any research or excavation of Aboriginal sites”. Jim Allen commented that some archaeologists feared Indigenous people would exclude those “whose reconstructed ‘pasts’ do not agree with their own”, but Langford’s speech resonated with another leading archaeologist, Isabel McBryde, who was already involving Aboriginal communities in fieldwork in NSW.

If John Mulvaney was the father of the profession, Isabel McBryde – who is now 90 – was its mother. As a woman in what was then a male-dominated profession, she never achieved the public profile of people like Rhys Jones, whose crash-through reputation made him a darling of the media in the 1980s and 1990s. But as early as the 1970s, her commitment to working with Indigenous communities to discover the questions they had about their past set her apart from colleagues who came with their own set of predetermined questions.

In 1983, a year after Langford’s speech, McBryde organised a symposium in Canberra titled Who Owns the Past? It was a chance for the discipline to debate how to dig in a land still occupied by the direct descendants of those whose past was being excavated in the name of science. It was, they were beginning to recognise, nothing like doing archaeology in Egypt, or Syria, or Italy. Archaeologist Sharon Sullivan told the symposium that Aboriginal ownership was “very difficult to dispute” in moral and cultural terms. She added that “whoever controls research into such sites controls, to some extent, the Aboriginal past”. Sullivan noted that laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s had been framed by archaeologists to protect “relics” rather than their meaning to Indigenous Australians. Aboriginal monuments were ignored while Australians, keen on their colonial history, argued that 200-year-old buildings should be granted the status of the “palaces, castles and manor houses of Europe”.

When Indigenous culture was examined, it was too often through a white – “scientific” – lens, according to critics like Koori historian and land rights campaigner Wayne Atkinson. In 1985, he wrote: “These are Aboriginal sites, not archaeological sites.”

Arguably the most important archaeological find in Australia was the discovery in 1968 of skeletal remains of a woman who lived 42,000 years ago at the Willandra Lakes in the far west of NSW. “Mungo Lady” was gathered into a suitcase and taken to the Australian National University where her discoverer, Jim Bowler, worked. As early as 1973, the work was questioned by Aboriginal people but the zeitgeist was all about the science.

Researcher Wilfred Shawcross said that in the 1970s, he and other archaeologists “had not remotely considered that the Aboriginal people would be concerned about what we were doing … I suppose we felt rather righteous – I felt rather righteous – that here we were rediscovering their past. Shouldn’t they be grateful?”

It would be 1992 before Mungo Lady was repatriated; Mungo Man, discovered by Bowler in 1974, remained at the ANU until his remains were returned in 2017. In 2022, their remains were reburied after years of controversy.

Distinguished Professor Sean Ulm of James Cook University rejects the argument that the remains should not have been reburied because they may be needed for further research – the same argument made 30 years ago by La Trobe scientists who worried the Tasmanian artefacts would be reburied. Ulm says: “Looking at it pragmatically, those ancestral remains were held in a suitcase for decades, and not just a couple of decades, but for 50 years. They were studied to death … You can go online and find digital scans of those ancestral remains.”

He says the researchers had a responsibility for how things ended: “They had ample opportunity to study these remains, they had ample opportunity to engage with those communities and have a different discussion from the one that emerged.”

After his clash with the Federal Court, Tim Murray turned most of hisfocus to post-1788 archaeology in Sydney and Melbourne. Now an emeritus professor, he is writing a book on archaeology in Australia for Cambridge University Press and reflecting on the chances of his field surviving as an academic discipline when an estimated 95 per cent of archaeological work is done by commercial consultants. Murray was among the second generation of archaeologists trained by those who, led by John Mulvaney, recognised prehistory did not begin and end in Egypt, and that Australia held incredible information about the past. It was a heady era as carbon dating revealed the story of human occupation here.

By the mid-1970s, archaeologists had shown Indigenous Australians had lived here for at least 40,000 years. Science elevated Indigenous culture in the minds of white Australians who had dismissed it as nomadic and unsophisticated. Suddenly old equalled important, and scientists rushed to discover the next big piece of the past. The proof of age provided by archaeologists would eventually play a key role in the political power of Indigenous Australians, even as they fought back against the “cowboy” archaeologists.

Murray is 69 now, and laments what he sees as a shift from global to mostly local concerns in archaeology here. In his eyes, there is a divide between pure research carried out to advance knowledge, and archaeology for cultural heritage management and preservation. “There are some Indigenous communities who say, ‘We’re not interested in the global histories of humanity, we just want to find out what has happened to us’,” he says. “That’s fair enough, but that shouldn’t be the only question being asked.”

Murray is referring to the fact that now, the majority of archaeologists work as private consultants, mostly on Indigenous heritage. They are partners in a complex dance of cultural conservation and monetisation of land involving Indigenous owners, miners and developers, and state and federal bureaucrats. Rather than researching broad scientific questions, the consultant’s job is usually to examine specific sites – the proposed Blayney gold mine, for instance – ahead of development. The bulk of archaeological work is carried out by private consultants for heritage or development. The number of archaeologists in Australia has almost doubled in the past 20 years, but only about 20 per cent work in academia. One reason why so many go private is funding: this year, the Australian Research Council granted $13.5 million to 12 projects. As well, obtaining permission from traditional owners can be drawn out and involves building agreements, often with different groups.

There’s another layer to the question of who controls the past, too: the complex web of state and federal legislation, which can often add to delays and mistakes. One of the worst examples of the failure of heritage laws was the 2020 destruction by Rio Tinto of the Juukan Gorge site in the Pilbara.

There had been two consultants’ reports – in 2008 and 2014 – verifying the significance of an area where human occupation dated back 46,000 years. But Rio Tinto was given permission by the state government to proceed under a 50-year-old heritage law that did not give traditional owners a veto, and in effect gagged them from speaking out. The global outcry proved a disaster for Rio and a new law was passed last year in an effort to modernise the legislation. But after resistance from landholders, the laws were scrapped in August – a month after they came into effect – with a return to the 1972 law but with no gag and a right to review.

Michael Mansell, one of Tasmania’s best known Indigenous leaders, says that 30 years on from La Trobe there are still big gaps in legislation protecting the ability of Aboriginal people to control work on their past. “If you’re going to change the way things are done, you’ve got to legislate – and Aboriginal heritage legislation, both federal and state, is in a very poor state,” he says. “It leaves an enormous scope for the bureaucrats and archaeologists to exploit the poor legislation to their benefit, at the expense of the Aboriginal communities.”

It seems that “pure” research is easier in Sri Lanka or Africa than in Arnhem Land; of the 12 Australian Research Council grants in 2024, five are for fieldwork in Australia, five are for offshore fieldwork, and two are for projects in Australian laboratories where modelling, rather than empirical research, is the order of the day.

Tim Murray says the focus on specific projects for developers, miners or land councils has turned archaeologists away from the “really significant discoveries” of earlier years. “There’s a sense in which the great pioneering phase of doing archaeology in this country has come to an end,” he says. “Of course important work in the archaeology of Indigenous Australia continues to be done … as it should be, but it is also the case that the significance of Australian history to our understanding of the history of global humanity should also be a focus of research and discussion.”

On the upside, the shift to consulting archaeology has seen Indigenous people play a bigger role in the sector – not so much as archaeologists, because only 2-3 per cent of archaeologists are Indigenous, but as monitors and in related jobs on land councils and heritage groups. It’s a growth area for Indigenous employment, with generally higher wages in the private sector compared with those earned on university research projects. But the skew to private investigation has created another problem for archaeology – a massive pool of “grey literature”. Sometimes it is unavailable because it is commercial-in-confidence; but often it is not circulated widely simply because consultants don’t have the resources to do so.

Dr Billy Griffiths, whose 2018 book Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia tracked the development of archaeology in Australia, agrees grey literature is an issue for the public record. “There’s valuable, amazing science we don’t learn about, and even neighbouring groups don’t learn about, because of who funds the arrangements,” he says. “So much work is being done by consulting archaeologists who don’t have the time or the money to write up that research for a broad audience.”

Adelaide archaeologist Keryn Walshe, the former principal researcher at the South Australian Museum who has worked for decades researching the renowned Koonalda Cave on the Nullarbor Plain, says that since the 1990s “a massive imbalance has come about between what is added publicly to the record of Indigenous archaeology and the amount of archaeological work undertaken” because of the skew to consulting.

“To me that is extraordinarily problematic,” she adds. “Very few outcomes from the archaeological work done in Australia are now made public, because most of it is driven by development applications.

“The fundamental difference was that 30 years ago all archaeology was geared for knowledge production. Now, the vast majority is geared towards getting private corporations and government sectors over the line with heritage legislation so that a development can go ahead – or not. This has changed the very way that archaeology is undertaken across the country. It is clearance work, not research-based activity.”

Richard Cosgrove, now an adjunct professor at La Trobe, worries that much consulting work is “research without any questions”.

“I know colleagues who have just sat there counting bones and stones, and who say, ‘OK, well, there’s a hundred of these and 50 of those’,” he says. “You go, ‘Well, what’s the significance?’ This stuff just languishes and takes up space in museums. Many archaeological labs are full of material that is dug up and, in many cases, devoid of any questions that should drive the research.”

Thirty years ago, archaeology in Australia was dominated by academics whose careers depended on access to First Nations material. Not surprisingly, the La Trobe case was a talking point for decades. Over the years some wondered what became of the artefacts returned to Hobart: had they been reburied or were they gathering dust in a basement? The assumption was they had been lost to science.

Tim Murray lost track of what happened, but Richard Cosgrove did not. The Tasmanian Aboriginal Land Council had made it clear that scientists could work on the stored material in Hobart, but that was deemed financially impossible by La Trobe. Cosgrove never gave up, though. “He was basically the only archaeologist at the time to come to talk to us and say he wanted to do further investigation,” says Colin Hughes, now a consultant Aboriginal heritage officer, who was closely involved in the case. “Cosgrove always involved the Aboriginal people.”

It paid off, and in 2004, Cosgrove began research on the material. Over almost a decade his team catalogued more than a million pieces, including more than 100,000 pieces of stone tools, looking at seasonal variation in hunting patterns and the lithic (stone) industries of the Ice Age.

It’s a big number, but Cosgrove says the excavations were small: “This material is a fantastic window into the past and the behaviour of Ice Age people and how they managed to thrive and survive through those times. The only other comparable archaeological material with that sort of richness comes from the famous French Late Pleistocene site in France.”

In 2015, the cultural materials were moved to an Aboriginal centre at Risdon Cove on the Derwent River. By then Cosgrove had completed his project, with the data widely available. The experience was important to him professionally, but it taught him a much bigger lesson: that “negotiated research” is the only option.

“If you go into a community with a project, you need to understand it is not always the most important thing for that community,” he says. “You might say to the community, ‘Here are the outcomes for the community and for science. And this is a question that’s really interesting. Are you interested?’ They might go, ‘No, bugger off’. It’s not the most important thing for them; they are dealing with health, the law, substance abuse, family violence, all this sort of other stuff. It’s not just a simple matter of Aboriginal people seeming to say ‘No, no, no’. It’s deeper than that.”

Rocky Sainty, who now works as an Indigenous consultant in Tasmania, sums up the mixed feelings many have about the value of science. “We don’t need an archaeologist or an anthropologist to tell us our history, or what we ate 200 years ago or 1000 years ago,” he says. “That’s all passed down in stories from our old fellows. There’s no issue with archaeologists working with Aboriginal people on country and studying plants and different aspects of the country, but there’s no need whatsoever to be doing excavation to find out what we ate 200 years ago. We know that.”

What about the idea that the rest of the world needs to know the story? “Bugger the rest of the world,” says Sainty. “I mean, how much do you want to know?”

His position is not universally held, but underscores the dilemma in researching a living culture.

Says Dr Billy Griffiths: “Collaborative research is key. Scientific knowledge is constructed by the questions we ask. And if the questions are being asked by Western scientists, or if the questions are being asked by Indigenous knowledge holders, the answers are going to be very different. Increasingly we’re seeing new questions being asked that lead to radically different insights.

“That’s what Isabel McBryde was calling for all those decades ago – it’s a process about how you learn and understand the knowledge and interpret the information as much as it is about the number of studies or the oldest dates. Part of the challenge is to recognise that it’s not just what we learn, but how we learn it.”

Sean Ulm, director of the Centre of Excellence for Indigenous and Environmental Histories and Futures funded by the Australian Research Council, is clear on control. “I thought this question was settled 30 years ago,” he says. “These days best practice First Nations archaeological research in Australia is fully co-designed between researchers and traditional owner communities, and often the research agenda is set by the aspirations of the Indigenous owners.

“I do hear some of my more senior colleagues being nostalgic for a past that doesn’t exist anymore. When I was an undergraduate student in the late 1980s, at the University of Queensland, it was only a few years after people had been doing routine archaeological excavations without any involvement or consultation with traditional owners.”

Tim Murray agrees the Tasmanian affair was the “ground zero” of this new world of collaboration: “When the work began in Tasmania, discussion of such matters was still in its infancy, as were the roles of state and federal managers in the granting of research permits and the evaluation of the work being carried out.”

The one million fragments from the La Trobe excavation are a fraction of the material examined by archaeologists since the days of John Mulvaney. But 30 years on, the Tasmanian affair remains a pivotal point in the debate about how science, economics and heritage interact in a nation where Indigenous Australians have a 65,000-year link to the land.

Looking back, Richard Cosgrove is keen to reshape the debate about who owns the past. “Ownership comes down to the things – the stone tools or the pottery,” he says. “But this is a debate about what the past looks like. I don’t think anybody can own that. They can own the material, they can’t own ideas.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout