Paulina Porizkova: I’m as invisible as any other 56-year-old woman

Walking into a party beside a supermodel is a terrible idea, but Paulina Porizkova is inviting me to do just that. She has a point to prove: “Nobody believes me unless they see it.”

Everyone knows that walking into a party beside a supermodel is a terrible idea, but Paulina Porizkova is inviting me to do just that. She has a point to prove. “You have to come with me,” she insists. “Nobody believes me unless they see it. My girlfriends thought I was joking at first. Now they’ve all witnessed it.”

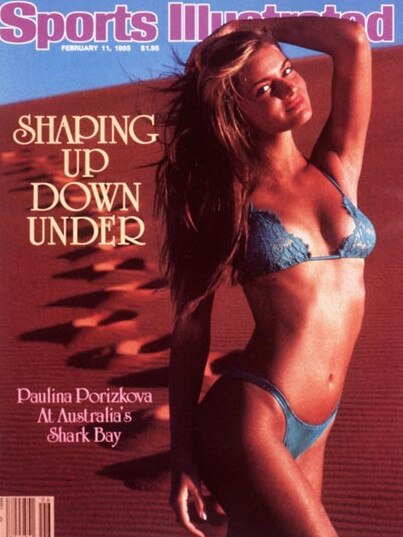

What is this party trick of which the 56-year-old, two-time Sports Illustrated cover star is so proud? What new skill has the once highest paid model in the industry, named by Harper’s Bazaar in 1992 as one of America’s ten most beautiful women, added to her repertoire? “I am now completely invisible,” Porizkova explains. “I walk into a party, I try to flirt with guys and they will just walk away from me mid-sentence to pursue someone 20 years younger. I’m very single, I’m dressed up, I’ve made an effort – nothing.”

Some women say it kicks in at 40; others when they finally “let” themselves go grey. Virginia Woolf described the phenomenon in Mrs Dalloway in 1925, aged 43. In 2005, then 47-year-old Kate Bush summed it up in How to be Invisible with the lyrics “hem of anorak / stem of wallflower / hair of doormat”. The actresses whose roles dry up, the widows left off guest lists. Bar presence, network, social interactions diminished. The female invisibility cloak falls heaviest on those most used to being looked at as well as (or instead of) listened to, and the time before it smothers you speeds up with every child you have.

“People between 50 and 80 report feeling ten years younger than their chronological age,” says Nancy Pachana, 56, professor of psychology at the University of Queensland and co-director of its Ageing Mind Initiative. “So you might easily feel 40, but it’s as though you no longer exist.”

“It’s a slow fade,” agrees Porizkova. “Like the boiled frog, you don’t know until [you’re gone]. It was around the same time my marriage fell apart: my husband was no longer interested in me and, as I started looking around, I realised I was invisible to the population at large. It made me feel really terrible about myself. The only way to gain visibility in our society is to look younger. If you look your age, nobody will listen to you, and if you want to be heard you can’t look your age.”

That’s why she has taken to Instagram: on the internet, everyone can hear you scream. Even as Porizkova feels her presence diminishing in real life, she has, since her divorce, built up a base of almost 700,000 people who follow her one-woman resistance movement against going gently into that good night. They comment on her bikini shots, nudes (yes, nudes) and makeup-free selfies in their thousands – although not always kindly. There are those – mostly men, but not all – who tell her to keep house, and her clothes on, instead.

“I started posting the same kind of pictures that have been taken of me since I was 15,” she says. “I look good. I didn’t realise it would be shocking for a fiftysomething woman to pose in the same bikinis from 30 years ago that still fit. It’s OK to ogle somebody who could be your daughter but not mature women who know themselves and are most likely way better at sex?” This is why many of her single friends end up dating “much, much” younger men, she says; those men “want to learn”.

“Do I feel sexier? Oh my God, yes. But what I am not any more is feminine. I am not a fluttery, vulnerable creature. I am an active participant, an instigator. I know what I like and how I work. I like to have fun. I know what I’m doing.” She laughs. “That really makes them run away.”

Taking in the fine-featured, high-cheekboned, almost perfectly symmetrical face and sweep of long ash blonde hair in front of me on Zoom (we won’t be attending that party together any time soon, alas), I can’t believe I wouldn’t notice Porizkova. Perhaps the parties I go to have a lower threshold for beauty. Perhaps when you’re the widow of a rock star – Porizkova had two sons with her husband of 30 years, Ric Ocasek, of the Cars – and the recent ex of the screenwriter/director Aaron Sorkin, the circles one moves in are more rarefied. More mummified, certainly.

“I understand the impulse to tweak things to gain confidence because you are becoming invisible,” she continues, luminous skin crinkling ever so slightly into the habitual expressions that she is on record as never having had filled, jabbed or Botoxed away like so many of her peers. “But once you do that, you’re actually servicing exactly what you’re trying to oppose. We need to stand up and insist on not being invisible. I wish there were more women who left their marionette lines [which run down from the corners of the mouth] and forehead lines and crows’ feet. I wish there were more women who dared to age.”

You’d be forgiven at this point for thinking that bravery is all well and good when one has the bone structure for it. You might not feel like taking lessons on ageing from someone whose face once earned $6 million for a single Estée Lauder contract. Someone who is astonishingly beautiful. “I get this a lot,” Porizkova responds. “‘It’s easy to age when you look like you.’ OK, that’s fair. I was once celebrated for how I looked. But age is a great equaliser and we are all on the same trajectory – downhill! Whether you start higher up or not, we all decline. The fact is, I am as invisible as any other 56-year-old woman walking into a party.”

There are, at least, more women over 50 at the party than there used to be. In the past month, the Sex and the City reboot, And Just Like That…, put three of them on our screens at prime time: Sarah Jessica Parker and Kristin Davis are the same age as Porizkova; Cynthia Nixon is 55. The new season Saint Laurent campaign unveiled around the same time stars a 65-year-old Jerry Hall, still smouldering almost 50 years after her first appearance on the French label’s catwalk. January’s issue of British Vogue features on its cover the 57-year-old American model Kristen McMenamy, whose long silver hair and grungy-goth style have earned her a new fanbase among Gen Z. On the spring 2021 catwalks (mainly videos or films, thanks to the pandemic), there were 32 appearances by older models. A few more on our screens too: Harriet Walter (71) in Succession, Kristin Scott Thomas (61) in Fleabag, Frances McDormand (64) in Nomadland. “There are more older women in the public space,” agrees the psychotherapist and author Susie Orbach. 75 “That has become a prerequisite, where we used to be able to ignore them. But sex is still the sell – our voices are there but we’re still invisible physically.”

Porizkova has come up with her own hashtag – #betweenjloandbettywhite – for the under-served bracket she finds herself in (singer J.Lo is 52; Golden Girls star Betty White died last month at 99). “I want to have someone to look up to and I don’t find a whole lot,” she says.

Last month, she starred in the beauty brand Laura Geller’s latest ad. She appears on camera lounging by a pool in a string bikini, running an office in a tight pencil skirt, outstripping younger women at a step class. “Let’s just say it: I’m getting older,” she declares in the ad, before launching into a stream of affirmations: older is sexy, older is experienced, older is powerful. She finishes with a hair flick: “I’m the best I’ve ever been.”

Porizkova has been through plenty to get here. In 2018, she announced she had separated from Ric Ocasek. Then, after his death in 2019, it was revealed he had cut her entirely out of his will despite the couple having been on amicable terms until the end. “That was a real kick in the ass,” she says. On a recent celebrity podcast, Porizkova alleged Ocasek had been controlling of what she wore, what she did and where she went, and that she conformed so as not to “risk losing his love”.

“I was a trophy,” she tells me. “But I didn’t feel that way when I was with him. I felt so desired and loved. But when I lost his attention and his tenderness and his love, I realised it might not have been the healthiest of relationships. When you are a treasured possession, as opposed to a person who is loved, you don’t get to grow older. You have to stay the person they’re obsessed with.”

Despite this, she didn’t go down the surgery route. On a recent Instagram post about facelifts, she wrote: “Just because you can doesn’t mean you should.” Instead, Porizkova posts selfies from the treatment chair where she has non-invasive plasma pen sessions, tightening ultrasound therapy and hydra facials. She used to box, but hip arthritis means she no longer can. (“That makes me sound ancient,” she groans.) These days she concentrates on Pilates and professes to have abs for the first time. “Oh, I’m vain!” she admits. “I don’t look good under bright lights these days. In fact, light plays a very big part in my life now” – evidently, given she spends the first minute of our Zoom phoning her 28-year-old son, who is elsewhere in the house, to fetch a ring light that will throw a softening halo over her features while we chat. “I can’t do an interview without it.”

I know how she feels. Such apparatus became standard issue when we all had to work from home. More than that, the daily confrontation with our image led not only to the coining of the phrase “lockdown face” (drawn, dry, chapped, spotty) but also to a so-called “Zoom boom” in cosmetic procedures as soon as restrictions lifted.

“We are in a society set up for women who look like little girls,” Porizkova says. “That shouldn’t be OK with us. We need a collective movement to fight ageism, but it requires a bending of the sisterhood, which just hasn’t happened.” The academic Nancy Pachana believes the hold-up is because the cohort in charge of steering the zeitgeist, both corporate and cultural, hasn’t come to terms with its own inexorable – but not necessarily terrible – fate and doesn’t want to see the near-future reflected back in the media they consume. “People are most scared of ageing in their forties and fifties,” Pachana says. “Once they turn 60 and things don’t fall to pieces, most people find being older is pretty cool. But between 40 and 50, they have those fears, and those people tend to be in positions of influence.”

Yet, while many young women are starting cosmetic procedures ever earlier, there are others who – at the point in their lives when they decide whether to do it or not – are desperate to see women ahead of them ageing naturally. I am one of them. And rather than tuning out those in later life, many young people seem interested more generally in what they can learn from them: the youth vote turned out in the US and the UK for Bernie Sanders (80) and Jeremy Corbyn (72); the 87-year-old environmentalist Jane Goodall is popular among 19-year-old Greta Thunberg’s peers. When the late author Joan Didion appeared in fashion house Celine’s ad campaign in 2015, aged 80, sales of her books rose rapidly among millennials learning of her for the first time. Like children and grandparents, non-consecutive generations often have more in common.

As baby boomers age, they are tackling the stereotypes of what being old really is. Many of them were hippies, some of the first eco-warriors; the first rock stars; the first to experience the effects of LSD. They are stardust, they are golden – and they will not be wearing the same old Crimplene slacks of yore. “The best predictor of future behaviour is past behaviour,” says Nancy Pachana. “The stereotype is that you become more conservative with age, but if you were voting for the Greens at 30, you’ll be doing it at 80. If you really like sex, you still will at 100.”

Increasingly it is education and class, rather than age, that influences your outlook on life. Sociologists see a future where generations integrate far more than they do now, as older people work longer alongside younger colleagues and both bring different attributes to the table.

Right now, though, we’re still pushing the boulder up the hill, says Porizkova. “There’s been improvement in representation of everyone except older women, and it’s because more of us are not offended. Instead of things that promise to erase our faces, we should be buying products advertised by women like ourselves.”

Naturally, she’s open to offers – from those who can see her, that is.

© The Times