Quest to recognise unsung cyling hero Margaret McLachlan

Margaret McLachlan knows all about fairness. At the height of her powers, she was banned from competition simply for being a woman.

In a tidy Central Coast bungalow framed by mandarin trees, where the quiet town of Cooranbong huddles in the shadows of the Watagan Mountains, one of cycling’s unsung heroes is cutting up cake and travelling through time. Back past recent controversies of transgender women in cycling and through the modern day exploits of the women’s pro tour, back past track legends like world champion Anna Meares, and on back past the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, when women’s cycling was finally recognised. Way back past carbon fibre and Lycra to an era of wool and chamois, when steel was real, gears were rare and wheels were fixed, when training meant night rides, catcalls from cars and dodging projectiles. Back through the casual sexism and redneck repartee of 1970s Sydney, to the 1960s, when Margaret McLachlan was banned from the sport she loved for the crime of being a woman, and being too damned good.

Margaret’s story is one of talent denied, twists of fate, being born out of time. She could have been a contender. Hell, she could have been a world champion. A cycling prodigy and a physical specimen whose lung capacity blew the needle off the chart when she did an asthma test long before anyone knew what VO2 max was, who would race against – and sometimes beat – the best male cyclists Sydney had to offer while setting distance records that would turn most legs to jelly. Who worked full-time as a pharmacy assistant in Sydney’s CBD, came home and cooked dinner then set off solo into the Sydney night by dynamo light on a converted steel fixed-wheel track bike, racking up 500km a week. Until it all came crashing down in a perfect storm of cultural cringe, priggish officialdom, bruised male egos, fear of the unknown and plain pig ignorance.

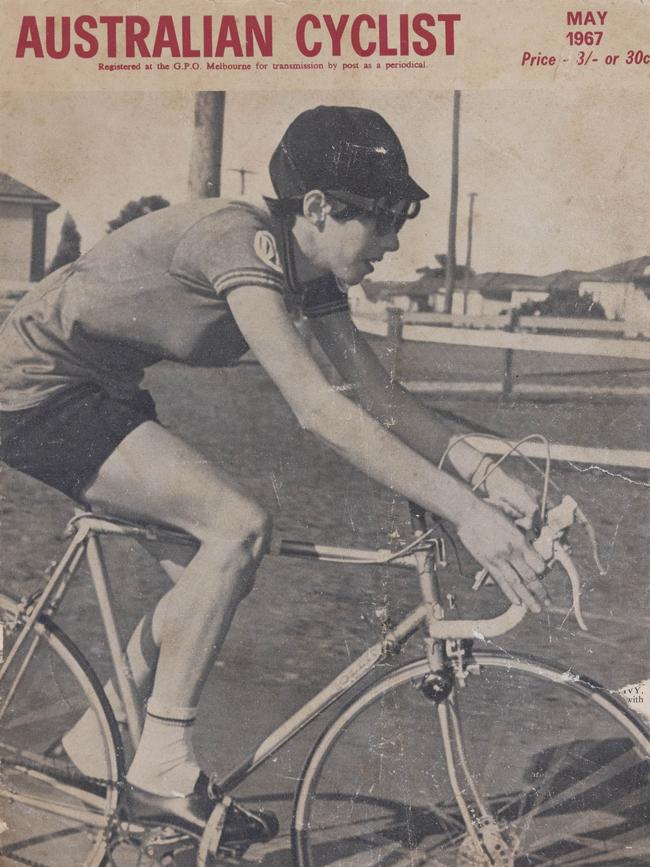

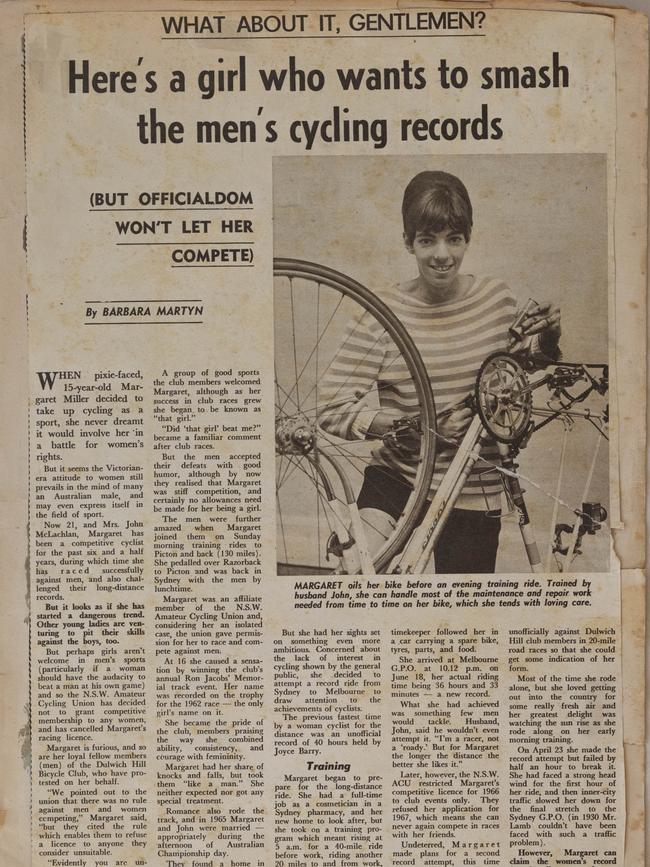

Twin stories in the Australian Women’s Weekly and Woman’s Day from May 1967, magazines that in that era were better known for tales of homemakers, knitting patterns and recipes for scones, set the scene. The former asks: “What about it, gentlemen? Here’s a girl who wants to smash the men’s cycling records … but officialdom won’t let her compete”.

The latter is punchier: “Girls are out!”. According to Woman’s Day: “After mud wrestling and the roller game, championship cycling must surely be one of the most unappealing activities a girl could indulge in. But Margaret McLachlan likes it – and therein lies the problem. She has been forbidden by the NSW Amateur Cycling Union to take part in official races because she’s a girl.”

In the Women’s Weekly: “When pixie-faced 15-year-old Margaret Miller decided to take up cycling as a sport, she never dreamed it would involve her in a battle for women’s rights. But it seems the Victorian-era attitude to women still prevails in the mind of many an Australian male … Now 21, and Mrs John McLachlan, Margaret has been a competitive cyclist for the past six and a half years, during which time she has raced successfully against men and also challenged their long-distance records … ‘Did that girl beat me?’ became a familiar comment after club races.”

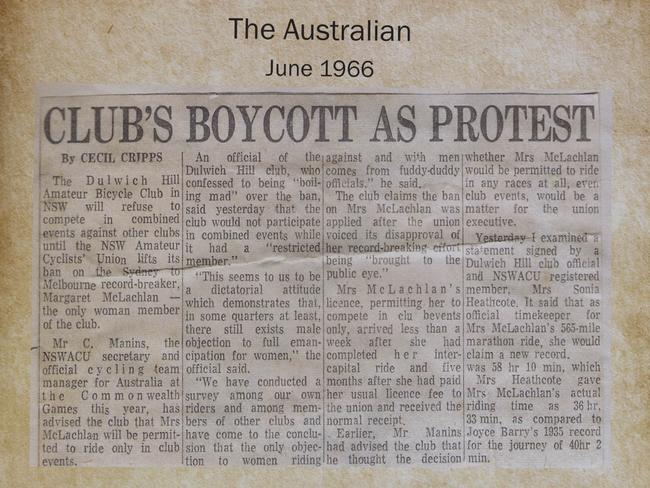

Marc Receretnam, cycling historian anduntil recently a member of McLachlan’s former club, Dulwich Hill Bicycle Club in Sydney’s inner west, is outraged by her treatment and on a mission to set things right. Along with Dulwich Hill Bicycle Club officials, he has launched a petition to have her achievements recognised by the sport’s national body, AusCycling, not least the women’s endurance records she set in the late 1960s, plus the women’s track hour record, none of which were ever officially ratified despite being conducted with support vehicle, witnesses and official timekeepers.

“A formal letter was sent to AusCycling’s CEO Marne Fechner and its board chairman Craig Bingham in February 2023,” says Receretnam. “Margaret’s racing licence was restricted in 1966 and she was given a full ban in 1967. No formal reason was ever provided, although Charles Mannin [the long-time secretary of the NSW Amateur Cycling Union] did admit, ‘We don’t permit women competitors, we don’t think we’re any different from any other sporting union in this. Can you think of anywhere women can compete against men?’”

The NSWACU, Cycling NSW and AusCycling have never acknowledged McLachlan’s record achievements. These include:

1. June 16, 1966: Sydney to Melbourne. Elapsed time 58 hours and 33 minutes.

2. April 23, 1967: Canberra to Sydney. Elapsed time 12 hours, 5 minutes, 19 seconds.

3. July 21, 1968: Sydney to Newcastle. Elapsed time 6 hours, 14 minutes, 30 seconds.

4. February 3, 1968: First Australian Women’s 1 hour unpaced track record. Elapsed distance 20 miles and 717 yards (32.8km).

“The NSWACU was formally approached to oversee these events but declined every time,” says Receretnam. “Copies of all official timekeeping records and formal documentation were supplied to AusCycling in late 2022. Margaret was given the OAM for her contribution to Australian women’s cycling in 2000 and she was co-founder of the NSW Women’s Commission with Gai Cridland in 1980. I’m certain we would all agree the world has changed since the 1960s. Exclusion and sexism can have no role in our modern society and it is incumbent on us to right these wrongs where we can.”

McLachlan, 79, finishes cutting up the cake she has just baked and pours coffee. Her trim frame is testament to the 40km she still cycles several times a week; her dark eyes twinkle and she has a laugh that starts somewhere deep within those famously capacious lungs. She is somewhat bemused by all the fuss, but also reckons “it’s about time” her feats were recognised.

Fair is fair, she says. The irony of the recent landmark Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) decision to ban transgender women who have been through male puberty from racing against biological females is not lost on her, given her own battle of the sexes. She is in favour of the new guidelines. “I always found it harder racing against men, especially on velodromes,” she says. “They are biologically stronger than females so I don’t agree with [transgender women in women’s racing].”

We sip our coffee and go time-travelling again. “How did I get into cycling? I used to go ice-skating, and one day at the Five Dock ice rink I met this guy, John.” He would later become her husband. “He told me he was a racing cyclist and took me to watch the racing on the track. And I said, ‘Oh yeah, that looks all right.’

“So he made me a bike up out of his old parts, with a second-hand frame, and took me for a training ride. We did 20 miles. That’s enormous [laughs] ... fixed wheel, toe clips, and I’d never ridden before. I was going down this hill and my foot slipped out of the pedal, so I had one leg sticking out and one going round and round but I didn’t fall off. Then we went up a hill and my feet were strapped in tight and I just toppled over. Had to walk up the hill. But I kept going. And that was my introduction to cycling.

“I kept riding, kept getting better. Then John asked Dulwich Hill if I could ride with them. They used to race Saturday afternoons on a road course out at Revesby [in Sydney’s west]. So they put me in with the juveniles first, then the juniors, and soon I was racing the men. I was so competitive. If someone was in front of me, I just had to catch them,” she recalls, laughing.

“Sunday was the big training ride, so we’d meet at Milperra, I’d ride and meet them there, then we’d ride out to Camden and back through Campbelltown, and wait while the fast guys went on to Picton. And then one day I thought, ‘I can do that.’ And I kept up, too. When my sister moved to Bargo, I’d ride from Coogee to Bargo and back, that was about 200km. I’d stop for tea and then head home. Razorback [between Camden and Picton] was my favourite climb.”

The racing ban came out of the blue. “Of course it bothered me. They were worried that if they let me keep racing, then other women might want to ride as well. And we couldn’t have that now, could we?” This was an era, she points out, when women weren’t allowed run in marathons as it might affect their child-bearing capabilities; an age where she had to threaten to punch a reporter to make him stop referring to her as a “Sydney housewife”.

The long distance record attempts were her husband’s idea, by way of revenge. “It was in the papers that some Boy Scouts had ridden from Sydney to Melbourne in four days. John said, ‘You could do it faster’.” Her first distance record attempt was uncharted territory, a steep learning curve and hell on two wheels. “I didn’t know about the right sorts of food to use on a ride like that. I finished up with an acid stomach and the acid was actually coming up and it burned my tongue, it was like that all through the last day.

“My bike was a converted track bike – not the most comfortable set-up for long distance. And we only had five-speed gears. All the blokes said, ‘Oh, she won’t get up Mt Jugiong [a steep pinch of around a kilometre with an average gradient of 8pc, between Yass and Cootamundra]. But they timed me in the car and I didn’t drop below 12mph [19kmh].”

Canberra to Sydney, she was on a mission to match male champion Richard ‘Fatty’ Lamb’s record. “He went through Bowral so I did the same. It was hard, dead roads, very tough. I missed out on his record by about half an hour, but set the women’s mark.”

Sydney to Newcastle, she recalls, “was funny as I wanted to ride over the Harbour Bridge on the roadway. So I rang the tollmaster and asked for permission. He said no, unless you’ve got a police escort. So I rang the traffic police, and they refused. It was early Sunday morning, and I just rode through the toll gates anyway. What were they going to do? [Laughs] Around Wyong a group of cyclists came out to meet me, and the police were going to stop us for disturbing the traffic. I just kept going. In Newcastle, a bike shop owner I knew had people on every corner to stop the traffic so I could sprint through town.”

Most painful was her one-hour track record. “It was an old wooden velodrome in Melbourne, very rough. I was practising a few days before and my back tyre blew out at the top of the banking. I skidded down the track, ripped straight though my woollen shorts and ripped a four inch square patch of skin off.

“I went to the chemist and bought some parrafin gauze and ointment, and went for a 20-mile ride on the road so I wouldn’t stiffen up. By race day the bruise was huge. It was a very slow track, the boards were loose, it was like riding over an old bridge so my time wasn’t great. And I had to do it at 11pm at night after the men’s racing had finished.”

After everything McLachlan’s been through, you would think it would be a simple matter to finally put her deeds up in lights. Recertnam blames official apathy, buck passing, head burying and the confused period where two years ago AusCycling was set up to bring road cycling, track and BMX under one national body.

When the petition was launched, the state body, NSWACU, sent a letter to more than 20 cycling clubs, suggesting McLachlan’s achievements did not deserve special mention and instead all clubs should recommend female cycling pioneers for recognition. “Given you are asking for old record holders and past results to be acknowledged as Margaret’s distance was broken (in the one-hour track record) some months later, I expect you are chasing a list of all successful attempts … of course road records are a minefield as between the wars there were some amazing feats by female cyclists.”

Recertnam said he had been shocked and disheartened by this response. “Margaret was the rider who was actually banned from the sport, and it’s a wrong that needs to be put right. Of course there are other female riders of note from the old days, and that is a matter for AusCycling and their heritage committee to recognise, but in my opinion Margaret is a special case and was the victim of a cruel injustice.”

David Dight, president of Dulwich Hill Bicycle Club, agreed, and said the club, which recently voted to make McLachlan a life member, was 100 per cent behind the petition. “Margaret is a champion in many ways, not just on the bike, but for gender equality,” he says. “Our club is very proud of Margaret’s achievements. We are also talking to the Inner West Council about a special acknowledgment of Margaret as a local hero and role model.

“Like many sports in this country, cycling has a patchy early record when it comes to inclusion and equality. DHBC believes it is time to revisit the past and set the record straight. Our sport and the wider community will be stronger as a result.”

AusCycling’s Marne Fechner denied the body was ignoring or stalling on the bid to recognise McLachlan’s achievements, but needed “a bit more time” to investigate and take action. “Our heritage group has set up a committee to look into this,” she says. “It’s an amazing story to be told. We are close to launching our inclusivity and diversity policy for the sport, and Margaret’s story is a great example that should be honoured. There is no question we want to support the petition. The records have been provided to us, and there is now a technical process to investigate but I am confident this recognition will be forthcoming in the near future.”

On the vexed question of transgender women in cycling, Fechner says AusCycling is aware of the UCI decision and is monitoring developments, but the body has not yet decided if it will follow suit: “This is a complex issue, and we want to ensure we take a thorough, well-informed approach,” she says. “We don’t currently have a specific policy regarding the participation of transgender athletes in cycling events, however we’re in the process of establishing a working group that will be charged with drafting our policy.”

We finish our coffee and cake and Margaret takes me into her garage to show me her bikes. There’s a Cervelo R3 road bike, a mountain bike, an old steel touring bike, and a prehistoric looking indoor trainer her late husband jerry-rigged that she says gets the job done when it’s raining and she wants to train.

“Look, it’s not the end of the world if they don’t recognise my records. But they probably should,” she says. “I do feel a bit cheated. By the time the sport officially recognised women, it was way too late for me. I was still racing, but I was riding against people 20 or 30 years younger. I did still get some places, by the way. I was still racing A grade at 38, 39 years old.”

The gear has changed over the years. “Rims are much better, and wheels are much stronger,” says McLachlan, who for years was a qualified mechanic and owned bike stores in Stanmore, in Sydney’s inner west, and later in Newcastle. “Handlebar tape, so much better now. Lycra, boy what a revelation! Wool got wet and very heavy in my day. Gear shifting on the brake levers. And clip-in pedals.”

She still does her own maintenance and repairs, builds her own wheels. And while she might go a bit slower than in her heyday and huff and puff a bit more up hills, the competitive spirit remains. “I usually ride by myself these days. But if I see someone on a bike up ahead, I still want to catch up and pass them.” she says, laughing. “And I usually do.” b

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout