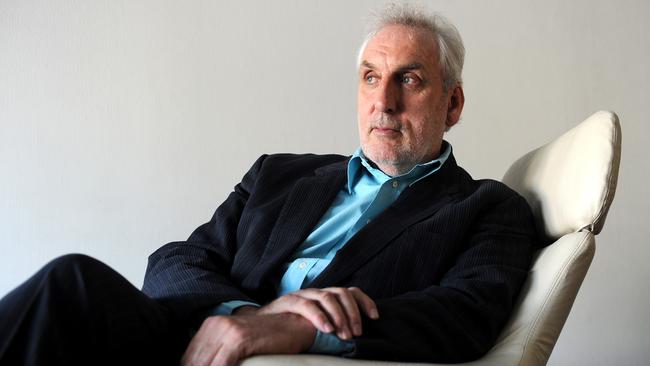

Phillip Noyce on his best films, bushfires ... and the ones that got away

When director Phillip Noyce left Los Angeles’ bright lights to come home and make Rabbit-Proof Fence, he came armed with a secret weapon he said would guarantee its success.

In 2002 you directed Rabbit-Proof Fence, regarded as one of the greatest Australian films of all time. Is it your best work? Oh, without a doubt. When [film producer] Christine Olsen woke me in the night and told me she had the perfect screenplay and I’d be the perfect director for it, my first feeling was “Why would I want to give up a career as a highly paid Hollywood hack and go and make this film about an Indigenous experience, when I know the Australian audience won’t want to see it?” But then I thought, I’d been in this pressure cooker of Hollywood all this time and I’d learned about using publicity. It was my secret weapon. The first person I hired on that project was a publicist, and she was still working on the film a year after it came out.

Is it true you usually cut the trailer before you edit a film? I’ve done that a lot in my career. It serves two purposes, it narrows your focus a little bit and it allows you to expose the financiers to what the film might be like – so they can complain now, not later.

Nicole Kidman got her big international break in a film you directed, Dead Calm. Did you foresee she would become such a star? Absolutely not. I mean, I did go into the bathroom at the Potts Point headquarters of the Kennedy Miller Productions studio, look in the mirror and say to myself, “You’re gonna do pretty well if you cast this young lady in your film”, but I thought that meant Australians would like it. I’d never imagined that film might become bigger than all of us. It’s true she walked into the audition and blew us away with her performance, which she’d already done six months earlier in a series we’d made called Vietnam. But no, I would never have imagined that her career would take her on to become the biggest thing on the planet.

She was 20 at the time of filming. Co-star Sam Neill, who played her husband, was 40. How did she bridge that age gap? We’d already cast Sam Neill and then we realised we had a star in the studio with Nicole and so, I’ve got to hand it to Nicole, because I said, “We want you to do it, but you’ve got to somehow grow up.” She changed her voice, she studied mothers, and she did elocution lessons. Before our eyes, she was able to play a person much older and the audience accepted them as a couple – and that’s because of her brilliance.

Have there been actors who you knew were destined for greatness? Well, sure there have been a few that impressed me – but there are also a lot of actors I wish I had cast but didn’t.

Oh, great! Tell us some of those. Well, I mean, Brad Pitt, that’s one of them. I was making a film with Sharon Stone, an infamous film called Sliver, and she was telling me about this young lad in her acting class named Brad Pitt and she’s saying we have to take a look at him, we have to cast him. I ended up casting somebody she did not get on with at all – Billy Baldwin – and she has never let me forget it. And I should have cast Russell Crowe as [the lead in] The Saint. Russell came in to meet me and said, “You know, I’m not there yet, but if you cast me in this role you’re gonna look really good because I’m going to the top” and I sort of couldn’t hold back my laughter but of course, he was completely right. I turned George Clooney down as well. And every time I see Timothée Chalamet, you know, I throw my hands against my head.

In the 1990s you were part of the big-budget Hollywood machine making blockbuster after blockbuster. What was that like? A lot of the work back then was done by the studio. They would buy the rights, they would handle negotiations, they would get the actors and look after the publicity. The studio sold the good films, and they sold the bad ones too. A lot of those films hit number one at the box office and that was not because I made great films. Some were great, some weren’t. It was because of the machine.

The machine as we knew it is no more. How has that affected your career? In some ways, I’m reborn back in the 1970s because you’ve got to do most of the work yourself, especially with distributing films via streaming, which has its huge advantage for world cinema. Although Netflix, Amazon and Apple, their main offices are still right outside my door here in Los Angeles, they’ve discovered they can make films in other countries that will be as successful as ones made in America.

Lots of people are lamenting the death of the cinema … There’s a lot to lament! I’ve spent the past two months – as we do here at this time of year in Los Angeles, if you’re in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences – watching about 200 films in two months. I’m either watching them on an iMac or on my 50-inch television or in a cinema on a 50-foot screen, and I know these films are completely different when you see them on a big screen. The immersiveness, the shared experience of the audience around you, is so much a part of the cinema that I grew up with. So that’s the disadvantage: what we call cinema is sometimes no longer cinema.

You’ve spent the last few months in LA during the wildfires. Have you kept safe? Yes, we’ve managed to avoid the fire where we are. I mean, we had the car packed with our valuables, passports, all that kind of thing, just in case. The experience did remind me of home. When I was seven, I accidentally started a fire that destroyed 1000 of my father’s chickens which he’d raised in this newfangled force-feeding system that had been introduced at the time, back in the 1950s. My little game with matches ended up with 1000 chickens being roasted.

Yikes! What was your punishment for that? I can’t remember particularly – but I do remember they put out my fire but then an hour later it came back to life with the October winds and started a bushfire, for which I suppose I was partially to blame.

Wow. Phillip Noyce’s former life as an arsonist. Is there anything else you’d like to get off your chest? Well, now you mention it, back in 1969, I was charged by the Sydney Vice Squad with smuggling an indecent publication. It was an underground newspaper called Ubu News and they’d sold an ad at the time to Levi’s Jeans. The image was a stick figure of a guy who had his jeans on his head which meant that everything below his tummy was naked – including his little “stick figure”. The judge agreed I had participated in perpetrating an indecency on the Australian people.

Fortunately, by the 1970s your criminal days had come to an end. SBS has dug up a series of films you made while working at Film Australia during that decade. What’s it like to watch films you made as a young man? I had been wondering for decades about those films, not least because one of them, a film called Mike, actually caused me to swear off documentaries completely and take up fiction filmmaking. Even though fiction films may be based on real events, at least they have plausible deniability for the maker – but the responsibility of making that film about kids who would bash homosexuals on a Saturday night for pleasure? I mean, the responsibility of telling that story just weighed on me too much. Watching some of this stuff back, it does feel very much like the last century. It’s a long, long time ago.

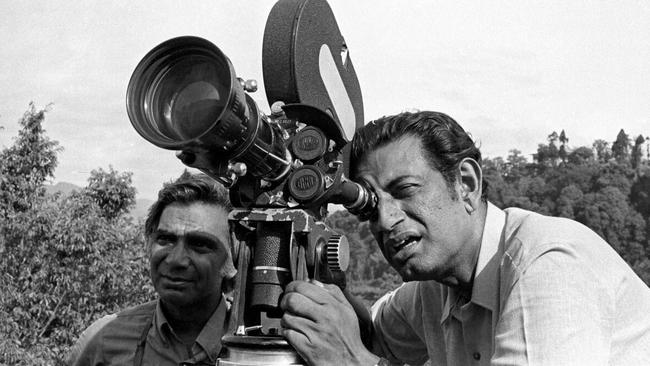

Filmmakers such as Peter Weir, Bruce Beresford, Gillian Armstrong and you were collectively referred to as the “Australian new wave”. What was a common trait you all shared? A lot of us were enamoured with the Italian neorealist filmmaker Vittorio De Sica who made a film called Bicycle Thieves [in 1948] and then in turn, the work of Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray who drew on real people to play themselves in his films, as opposed to actors. There was a great humanism in their films and I think no matter what we were making we captured that humanism too, which is also a part of the Australian ethos, the “fair go, mate” ethos. We also all inherited a can-do attitude because we didn’t have the kind of system they did in the American studios. If we went over budget there was nobody around to bail us out.

Phillip Noyce appears in the SBS documentary series Australia: An Unofficial History, which premieres on Wednesday at 7.30pm, and is available at SBS OnDemand

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout