Sculptor Peter Schipperheyn’s monumental battle over William Barak statue

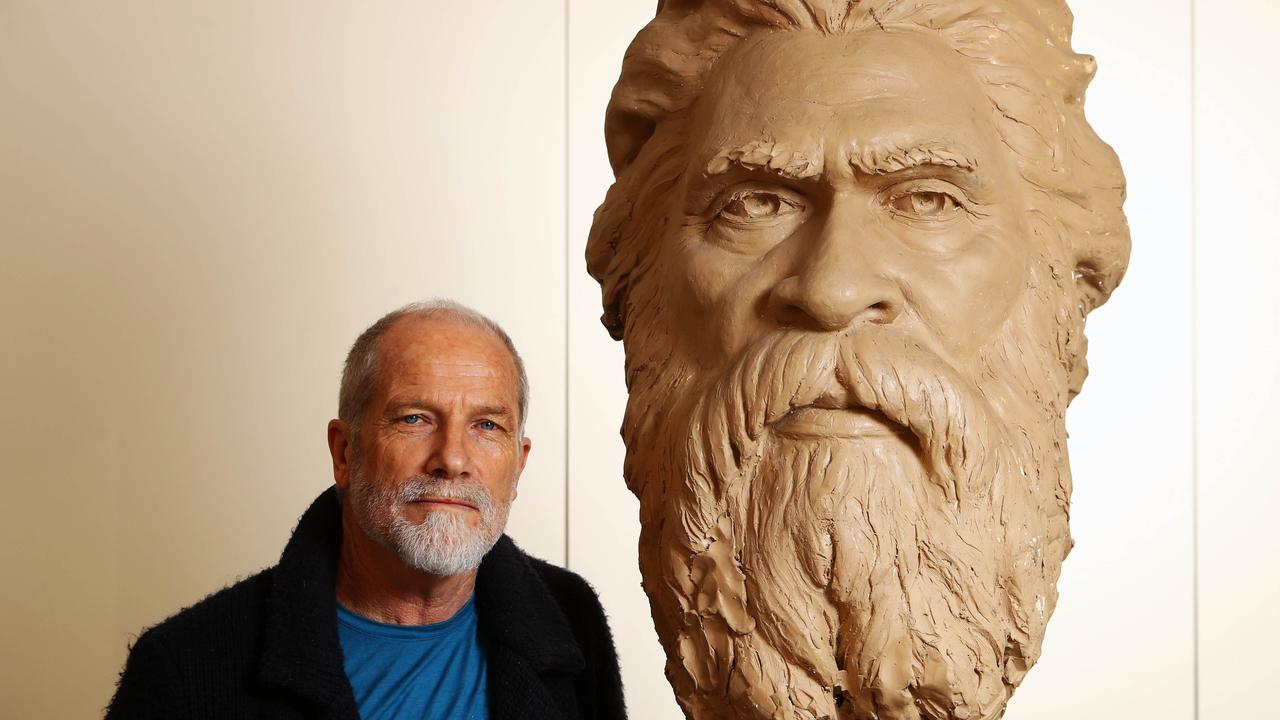

While monuments around the world topple, Peter Schipperheyn’s colossal sculpture of indigenous leader William Barak remains stuck in the studio.

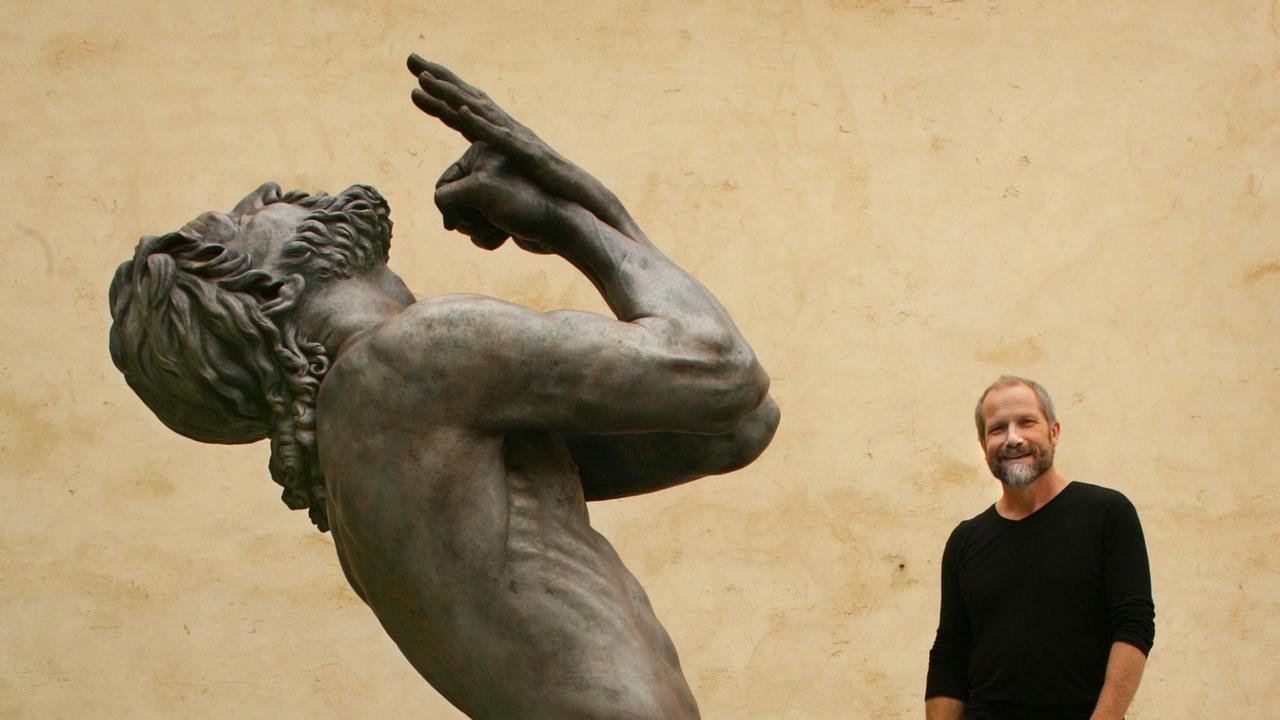

Think of him as an alchemist, a finely tuned artisan who can adroitly convert ordinary into extraordinary. Beauty may be an essential element of the business to which Peter Schipperheyn has devoted his adult life, an ageless craft that involves considerably more physical toil than you might normally associate with the arts. But there’s a magical element to his work that makes it especially enchanting, his ability to take something vast, whittle it down to a fraction of the original, and end up with something significantly greater.

Thirty years ago, in one of many examples, he took a 12-tonne block of Carrara marble – his preferred material, from the same quarry that Michelangelo favoured – and began knocking it into shape. Months later, he had reduced it to four tonnes, and in the process created an oversized rendition of a naked woman delicately shielding her eyes, Paura del Intimita (Fear of Intimacy).

In the world of sculpture, Schipperheyn is a master, expertly recreating the human figure in marble and bronze. In the world of Australian sculpture, he is a masterful rarity: a talent who has been able to make a living from it. “No other living Australian artist has so totally dedicated himself to seeking a truly contemporary expression of Western arts’ most inspired tradition,” the late Edmund Capon, long-time director of the Art Gallery of NSW, once said of the man and his craft.

Now Schipperheyn is hoping to embark on the final stage of his most significant project. After years of working in a classical style heavily influenced by Europe, he wanted to create something that was culturally relevant to Australia, “like an Australian [version of Michelangelo’s] David”. It’s a massive work, in space and time, a 4.2m-high monument that has become his passion. And even with the abundance of patience he has amassed over decades of painstakingly chiselling human forms out of marble, he could not have imagined it would take more than 20 years to realise. There’s just one problem. He estimates he’ll need $1m to see it through.

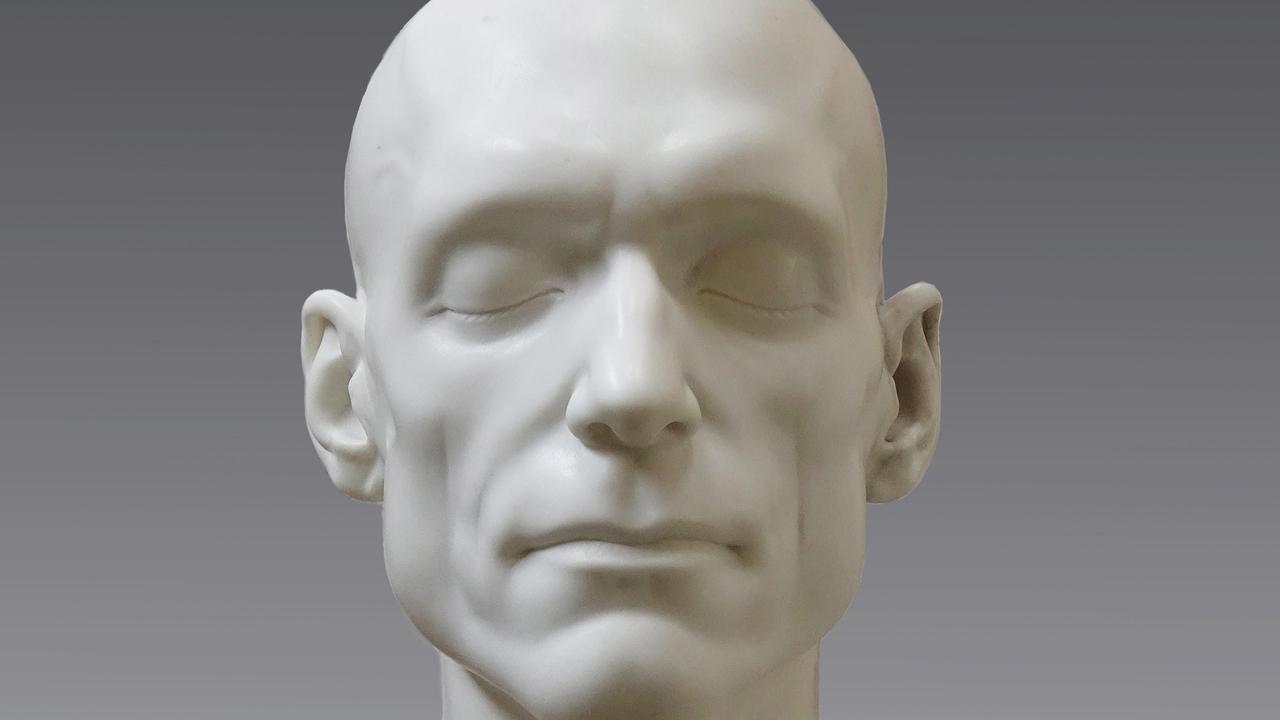

Pick a face and see what Schipperheyn can dowith it. Dame Joan Sutherland? All profile but mostly ear, Schipperheryn’s unique tribute to the acclaimed Australian soprano graces the Sydney Town Hall. Musician and former politician Peter Garrett? Schipperheyn’s rendition is a 200kg carved marble bust, eyes closed, and housed at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. Nobel laureate Patrick White is a striking bronze bust on a marble base. And former prime minister Paul Keating is a work in progress; he exists as two intricate models in Schipperheyn’s Melbourne studio, a very personal project that he hopes will have widespread recognition. “I am carving it for the nation,” he says as he stands in the lofty space, surrounded by lifelike plasticine figures and a well used kit of tools, and proudly presents his intricate impressions of his friend and supporter.

A former PM as patron? Schipperheyn may not be a household name, yet his list of benefactors spans the worlds of politics, media (columnist Phillip Adams), sport (polo player Sinclair Hill) and even espionage: the late Laurie Matheson, a key witness at the 1983 Royal Commission on Australia’s Security and Intelligence Agencies, was a patron and when he died Schipperheyn was commissioned to create a sensuous gravestone featuring a life-size figure of a naked woman sleeping. (Although it bears his name, Matheson is actually buried in the next grave.)

For a man whose life’s work has been largely devoted to the human form, it is not surprising that Schipperheyn’s circles are so varied. As he says: “Your sense of what you can do is profoundly affected by the people you meet.” It’s a sentiment that can apply not just to the way he has been nurtured as an adult artist, but how he was dissuaded from pursuing his passion as a child.

Growing up in Melbourne, Schipperheyn was instinctively drawn to the arts. As a boy he loved painting and drawing as much as soccer. He also played classical guitar, and at 15, because his Dutch-born father refused to buy him one, he built his own electric model. When official art classes ended after his second year of high school, his parents sent him to private lessons. Still, he was mostly dissuaded from believing that his talent could somehow also be his future. “I was being told at school and by all the elders in my life that art at best could be a hobby; there was no way you could make money as an artist, so don’t even bother,” he says. “I remember thinking, ‘This is what I like to do and this is what I think I am good at.’ But it seemed like there was no way I could make a living out of it.”

No one, however, had factored in his tenacity. By the time he finished school, passion had triumphed over pragmatism and he enrolled in a graphic design course at Swinburne Institute of Technology. After six months he was called in by a lecturer over his surrealistic interpretation of an advertisement for a swimming pool, complete with bones at the bottom of the water. “And the lecturer said, ‘This is a beautiful drawing. It’s well done… but you’re not cut out for commercial arts.’ ” Switching to fine arts and design at Caulfield Institute of Technology, he met fellow student Cinzia Ruffilli, who was studying sculpture. “I saw Cinzi the first day I enrolled. I looked across and she had the most beautiful profile: incredible ears, and a sensuality. And it was her Italian-ness.”

While their relationship flourished – they have been together for 44 years – after a year Schipperheyn found that this course was not for him, either. “I thought it was a waste of time. I wanted to have instruction in the classic world, the world of good drawing… You must develop a facility for drawing because once you do that you can do anything.”

In his early 20s he headed to Rome, a city of sculptures, and talked his way into the Accademia di Belle Arti to study painting. After nine months, and homesick, he returned to Melbourne and Ruffilli and continued painting, with regular visits to the National Gallery of Victoria to inspect some of his favourite works. There, he would walk past a sculpture by Jean-Robert Ipoustéguy, Death of the Father, and soon it and the idea of sculpting as a vocation captured his attention. “The extravagance of it just began to enter into me,” Schipperheyn says fervently. A youthful-looking 65, he is a warm and expansive storyteller. “I began to see it as an option for myself. I am a physical guy. I like working hard.”

With no formal training, he began sculpting from timber and fibreglass and eventually marble. He moved back to Italy in the late ’70s on a scholarship and on weekends worked in a commercial studio surrounded by international artists reproducing classical works. “From the first week in Carrara I loved being there. What opened up for me was an incredible experience of the whole European tradition of sculpture.”

The physical toil of shaping marble, he discovered, also suited him. “As a painter I found it hard to stay in front of the canvas basically stationary for hours at a time. Whereas when you’re carving there’s a physical release.” And there was something about the marble itself, the “feedback from the stone, from the sound, the feel, the hardness of the grain… it’s like a living thing, it’s telling you things all the time. The sound of it when you’re carving: when you get a dull thud you know that’s not good. When it rings like a bell you know that you’re not pushing the stone to any limit.”

He won his first sculpture prize in 1978 for Senility, a giant hand with a walking stick, and commissions followed, from schools to religious organisations and a growing array of private art collectors. By the time he was awarded the Wynne Prize in 1992, for a pair of huge white masks that philanthropist Ken Myers immediately gifted to the Art Gallery of NSW, he was already deeply contemplating his next move.

Until the late 1990s, William Barak was unknown to Peter Schipperheyn. By then in his 40s, his search for an Australian David had spanned a decade. “It became clear to me that I should make a monumental sculpture that drew on Aboriginal heritage.” Over many years he had decided on an oversized statue of an indigenous male, much like an image he had seen in a school history book as a child. “If I want to put this into the realm of something iconic, it has to be of a size that creates an importance,” he says of the towering figure he envisaged. “If you make him life-size he’s only got the same importance of you and me.”

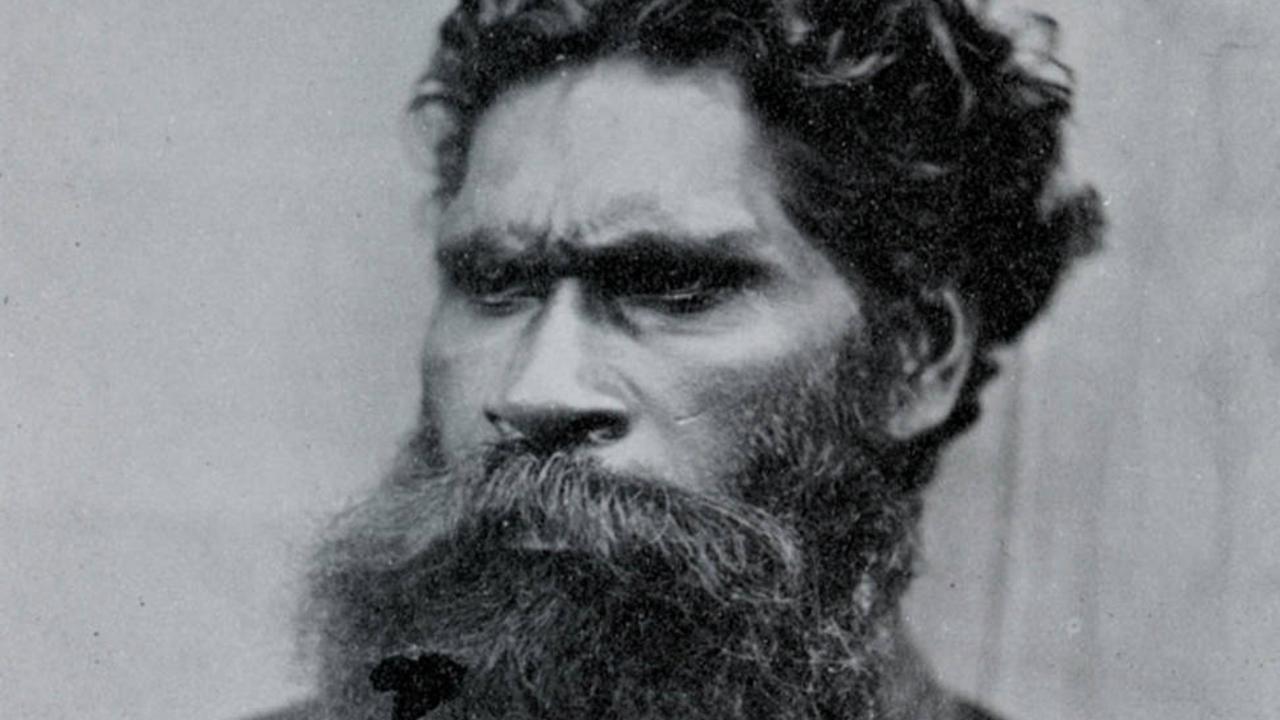

The breakthrough was when Ruffilli came across an old photo of Barak wearing a possum skin cloak. “I came home and I said, ‘Peter, you have to do this man’, ” she says. Spurred by his wife’s enthusiasm, he finally had his subject.

Born in 1823, William Barak was an activist, artist and cultural ambassador and was known as the last leader of the Wurundjeri clan. As a boy he saw his father, a Wurundjeri elder, sign John Batman’s treaty transferring the Port Phillip area to Batman himself. With a limited education, he joined the native police at 19 and became a respected tracker at a time when Victoria’s indigenous population was plummeting.

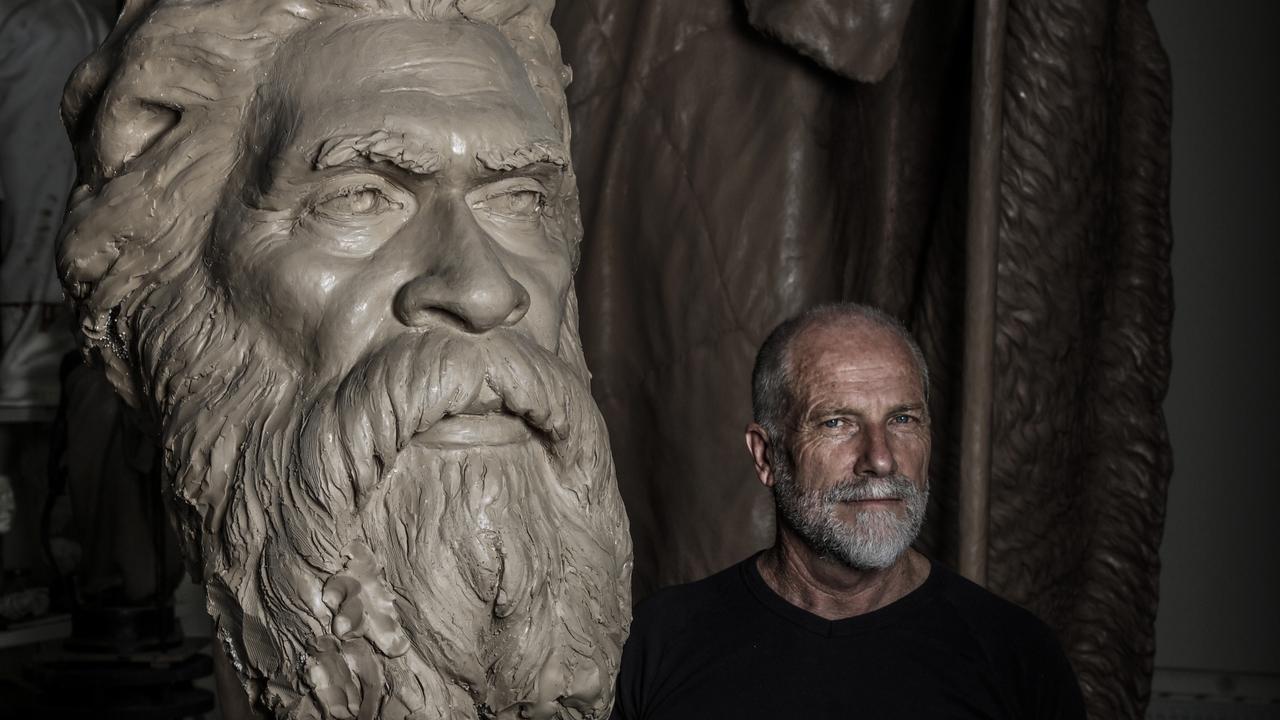

As the leader of a decimated group, Barak set up a small self-sufficient farming community near Healesville, and found himself having to prove to white Australia that indigenous Australians could survive on even the smallest piece of land. As clan leader, the wise and dignified elder led multiple negotiations and long walks to parliament in Melbourne to plead the case for his community. But by 1893, the government had taken over half of the community’s land before it was ultimately closed. Barak died in 1903. “It’s a story of suffering,” Schipperheyn says as he stands in his studio beside his 4.2m-tall sculpture of a regal-looking Barak, whose likeness was approved by Wurundjeri elders in March 2017. Built on a steel frame, with a layer of foam overlaid with plasticine up to 10cm thick, it took him eight months to create. “It is like a lifetime’s work,” he says proudly.

While Barak’s story remains relatively unknown to wider Australia, his reputation has grown in his home town. In 2005, a bridge named in his honour was opened near the MCG. A decade later, the facade of a high-rise apartment block was unveiled at the former Carlton and United Breweries site on Swanston Street, with Barak’s portrait, based on a drawing by Schipperheyn, fashioned into the full height of the block’s southern face.

The Aboriginal activist denied citizenship in his own country was now a part of his city’s skyline, although not everyone was pleased with the result. “The problem I have is not with the idea that Barak should have a place in the consciousness of the city, but with the overt association between the 530 luxury apartments that are the Portrait building’s actual purpose, and the lifelong dedication of William Barak and the entire Kulin nation to the struggle over land,” historian Christine Hansen wrote in The Conversation. “To place high-end CBD real estate and an image of the most famous of 19th-century land rights activists in the same frame is a cruel juxtaposition [that] exposes our blindness not just to history but to its contemporary consequences in institutionalised racism and unequal power relations.”

Still, interest in Barak grew. Grocon, the company behind the Portrait building, funded Schipperheyn to begin work on his sculpture. He travelled to Italy to work on the model, intending to have it cast in bronze there, but various delays meant that after many months and an exceptionally hot Italian summer, the clay model began to dry out until it was eventually unsalvageable. Schipperheyn returned to Australia and spent more months creating a second mammoth model, this time out of plasticine. But eventually time and funding ran out. “I finished the sculpture and there was no more money to cast it in bronze.”

After all this time, he is tantalisingly close to an end. But finding that final million or so to bronze his work and install it near the William Barak Bridge is tricky. Grocon is no longer involved in the project, the national economy is crippled by a pandemic, thousands have suddenly found themselves out of work, and the Black Lives Matter movement has seen statues of controversial historical figures toppled globally – a trend that leaves Schipperheyn deeply conflicted. “Every statue and every artwork is of its time,” he says. “Yes, culture shifts, but I don’t think that warrants tearing down things… I see it from an artistic point of view. There’s a language of art which to me is separate from politics.”

In the meantime, his own creation awaits its final move. “I am now getting concerned,” says Schipperheyn. “It can’t sit there in the studio indefinitely, otherwise this one risks decaying in some form or another.” He has been in contact with possible backers, including the Victorian government, but still with no definite outcome. For now, his masterwork remains at its point of creation, inside his studio, ready for whatever happens next. When it finally leaves here one day, it will leave an enormous void, but it will also provide a sense of achievement. “There’s nothing that exists to commemorate William Barak,” he says. “It’s waiting to go. I see every reason why it should be standing proudly in Melbourne.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout