Paul Kelly’s How to Make Gravy makes leap from the songsheet to the screen

The film adaption of Paul Kelly’s How to Make Gravy is a story about angry young men and their mistakes. Hugo Weaving believes it’s a tale of the modern Australian male that must be told.

The days around Christmas and new year can feel like a fever dream. Come December, we’re searching the high shelves for the glass trifle bowl one moment and then – blink – the holidays are upon us. Tools are down. Rules are bent. We’re popping the champagne a little early, cracking open the jigsaw puzzles and leaving them unfinished on the table. Gradually, if we’re lucky enough, we’ll forget what day of the week it is.

For those who temper their festive cliches with a side of melancholia there’s a perfect soundtrack to this fever dream. It isn’t a song about sleigh bells or snowmen. It’s a song about hard times and homesickness. A bittersweet ballad about a man who can’t be there this Christmas, but he loves you all, he misses you, and he’s sorry. So very sorry. The song is, of course, Paul Kelly’s How To Make Gravy.

“Hello Dan, it’s Joe here, I hope you’re keeping well,” it begins.

“It’s the 21st of December, and now they’re ringing the last bells.”

Since the song was released in 1996, and became a classic, December 21 has come to be known colloquially as Gravy Day. That’s the day the song’s protagonist, Joe, pens his letter home from prison. “They say it’s gonna be a hundred degrees, even more maybe, but that won’t stop the roast,” Kelly sings, and immediately, wherever you are in the world, it’s Christmas Day in Australia: unbearably hot and the flies are buzzing but our ovens are cranking. Then the next lines tumble out and wretched Joe’s forlorn query:

Who’s gonna make the gravy now? I bet it won’t taste the same

Just add flour, salt, a little red wine

And don’t forget a dollop of tomato sauce for sweetness and that extra tang

And give my love to Angus and to Frank and Dolly,

Tell ’em all I’m sorry I screwed up this time

And look after Rita, I’ll be thinking of her early Christmas morning

When I’m standing in line

How to Make Gravy is written in the same tradition as that bleak 1988 Christmas classic Fairytale of New York by The Pogues, featuring Kirsty MacColl. It’s influence is writ large in Tim Minchin’s silly season ballad, White Wine in the Sun. In it you can hear the rhythm and intuition of Kelly’s hero, the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, as Gravy brings to bear the rawness of Kelly’s own life. The shaky ground on which he lived, for a time, of his drug addiction and relationship blow-ups. He wrote about it all in his 2010 memoir; also titled How to Make Gravy.

Across 28 studio albums and over 400 songs, spanning four decades, Kelly has variously invited us to reflect on the Dumb Things we’ve done and showed us that From Little Things Big Things Grow. How to Make Gravy has been streamed more than 45 million times on Spotify, and covered by artists as wide-ranging as the soulful Christine Anu, by fellow Aussie rock king James Reyne, folk four-piece All Our Exes Live in Texas and Tasmanian punk rock band Luca Brasi. It’s a song that is so ubiquitous and so well-loved that of course a bloke would turn to his filmmaker mate on Christmas Day and say: “Gee, How to Make Gravy would make for an incredible film”.

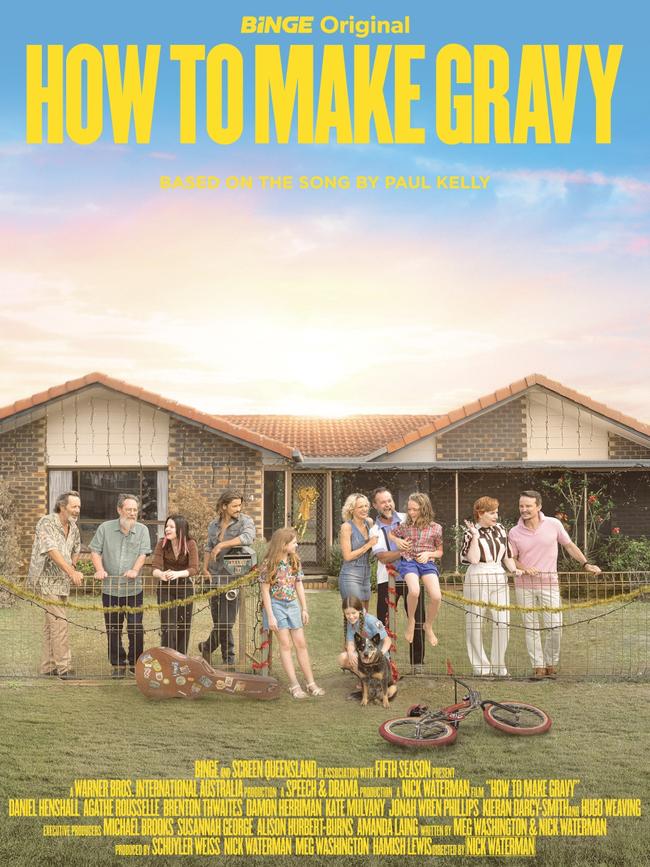

Next month, How to Make Gravy’s mythical characters will make the leap from the songsheet to the screen. The film adaptation, to be streamed on Foxtel and Binge, features Joe, Dan, Rita, Angus, Frank, Dolly, Mary and “the brothers driving down from Queensland” but stretched and “coloured in”.

The actor Daniel Henshall says: “There’s something in the way Paul writes a verse so simply, but every time you listen, it goes deeper into your consciousness”. Henshall, who will play Joe in the film, adds: “You don’t have to be someone who’s a lit major – you can be anyone from any walk of life, with any education, and it can affect you. He’s such a wonderful storyteller of Australian life. I think he understands what it’s like to be here better than most.”

Henshall is known for taking on what he describes as “gnarly roles” – he played serial killer John Bunting in Justin Kurzel’s grim Snowtown, and troubled artist Adam Cullen in Thomas M. Wright’s masterpiece, Acute Misfortune. But when we meet in a photographic studio in Sydney for this magazine’s cover shoot he’s acting the goofball to get his colleagues, who aren’t actors, to loosen up for the camera. Director Nick Waterman and his partner, the Aria-award winning singer/songwriter Meg Washington, wrote the screenplay for the film and created a backstory for Joe (now with the surname of Morris), which among other things explains why he ended up behind bars that Christmas.

Playing Joe is, Henshall says, one of the “roles of his career”. His unguarded portrayal of the traumatised protagonist anchors the film, which is as sentimental a story as you’d expect at Christmas, infused with wry and wicked Aussie humour.

The notion that Christmas is not an idyllic, prawn-shelling, champagne-popping time of year for all families underpins Kelly’s poem-song. When I ask him what he thought was behind its enduring appeal, he says:

“A lot of people have strong feelings about Christmas. Some love it, some hate it, many love and hate it both. Even those who love it would say that it’s also a stressful time … and even the most loving families have hidden fissures.”

It’s a theme Waterman and Washington’s film picks up and runs with. Their origin story takes up from a year before Joe pens the letter that would become Kelly’s song. The set-up is as follows: the Morris family are attending their first Christmas bash since losing the family matriarch. The fissures are not hidden, they’re widening and Joe is feeling the grief most keenly. The family home is a brown brick bungalow that could be on the NSW Central Coast or in an outer suburb of Perth. (Shooting actually took place in Jacob’s Well, halfway between Brisbane and the Gold Coast; when writing the screenplay, Waterman and Washington came up with the concept of “Aussie Gotham” to conjure a look and feel that was uniquely Australian but an unspecific time and place.)

Outside, children walk the streets eating icy poles; the trampoline has no safety net; no one is on an iPhone; the bathroom and kitchen appear transplanted from the 1970s. It could be the 1990s, when the song was written, or it could be today.

The tension builds. Kate Mulvany plays Stella “flying in from the coast” and Damon Herriman is her objectionable husband, Roger. (Together, they steal all their scenes). Brenton Thwaites rolls in as Dan, an avoidant muso brother, and Mary materialises as Dan’s adult daughter, played by Eloise Rothfield – she’s in the back of the car with her new boyfriend. Before they get out he nervously sprays just “a little too much cologne”.

The French actor Agathe Rouselle gives a brilliant performance as Rita, Joe’s wife. She is loving and supportive but Joe – shut down, resentful, and tormented – is having none of it.

In this powder keg of a situation, Joe, beset with anger, commits the act of spontaneous violence that lands him in jail.

“We followed what the song wanted,” Waterman says of the approach to transporting the song to the screen. Gravy is his feature film debut (he has previously directed three short films and several music videos) and we are talking over a video call from the Brisbane home he shares with Washington and their six-year-old son, Amos. The couple sit side-by-side, and finish each other’s sentences; behind them I can see Amos’s drawings stuck to the wall.

“We wanted to be able to justify our choices by using the song’s logic,” Waterman continues. “We know that Joe and Dan are brothers, and that Rita is his wife. He says ‘Give my love to …’ and he says Angus’s name first, and then pauses. If I were in prison, and I were writing a letter to someone, the people that I would be naming first are my children.”

When we meet in Sydney several weeks later, Amos comes along, and the family make a tight trio, each deeply attuned to the other’s needs. Henshall is there too, tossing Amos over his shoulder with the familiarity of someone who is part of the family, and the ease of a dad who has two young boys himself.

In Waterman and Washington’s story things don’t get any better for Joe once he goes inside. His temper manifests in bursts of physical rage, threatening to thwart what he wants most – to be home by July, still seven months of good behaviour away.

As Henshall puts it, “He doesn’t help himself while he’s in there … I think he’s repeating a past untapped trauma with his inability to regulate emotion, which is very common in people who have suffered abuse or trauma in their life”.

Help comes in the form of veteran prisoner Noel, played by Hugo Weaving. He offers Joe a safe place working in the prison kitchen, with one condition – he has to attend a men’s group. Noel, a new character, was written for the film after Washington and Waterman started working with a psychiatrist to “break down the symbology in the lyrics to their deepest Freudian and psychological essence,” Washington says.

They emerged with a script that explores confronting male vulnerability as a means of breaking a cycle of violence and intergenerational trauma.

It’s childhood, specifically boyhood, that is at the heart of the film, with Joe’s 10-year-old son, Angus, played by Jonah Wren Phillips, stepping forward as the film’s narrator – “telling the story mainly through the eyes of Joe’s son, Angus, was a brilliant move,” remarks Kelly, who gave his blessing to the couple’s detailed pitch.

It’s during our second interview, after speaking at length, that Waterman shares with me the painful memory of losing his mother when he was five years old. “Amos was approaching the age that I was when I lost my mum,” he says. “That was something that I drew upon for the character, and a way that we found a connection to Joe and Angus. I felt like there was something that Joe needed to let go of, and I felt like that was something that I needed to let go of too.”

Hugo Weaving is sitting in his book-lined study eating a chocolate chip cookie telling me that he is sick of Australian male characters that have “no light at the end of the tunnel”.

He describes the character of Noel as “a quintessentially Australian male character without the bullshit that I think is often embedded in those men.” The audience learns everything they need to know about Noel the first time he enters the frame. “That’s a relief,” a prison guard says, as his burly but comforting presence diffuses a tense situation.

Noel’s fatherly mien could not be more different from the ruthless Frank Harkness character Weaving plays in the latest season of the British spy thriller, Slow Horses. But if anyone can toggle between villainous and avuncular, it’s Hugo Weaving. “I think we all want Hugo to be our dad a little bit,” Waterman says. “I know I do.”

As the boss of the prison kitchen, Noel becomes something of a father figure for Joe and the other inmates (his character is aptly named; it’s a Christmas film, after all). I write down the words “trauma shaman” after a particularly moving scene where Noel leads a men’s group.

Weaving says: “When we think about the traditional role of the man in society, we think of someone who should be loving, caring, providing, capable … but the 1950s American ideal of manhood – the ‘I can fix the car, I can fix the washing machine, I can make money at work and bring it back then read my kids bedtime stories, and not get upset about anything, because I’m a man’ – that can be an impossible place to be.”

I venture that the film might come at a time when there is less sympathy for some men’s stories. There is, instead, an expectation that white men of a certain age, and social class – such as Joe – should “check their privilege” before talking about their “first world problems”.

Unlike the film’s writers, Weaving is old enough to remember the social climate in which the song was written. Of the many hundreds, if not thousands, of books in his study I notice the blue spine of Kelly’s 2010 autobiography high on a shelf, wedged between Patrick White and Tim Winton

I ask him to reflect on how Kelly’s characters might be perceived differently today.

“Paul would have grown up and come out of a slightly earlier age when I think in many ways, we were … more liberated,” Weaving says.

“It feels like we’re in a more conservative, more restricted, more competitive, more selfish, more self-centred world, and politically in a more censoring place than we were when he wrote the song, which is interesting.

“And I think we’ve shifted a lot in terms of male politics. In one way, the idea of making a film about white men or male issues … sure, we’ve been there. But this is actually a film about family. And if the man doesn’t sort out his place within himself in society, and within the family, the family is never going to function properly. If a man can’t say sorry, if a man can’t be weak, if a man can’t be complex and express complex emotions, the family will suffer. And I think that’s what’s great about the film. It’s actually not purely about blokes.”

Kelly tells The Weekend Australian Magazine that the film “teased things out of the song that I hadn’t been aware of – it explores the link between violence and humiliation and shows that accepting vulnerability and being open to the hand of friendship and the forgiving arms of love is the true source of strength”.

He’s more nonchalant about what he set out to do with the song, which he wrote without too much idea of the backstories. And yet it’s fair to say the heroes in Kelly’s songs are often men who mess up. They also redeem themselves. In the film’s opening scenes, Joe, who has recently lost his job and is sinking beers, wears a white shirt with a blue collar. Kelly has said that Joe is the same character in his songs Love Never Runs on Time and again in To Her Door. The one who “started up his drinking, then they started fighting; he took it pretty badly, she took both the kids”.

Henshall, who was all of 14 when How to Make Gravy was released, has a different generation’s perspective. He wonders if there might have been “more excuses for bad behaviour back then. In the past, the attitude towards those ‘good old knockabout boys’ was that ‘they’ve got a good heart, but they punch people’. Or ‘poor mate he’s got a bit on his shoulders’. Society is doing a much better job of not turning away from that now.”

But Henshall also worries about the suicide rate of men in Australia. “There’s obviously something wrong. The beauty in the film that we try to do within the four walls of Paul’s brilliant song, and with the healing art of music and community, is to give space to that and to show how it may change.

“There are so many negative outcomes when men are not able to express what’s going on for them without using violence, whether it be verbally, physically, or emotionally. We need to teach our boys that they’re allowed to tell us how they’re feeling and not to resort to internalisation, which could lead them to suppress until they explode. What we tried to do in the film is to show how it can change.”

It’s a lofty goal, but Henshall is the actor for the gig. As the character softens, and embraces pain and vulnerability, so too does Henshall’s entire demeanour – at times it looks like a different actor has taken over the role. The tenderness between Henshall and Weaving as Joe allows himself to heal is enough to make anyone want a hug from Hugo Weaving.

Waterman says Kelly’s line “Won’t you kiss my kids on Christmas Day, please don’t let ’em cry for me” triggered something for him.

“I was always told not to cry,” he says. After sharing the loss of his mother at such a young age, this is especially saddening. Henshall tells me that he cries when he listens to Kelly’s songs. I cry when I watch the film. Weaving says the music Washington wrote for the soundtrack brought him to tears. Tears flow in the interviews for this film and, according to Waterman, “a lot of tears went into the script”. At one point in the film, Rita visits Joe in jail and tells him to “stop crying with his fists”.

“We knew early on that what we wanted to say through the film is it’s OK for men to cry.”

Kelly’s ballad was borne out of a request from John Farnham’s guitarist and backing singer Lindsay Fields for his annual Christmas charity record. Kelly wanted to cover Christmas Must Be Tonight by The Band, but somebody else had chosen it, so he agreed to write his own. The sparkling lyrics that move a nation every holiday season came about, he says, “from practical reasons … from trying to solve a problem; puzzle tinkering without any big, overarching idea”.

“I remember sitting in my back shed thinking, ‘Does the world really need another Christmas song? And how the hell am I going to write one?’ ”

Then the poet in him kicked in. “The best way to summon a strong feeling of Christmas was to write from the point of view of someone who can’t come home,” he says. “My next thought was, ‘Well, why can’t they come home?’ And then straight away the next thought came, like a key turning in a lock, ‘Oh, they can’t be there because they’re in prison!’ ” After that, Kelly says, he doesn’t “remember much more about the writing of it at all”.

It was after Kelly finished writing the song that he listened to Darlene Love’s version of White Christmas, from the record he plays loud every Christmas morning – A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector.

“It was then I realised the composer Irving Berlin had done the same thing many, many years ago. The power of that song comes from the narrator not being there. Nothing new under the sun!”

“He’s such a great balladeer,” says Weaving. “For me he felt like the quintessential Australian singer songwriter, with a tough, personal, inner city life, but speaks to the country at large. There was something about him that kept on keeping on as well. He could have died very easily, but weathered the storm of it. So there’s something in him as a person, in what he’s seen, where he’s been and done that. He writes with honesty and a kind of love and generosity for the truth about human beings, and about love, family and people.”

Kelly confirms the atmosphere is based loosely on his own family Christmas which features a big clan – “a kind of happy chaos”. And the gravy recipe comes directly from his first father-in- law.

Ah, the gravy. Much has been made of the controversial “secret ingredient”. “And don’t forget a dollop of tomato sauce for sweetness and that extra tang”. Foodies over the years have argued that tomato sauce has no place in gravy. Henshall, a keen cook, says he makes a good one, and the secret ingredient comes from whichever herbs have been cooking alongside the roast, infusing the pan juices. Washington says she’s partial “to a jus”. In the film, the gravy is an allegory for change. Joe has inherited the recipe – and much more – from his father, but we can change what we choose to pass on to our children.

In turning the world of the song to film, Waterman and Washington went deep into the “Kellyverse”. The family’s surname, Morris, is an alternative pronunciation of Maurice, Kelly’s middle name. The blue-collar shirt Joe wears in the opening sequence is a recreation of one that Kelly wore in a famous press image. Washington has a cameo as the Morris family neighbour; her name is Kelly. And there are more references, or what the couple calls Easter eggs, littered throughout the film.

“In the dreamscape of this movie, we are inside a song,” Washington says. “I wanted to have the sense that the movie was like plunging your head into the lake of the song, and you see this different world under the water.”

And while the film is not a musical, Washington says it’s also not “not a musical”. When we talk about the cluster of Australian musicians in the film – Adam Briggs, Brendan Maclean, Dallas Woods, and Patience Hodgson each peppered throughout the prison — Washington’s thoughts echo my earlier feelings about Christmas. “I wanted it to be an Australian film and music fever dream,” she says. Record producer Sam Dixon composed the original score, and Washington wrote two new songs for the soundtrack.

It’s a film that manages to be many things at once: it’s a family film that also places itself within the prison film genre. There are deep psychological themes but there is artfully positioned levity. “It’s delightful, and it’s very moving but it’s not a fluffy feel-good film,” Weaving says. “It’s a film that says, ‘This is who we are. This is our country.’ ”

And, essentially, it captures the nostalgia for a traditional Australian, Paul Kelly-infused Christmas. In the song, we never do find out who makes the gravy. In the film, which celebrates the redemption of almost all of its male characters (yes, even Roger), the lyrics are interpreted literally – “I’ll be making plenty,” Joe writes. “I’m gonna pay ’em all back”.

How To Make Gravy is available to stream

on Binge from Sunday, December 1 and available on Hubbl.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout