René Redzepi, Tom Kerridge and Heston Blumenthal on leaving the kitchen

One of the world’s top restaurants is closing, its head chef burnt out. And he’s not the only one closing the door and moving on.

There was a telling moment during my conversation with the Noma head chef René Redzepi at the end of last year. It came when I asked about his legendary 80-hour working weeks at the three-Michelin-starred Copenhagen restaurant voted “best in the world” five times in the 20 years since it opened, and where Redzepi was touted as the most innovative chef on the planet.

“It’s hard for me to have a day where I’m not working,” he shrugged, glancing up at the Noma “test kitchen” (a sort of glass Portakabin) from where he was speaking to me via Zoom in the midst of what appeared to be a storm. “Mondays are what I call a half day – I might come in at 11am and leave at 5pm. And then on Sundays, there might be two or three hours of work. I also leave early once a week, between 6pm and 7pm.” Early? That’s not early, I countered. “It’s very early to me!” he exclaimed. “Early enough to actually have dinner with my family anyway.”

In a world altered by Covid, in which working from home, flexible hours and a desire to swing the pendulum back from working hard to hardly working are all in vogue, Redzepi’s lifestyle – one that means he struggles to spend quality time with his wife, Nadine, and three daughters, Arwen, 14, Genta, 11, and Ro, seven – seemed horribly out of sorts.

Perhaps he secretly felt the same way. Last month, the 45-year-old chef announced that Noma will close at the end of next year. Instead it will become “Noma 3.0”, a series of travelling pop-ups and a test kitchen/laboratory. “We have to rethink the industry. This is simply too hard, and we have to work in a different way. It’s unsustainable,” Redzepi said. “Financially and emotionally, as an employer and as a human being, it just doesn’t work.”

“A human being”: those three simple words reveal so much about what’s been going on behind the scenes. Redzepi didn’t reference the subject of burnout directly in his announcement, but he did when we spoke a few weeks ago. “It’s something I feel regularly,” he told me. “Slowly but surely you try to understand what it is that drives you there. Why do you suddenly feel like you have nothing to give? That you’re just empty of ideas, of words, even emotions sometimes, you know?”

Those who truly know are Redzepi’s fellow chefs, many of whom have recently unburdened themselves about the toll that work has taken on their lives. Like him, they have admitted the role their tempers played in creating toxic kitchen environments – Redzepi has called himself a “beast” and “bully” and with an air of regret told me that the years he spent shouting and screaming at staff were the “worst of my life”. Among his cohort of famous chefs there have been admissions of broken marriages, addiction, exhaustion and workaholism, culminating in a re-evaluation of priorities.

The image of the high-stakes commercial kitchen, with a stressed head chef, is hardly new, of course. But until recently it has been seen as the cross every tormented culinary genius must bear. Now it is emerging as a dysfunctional, extreme lifestyle that’s a race to the bottom in pursuit of prizes. Indeed, in a 2017 survey of London’s professional chefs by Unite, 51 per cent said they were suffering from depression due to overwork, 27 per cent were drinking to get through a shift and 56 per cent were taking painkillers.

Andrew Clarke, former head chef at the acclaimed restaurant Brunswick House in London, now runs the mental health charity Pilot Light, aimed at hospitality professionals. In 2016 he posted on Instagram that he had been “suffering from a pain so extreme that I could barely cope … I hated who I was and wanted to kill myself every time I came home from work”, later adding that he’d been working 100 hours a week amid a cheffing culture that sends the message “if it doesn’t hurt, it’s not yours”.

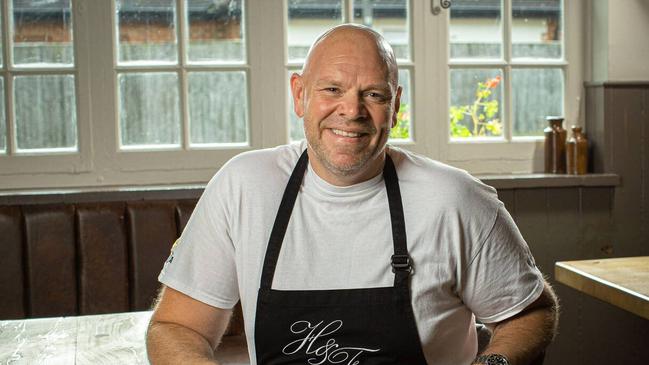

Substance abuse is an open secret. There’s no suggestion that Redzepi relies on anything more than the Danish rye bread and homegrown lemon balm tea he consumed throughout our conversation. But others have put their hands up. Tom Kerridge no longer drinks, after years of alcohol abuse each night after service. Phil Howard, former chef-owner of the Square in London’s Mayfair, has spoken about how he graduated from cocaine to smoking crack while running his kitchen, working 16-hour days, six days a week, for 15 years.

“That’s the chef’s biggest psychological struggle – spending so much time working that there isn’t enough time to achieve all a human being needs to achieve to be happy and content,” he said in a 2016 interview. And after coming clean about the extent of his addiction, he found that other chefs were getting in touch with similar tales.

-

“It is so much pressure, you guys have no idea”

-

Adam Hardiman, former chef-owner of Madame Pigg in east London, told The Times last year, shortly after leaving rehab, that he had been “a functioning drug addict” working 18-hour days. In one of his first jobs, the young chef had been presented with a chart by a member of the kitchen team and told to write down “your name and how many lines you do”. Hardiman was convinced that the head chef in the acclaimed 2021 film Boiling Point was based on him, so realistic was the portrayal of an alcohol- and drug-addicted head chef running an explosive kitchen. The truth is more likely to be that he’s the rule, not the exception.

There may, of course, be many reasons behind Noma’s demise. The pandemic, for instance, which forced those diners who can afford to pay $700 a head for dinner to stay at home and Michelin-starred restaurants to produce economical takeaway food – Noma became a burger joint, for which Copenhageners queued around the block. Or the fact that the restaurant started paying its interns in October, after pushback from a new generation of young chefs unafraid to call out their employers, which added an estimated $50,000 to Redzepi’s monthly outgoings.

Also age, perhaps. Redzepi was 25 when he took the helm at Noma 20 years ago. As Phil Howard put it: “You’ve gone from young and invincible to no longer being in the driving seat. You wake up thinking, ‘How? When? Where?’”

Yet even in the face of burnout, it seems that the top chefs struggle to put to one side their obsessive natures.

Heston Blumenthal’s desire to improve his mental health after moving to France took on the same perfectionist qualities as his life in the kitchen (he has also recently been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD). “Over the period of a year, I drank no wine. I meditated for about 10 minutes. I brushed my teeth and gums mindfully. I paid attention to how my gut felt, I’d hang from the door frame to stretch my spine. I’d write a gratitude book, then I’d read a page of a Zen book, then I would take my mountain bike out for an hour, then I’d go to the gym for an hour, then I’d work between 10.30am and 7pm. I’d stop for a 40-minute meditation in the afternoon. I’d drink Athletic Greens, I’d have an apple, maybe do a 15km run, come home, have dinner. At one point, I was running 80km through the vineyards … I exhaust myself. And then I stop and think, ‘Maybe that’s the problem.’”

In the wake of his own recovery, Howard ran more than 25 marathons and did 25 triathlons. Redzepi has already been on something of a journey of self-discovery, having “many, many, many hours of therapy”, meditating daily and developing an obsession with hiking – walking the long-distance Camino de Santiago twice, the Shikoku 88 in Japan twice and the Caucasus mountains of Georgia, as well as all over Scandinavia as part of what he described to me as his “longevity plan”.

“It is so much pressure, you guys have no idea,” he added, shaking his head of floppy hair. We may not have listened before, but sometimes actions speak louder than words.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout