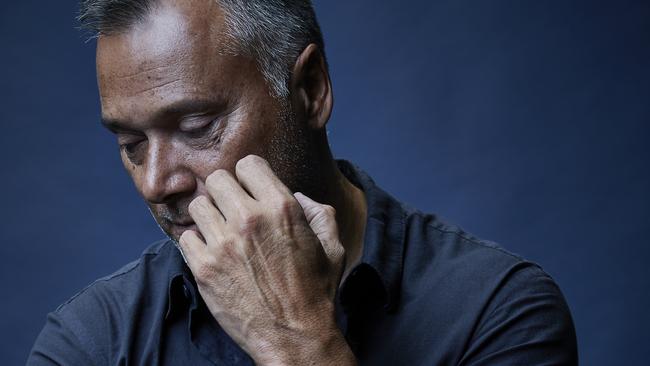

Stan Grant on his soul-searching journey following Queen Elizabeth II’s death, Q+A, ABC response

Journalist Stan Grant embarked on a soul-searching journey into his Indigenous past and his faith following the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

Let me tell you about my pa, Keith. He was the man who loved my grandmother, Ivy. If we knew nothing else about him but that, it would be enough. In loving Ivy, he defined himself. He was the black man in a tent by the river who whistled at the pretty blonde girl as she walked by. He made room for her in his tent and made a place for her in his heart. He was a Kamilaroi man, a short, stout man who laughed easily, sometimes drank too much, read old western novels, loved a bet on the horses and loved me. In my childhood I was closer to him than anyone else.

My grandfather lived with us on and off. I would sit for hours with him, sometimes saying nothing, just feeling him close. We sat together listening to the radio each Saturday morning as horseracing commentators ran through the form guide. My grandfather had his newspaper out and would mark his selections for the day. I would go with him as he put on his bets, then we would cheer his horses on and he would strike his leg with the rolled-up paper like a horse whip as he rode his winners home.

We would wait on the steps for the postman to come each pension day. If the mail was late, Pa would send me off to find the postman. I would run up and down the streets to fetch that pension cheque, because I knew what a day we would have. We had our own little ritual. Pa would cash his cheque and take me to the cafe for an ice cream with nuts and chocolate sauce in a glass bowl. Then he’d give me some money for my mother and head off to the pub. I would stay awake waiting for him to come home. I would hear him singing in the distance, then crashing into the side of our house. I would go out and help him in. Sometimes he’d scatter money over the ground and I would scoop it up and keep it. Days later, when he was skint, I would give it back to him. I took care of him and he took care of me.

My Uncle Kevin wrote about tragedy. About the time his little brother Neville died. He was only 10 months old. All they had to bury him in was a little box. My uncle wrote how he and his sisters picked wildflowers and put them in the box with little Neville’s white booties, and buried him in the ground next to the tin humpy they lived in. My uncle wrote about the time police came to that same block of land. They came to force Pa and his family to leave. A developer had bought it and the blacks would be moved on. My uncle said the kids all ran away, his mother – my grandmother Ivy – was crying and Pa stood his ground. The police officer put his gun to my grandfather’s head and my uncle said his father slumped to his knees. Then the bulldozer rolled over the home my grandfather had built. Uncle Kevin tells this story better than I could. Looking back, “It was like we were part of that house too, and it was trying to help us somehow. But that big blade was too strong and the wire snapped and let go. Then our house came tumbling down and lay motionless in the dust. It was all over in a few seconds.”

The White Queen is dead. My grandparents’ love defied a country and it defied an idea – an idea of whiteness. Was my grandmother white? To those white police, she wasn’t. She wasn’t white to the black man she loved, the black children she brought into the world or the black people who opened their arms to her. My grandmother was no longer white to white people, and that’s why they broke her. They broke her by treating her as black. Or maybe something worse; she was someone who chose to be black. Love made her black … for a while. Just a while.

The life Ivy shared with my grandfather couldn’t last. She left and married another man. She told my mother that she was out of her mind. She said she had a breakdown, and when she came to her senses she was with a man she did not love, and far from her children and the little tin humpy and her Keith. With her white skin, ruby lips and curly blonde hair, my grandmother, to those who passed by her, was now just another old white lady. She was no longer a threat. No longer a scandal. No more did the police stop her in the street. She was welcome at the hospitals that had turned her away when she was having her child. She was back, and the lie of whiteness could again become her lie. Yes, I suppose this is the truth: that as much as she was my blood, my grandmother was ultimately white. Even if there remained a part of her that did not belong to white Australia, white Australia belonged to her. She could possess it. And that’s what whiteness is, after all: it is possession. Possession of land, possession of souls.

The White Queen is dead. The ABC is nervous. It has circled around these topics all week. The republic. Colonisation. Empire. Genocide. Racism. If they’ve been discussed, it has been in muted tones. No one wanting to step outside the lines. At one point it is suggested to me that Q+A might not discuss the Queen’s death at all. One producer suggests we do a program on aged care. That would be ridiculous. No. We will do it, I say, and I will put Black voices front and centre. And Black women. My friend Sisonke Msimang – the South African writer – and the Wiradjuri lawyer Teela Reid agree to be part of the program.

At times like this, my role is impossible. As journalists, we cling to our objectivity. But that is a lie. Who is objective? What a bloodless idea. There is nothing objective about the way my people – my family – have been treated. And what is objective about this ritual mourning of the White Queen? I am expected to ask the questions. To give the guests “equal time”. To make sure all voices are heard. As if truth can be divided and weighed. At other times I can step back, try to be neutral.

Tonight I find my anger rising. The White politician [we have invited onto the show for balance] talks about “ugly scenes” in our history. That’s right. Invading someone else’s country, importing disease, shooting defenceless people, cutting off heads, dismembering bodies. These are “ugly scenes”. This man in front of me says: “Were there skirmishes? Were there massacres? Yes. Were they perpetrated by the Crown? No. They were perpetrated by individuals who disregarded the letters patent...” As he speaks, I can feel the veins tightening in my temple. There were wars fought on our soil. Soldiers under the Crown were dispatched to kill us. Vigilante groups were formed to round us up. To force us over cliffs. To set fire to our homes. To lace our food with poison. I can feel my heart pounding. Sisonke and Teela answer back at him. At the time, everyone in this colony knew it was a war. The newspaper called the battle for Bathurst – as it was known – an exterminating war. Every face in front of me disappears, and I am seeing my father, my mother, cousins, uncles and aunties. Whiteness is not White people. I have to keep reminding myself of that. It is an organising principle. It is a way of ordering the world. It is an invention. An idea. A curse. But this night there are White people on the panel who are appalled. They challenge the White politician. But I am sorely tested now. I feel wounded. I feel empty. I just want to go home.

-

“As journalists, we cling to our objectivity. But that is a lie. Who is objective? What a bloodless idea.”

-

The night after, I am lying on my bed. My heart is racing. I am struggling for breath. I really feel like I am dying. Who rescues me? My people. I can feel them with me. I can feel my grandfather next to me. I can hear my father speaking our language. My mother’s words are ringing out across time. From a time when she was young. When she wore her brother’s cast-off socks to see the White Queen. When she lived in a tin humpy with a White mother and a Black father. When broken biscuits made her cry. I can feel them, and I write. It is their voices that speak to me. It is their words that fall onto the page. It is their voices that matter.

How do we find peace in a place where we still cannot truly speak to each other? Some say we are a nation of parts: Indigenous heritage, British foundation, filled out by the cultural richness and renewal of migration. In the sum of those parts, it is said, we can find something new. It sounds good. People like to hear this. But it sounds convenient, like a compromise. It sounds like politics to me. It is a beautiful idea of Australia but we haven’t earned it. Anyway it is the wrong way around. We are part of a place. We are waters and rocks and trees and earth and birds and animals and languages that grew out of this place. What good a republic? What good a thing called Australia? That’s who we are. We have to bring meaning to that. Before a republic, we have to know what it means to be here. We have to know first where we are.

I am a Christian and I find no home in whiteChristendom. The faith I was raised in – that beautiful Wiradjuri harmony carried on the voices of a people forsaken – found a place with God in spite of everything Christendom had brought. Ours was the crucified Christ; crucified as a political act. Our theology is political. It is a theology of liberation. And it is black. My uncle who preached in black churches across NSW always said he was a Wiradjuri Christian. He said he did not follow a failed European Christianity. How could he? It is unfashionable to talk about Christ and God and faith. But religion matters to me. I could not find the love to stare into the face of history without hate if I did not have God. If I did not carry with me always and forever the voices of that little white wooden mission church.

The White Queen is dead. I go for a run. I love that turn from day to dusk, and I follow the path from my parents’ home back along the river and up into the town. Then I hear a sound. Voices. People singing. And I recognise the melody. I stop and look across at a stone church. There, in a circle, are a handful of people. They strum guitars and together their voices seem to blend into one. “O Come, All Ye Faithful” – I love that hymn. There, in that moment, it is even more beautiful. They are not in church but outside it. They are under a tree. And they are singing for the sheer joy of it all. It takes me back to the little white church on the mission. Back to when I was a boy. But these people are not Wiradjuri. They are white. Does that matter? Yes, it does. There is a history between us. There is still a divide that can feel like a chasm. There are so many ways I would not understand them, nor they me. We come to God in our own way. We read the same scriptures but they speak to us differently. I have been in white churches and I have always felt slightly out of place. Not unwelcome, not at all, but as if I am a day out.

My faith tells me God put me here right at that moment because I needed to hear them. To others it may just be coincidence. Perhaps at another time I may have just passed by. But this is the journey I have been on. Since the death of the White Queen I have wrestled with anger, resentment, betrayal, sadness and return; return home and to find a place of love and peace. My faith has been deepened and strengthened by the ordeal. In truth I have been on this journey all my life. All those little towns. Those questions without answers. The peace I find by a river or listening to my people speak our language or hearing a hymn is a peace that eludes our country still. There is too much suffering, too much pain; too little justice. But there is always love. Love that keeps my people alive. Ngiyang. Mayinyi. Language. People.

Edited extract from The Queen is Dead by Stan Grant (HarperCollins, $34.99), on sale May 3.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout