Patience, chance, and ‘rat-hole miners’: how Arnold Dix pulled off Indian tunnel rescue

In a single moment, 41 underground workers became trapped behind an unimaginably huge pile of debris. Arnold Dix hatched an audacious plan to set them free.

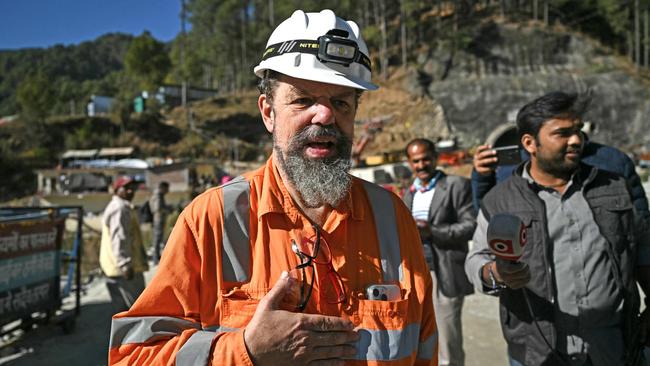

The name Arnold Dix will mean nothing to most people, given I have spent the past few decades of my professional life existing largely in the shadows. That’s how I like it: come in, get the job done, and go home again. No fanfare. Minimal fuss. Everyone is happy.

My mum taught me when I was a boy: “Do whatever you want, but just give it a good crack.” Those values are why I have given so many things a crack. To many I have encountered in life, I am a lawyer and barrister, working in top-tier law firms. Among an entirely different group of people I am a scientist and geologist who spends a lot of time underground, sometimes doing things I am unable to talk about because they are highly confidential, and at other times dealing with death and destruction on a scale no one should ever have to see. I’m also a visiting university professor in engineering infrastructure at Tokyo City University, and president of the International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association (ITA), which boasts about 150,000 members in 81 countries. It’s mission is to promote advances in the planning, design, construction and safety of tunnels worldwide. I grow sunflowers. For a small number of people, I was briefly a trainee hairdresser, an apprentice welder, a contract pest controller, and a truck driver for a local nursery. At various points in my life I have been described as an enigma, chaotic and a little bit nuts. Some call me a nerd. Someone once said I was the embodiment of one big, never-ending midlife crisis, such is my tendency to pick up a new hobby, or a new career, and run hard with it.

But in late 2023, everything changed. My approach – my entire life, if I am being honest – was upended by a catastrophic event on the other side of the world. The scale of the situation and the bizarre set of coincidences that saw me wind up in a remote part of India, high in the Himalayas, trying to make the impossible a reality, demanded that I no longer be anonymous and step forward into the public eye.

At 5.30am on November 12, 2023, a major collapse occurred 250m inside the entrance to the Silkyara Bend-Barkot tunnel project, trapping 41 workers inside. In the months prior, work had proceeded at pace on digging the tunnel, part of an ambitious highway initiative to connect four holy Hindu pilgrimage spots in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand.

Building a tunnel is always a challenge. It requires careful engineering, patience and a healthy budget. But here, the arduous environmental conditions the workers had been navigating each day added an extra layer of complexity. I can’t think of a more challenging part of the world to build a tunnel. Uttarakhand is home to soaring, jagged Himalayan peaks and spectacular, ancient glaciers. It is incredibly remote, and bitterly cold in the winter months. The beauty of the Himalayas masks the stark truth that given the chance – and without warning – the mountains will try to kill you. And it won’t take much.

It’s also here that you’ll find some of the holiest sites for Hindus. Each year, many travel the Chota Char Dham pilgrimage circuit to pray, make offerings and give thanks. They may take in all four sites – Gangotri, Yamunotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath – but getting around is not as simple as jumping in a car for a road trip. The few roads and paths that exist between these pilgrimage spots are treacherous. You regularly see the wreckage of cars, buses and trucks that have gone off the road and plunged into the valleys far below. Just a month before the tunnel collapse, a bus carrying a load of pilgrims was involved in a horrible accident that killed 39 people.

The idea was that the construction of a highway – and the Silkyara Bend-Barkot tunnel – would make it easier and safer for pilgrims to get around. Unfortunately, the area around the tunnel is a hotbed of natural disasters. It experiences just about everything Mother Nature can possibly throw at it, from floods to avalanches, mudflows and earthquakes. It’s also extremely geologically active, so tunnelling there is a risky business. It’s especially vulnerable to landslides, which is what went wrong on this occasion.

In a single moment, a group of workers became trapped behind an unimaginably huge pile of debris inside a dark, damp tunnel. The subterranean landslide created a cavernous void, 40m-high and 100m-wide. And it was growing, hour by hour, often in small increments but sometimes with sharp ferocity, as the earth kept rumbling in fury.

The Uttarakhand government quickly launched a rescue operation. Initially, hope of finding survivors was low – when a tunnel caves in, it’s usually a case of retrieving bodies – but it turned out that all those stuck on the other side of a thick wall of rock had survived; the rock fall had separated them from the entrance and created a kind of tomb. But one small misstep in the efforts to reach them, and all 41 of the trapped men would die.

As president of the ITA, I was notified of the collapse within hours. I sent out an alert to the key technical members and began assembling a team who could be called on if needed. Experts from across the globe began sharing knowledge and advice with me, which I relayed to the Indian specialists.

Usually, these types of disasters do not end well. I have seen the aftermath of tunnel failure plenty of times in my career. I had never rescued anyone alive before. For decades, my work has involved seeking lessons from the dead.

By day four of the rescue mission, I was on the phone with the secretary to the Indian prime minister, who asked me to explain my thoughts. He wanted me to be candid about how challenging the mission was likely to be. At the end of the call, he asked me if I would come to the site to pitch in. And if I could come as fast as possible. There was no job description and no contract – my help would be voluntary – but the mission was clear. Join the team and help in any way I can. I promised I would.

When building a tunnel, you can’t simplytake an enormous drill bit and start cutting. Once you’ve penetrated a mountain, the top and sides of the tunnel are subjected to extreme force. It’s hard to describe just how intense that pressure is. Everything above and on either side of that sudden new void is pushing inwards in a bid to refill the hole you have just dug. So tunnellers “trick” the mountain, by using complex physics to distribute the load around the new hole in such a way that it does not cave in.

When you enter the remnants of a tunnel after a collapse, you notice something stark. What should be a perfect semicircle or semi-oval – the sign of perfectly distributed pressure – looks like someone has taken to it with a crowbar. You notice the top is sagging and the sides are warped. We call this convergence. Convergence is a sure sign that the mountain is about to reclaim the piece of itself that humans have clawed away. The mountain has cottoned on to what humans are trying to do, and it is pissed off about it. This is exactly what I saw the first time I went inside the Silkyara Bend-Barkot tunnel. That mountain was about as angry as any I’ve ever seen in my three-decade-plus career working underground.

Venturing for the first time into the Silkyara Bend-Barkot tunnel was overwhelming. The first thing I noticed were the scars of 21 prior severe collapses inside. That was not good. Had there been just one or two, I could understand why work might have proceeded. But 21? It was incomprehensible to me why the tunnel had not been shut down until the situation settled. Outside, I ran my hands over the rock on the top of the mountain. It was so brittle that my gentle touch was enough to make it break up.

The signs of multiple previous collapses, and this horrible rock, were very worrying. I went to a meeting with the senior officials leading the rescue at the end of my first day on site. I tried to explain, politely and diplomatically, that the situation was – pardon my French – truly f..ked. “We can’t rush. The whole thing is going to collapse. There’s no stability here on our rescue side,” I explained. The officials sitting around that table asked me to assist them in getting these men out and home safely to their loved ones. “What are our chances?” I was asked.

In that moment, I just felt that we could do it. I felt deep in my bones that we would do it. We’d get these men out. The moment I walked back outside, a horde of reporters approached me. I was a foreigner who had just swept in on a helicopter, so they assumed I must know something. So I gave them an answer. “41 men alive, no one else hurt, all home by Christmas.”

The only way we stood a chance was if we softly approached the rescue; we had to carefully burrow our way to the trapped men. Within my first few days on site we got a thin pipe through the rubble and into the opening where the men were trapped, which meant we could use an endoscope to look inside. A small group of us watched the vision from the endoscope. It was chilling. It showed that the tunnel was essentially being torn apart. Bits of its reinforcements were hanging down. A lot of water was dripping from above and weeping from the walls. It was my absolute worst nightmare.

As the operation progressed, everything began to go wrong. The first auger used to try to dig through the rubble became stuck and would not budge. A second, more powerful auger was then brought in. We were carefully drilling in from our end, at the tunnel entrance, but discussing other possible options too – including drilling down from the top of the mountain (which would mean delicately cutting through 89m of rock), and coming in from the other side, through a longer but possibly more stable section of rock stretching 450m long.

For the moment, everyone was OK. The men were getting food, water, medicine and oxygen. That was an admirable achievement. It meant we didn’t have to rush or take unnecessary risks; we could be calm and calculated in our approach. Yet each day brought fresh ground shifts, which, at best, sent small rocks falling from the top of the tunnel. At worst, loud cracking sounds bounced wildly off the walls, causing us all to drop what we were doing and run. Advanced measurement tools were giving us real-time data, which showed the mountain was continuously moving. Sometimes, it was relatively gentle; other times, the readings were enough to send a shiver down my spine. We lived with the constant risk that we could trigger another landslide or a catastrophic collapse.

Soon we had another team working on the vertical shaft from the top of the mountain, trying to dig a space big enough for a rescue capsule to fit into. Another smaller shaft, also coming from above, was being dug as a kind of exploratory tunnel. As well as giving us more insight into what was going on, we figured it could act as a backup to the pipe sending food, air and medicine to the trapped men, in case we had another collapse in the tunnel. A separate team was working on the other side of the collapse, but the more the earth shifted, the clearer it became that the whole thing was unstable.

The rest of the team had most faith in the plan for coming in from above. But the more I pondered it, the less comfortable I felt with this approach. I had seen just how brittle the rock above us was on my first day. I was also concerned about the possibility of concealed pockets of water within the rock. If we happened to pierce one it could inundate the tunnel below, drowning the trapped men.

Specialised drones deployed inside the collapsed area produced a digital drawing that provided a colour-coded overview of the stability of the rock. Red and pink meant run away. There was a lot of red and pink. The drone data showed us that the initial collapse on our side was still ongoing; it had never stopped, it had just slowed down. We also discovered that in the mountain above where the collapse occurred was a 40m-high hollow space. Just picture how unstable and dangerous that scenario was: all of that unsupported rock just waiting to come down. Down below, inside the tunnel, both sides of the rubble were extremely unstable.

The more the rescue mission stretched on, the more I felt we had to calm down and slow down. I had to gently steer the thinking towards a more considered approach. But the approach I had in mind would be painfully slow, and I could feel patience wearing thin.

The tried-and-tested tools to cut through the mountain had failed. We had rolled out the biggest and toughest machines possible. We had exhausted most of our options and torn through the equipment at our disposal. In the end, all we had left were our hands. History’s first tool, doing what a technologically advanced machine could not. We decided to use those humble human tools to scrape back rock and rubble bit by bit, 100mm at a time. With bare hands, we would excavate the last 10m.

A pipe about 80cm in diameter was drilled into the debris as far as we could get it. Two men would then crawl in with a trolley about 2m long. They would load rock and dirt into the trolley by hand. Then they would pull it back out on a rope by hand and empty it, before going back in. It was slow and painstaking work. But with each load we removed, the pipe could be pushed a little bit closer to where the men were trapped. Each time the trolley was pulled back with a load of rubble, it was a reminder of just how unstable the situation was. It was rock, but barely. The shards had begun to turn to dust just by being scraped up in a worker’s hands and thrown into the trolley.

I still have all my notes from the rescue. I sketched out the mechanics of the operationin a bright red notebook that I carried with me. It covers just three pages. That’s it – the solution in its entirety. It is a rudimentary sketch of our slow-and-steady approach to reaching the 41 men on the other side of the pile of rubble. But it is a reminder of the time a team of people, propelled by belief and determination, worked together to design and build a system that would save people’s lives.

In India, there’s a subset of underground workers known as “rat-hole miners”. They hand-dig tunnels, clear blocked sewerage pipes and excavate coal with their bare hands. It’s so dangerous that some parts of India forbid this type of mining. But some unscrupulous mining operators see rat-hole miners as a cost-effective workforce – they’re paid as little as $5 a day – and so the practice carries on in secret in many parts of India. In a society famed for its deeply entrenched social hierarchy, rat-hole miners are at the very bottom of the ladder. But now, after the events of late 2023, they are regarded by many as heroes. Twelve of these workers proved integral in the rescue operation. Without their dedication and bravery, I can’t imagine how things might have played out.

Inside the tunnel, forming the core of our rescue mission, these men very gently excavated rock by hand, which allowed us to push our pipe a little further forward every day. It was slow and painstaking, but it had to be. Our “go soft” approach was crucial if we were to avoid pissing off the mountain any further. Two men at a time crawled deep inside the 80cm-wide pipe, working in four-hour shifts. What they did took enormous courage.

When one of the rat-hole miners eventually broke through to the cavern where the men were trapped, I am told it was a scene of jubilation. One miner ran forward to embrace his rescuer in a warm hug. Others burst into tears. Their nightmare was finally over.

After 17 long and gruelling days, at around 8.50pm on November 28, 2023, the first of those 41 men crawled out of the metal pipe. The rescue crew erupted into cheers. That excited scene was repeated 40 more times until the very last trapped worker had emerged. We had done it. They were free.

It was the very best of humanity at work. It was a thing of beauty. “Christmas has come early,” I told one waiting reporter. Each of the workers were taken to hospital for assessment. Miraculously, all were in good health and high spirits. They were kept for observation but the remarkable reality was that everyone was fine. The rescue site and surrounding village broke out in celebration. India’s largest-ever rescue operation had been a success. The impossible was made possible. The scenes were fittingly festive. Or at least, that is what I have been told. I quietly slunk away the first moment I could, disappearing into the shadows.

Post-script: Following a major investigation into the tunnel collapse, the Indian Ministry of Road Transport and Highways committed to overhauling its operating practices, as well as to audit 29 ongoing tunnel projects in the country. The Silkyara Bend-Barkot tunnel has since been stabilised and repair work is underway.

The Promise: How an Everyday Hero Made the Impossible Possible by Arnold Dix (Simon & Schuster) is out now