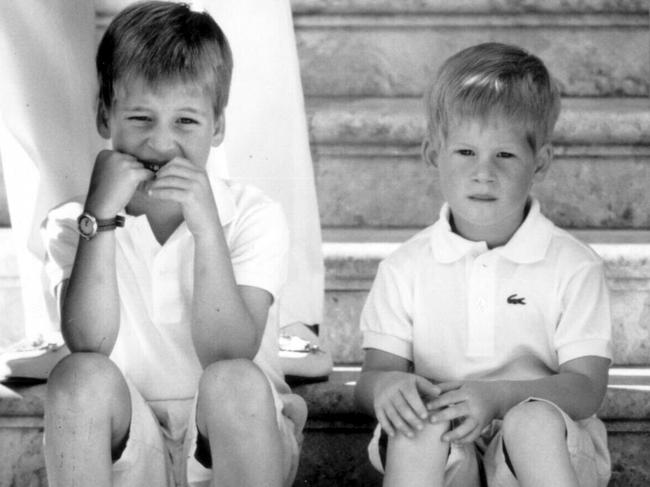

Prince Harry and William were not the first Royal brothers to go to battle

The newly published letters and diaries of King George VI and Edward VIII prove war between brothers in the House of Windsor is nothing new.

The former king Edward VIII left Britain after his abdication on the night of December 11, 1936, with a sense of unfinished business. While his younger brother, the new king George VI, tried to come to terms with what his unexpected reign would involve, Edward, now the Duke of Windsor, was preoccupied with two concerns: recognition for his fiancee, the divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson, and a desire that financial support should be provided for them both.

Thus on January 17, 1937, Edward wrote to his brother: “The events of December are past history and you and I have now only the future to look forward to – you have your life as king and you know how hard I have tried to make your succession as easy as possible – and I will throughout your reign (which I hope will be a long and a grand one) and for the rest of my life do all in my power to help and support you to the best of my ability.” The duke suggested that “for the first time in my life, I shall be very happy”.

What troubled Edward most was that he and his wife would struggle to find a new place in society, being quick to remind his brother: “Wallis and I have committed no crime … a lot of people are kicking us for the moment and you can stop it all – please do so quickly for our sakes and for our happiness and usefulness in the future – you can and you must do that.”

However, tension soon arose between the two brothers. The new king was preparing for his coronation amid rumours that he suffered from epileptic fits and wasn’t up to the job of ruling. He was a chronic stammerer, often relying on his wife in social situations. The duke occupied himself by telephoning his younger brother to tell him what to do and the conversations frequently ran into difficulty due to the king’s stammer and Edward’s fluency. The king soon stopped taking his brother’s calls.

The agreement struck between them at the time of the abdication at Edward’s country residence, Fort Belvedere, had been that he would receive an annual allowance of £25,000, paid from royal finances rather than by the nation. This would keep it a family matter and remove any danger of taxpayers subsidising Wallis, who was largely blamed by the public for the crisis. However, this had not been officially finalised and the delay made the duke suspicious. It did not help that the details of the agreement had been leaked to the papers. The king complained to the duke: “I haven’t told anyone that we even signed [an agreement] … this is now public property & it is very unfortunate at this moment when the Civil List is just coming up.”

He also knew that the duke had private savings stashed away. He suggested: “There is certain to be enquiry as to what has happened to the savings from the Duchy of Cornwall, before you came of age, & the rumour is that you have saved a very large sum from this source. You must tell me whether this is so, as I understood from you when I signed the paper at the Fort that you were going to be very badly off.”

Edward responded angrily to this. “You now infer that I misled you at that time as to my private financial situation. While naturally not mentioning what I have been able to save as Prince of Wales, I did tell you that I was badly off, which indeed I am considering the position that I shall have to maintain and what I have given up.”

He suggested, with veiled threat, that “I have kept my side of the bargain and I am sure you will keep yours… I should be very sorry and it seems quite unnecessary that there should be any disagreement between us over this matter – but I must tell you quite frankly I am relying on you to honour your promise.” He finally offered to rent his brother Sandringham and Balmoral, which he had inherited, for £25,000 annually.

Edward remained in thrall to Wallis, who referred to the king as “your wretched brother”. She suggested to her husband that, “If he continues to treat you as though you were an outcast from the family and had done something disgraceful and continued to take advice from people who dislike you… there would be only one course open to you and that would be to let the world know exactly the treatment you were receiving.”

Relations between the brothers were further strained when the king refused to offer the duke any official recognition of his impending wedding to Wallis, or to give her an HRH title. The king wrote: “I am very sorry that I cannot make the arrangements you would like about your marriage… The trouble is I can’t treat this as just a family matter however much I want to… In spite of the affection which of course there still is towards you personally, the vast majority of people in this country are undoubtedly as strongly as ever opposed to a marriage which caused a king of England to renounce the throne.”

The duke responded in a cold but civil manner: “I will never understand how you could ever have allowed yourself to be influenced by the present government and the Church of England in their continued campaign against me ever since I left in December… Their minds can now be at rest, because after this final insult, I don’t imagine that I shall ever have the desire to set foot in Great Britain again.” He ended with a personal attack. “I shall always be sorry to remember that you did not have the courage to give me the same support at the start of my new life that I so wholeheartedly gave to you at the beginning of yours.”

The king, meanwhile, faced more prosaic difficulties. He did not feel established or confident on the throne, and fretted about the responsibilities of his coronation. His assistant private secretary, Alan “Tommy” Lascelles, told Sir John Reith, the BBC’s director-general, in January that “the king was more fussed about his Coronation Day broadcast than anything else”. He knew his brother’s easy popularity with his people would be hard to replicate.

The coronation loomed before the king like a monolith. The service was scheduled for May 5, 1937, and Queen Mary, the brothers’ mother, was involved in the planning of it “with her characteristic vigour”. Yet the king’s stammer seemed an insuperable obstacle to the day’s establishment of him as the new sovereign. The ceremony itself did not worry him too much. Reith’s suggestion that it should be televised had been dismissed by Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Lang as sacrilegious, to say nothing of impossible to censor if the king’s physical twitches needed to be concealed. It was the subsequent speech on the radio that terrified him. Reith, who had organised his brother’s abdication broadcast from Windsor Castle, was keen, both for his monarch’s sake and for the reputation of the BBC, that the king should “make a good broadcaster”. He worked with speech therapist Lionel Logue and the BBC’s outside-broadcast engineer to make him feel comfortable enough to perform his speech live.

-

“I don’t imagine that I shall ever have the desire to set food in Great Britain again.”

-

Thankfully, both the broadcast and the coronation ceremony passed without difficulty. The king’s much-rehearsed speech, in which he declared how “with a very full heart, I speak to you tonight… never before has a newly crowned king been able to talk to all his peoples in their own homes on the day of his coronation” and told the nation that “the queen and I will always keep in our hearts the inspiration of this day”, was a success. Time magazine praised his “warm and strong” voice. Millions of his subjects sat at home listening to the broadcast, willing him to succeed while knowing of his stammer and the difficulties that even speaking a few short sentences publicly had caused him. The nation was relieved by the successful delivery of the first ever coronation broadcast.

It was known that Edward was sympathetic towards Germany, and seeing a business opportunity, his wedding host, the industrialist Charles Bedaux, took his chance to ingratiate himself with Hitler by suggesting a tour by the duke and duchess to Germany in the autumn of 1937. The pair agreed – the tour promised to be high-profile and flattering. The king informed his mother, “I have told my ambassadors that the embassy staff cannot help him in any official sense… the world is in a very troubled state, & there is plenty to worry about”.

The British ambassador to France, Sir Eric Phipps, was sent to see the duke and to dissuade him from being himself. He wrote in his report: “I warned His Royal Highness that the Germans are past-masters in the art of propaganda and that they would be quick to turn anything he might say or do to suit their own purposes.” Yet the duke was nonchalant. “He assured me he was well aware of this, that he would be very careful, and would not make any speeches.”

Even if this was true, there was dread in Phipps’s final line: “The duchess told a member of my staff last night that when in Germany they would be entertained by Herr Hitler.”

Yet for all his anger, the king could do nothing to prevent his brother from visiting Germany. Edward enjoyed his visit because it represented a change of scene and an opportunity to be feted, rather than merely tolerated, on the international stage. Wallis was pleased that she was referred to as “Her Royal Highness” at all times. On the penultimate day, they were received in Berchtesgaden, where Hitler had his holiday home. The visit was a propaganda coup for the Nazis and a PR disaster for the duke and duchess.

Back in France, the couple remained persona non grata. Fearing irrelevance, Edward wrote angrily to the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, to demand a date by which they could visit England.

Meanwhile, the matter of the duke’s allowance remained unresolved. A document drawn up on behalf of the king on November 22, 1937, agreed to its provision and in return that he would not return without official permission, stating: “There has been some discussion, and indeed some differences of recollection, about what passed when you left this country at the time of the abdication as to an assurance that you would not return here.”

In response, the duke huffed: “I should have thought that my record as Prince of Wales and as king was sufficient to convince anyone that I am a man of my word and that there was no necessity to impose financial sanctions on me.”

The king’s opposition to Edward and Wallis’s return came about from pragmatism. He worried that their return might confuse public opinion as to who was the “real” monarch. He was also jealous. His brother had always been able to make public appearances and speeches with aplomb, and Bertie (as the king was known to his family) had spent his life watching his charismatic sibling from the sidelines. The last thing he desired was a back-seat driver informing anyone who would listen how the new monarch was getting it wrong.

Even when Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938, few feared war would spread. Nevertheless, in the northern summer of 1938 it was decided the king would make his first state visit to France to strengthen the alliance. Edward hoped the visit would be an attempt at a reconciliation. The king had other ideas. He called the state visit “a most unsuitable moment for meeting”. The duke seethed. In a conciliation, the king finally got his brother’s allowance signed off. Edward wanted more, writing on April 30: “Dear Bertie, We would be less than human if we did not feel deeply all that has been done to us in the past sixteen months, and we naturally hoped for an end to such treatment,” before concluding that, “we do frankly feel that a formal reception given for us by your diplomatic representative in Paris is distinctly overdue to say the least”.

A compromise was reached. The British ambassador to France agreed to invite the couple for dinner, making sure high-profile members of the French government would be present.

“We do not mean to spend our lives in exile,” Wallis had once said, when asked why she and the duke had not considered purchasing a property in France. Their goods, which had once graced Edward’s beloved house, Fort Belvedere, were mainly stored at Frogmore, a villa in the grounds of Windsor Castle. They instead rented houses in Paris and Antibes.

Edward talked incessantly about when it would be his time to go home. Thus in August 1938, he again wrote to his brother: “One of the uppermost thoughts in my mind since I left England over twenty months ago has been to determine the most suitable opportunity for Wallis’s and my first visit to our country after our marriage… I have purposely remained abroad since December 1936, at great personal inconvenience, in order to leave the field clear for you. As there can be no doubt that your position on the throne is by now consolidated, and that consequently my presence in England can no longer embarrass you, we propose to come over on a visit next November.”

The king and queen discussed the request with Chamberlain. The king equivocated; he was not against the idea, but he had no wish for a return to take place as early as the duke’s hoped-for date of November 1938. The queen, meanwhile, was worried the duke would upstage her husband. It was therefore decided that it was impossible politically or socially for the duke to return.

This was not what Edward had expected. He might have been forgiven for scepticism at his brother’s assurance that “I naturally want your first visit to be a success, & one which would be devoid of any untoward incidents towards either of you”.

This letter had been considerably toned down. An angry draft that still exists in the Royal Archives spoke of how “during the last twenty months, while you, as you desired, have been enjoying the leisured life of a rich private individual, I have been endeavouring, to the best of my ability, to restore the monarchy to the position that it held when you succeeded, and to make good the damage done to it by the circumstances of your abdication”.

There was even a dig at Wallis. “The risk that [the duchess] might be insulted, either in public or private, does, I am afraid, exist, and it is of course for you to decide whether such a risk is worth taking.”

Thwarted by his brother, the duke turned to Chamberlain to support a return to England, now suggesting April 1939. He restated his request that Wallis should receive the title of Her Royal Highness, claiming that such a move “would go far to satisfy public opinion that good relations exist between us and the other members of the royal family”.

Chamberlain refused to offer any support for Wallis’s title (“It is essential that Your Royal Highness’ first visit should not become the subject of controversy”) and said that it was the king’s responsibility to deal with the matter. Instead, he suggested that a meeting with the duke’s younger brother, the Duke of Gloucester, in Paris would be a way of testing public opinion about the couple’s return to Britain.

The reaction to this meeting was not warm. The Gloucesters received more than 100 “extremely rude” letters complaining about the visit. It would fall to Chamberlain to break the news to the duke. He later reported Edward’s distress at the “mendacious and disgraceful” stories that had been spread about Wallis. Chamberlain ended by asking, “I suppose, sir, you would not care to come alone for the first visit?” Edward replied, “No, I could not do that: married people ought not to be divided.”

Instead, the duke put out a press statement: ‘‘I want to say how touched we are by the many expressions of goodwill… We had looked forward to making a short private visit to England in the spring, and should have done so had we not been informed that such a visit would not yet be welcome, either to the government or the royal family.”

The king fretted about what to do with his brother. The duke could not be allowed to remain in France if war broke out. On August 29, 1939, the king told his brother he would send a plane to collect him; Edward asked instead if he and Wallis could travel by destroyer, as befitted his status. HMS Kelly, captained by his friend Louis Mountbatten, was placed at his disposal. The duke and duchess finally returned to Britain the next month. But if Edward had expected that they would be greeted with regal fanfare, he was disappointed. As his wife remarked to him, “I don’t know how this will work out. War should bring families together, even a royal family. But I don’t know.”

Meanwhile, the queen fretted to Queen Mary that she had no wish to receive “Mrs S” as she had been so rude about them both.

Finally, a solution was decided upon. On September 14, a fortnight after the outbreak of war, the king received his brother at Buckingham Palace. It would be the first time the two men had been together since December 1936. Neither wanted to see each other. The king told his younger brother, the Duke of Kent, afterwards that the meeting had been reasonable but “very unbrotherly”, and that Edward had been “in a very good mood, his usual swaggering one, laying down the law about everything”.

-

“The whole world knows we are not on speaking terms, which is not surprising”

-

In 1940, the Duke of Windsor was posted to be governor of the Bahamas, then a British colony, after fears that he was keeping company with Nazi sympathisers in Portugal. It was here that he learnt the Duke of Kent had died in a plane crash in Scotland in August 1942 – George had been his favourite sibling. The funeral was held at St George’s Chapel in Windsor; Edward, inevitably, could not attend but the tragedy hinted at the chance of a rapprochement between the warring brothers. The duke wrote, “I share with you this irreparable loss.” Nevertheless, he could not resist a dig: “It is, therefore, a source of great pain to me now to think that on account of your ‘attitude’ towards me, which has been adopted by the whole family, he and I did not see each other last year when he was so near to me in America.”

By 1943, the duke and duchess were desperate to leave the Bahamas. The duke was offered instead the governorship of Bermuda, which he turned down. Furious, Edward wrote to his brother to lambast him yet again: “I have taken more than my fair share of cracks and insults at your hands… I suffered these studied insults in silence on the supposition that they were a necessary part of the policy of establishing yourself on the throne.” He even offered a veiled threat as to what he might be capable of in the future if his wishes were not acceded to. “The whole world knows we are not on speaking terms, which is not surprising in view of the impression you have given via the Foreign Office and in general that my wife and I are to have different official treatment to other royal personages.”

He concluded: “I must frankly admit that I have become very bitter indeed.”

“Being shut up here is like being a prisoner of war, only worse,” Wallis complained to her aunt in April 1944. She too was frustrated with the pettiness of her official role. It had also come as a shock to see herself denounced in a magazine as a grasping clothes horse. One anonymous Englishman even suggested that, should she return to Britain, she could expect to be stoned to death in the street.

It was not until October 5, 1945, that the Duke of Windsor returned to the UK again. By this time the war had ended and the country had a new prime minister, Clement Attlee. The king’s private secretary, Tommy Lascelles, felt trepidation about the duke’s return, not least because the duke had given some ill-advised press interviews, talking up what he expected to achieve from his visit. Nonetheless, as he wrote to the king, “The only person [these interviews] do any actual harm to is the duke himself… the general public are ‘fed up’ with such interviews… The only reaction of the average man is, ‘Here’s the Duke of Windsor talking to the press again. Why can’t he keep quiet?’”

The two brothers met for dinner along with their mother – the first time they had been in a room together since September 1939. The duke asked Queen Mary if she would be prepared to receive Wallis and, after a long silence, she answered that she would not. Edward now accepted that the duchess would never be received formally by his family or be awarded the title Her Royal Highness.

The duke had a subsequent meeting with his brother the following day, where the two men “discussed the whole matter very thoroughly and quietly”. The duke stated that he would not have been able to carry out his duties as monarch properly without his wife. The king informed Edward that any further job under the crown was impossible, given his previous status as sovereign.

When Edward met with Lascelles on October 9, the private secretary asked him, “In 1936, you made a tremendous sacrifice, on behalf of the lady who is your wife… Could you not now make another sacrifice on behalf of your brother who, nine years ago, took on the toughest job in the world… You know that your idea of being a ‘younger brother’ under the king simply wouldn’t work – wouldn’t it just be a good gesture on your part to accept these facts once & for all?”

Lascelles had, inadvertently, exposed the weakness of the royal family. “The Firm” could belittle the duke, patronise him and write him high-handed letters that refused to grant him the privileges that he requested. But he could not simply be expelled from his position. It might have made matters more convenient if he had renounced his title and lived as a private citizen, but as his great-great-nephew has subsequently discovered, a royal title is a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

Seven years later, in 1952, George VI died of lung cancer, leaving his elder daughter to become Queen Elizabeth II at 25. The Duke of Windsor returned to England for his brother’s funeral without his wife. He did not attend his niece’s coronation. He died in Paris in 1972 of throat cancer. Shortly before his death, the young queen briefly visited him while on a state visit to France.

Extracted from The Windsors at War: The Nazi Threat to the Crown by Alexander Larman (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $34.99), out now

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout