Diversity vs unity: Crosby’s warning on Muslim vote

Sir Lynton Crosby shaped conservative politics at home and abroad for decades. As Anthony Albanese’s cabinet colleagues face serious challenges from Muslim vote candidates, what is his advice?

For a private figure, Sir Lynton Crosby has been called many things in public. Political guru and puppet master. Evil genius and master of the dark arts. Dog-whistler and wielder of wedge politics. Fleet Street’s newspapers, with a sneer, a hint of respect, and their usual flair, have dubbed him “The Wizard of Oz” (The Times) and “The Lizard of Oz” (The Guardian).

“The Outback Rasputin is my favourite,” Crosby tells The Weekend Australian Magazine during a rare sit-down interview at his property in the NSW Southern Highlands. As a global political strategist and founder of CT Group, which has grown from a Liberal Party offshoot to an international consulting business with offices in Washington, the Middle East and throughout Europe, he’s now permanently based in the UK (although naturally he still has plenty to say about Australia’s political climate). It’s a pivotal moment for CT Group, whose 21-year marriage to the Australian Liberals ended in divorce last year, while Crosby stepped down as chief executive and into the role of executive chairman. We’ve been invited to the sprawling country pile where he usually returns for the summer to discuss the next chapter in his extraordinary career.

This is hobby farm and horse country. Homesteads sit at the end of long gravel driveways bordered by manicured gardens. Down the road is Nicole Kidman’s family fortress and the surrounding acreages are studded with the weekend retreats of political royalty and high society. The Crosby residence is peaceful and spacious. Inside his study the decor is low-key elegant and hung with gentle oil landscapes. The most striking feature, though, is the floor-to-ceiling bookshelf. Gaze along it and the great men and women of conservative politics peer down from the shelves: Churchill, Thatcher, Reagan, Menzies.

And like stag heads mounted on the wall are the leaders Crosby helped shape into political juggernauts: John Howard, David Cameron, Boris Johnson. These are the men he built vote-winning machines around, in part shaping Australia and Britain along the way.

Crosby’s critics say he won those elections by tapping into the electorate’s fears, whether it be the arrival of boat people (Howard vs Beazley, 2001), Scottish nationalists (Cameron vs Miliband, 2015) or socialists on spending sprees (Johnson vs Corbyn, 2019). They would add that his style isn’t suited to modern politics. But fans cite Crosby’s calm under fire and laser-like focus to “the message”, and say that leaders today would be “crazy” not to listen to him.

Speak to the man himself and he’ll tell you that for all the chatter about “dark arts”, it’s the Menzian values he grew up with that have been his north star. He believed – and still does – these principles to be the salvation of Australia and the West. “The success of countries like Australia has been built upon a recognition of certain sorts of values: reward for effort, personal responsibility, mutual obligation to use a John Howard phrase, freedom of speech and freedom generally,” he says. “The case for those values is not often made these days – not by politicians, let alone others in the community.

“And I think that that worries me more than anything else … if a society doesn’t have the anchor of those beliefs, it sort of darts here and darts there based on the latest noise, the latest trend, the latest issue.”

So why, then, is Lynton Crosby shunning politics?

CT Group, which Crosby set up with pollster Mark Textor in 2002, parted ways with the Australian Liberals late last year. While neither side says CT’s backing of the Voice to Parliament campaign (spiritually driven by Textor and at odds with Peter Dutton’s position) was the cause of the rift, it didn’t help. Amid the fallout, the firm that had delivered thundering election wins for centre-right parties in Australia and overseas said it was shifting out of the business in which it had built its reputation: polling and research for politicians, the smallest but highest-profile part of the CT Group.

The strategy, explains Crosby, is to focus on corporate work. It’s vastly more lucrative and less public-facing. There’s less name-calling in it. And a market has opened up. Businesses like Qantas, Woolworths, BP and multinational business leaders, he tells me, in fear of woke activists and in love with progressive causes, have needed reminding that values hidden but still intrinsic in Western society are their future. They need Lynton Crosby.

Of course, Crosby is also keen to remind us that, at age 68, he is not retiring any time soon. The Outback Rasputin is still at the top of his game. “Rupert Murdoch’s got 25 years on me, so I’ve still got 25 years to go. I’m not going to go off and do other things.”

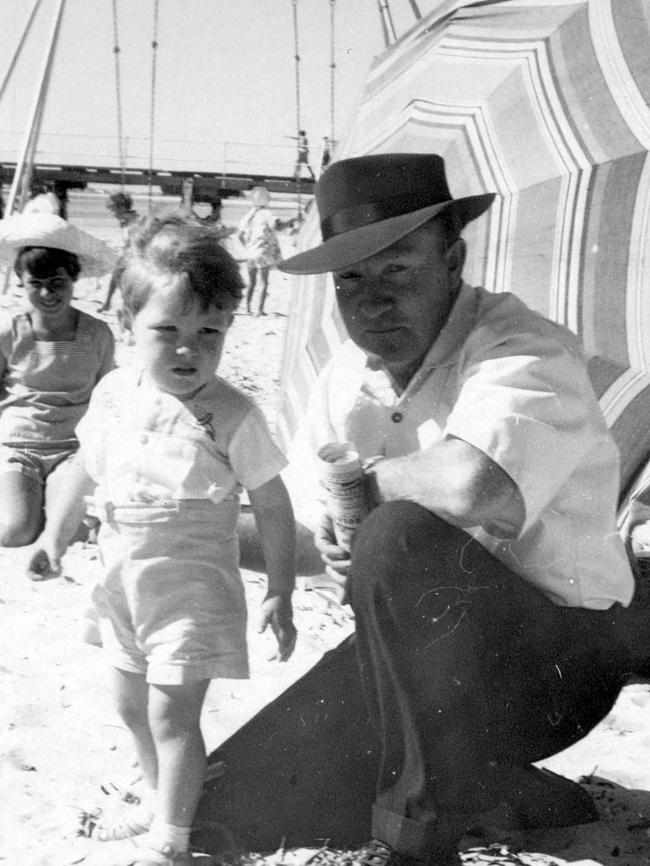

Lynton Keith Crosby was born in Kadina, South Australia, the largest town on the Yorke Peninsula. His father Keith and mum Sheila were cereal farmers. Keith also owned an arts-and-crafts and music shop where Crosby worked as a kid. It was, Crosby says, a happy childhood. After studying economics at the University of Adelaide, where he was president of the Liberal club, politics beckoned. He did all the party’s rubbish jobs – he was a South Australian Liberal operative in the ’70s and ’80s when Labor was the only show in town. During that era he had his own ill-fated tilt at the 1982 South Australian election. Crosby was targeting the seat of Norwood and the centrepiece of that campaign was … a leaflet. “I cringe whenever I see that leaflet,” he says. It was one of those one-size-fits-all campaign pamphlets that essentially misread the electorate. We said, ‘Oh, we’ve got to put out a leaflet, we’re going to put out a brochure’,” he recalls. “We didn’t sit and take the time to understand, OK, who are we trying to get to vote for us?”

Crosby has quipped that he made “a marginal seat into a safe Labor seat” – proof that he spares himself none of his trademark withering criticism. It was the first and last time he underestimated the importance of careful messaging in a campaign. And he never ran for political office again.

That withering criticism is on full display when, midway through our photoshoot in his Southern Highlands manor, I tell Crosby that Biden has gotten to his feet at the Democratic National Convention.

“Let’s turn it on,” he says eagerly.

He switches the channel (an MP waffling in Australian parliament’s question time) to bring into view the ancient US President. “From one incoherent person to another.”

With his eyes glued to the screen, that little wry grin comes out. “Kamala’s not smiling, is she?” he says as Biden rambles on.

Could Crosby have saved Biden’s candidacy, I ask? “The climate was there for him to win, except for one dominant and very significant factor, and that is competence,” he says.

How would Lynton Crosby run a campaign for Donald Trump? Crosby says he’d tell him to stay on the message, and focus on the things American voters care about.

But his close friend Jim Messina – Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign manager and former White House official, who met Crosby when they worked on David Cameron’s 2015 campaign – scoffs at the idea of a Crosby and Trump partnership. “I don’t think Lynton would last one day before he told Trump to f..k himself,” Messina says. “His politics probably fit in pretty well with Trump, but what Lynton abhors more than anything is political incompetence and political inability to stick to the message.”

And yet a fortnight out from the election Crosby suspects Trump will win – an “educated guess,” he says. “It’s unpredictable.”

Boris Johnson once spilled the beans on a Crosby dark art, the so-called “Dead cat on the table” strategy – that is, a dramatic announcement to distract voters from the campaign’s problems. Crosby muses that Trump may have taken the dead cat advice a little too seriously in his debate against Harris. “Trump has more issues to exploit, if only he’d focused on them rather than eating cats and dogs.” Then he quips: “The issue of eating a dead cat really is a ‘dead cat strategy’.”

With four election victories in a row for Australia’s centre-right party under his belt, Crosby first moved to the UK to work on the Tories’ push against Tony Blair in 2005. His strategies didn’t work for their leader Michael Howard. Some blamed the bluntness of Crosby’s anti-immigration messaging, but the party brand was still too damaged from the Thatcher-Major years. Regardless, George Osborne and David Cameron, the future Chancellor of the Exchequer and Prime Minister respectively, who worked on the campaign, were impressed. In 2008, with the Tories still in Opposition, Cameron now as party leader and Osborne as his number two convinced Boris Johnson to run for Mayor of London. They knew this popular but chaotic former editor of The Spectator needed a hard bastard to keep him on track. Enter Crosby.

In his new memoir, Unleashed, Johnson writes that no one thought he could win against London’s long-time hard-left mayor Ken Livingstone in 2008. “Watching from Australia was Lynton Crosby, the political strategist who propelled John Howard to several election victories. He turned to his wife Dawn and said: ‘This man will never be Mayor of London,” Johnson writes.

A true story, says Crosby. Well, mostly.

“I wasn’t in Australia. We were actually in a short-term rental flat on Park Lane in London when we saw Boris’s shemozzle of a press event on the news. That’s when I turned to Dawn...”

Johnson goes on to write that Crosby had one mission: to make him focus. And he did – Johnson comfortably won the 2008 mayoral election for the Tories.

Throughout Johnson’s mayoral campaigns and Cameron’s uphill yet victorious battle in the 2015 general election, Crosby’s profile grew. And he wasn’t afraid to ruffle feathers. Osborne tells The Weekend Australian Magazine: “I remember a meeting of all the Conservative MPs and candidates we had … where he said something like: ‘I don’t know what your names are, I’m sure you’re all important people, but I don’t think you are particularly. Here’s the strategy’. He was ruthless.”

Messina puts it a little less smoothly than Osborne. “He kicked the shit out of them,” he says. The kicking worked. In 2015 the Tories won their first majority in 23 years and Crosby got a knighthood the following New Year for “political service”.

Messina, who has worked with some of the toughest men in US politics – he’s literally won the Machiavelli Award – says nobody on a campaign has any doubt Crosby is in control. “I was walking into the Margaret Thatcher stateroom, a strange place for a Democrat, and he just laid everything out … he put his ego aside, it was a big deal I was doing this,” Messina recalls. “But it was clear he was in charge.”

Even the wayward Johnson fell into line and, after winning two mayoral elections in Labour-leaning London, with Crosby’s advice rose to the office of Prime Minister. “[Johnson] certainly had an ability to connect with people, which is rarely seen … I’ve never seen it before to the same extent,” Crosby says.

Other advisers pushed into Johnson’s orbit and Downing St was soon beset by scandals (notably, its mid-lockdown staff parties). Crosby was once again called upon for wise counsel in 2022, but it was too late. Johnson stepped down as an MP in June 2023.

Could the Tories have avoided their catastrophic defeat to Keir Starmer’s Labour in July if they’d stuck with Johnson?

Arguably they would have kept some seats, Crosby says, but he’s not so sure they’d have held onto power: “There’s no doubt Boris was one of – not the only, but one of the contributors to his own demise because of some of the staff he employed and because he didn’t put in place a proper system to deliver … he was good at communicating but he didn’t have the mechanisms around him to guarantee policy implementation. [Although] he did on big issues like the Ukraine war and the vaccine roll-out,” Crosby says. “David Cameron called him the greased piglet, like he could get out of every situation … but ultimately, if your people feel that you have failed to deliver or you have been distracted from their concerns, they’ll get you.”

Some years earlier Crosby had been drafted at the last minute to advise Theresa May, who turned out to be one of the worst campaigners in British political history. Her supporters turned on Crosby when she lost the party’s parliamentary majority in that election.

Does it annoy him? The Wizard of Oz label? The idea that he’s pulling all the strings and that whenever anything goes awry for the Tories, he’s to blame? Crosby suggests there’s some colonial pomposity in British attitudes towards him. “There’s still a class structure … it’s endemic, and it’s in people’s minds,” he says. “It’s hard, and partly because you don’t have it in Australia, you sort of don’t know when you’re doing something you shouldn’t,” he adds.

“I’ve never had an issue telling anybody at any level what I thought about anything, of course … [but] sometimes you have to temper it … sometimes they think you’re a bit of an oddity, but you can use that to your advantage. ‘Oh, he’s the Australian’.”

Crosby and CT Group were not involved in the most recent UK election, in July. “Thank goodness,” the Wizard says with a heartier laugh than usual. How do the Conservatives bounce back from that defeat? Crosby has some ideas. They can start off by not calling themselves “Tories”. The term is toxic.

“I’d reprise some version of Menzies’ forgotten people,” he says. “The people who get up in the morning – I used to say this to Boris, and Boris agreed – I catch the bus at half past five, six o’clock, right? You see the tradesman with his tools on the bus at six o’clock going to work. It’s not fair that their taxes are being taken to reward somebody who’s not getting out, not taking responsibility for bettering their lives, not taking responsibility for their kids, who want everything for nothing. So I think I’d focus on reward for effort, aspiration, personal responsibility, national unity … I would focus on those five or six values.”

It’s 1996 – Howard vs Keating – and Crosby’s first federal election as campaign director for the Liberals. He packs his family up and drives them down the east coast to Canberra for the contest that would change his life.

Mark Textor, who met Crosby in the early 1990s when he was the Queensland Liberal state director, remembers the Crosbys pulling up outside his place. “He decided to drive to Canberra from Queensland because he’s a thrifty bastard, right?” Textor says. “He’d asked me if I could pick up the keys to his rental place. So I’m standing outside my front garden with the keys, and then I saw this little blue [Holden] Barina … these things are f..king tiny. The entire Crosby family is absolutely crammed into this small car … all these faces pressed against the glass, with all this other stuff in this tiny car, as he grabbed his keys to start his life in Canberra.

“That said everything about Lynton’s commitment … Here he was to win the next federal election, with a battered old Barina driven down from Queensland. That’s just bloody marvellous.”

I tell Crosby that I’ve heard him and Textor described as brothers. “Little brother,” he responds. “He’s doing lots of things. He’s motivated by community issues and other things, and cycling, which I hate.” But Textor, he adds, “has been at the core of what we’ve developed” even if as non-executive director he is no longer “day to day active” at the firm.

The 1996 result was, of course, a landslide win and the end of the Keating era. Crosby would become federal director of the Liberals in 1997, replacing Andrew Robb, and be at Howard’s side for the GST fight of 1998, the Tampa affair in 2001, and the contest against Mark Latham in 2004.

“He didn’t drop his bundle. Advisors sometimes drop their bundles quite heavily. He never did that,” Howard recalls. “In the time he was federal director, gee, we went through a lot of difficulties and he was always calm.”

A year before the 1996 federal election Crosby had weathered Kate Carnell’s tumultuous campaign in the ACT, where savage infighting among Liberal candidates almost sunk the ship. Carnell says: “He could have strangled [the candidates] … I wanted to do much worse to them.” But she won. The last Liberal Chief Minister to govern in the ACT praises Crosby’s dogmatic devotion to message and discipline. “He was incredibly clear about where we were headed and what we were doing … he never shouted.”

During the late-1990s debate over an Australian republic, Crosby and Textor gave Howard rare (at the time) polls showing Australians were going to vote to keep the British monarchy. The pair had figured out there was a disconnect between publicly expressed sentiment and how people would vote in the secrecy of the booths.

Says Howard: “I’m not saying it’s a sign of, in itself, a genius, but it was just an example of how professional and technically accurate they could be”.

So how does all this translate into Crosby’s new corporate focus? Put another way, what place does a Menzian values crusade have among monuments to capitalism? A great theatre lover, Crosby tells of an exercise he did to show how the great stages of London were suffering under the rise of activism.

“BP were providing subsidies so young people could go and observe the Royal Shakespeare performances … a hue and cry appeared to have developed on social media opposing the fact that an oil company was sponsoring something against what young people supported,” he says. “Several community groups, or groups with, you know, community-group-sounding names all came out … and in the end, the Royal Shakespeare Company and BP decided to part ways. It didn’t smell right to me so we did an exercise on it.”

Papers appear in his hand. Crosby always has a paper or a data set to show. “You find out the same people were fronting these different groups, right? There they are … there they are meeting. There’s a house they lived in together, yeah?” he says. “It’s a bit like when I was a kid and I used to watch Rin Tin Tin … there’s a sergeant and a trumpeting bugler over the hill and they tie bushes to the back of the horses, they blow the bugle, they race around, create a lot of dust and make it look like there’s a cavalry on the other side of the hill so they can scare off the people attacking the wagon train.

“And that’s activism.”

Crosby thinks businesses should stand up for their worth in society – the jobs they create, the money they make.

Are cautious CEOs ready for that? The back of Crosby’s business card quotes the 6th-century BC philosopher Solon’s old saying, “When giving advice, seek to help not to please.”

Textor says Crosby jokes that it’s “their excuse to be rude to people”. But he also says Crosby is bringing to the business world an iron-clad commitment to capitalist values and something else many other corporate strategists lack: a sense of responsibility. “What people admire about Lynton is they know he won’t run away from it after,” Textor says.

Crosby first of all warns business leaders that they cannot play the activists’ game. “There’s been a tendency, I think, for often it’s PR advice [to say], ‘Oh, we’re being attacked, shut it down’ rather than sometimes stand your ground and make your case,”Crosby says.

“Everything is political. And business leaders are operating in a political climate. There’s no doubt about that. One thing they need to remember, though, is that X or Twitter or whatever you want to call it, and lots of emails and a lot of noise often does not reflect the view of their customers.”

He reaches for an example close to home – the fallen Woolworths chief executive Brad Banducci, who scrubbed Australia Day from his stores and found he had no political capital left when faced with claims of price-gouging. “By not having Australian flags and other Australia Day material available, he was depriving them of their opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty to Australia. So it’s this sort of sense that he was pursuing his issues rather than understanding his audience’s issues and concerns.

“Some business leaders think that by promoting these [progressive] activities, they will be thanked by the community, whereas what we found in that very same research was if they simply focused on the fact that they create jobs, they create wealth ... that’s a much more compelling argument.”

Eyebrows were raised when CT Group became a pollster for the failed Voice to Parliament campaign but Crosby says: “Maybe some people who are critical about us in relation to the Voice misunderstand who we are and what we do as a company … we’re not two people who just work for the Liberal Party”.

Besides, he adds, “we came to be involved in it before the Liberal Party had determined its position. Well before the Voice was ever talked about, we had done quite a bit of work on reconciliation, because even people who voted no in the Voice referendum … subsequent polls showed overwhelmingly they believe that as a community we need to come together, black and white, whatever race, and that the problems need addressing”.

Crosby speaks about the Voice’s failure analytically. “The Voice referendum, and the referendum for whether we remain a constitutional monarchy, were two examples of the voters … essentially saying, ‘Given everything we’ve got going on right now, why are we doing this now? It’s not relevant to me, and I don’t know what I’m voting for’,” he says.

Would he have voted yes? Crosby responds that he is a UK resident and is not on the Australian electoral roll.

I push him again – if he lived in Australia, would he have backed the Voice?

“I would have because we worked on it.”

It’s noticeable, as you walk through the door of Crosby’s country house, that there are no pictures of prime ministers and kings. It’s the faces of his wife Dawn, his daughters Emma and Tara, and the little ones that shine out of family photos. Crosby visits Australia several times a year to be here for his grandkids’ birthdays. He has also secured Adelaide Crows membership for all four grandkids. There’s early voter targeting for you.

Looking out at the sunshine and the rolling fields on his heavenly Southern Highlands farm, Crosby says: “One thing you realise when you go abroad is how good Australia is. It is a great country and we’ve got a lot of things going for us, and we mustn’t lose sight of that.” But he certainly has worries about the country where he honed his craft.

Just as several Muslim independents knocked off UK Labour MPs in the July election on the back of anti-Israel sentiment, Anthony Albanese’s cabinet colleagues are facing serious challenges from Muslim vote candidates. “If you’re Tony Burke, and you’re looking at the makeup of your constituency or your electorate, you know, you’re thinking twice,” says Crosby. He warns against the movement towards segmenting voters – like the Muslim vote is doing. “The word diversity is used a lot and the word unity is not used often enough … everything’s being chopped and diced, and that I think can be ultimately quite destructive.”

His solution for leaders? Shared values. Put another way, it’s the search for common ground.

“You can be a Muslim tradesman, a Jewish tradesman or a Christian tradesman, or an agnostic tradesman. But if I communicate with you on the basis that you work hard, you take responsibility for your life and you take responsibility for your family, and you put into the community, and that contribution to the community should be acknowledged – you can all relate to that.”

Right-wing and upfront, Peter Dutton feels like a Lynton Crosby style of candidate. The Opposition Leader has succeeded in keeping his party united, and understands his voters, Crosby says. “People will know what they’re going to get, and that can be very compelling.”

Could Dutton kick Albanese out of the Lodge after just one term? “I think it’s very hard for Anthony Albanese to have anything other than a minority government,” Crosby says. “But it’s also possible there could be a Liberal minority government, too, or some sort of semi coalition of independent candidates and the Liberals and Nationals together.”

Dutton makes clear his respect for Crosby in a statement to The Weekend Australian Magazine. “I have known and admired Sir Lynton for over 20 years,” he says. “His work with John Howard is legendary and to his credit he has created an incredible global business.”

And yet Sir Lynton will not be whispering in Dutton’s ear.

Some Liberals are highly critical of CT Group’s research and record in recent years, with the 2022 election loss under Scott Morrison a particular sore point. “For all that investment, CT’s record was really 50/50 in the past decade,” one party operative says. “The technology was tired, the wedge issue strategy was tired.”

Nonetheless, Conservative bulwarks Morrison and Tony Abbott were present at CT Group’s 21st birthday bash in Sydney weeks after the Voice referendum. And John Howard is still picking Crosby’s brain for political wisdom.

“I mean, given his track record, people would be crazy not to use him,” Howard says. “I don’t have direct influence on those decisions … but I still talk to everybody … I think he’s got to [be listened to] because he’s been there, done it.”

Says Crosby: “We’re not as price competitive as we once were for that sort of [Opposition polling] work”.

Bottom line: “We’re a different business than ... (a) campaign, political business”.

The firm is now moving in more lucrative directions, with a corporate intelligence arm and a push into the security industry, hiring defence heavy-hitters like former British army chief Sir Mark Carleton-Smith. Most of the time, it’s under the radar work but not without scrutiny. Its founder’s profile means that even small-time courtroom dramas hit the headlines as “Lynton Crosby’s consultancy”.

Ultimately, Crosby Textor has outgrown its Liberal party origins and its ambitions lie elsewhere. “The company’s growth has mirrored my experience,” he says. “We started here [in Australia], we went to the UK, we built the UK into our biggest business – we can go into Africa, the Middle East...”

Interestingly, the most prized possessions in Crosby’s NSW getaway aren’t anything to do with politics. They are mementos from his friendship with the comic genius Barry Humphries. When I remark on his bookshelf, he skips over the politicians’ memoirs and with glee produces a signed copy of Humphries’ memoir. He also shows off a painting that the creator of Dame Edna Everage and Sir Les Patterson made on the banks of the Seine in Paris – a present from Humphries.

A decade or two after that great generation of expat Australians – Humphries, Rupert Murdoch, Clive James, Robert Hughes and Germaine Greer – made their mark on Britain, challenging English snobbery, Crosby has followed suit. Does he ever wonder what life would have been like if he had won that seat in Adelaide? Could he have been more than the man behind a curtain? A premier … or more?

“Who knows?” he says. “You think about it … I admire people who are prepared to get their name on a ballot paper. You’ve just got to make a go of whatever you have a crack at.”

It doesn’t get more Aussie values than that.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout