Outgoing NSW Police commissioner Mick Fuller has some parting shots

Outgoing NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller sets things straight, including a blunt assessment of the William Tyrrell investigation.

It had been a run-of-the-mill weekend in Sydney’s hotspots, up around Kings Cross, Oxford Street and on the fringes of the CBD. There’d been fights, overdoses, muggings – but the figures were trending down. It was a few weeks out from Christmas 2014 and Mick Fuller was at his desk early that Monday morning as his team tallied the coward punches and pinpointed where and how the scuffles had flared. The city’s controversial lockout laws had been in force since the beginning of the year, requiring last drinks by 3am. The tabloids and the shock jocks were patrolling the outcome. “At that time,” says Fuller, then the commander of Central Metropolitan Region, “alcohol-related crime was the only game in town.” As the weekend piss-up-appraisal was winding down, Danny Doherty, the region’s operations manager, rushed in to tell them a robbery was underway at Martin Place. Someone had walked into the Lindt Cafe with a firearm.

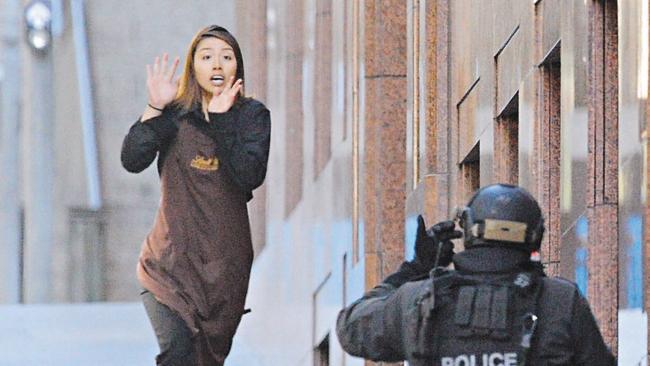

They all knew immediately this was no old-fashioned stick-up. Why Monday morning in crowded Martin Place? Fuller took his crew to a secure room and set up an incident management team. Within minutes it was confirmed hostages were being held. There were reports bombs had been planted at three locations in the city. Sydney, it appeared, was under terrorist attack as tens of thousands of commuters poured into the city.

“In those first two hours I made something like 63 decisions,” Fuller says. “Any one of those decisions, if you’d made one once in 10 years, it would be significant.” He put armed teams around the Lindt Cafe. He halted trains and ferries and closed roads. He evacuated parts of the CBD and ordered people to shelter beneath their desks. Three busy locations were swept for bombs. His team canvassed the possibility it was a co-ordinated attack and that other gunmen could be involved. Many hundreds of police flooded into the city – were his officers safe? Every order Fuller issued was vital. All the while, an agitated madman wandered around the cafe pointing a loaded pump-action shotgun at the terrified hostages. “Those first two hours were the most intense operational situation I’ve ever found myself in,” he says.

Fuller was in the hot seat for two and a half hours before being relieved by a specialist counter terrorism team. His cool handling of those hours, and his assured performance in the subsequent coronial inquiry, got him noticed. It nudged him into the orbit of political awareness. Others were in charge of the siege when hostages Tori Johnson and Katrina Dawson were killed but that didn’t exonerate Fuller of self-doubt. Does he ever wish he’d ordered one of his snipers to squeeze the trigger? He rephrases my question, puts it into police-speak. “In hindsight, do I think about… if I had given a direction to execute a deliberate action,” he says, “do I think about that? Yeah, regularly… lots of police, as will I, will carry that [burden] for the rest of our lives.”

Those troubling thoughts may cross his mind but there hasn’t been a lot of time to dwell on them. Ever since that dreadful morning in 2014 he’s lived life at a frenetic pace. When commissioner Andrew Scipione announced his retirement in 2017, Fuller threw his blue-chequered hat into the ring. His pitch was to take hundreds of police from administrative positions and put them back into operational roles. It was an attractive offer to the pollies: more police on the beat at no extra cost.

In the push for the top job he’s often described as the Steven Bradbury of the race as other candidates fell from favour. As one former insider told me, a senior police officer’s career “is a bit like an episode of Survivor – you can be the front runner and then something happens in your vicinity, which may have been completely out of your control, and you’re f..ked”. But the aces fell Fuller’s way, and the relatively unknown assistant commissioner skated around the pile-ups and into the command of Australia’s largest police force. He’s been speed skating ever since. Sydney is the epicentre of organised crime in Australia and so what happens in Sin City has a flow-on effect around the nation. Mick Fuller’s day job is to keep a cap on that crime, and to keep the citizens of his state safe. And now, after five years in the job, and at the age of just 53, he’s decided to retire while he’s still young enough to write another career chapter in the private sector. In March next year he will hand over to Karen Webb, NSW’s first female police commissioner.

One afternoon I hop into the back of Mick Fuller’s paddy wagon, a black Toyota Prado, which comes with a burly special constable as his chauffeur. We head to his favourite suburban pub, the Highfield at Caringbah in Sydney’s south. His usual brew is the workingman’s Tooheys New – but he’s partial to a glass of good red, or two. The pub is not far from where he grew up and where he still lives in the beachside Sutherland Shire. Every few months he ducks in to the Highfield for a beer and a punt with a bunch of blokes he’s known since school. Like his old neighbour in the Shire, Scott Morrison, Fuller likes to give the impression he’s the everyman. In reality, he’s now as comfortable mingling with corporate heavyweights and among the city’s movers, shakers and A-listers. He had a close working relationship with the former NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian. In the depths of the pandemic, when she was proposing a public sector wage freeze, she gifted him an $87,000 pay rise, making him one of Australia’s highest paid public servants on a package of $650,000 – a quarter of a million more than her own pay packet and $100,000 north of the PM’s. Berejiklian tells me he was worth it. His leadership, particularly throughout the pandemic, was “outstanding”, she says. “There were many, many days when things looked very dark… it was just very reassuring to have [Fuller’s] unqualified support.”

Fuller has made friends with influential journalists and editors, and radio kings Ben Fordham and Ray Hadley. He describes former News Ltd CEO John Hartigan as “a mentor”. He’s tight with Tony Shepherd, the chair of Venues NSW – which evolved from the old SCG Trust, Sydney’s most prestigious board. “In the past,” says Shepherd, “the police tended to be a bit more remote… Mick wanted to see us as a partner, somebody we could rely on who would look out for our interests.” The powerful Peter V’landys – chairman of the Australian Rugby League Commission and CEO of Racing NSW – describes Fuller as “a man of great ability who’s had experiences that you just can’t buy”. Fuller was instrumental in helping V’landys kickstart the NRL in the midst of the pandemic. “He was very good to us and supported us,” he says. Earlier this year, V’landys controversially offered Fuller a job on rugby league’s governing body, the ARL Commission, which came with a $75,000 stipend. The deal was scuttled when even Gladys Berejiklian could spot the potential conflict.

Fuller appears to have conquered every challenge that’s been hurled at him and has fashioned NSW Police into a modern organisation that’s been able to pivot from drug busts to bushfires to hastily building and administering a quarantine system. Is he the very model of a modern police commissioner? Or has he, as one senior Labor figure says, “blurred the lines between government, business and media in a way that has compromised the independence of the police”?

Now, on his way out the door, he’s waded into the murky waters of the William Tyrrell investigation. The disappearance of the three-year-old in 2014, a few months before the Lindt Cafe siege, sparked one of Australia’s largest-ever homicide investigations. This was a once-in-a-generation crime. For five of the seven years the case has remained unsolved, Fuller has been the officer ultimately in charge. When news of a possible breakthrough came in recent weeks, Fuller gave an exclusive radio interview to his mate Ben Fordham on Sydney’s 2GB and dropped a bombshell. “I brought a new team on board under Detective Inspector Dave Laidlaw,” he said of his appointment of Laidlaw two years ago. Laidlaw, Fuller said, had “inherited a bit of a mess” and that “time had been wasted” by the previous investigators, in pursuing “persons of interest that were clearly not”. It was an extraordinary attack on the two previous lead detectives, Hans Rupp and Gary Jubelin. Fuller has not been content to tiptoe out the door and into retirement.

Mick Fuller has a trait that is highly unusual amongseniorpolice.He’s able to say, “We got it wrong.” He’d just sat down in the commissioner’s chair when the coroner handed down the findings of the Lindt Cafe siege inquest. Throughout the inquest a number of senior police defended their decision to negotiate with the hostage-taker, following the containment and negotiation strategy that had been in place for years; police waited 16 hours, and only went in when the gunman fired his first shot. The coroner concluded that police had made a number of tactical errors. Fuller agreed. “We certainly should have gone in earlier,” he said after the report was delivered. “We needed to have gone in when there was a sense of control.”

“If Skip [commissioner Andrew Scipione] had still been in the chair he would have fought tooth and nail to not make any concessions,” a former senior insider says. “Whereas Mick said, ‘Nope, we got it wrong and we need to learn from that’.” It allowed the organisation to move on. But it was also devastating for the officers in charge and on duty when the two hostages were killed, to hear their boss say they’d got it wrong. “I can tell you that the guys in charge [when the two victims were killed] – they were scarred – they were on the Lindt diet, they all lost two stone and a lot of them have left the organisation,” says this former insider.

Saying “sorry”, or “we were wrong”, has been a trait of Fuller’s since he came into the job. He apologised to the original Sydney Mardi Gras marchers, the ’78ers, who were assaulted, jailed and persecuted by police. He apologised to the family of Scott Johnson, who was murdered in a gay-hate crime in 1988. He apologised to the family of Jack and Jennifer Edwards, who were shot dead by their abusive father, John. Their distraught mother Olga killed herself in grief. “The systems, processes and people let Jack, Jennifer and Olga Edwards down, for that I am sorry,” Fuller said. “We have to take responsibility for their deaths.”

Eventually, he said sorry too for the police practice of strip-searching kids at music festivals. On this issue, his apology may have come too late. In 2019 he defended the practice. Youths, he said, “need to have respect and a little bit of fear for law enforcement”. Then came a damning report from the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission that found police lacked training and had little understanding of legal issues around strip searches. Fuller has since reviewed the way the searches are conducted and has initiated various safeguards. “I met with some parents whose kids had been strip-searched,” he says now. “And I came out and said, ‘We need to do better’.” It could prove costly as a class action was recently launched on behalf of young people claiming to have been unlawfully strip-searched.

His wife Andrea, a former police prosecutor, tells me Fuller doesn’t “operate with hidden agendas” and, if you ask him, he’ll tell you directly what he is thinking about any particular issue. “His primary objective as a leader is to be effective, and to be effective you have to earn the trust of the community… he’s open to being corrected and to seeing things from other people’s perspective.”

Fuller says he lived through the humiliation of the Royal Commission into the NSW Police in the mid-’90s, in which the deeds of crooked cops were paraded on the nightly news. “I don’t say sorry lightly,” he says. “But the reality is that the buck stops with the boss and these were cases I felt compelled to call out.” It’s important, he says, because if you lose the trust of the community you’re in trouble. “And we lost the trust of the community after the Royal Commission and it took 20 years to rebuild that. People want to hear the truth from commissioners. They don’t want political speak. They don’t want to hear people mincing words.”

The flip-side is that some cops think he abandoned them when the going got tough. And some claim Fuller’s order for heavy-handed enforcement during western Sydney’s prolonged Covid lockdown this year caused him to lose faith with a community police have worked hard to win over. State MP Jihad Dib says there seemed to be one law for the eastern suburbs and another for the migrant-rich west. Fuller says his wife, Andrea, is a migrant from South America who grew up in the southwest suburb of Fairfield; he has friends and family who live there, so he was well aware of the concerns. “But the numbers out there were enormous at the time… and like it or lump it, we stopped the spread of the virus across the state.”

One of the many serving and former police I contact to get an assessment of Fuller’s reign is a grizzled old detective who still enjoys locking up crooks and helping victims. He’s a man who’s never been prone to flattery, and so I am surprised by his assessment. “He understands the street cops. He’s come up through the operational ranks… he handled the Lindt Cafe [siege] well – we’d never had anything like that in the history of the cops before – and he did well with the pandemic.” Fuller, this detective says, has got police thinking about new ways of doing things. “You don’t want cops sitting around saying, ‘That’s how we did it in the good old days’,” he says. “Let me tell you, I was there, the good old days were f..ked.”

Another officer, a country commander, says regional NSW has never been so well resourced. The additional resources that have flowed to the bush allowed him to tackle crime in an intelligent and targeted way. “For the first time we felt like we were on the map,” he says. “He [Fuller] listened and he realised it’s not just about Sydney, Newcastle, Wollongong…”

Fuller has been thrust into momentous events but luck and circumstance have also been on his side. Behind that perpetually terse face – the scowl of a bouncer, steadfastly declining entry – there’s a rainbow shining out the back of his hat. For the past two decades traditional crimes in Australia as well as many other developed countries have plummeted. The murder rate in NSW has halved, robberies have fallen by more than 80 per cent, the number of motor vehicles stolen and houses broken into has nosedived. It’s part of a broader trend; crooks can’t be bothered breaking into your house – your second-hand television or laptop are worth virtually nothing. Advances in technology have allowed police to link perpetrators to a crime in a way they never could before. “It is very hard to become a serial offender now,” says Fuller, due to electronic footprints, advances in DNA tracing and a proliferation of CCTV.

The crimes to rise under his watch are sexual assaults, up 8.5 per cent, and domestic violence, up 3.3 per cent. “The two big issues for us are adult sexual assault and child sexual assault,” he says. “These are big issues for society.” A decade ago we “ripped the Band-Aid off” domestic violence, he says, and something similar needs to happen now with sexual assaults. “They are devastating, terrible crimes and we need to focus on them, but they are difficult to prevent.” He backed new affirmative sexual consent laws that have just passed the NSW Parliament, though his idea for a “consent app” to tackle sexual assault didn’t fly.

And so not only has he had less crime to deal with overall, he’s had more police than any previous commissioner. “I was the first police commissioner in history allowed to move troops to where I thought they were needed,” Fuller says. “I was given an edict by the government in 2017 to make the service more agile.” He spent his first 18 months in the job rearranging his chess pieces. And then he was gifted a spare queen and a bunch of pawns. Late in 2018, Gladys Berejiklian announced an additional 1500 police – the largest increase in police numbers in 30 years.

Still, Fuller has his detractors. “Frankly, we were all a bit gobsmacked when he got the job,” says a former senior officer, voicing the sentiments of a minority, before launching into a long and scurrilous character assessment. I was unable to substantiate the main grievances. But this former officer did articulate a common complaint about Fuller, that he became too close to Berejiklian and protected her ministers, especially the police minister, David Elliott. A similar allegation is made by a senior Labor figure. “I really do think that he compromised the independence of the force. He formed a very close relationship with the Berejiklian government, he was closer than any previous commissioner had ever been… as commissioner you should not ever feel obligated to protect the Premier or a minister.”

It’s a difficult waltz – the commissioner needs the confidence of the premier to do the job. Radio presenter Ben Fordham says the job is inherently political. “I think you are kidding yourself if you think being police commissioner doesn’t involve politics,” he says. “You are linked at the hip to the premier who appointed you.”

Fuller is aware of these criticisms and at one point, when I ask him about Berejiklian, he says: “If I say anything nice about her then everyone will say I was too close to her.” Later he says it was because of this good relationship with Berejiklian that he was able to argue for more resources. Fuller denies he did the conservative government any favours and others point out that during Fuller’s time, police launched criminal investigations against three Coalition MPs. “In the police commissioner’s job,” Fuller tells me, “you try not to make it political, but you seem to become engaged in a lot of things that are political.”

The other common complaint about Fuller is that he has promoted his mates. “I actually think he hasn’t done a bad job in a lot of areas,” says a recently retired senior detective. “The Covid response has been outstanding… but he’s promoted a lot of his mates and some of them just shouldn’t be there.” This, again, is hard to prove or disprove. Everyone has their gripes, but the response from the many police I canvassed was generally positive. Tony King, the head of the powerful NSW police union, says Fuller has “steered a steady course” during some of the “most trying times we have ever seen”.

With that fixed grimace of his, Fuller would make a good poker player. Ben Fordham says he’s been with the commissioner in various settings and Fuller never holds court. “He’ll give you an honest answer if you ask, but mostly he holds his cards pretty close.” Fuller’s wife Andrea tells me that not long after he was appointed commissioner they took their two now teenage girls to Hawaii. They were there when a public alert said a ballistic missile had been launched and people needed to take shelter: This is not a drill, the warning blared. “I was sideways packing bags and kids and passports and trying to run to the bunker,” Andrea says. “Mick, in the face of what I thought was our lives coming to an end, didn’t even flinch and I remember thinking at that point there is nothing that will shake him… I was slightly annoyed that he wasn’t more panicked and concerned that my life and our kids’ lives were about to come to an end.”

Fuller is an avid cook and Fordham says he’s seen him wander into the kitchen at a restaurant to quiz the chefs. Andrea says he plans his meals, standing at his desk overlooking Hyde Park and down to the harbour, and orders the groceries online. “He comes home from work after a long day and I ask him what is for dinner… he makes a cracking paella, he makes the world’s best schnitzel, he’s a very good cook.”

Fordham’s assessment is that he’s been a “calm, measured, trusted and effective police commissioner”. John Hartigan says Fuller “gets out there in the faces of crooks… it’s an old-fashioned remedy but one that works”. Winning over such people makes the job of being police commissioner so much simpler. No government or commissioner wants a rabid tabloid media on its back about policing, and so managing perceptions of crime is often as important as managing crime itself.

But if one unsolved crime has dogged his commissionership it is the baffling disappearance seven years ago of the toddler William Tyrrell. Fuller’s blunt assessment is that one of the largest, most important and expensive police investigations ever undertaken in NSW has been bungled by police. For years, he now claims, the detectives who ran that investigation had been pursuing suspects who “clearly” had nothing to do with William’s disappearance. The current team, which he appointed, had inherited “a bit of a mess”. The former lead investigator, Gary Jubelin, bit back, saying that “as commissioner, Fuller is ultimately responsible for the investigation that has been running the whole time he was commissioner”.

Fuller counterpunches, saying the reason Jubelin was removed from the case was because he was facing charges for unlawfully recording conversations with a person of interest in the case. “To suggest that a commissioner is going to run the investigative strategies for the case is a bit ridiculous,” he says. “And no commissioner, no superintendent, is going to sign off on the illegal activity he [Jubelin] was ultimately convicted of.” But if Jubelin’s stewardship of this high-profile investigation was so incompetent, why was he left in charge? Why did it take years for anyone to notice?

Fuller doesn’t resile from anything he’s said about the case. “I’m not a shoot-from-the-hip guy,” he says. “Everything I do in my office I think about and I calculate the risks. If I think there is an opportunity to help solve a crime, and along the way I cop some criticism, I feel that is just my job.” He says he has every confidence police will get to the truth.

Assessing Mick Fuller’s whirlwind and multifaceted commissionership is devilishly difficult. Some would say his resistance to drug law reform is locking us into the mistakes of the past. Others will find his defence of police strip-searches of teenagers unforgivable. There are those who are convinced he became too close to government and business and that he crossed that ill-defined line. But when you weigh up the enormous challenges he faced – the Lindt Cafe siege, the bushfires, the pandemic, the restructure of the service – you’d be a mean-spirited observer not to err on the side of him having done a good job.

On our drive to the pub I’d asked Fuller what he thought his legacy would be – how would he be remembered? “I’m hoping to get out of this job with people being indifferent about me,” he said. “That’s my ambition.” By his own measure he’s failed miserably. Everyone in NSW, it seems, has an opinion about the state’s top cop.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout