Jail time, dodgy deals: the perils of doing business in China

Hanging by his arms, handcuffed to the gate of a Chinese prison cell he shared with 20 other men, Anthony Fellows was sinking into a physical and mental abyss. How did the WA cattle boss get here?

Hanging by his arms, handcuffed to the gate of a Chinese prison cell he shared with 20 other men, Anthony Fellows was sinking into a physical and mental abyss.

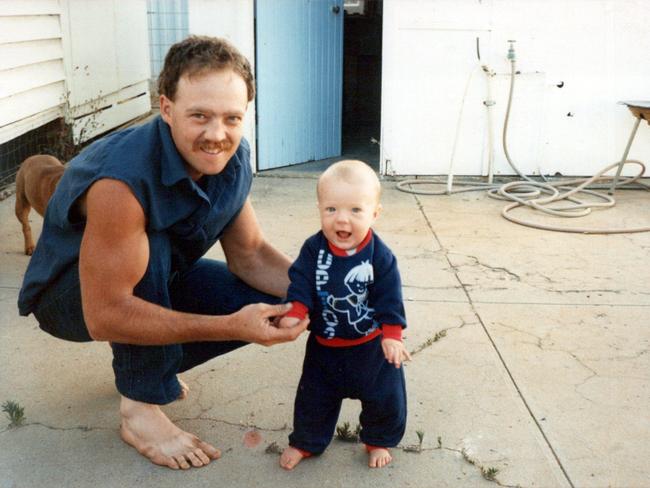

Fellows, a fourth-generation farmer from WA who had built an executive career in the live export cattle trade, was in his second week behind bars after he was unexpectedly taken in for questioning over accusations he had committed tariff fraud. Unable to contact his family, and facing a legal system in which it is almost impossible to be acquitted, Fellows was grappling with the prospect of spending a decade of his life in squalor in a Chinese jail.

Right now he was being punished over his failure to stand to attention when a prison guard had entered his cell. Fellows and his cellmates had been in the middle of a designated period in which they must sit cross-legged, a position that Fellows – his knees already shot after a lifetime on the land – found difficult to maintain. His legs had seized up, and he’d struggled to get to his feet fast enough.

His punishment for that act of disrespect was to have one arm passed through the cell door above the uppermost horizontal bar, his other arm under the door’s lower bar, and then handcuffed together on the other side. The awkward position was tolerable for the first few minutes, but the lactic acid began to build and his legs began to ache.

It was at that moment that he felt a cellmate put his leg underneath his lower body, helping support his weight for a few precious seconds before the guard could spot what was going on. A few minutes later, another inmate did the same. Beyond the immediate albeit brief physical relief, the support was a reminder that despite the vast distance from home, despite the apparent hopelessness of his situation, despite being a foreigner, he wasn’t totally alone. “I’m just some caucasian bloke in the cell, they didn’t have to do that for me,” Fellows, now 59, says. “That was probably where I still felt real.”

Until now, Fellows has never spoken publicly about his first-hand brush with the innermost workings of the Chinese justice system and a fretful, one-month stint in jail in 2015.

The series of events that led him to that jail cell began months earlier, when a spike in cattle prices had briefly opened a window where money could be made from the import of crossbred dairy cattle into China. The China market for crossbreeds had historically been uneconomic because of a 14 per cent tariff, but prices had swung in favour of the exporters.

Fellows’ shipment went off without a hitch. But in February 2015 he received an unusual phone call from one of the Chinese importing agents who had been helping his company. The agent asked him to prepare an amended contract showing that the crossbreeds were sold for $1400 each – a price well below their actual sale price. It was, the agent said, a special request from one of their clients. Fellows was circumspect but complied with the request.

“In hindsight, it definitely had hairs on it. But at the time, it felt no different to plenty of other deals in China,” he says. In the cattle export industry, it is not unknown for contracts to be renegotiated along the way. Markets can fluctuate significantly from the placement of an order through to delivery and payment, and, for the sake of long-term relationships, a price may be lowered or the timeframe for payment extended.

Instead, and unbeknown to Fellows at the time, the contract request was aimed at trying to shift the blame on to him – an innocent third party – for a tariff fraud that the agents had orchestrated.

Two weeks later, Fellows received another phone call from one of the agents asking him to come to China right away. When asked what was happening, the agent said he couldn’t talk about it but would explain once he got there. “My mate Robbo said, ‘You’re not going to end up in jail are you?’ I said, ‘Send me some red frogs if I do’,” Fellows recalls.

Fellows’ destination was Zhenjiang, a second-tier port city upriver from Shanghai through which Central Pacific Livestock – the company where he was the managing director and joint shareholder – regularly shipped cattle.

On the night he arrived at his hotel, Fellows was met by a group of lawyers for the importing agents. They informed him that two of their clients had been taken into custody by China’s Anti-Smuggling Bureau, and they questioned Fellows until 1am. As the meeting finally wound up, Fellows pulled out the copy of the amended contract that he had been requested to bring and asked the lawyers what they wanted him to do with it. They told him to just leave it in his briefcase. The next morning, one of the women from the import agent called and asked him to meet her in the lobby.

As soon as he walked up to her, three men approached. One of them introduced himself as an inspector with the ASB. “He said, ‘We’d like to talk to you, we want to take you back to headquarters’,” Fellows recalls. “I said, ‘Am I under arrest?’ and he said, ‘Only if you refuse to come’.”

Fellows was handcuffed and his mobile phones were seized. He was then taken to the headquarters of the Anti-Smuggling Bureau in Zhenjiang’s city centre. It looks like a typical Chinese government building, with its wide street frontage and its solid granite tiling, but Fellows’ anxiety began to rise as he was taken in a lift down to a basement interrogation room. The room had video cameras at one end, and what Fellows describes as a set of medieval stocks at the other. He was shackled to a chair and fitted with ankle bracelets, and spent the next 12 hours being questioned.

“At 10 o’clock at night they said, ‘Right, we’re going to go and decide what’s happening with you. And if we think you’ve been truthful, you’ll go home. If you haven’t been truthful, you’re going to prison’,” Fellows says. “At that point they picked up my briefcase, opened it up, reached in and pulled out that contract. He knew it was there because there was plenty of other shit but he just pulled that straight out. And he said, ‘I think you’ll be going to prison’.”

The Chinese import agents, he realised, had been reporting a lower sale price to the authorities so they could skim the difference between the actual tariff and the declared tariff. That one bit of paperwork pointed to Fellows also being part of the scheme, even though the terms of the contract meant it was the agents, not Central Pacific Livestock, that was liable for the tariff – and his firm therefore had nothing to gain by manipulating the numbers.

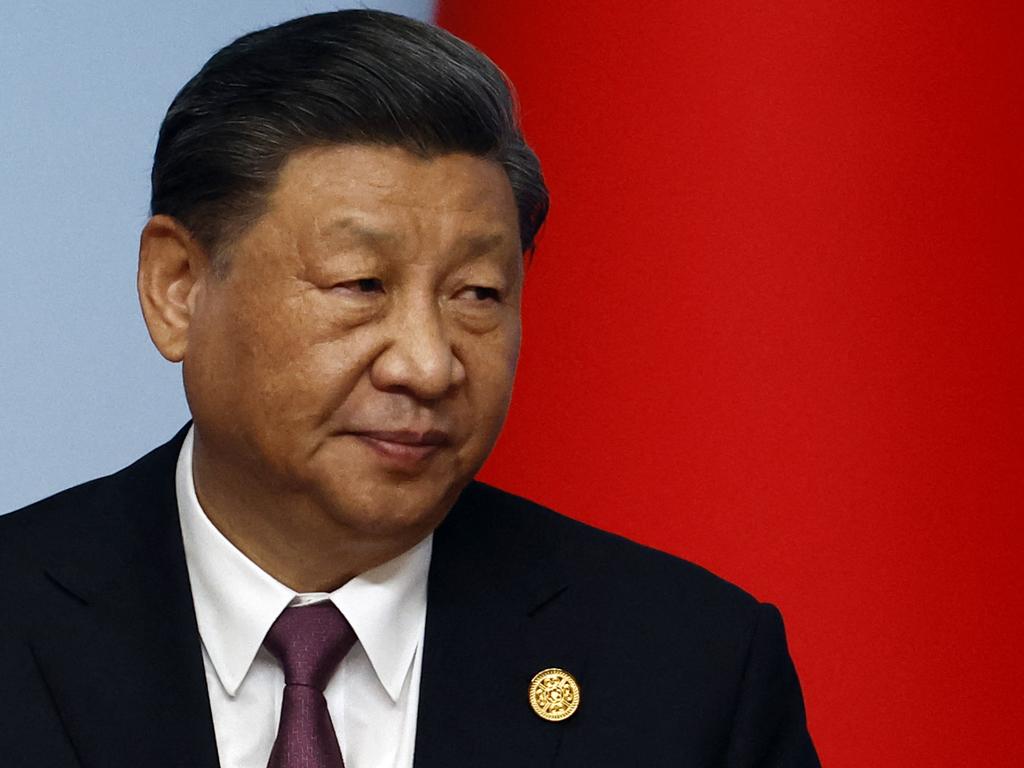

China’s prisons are notorious, and international human rights groups have raised concerns about China’s treatment of prisoners for many years. While it is rare for Australian businessmen to find themselves in legal trouble in China, it is not unheard of.

Perhaps most famously, Rio Tinto executive and Australian citizen Stern Hu spent nine years in a Chinese jail after he and three Chinese colleagues were convicted in 2009 of accepting bribes and stealing state secrets. In 2011, Australian entrepreneur Matthew Ng was sentenced to 13 years in prison on embezzlement charges, and 16 China-based staff of Australian casino giant Crown were jailed in 2017 over illegally promoting gambling. The number of Australian business people caught up in China’s legal system has eased in recent years – but Australian writer Yang Hengjun and journalist Cheng Lei are both still in prison after being arrested in 2019 and 2020 respectively on national security charges.

On that night in 2015, Fellows was pleasantly surprised when he was taken to a modern, clean and well-lit facility. He was led into a bright foyer, and remarked to the police officer escorting him – who had some broken English – that the prison looked very good and very clean. “He looks at me and he says, ‘No, this is a hospital. We need to make sure you won’t die’.”

While the Chinese police officers were worried about his physical health, it was Fellows’ mental wellbeing that would be of greater concern. Years earlier, he had “fallen off the face of the Earth” when the stresses of almost 20 years managing the huge Meka sheep station became too much for him.

Life on that station, inland from Geraldton in Western Australia’s midwest, was hard work in a tough environment with no support. Over time, the pressures on Fellows grew and grew. His wife Anthea became increasingly concerned that he might hurt himself. “One day he just walked off into the bush and I didn’t know if he was dead or alive,” she says.

It came to a head in 2002. “Every year, so many f..king sheep died,” Fellows says. “It didn’t matter what you did, they just died. So after about 18 years of that, one day I decided to fly an aeroplane into a rock. But I chickened out.”

They left the station and moved to Geraldton, with Anthea starting work in the airport cafe while Anthony recovered. He eventually found his way back into work, starting off as a humble farmhand at a nearby station.

He returned to a managerial role when that station was acquired by a larger agricultural group, and started to become exposed to the live export trade. The world of live export – its complex negotiations with deep-pocketed buyers in exotic locations – quickly became addictive: the deals were big, the stakes were high, and Fellows was good at it. He swiftly rose to an executive level, eventually joining one of Australia’s biggest live exporters.

One day, sitting in the company’s private jet as he flew to a meeting with a major buyer in the Middle East, Fellows looked out the window across the horizon back towards the WA coast. “I sat there thinking about how a couple of thousand kilometres that way was Meka station, and by f..k this is a long way from Meka.”

While Fellows’ professional fortunes and status had changed dramatically, he had never sought proper, long-term help for his mental health. Those mental susceptibilities were still there years later in China as Fellows made his way from the medical check to Zhenjiang’s municipal prison: a facility that was far more in keeping with his original expectations.

He was handed two blankets and a prison uniform and was led to the 8x6m room that would be his home for the indefinite future. Low wooden benches that doubled as beds ran down each side, and at the far end was a squat toilet. A three-foot gap between the top of the walls and the roof meant the prisoners felt the full force of Zhenjiang’s cold winters, where the temperature often falls below zero.

At night, the prisoners could fit three abreast on the benches if they stayed on their side.

“There was this big guy in there that I used to call Panda, because he looked like a panda,” Fellows recalls. “The first night he half cuddled up to the back of me and f..k I jumped. By the second night I realised he was just trying to stay warm and he had a good body mass.”

On his first morning in the cell, a spigot in the wall near the squat toilet burst forth with a stream of warm water. All the prisoners swiftly stripped off to bathe themselves, and Fellows didn’t hesitate to rush in. The sight of his hairy chest acted as an icebreaker.

None of the other prisoners were fluent in English, but most of them each knew a few words. Working together, they were able to find a way to communicate with their new cellmate and over time Fellows was able to understand why each of them had wound up in prison.

The oldest man, in his seventies, had fallen asleep while driving his auto rickshaw one night and had run over and killed a woman. One man was behind bars after his taxi business went broke. Panda, Fellows learned, had been imprisoned after beating five people to death with a lead pipe. Two young boys aged no more than 14 – the minimum age at which offenders can be sentenced to adult prison in China – were there for pickpocketing and drug dealing.

Discipline within the cell was, in the first instance at least, handled by the inmates rather than the guards. That first night in prison, as he began to spiral into hopelessness, the tears rolling down his face were met with a stern intervention. His fellow prisoners made it clear that crying was not acceptable. “I knew the reason after the first couple of days, because everybody in there has got their problems, everyone feels like that, so if anyone shows some tears at all, then it would permeate the whole cell,” Fellows says.

The cell itself was lit 24 hours a day, and inmates were forbidden from covering their faces while they slept. So accustomed did Fellows become to the conditions that he says he still sleeps with a bathroom light on.

Cut off from the rest of the world, Fellows had no idea of the efforts that were going into helping him. Anthea had realised almost immediately that something was wrong after her husband did not call or message her or any of his work colleagues on that first day in China. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade began the process of trying to find him, checking numerous hospitals and prisons before finally getting his location confirmed after a week. Central Pacific Livestock called in top-tier law firm King & Wood Mallesons, and on his eighth day behind bars Fellows was taken to a room to meet his lawyer for the first time.

Back in Perth, Anthea felt lost. “My little dog was only six months old, she would sleep on the pillow and I would hold her and sob. I used to take her for walks through the bush and just cry. It was awful,” she says.

Fellows, meanwhile, tried to fall in line with the “no tears” edict of his cell mates. But even with the language barrier, his mental decline was clear. In his third week behind bars he was led by the guards to a small office, where they used Google Translate to inform him that he “was looking very sad”. He responded that he didn’t know what was going to happen to him, he was sick of sitting there, and he wanted to see his family.

“They looked at me and then said, ‘What you have done is very serious. You could be here for a very long time. You should try and remain happy’, and offered me a cigarette.”

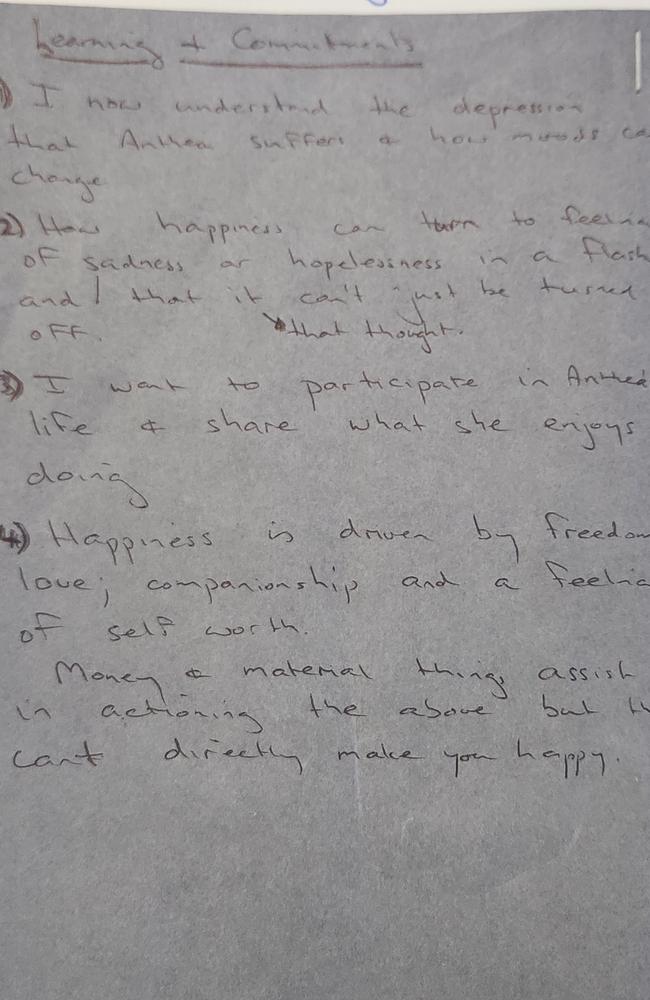

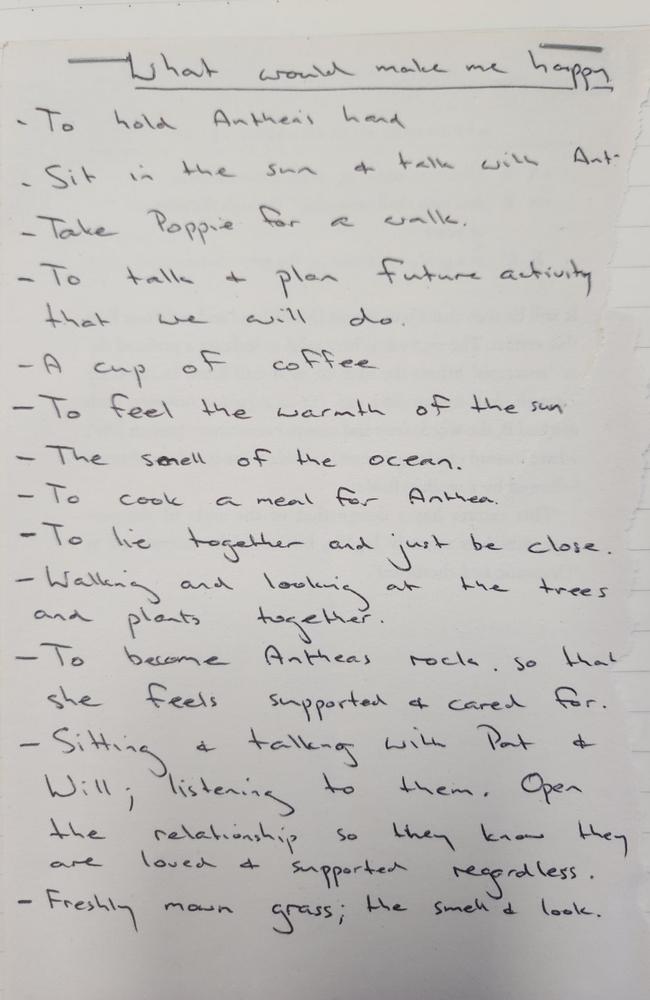

That conversation sent Fellows to rock bottom. “The human brain can be a f..king evil thing. Because you’d be sitting there asleep or eating your rice or whatever, and then this little thought would pop up about how I might never see my sons get married and it would just fester,” he says. Amid that mental darkness, torn up by regrets, Fellows began to formulate a vision for how he wanted his life to be. His son Patrick had sent a bundle of books to the prison, but only one – a book of verse by JRR Tolkien – had been approved by the guards. Fellows tore out some pages and borrowed a pencil from a guard to write down some of the thoughts that had been swirling in his head.

He wrote that he wanted to be a person who showed compassion and understanding, and who could be firm but not aggressive. Those prison cell jottings represented an extraordinary shift for a self-described workaholic who had always put his job above all else.

Fellows’ time behind bars came to a sudden end when King & Wood Mallesons managed to secure bail and a commitment for him to remain in the city under house arrest. He received psychiatric therapy to help dig him out of his mental “black hole” and prepare him for the possibility that he may be required to return to prison. His time in limbo came to an end when ASB investigators unearthed documents held by the importing agents on which Fellows’ signature had been forged, effectively proving he had no involvement in the tariff manipulation. At 10pm one evening, two months after he had been placed into house arrest, he received a call informing him he was free to go.

One of the Chinese agents was charged, but because of their lack of a criminal record was put on a three-year good behaviour bond.

Before Fellows left the country, he had to write a letter of regret – apologising to the ASB and vowing to learn from the experience, while being careful not to say anything that could prompt them to reconsider charging him.

Fellows had learned the hard way about the vagaries of justice in China; there is no lawyer-client privilege and 99 per cent of people who are charged with a crime are ultimately found guilty. And it had been enough to dramatically reshape him as a person. “It made me think about all the things I probably hadn’t done right,” he says. Pre-China Anthony, as he refers to himself, was a “prick of a bloke”. He was an old-school farmer who took pleasure in bringing employees to tears. More than once, he would sack a worker on a Monday to help ensure the others spent the rest of the week on their toes. While he was hard on his staff, he was even tougher on his family.

After his time in prison, however, those close to Fellows could see the change immediately, and Anthea believes her husband’s time behind bars probably saved their marriage. “I don’t think we would be together today if he had come back the same,” she says.

While under arrest, he had felt acutely aware of his lack of a physical connection to his wife and children. His answer to that was to get tattoos down each ribcage: he has the Fellows family crest and the names of his sons on the right flank, and on his left he has a tattoo of two ants on a leaf boat – a symbol of Anthony and Anthea together on the journey of life.

Remarkably, despite his experience in Zhenjiang, Fellows was not done with China. The international cattle trade was still his passion and his biggest professional strength, and he was not prepared to walk away from that. Within a year he was back in China.

Since the drama of Zhenjiang, the road has not been smooth for Fellows. In 2016, Central Pacific Livestock rebranded as Harmony Agriculture and Food Company. Backed by billionaire Chinese investor Wenfang Wang, the company mission was to support the development of a fully integrated China-focused live export business.

But in 2019, Fellows found himself teetering on the brink with Harmony, which had been tipped into receivership and liquidation after its grand plans to leverage off China’s growing demand for beef had turned to tatters. Chinese authorities had changed their interpretation of their quarantine rules, drastically complicating the volume and pace at which Australian cattle could be imported. Harmony had already sunk tens of millions of dollars into readying its business to deliver cattle under the previous quarantine interpretation, but there was no way for the company to generate the levels of cashflow it had been betting on.

While Wang was supportive, Harmony’s main creditor was under financial pressure and reluctantly pushed the company under. Fellows spent a gruelling two years working to pull Harmony out of receivership. He was almost there in March 2021, requiring a court order to approve the company’s plans, but the registrar hearing the case ruled against them. Until that point, Fellows had been certain that Harmony would make it out of liquidation. Now, he suddenly doubted it would ever happen.

He shut himself away in his office and howled. For a mad moment he wondered how hard he would need to throw his chair for it to smash through the window. If he could succeed in breaking the pane, he reasoned, he could jump out the window and down onto the pavement below. The corporate collapse was a brutal blow to someone who was so heavily invested – financially but also mentally – in the business.

His time under arrest had been bad – but this time, there was much more at stake than just his own freedom. Staff, investors and suppliers were relying on him to save them – and everything he owned, including the family home, was on the line.

Ultimately, Fellows’ China experience was key to surviving the crisis. It brought him some much-needed perspective – more than once, close friends would say, “Well, at least you’re not stuck in a Chinese prison eating rice” – but more importantly, it was a reminder of his own fortitude and his ability to pull through periods of extreme pressure. “I’m not saying I do it perfectly, but I do now understand how to manage my mind as such, and where I go and how I go and what the triggers are,” he says. “The receivership side was really tough, but I was better able to handle just the ongoing day after day after day of it. I knew in myself I could do it, because I had been through that other one.”

A week after his loss in court, Harmony was out of liquidation. Fellows personally provided the funds for a QC to take on the case, and the court agreed to lift the liquidation order. Today the business is steadily growing into the success Fellows has always hoped it could be.

Wenfang Wang remains Harmony’s key backer. He and Fellows have found a balance with each other. Indeed, Fellows enjoys an unusual level of autonomy for the Australian chief of a Chinese-backed company.

While he has put a great deal of effort into trying to deepen his understanding of Chinese culture, Fellows concedes that the more he learns, the more he realises how little he knows. “Over the past couple of years I have finally understood that I will never understand exactly how Wang thinks. I’ve accepted that,” he says. “It’s a bit of a corny way of saying it, but that’s been fundamental to being able to be successful in China. Ninety nine per cent of the people that work in China think they understand the culture and understand this and that. You don’t really know it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout