Larrimah lamenting its long lost larrikin Paddy Moriarty

A year after he vanished, one question haunts the tiny outback town of Larrimah. Where the hell is Paddy?

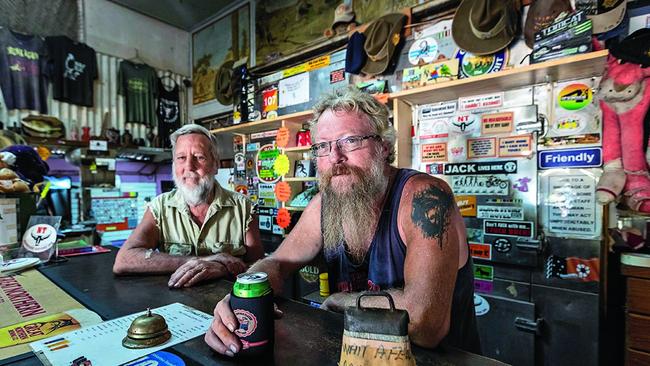

Boozy, thong-clad patrons sweating in their singlets spill out into the courtyard of the Larrimah Hotel. This place is more packed than it has been in years. A musician in a cowboy hat plays the Pink Panther theme tune on an electric guitar while a guy called Wingnut tries to get everyone to dance. He’s up against it. It’s around 42 degrees, almost everyone’s north of 60 and this isn’t quite a party. It’s a wake. A triple wake, really. Everyone is roasting, subdued, a little sad. And then something magic happens.

There are a few drops of rain on the tin roof, then a deluge, drowning out the music, sweeping in under the veranda, forming puddles around the entrance. The wet season downpour brings relief. It’s easier to laugh now it’s a little cooler. It’s Wingnut who notices the time. “Four-thirty,” he says, pointing at the clock. “Exactly when Paddy would’ve been going home for the day.”

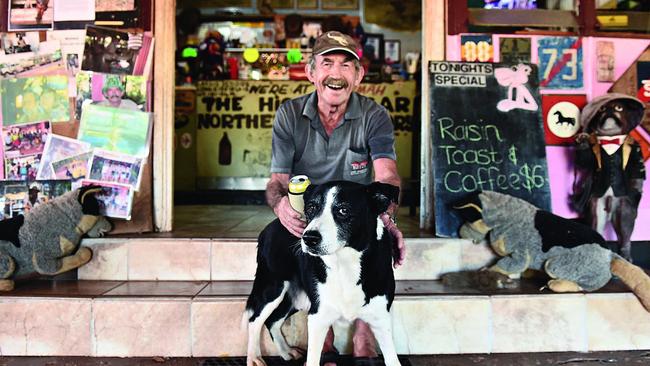

“He wouldn’t have left in this,” says Barry Sharpe, the publican, looking out at the downpour. “He would’ve been stuck here.”

Most days, a little extra time spinning yarns at the local with his mates wouldn’t have been a bad thing for Paddy. He loved this place. But his bar stool has been empty for almost a year now. People from all over the country used to drop in to see Paddy and hear some of his tall tales. Today, they’re here to remember him.

The case file reads like fiction. On Saturday, December 16, 2017, Paddy Moriarty, 70, and his kelpie-cross Kellie vanished from Larrimah, population 12, 180km south-east of Katherine in the Northern Territory. After consuming about 10 XXXX Golds, he left the Larrimah Hotel on his quadbike, Kellie aboard, around dusk and rode the 100-odd metres across the Stuart Highway to his modest home — an old service station complete with remnants of bowsers out the front, located metres from the main road. When he failed to turn up at the pub the following day, Sharpe went to Paddy’s house looking for him and found his friend’s hat, keys and bank card on the table, along with his dinner, ready to be heated up. But no sign of Paddy. At first he thought he might have gone to visit a mate, but on Tuesday, when Paddy still hadn’t turned up, Sharpe called the police.

By Thursday, hundreds of police officers, emergency service workers and volunteers were scouring the area, covering 80sq km by foot, motorbike and helicopter over three days, but they turned up nothing. It was as if Paddy and Kellie had walked out the back door and been swallowed up by the landscape.

Larrimah is a place with a backstory: the no-horse town, full of senior citizens, has had its share of run-ins. At one point there were two rival progress associations and no shortage of accusations: arson, theft, hooning. Paddy was embroiled in a bitter rivalry with a 75-year-old woman who, until now, was best known for her crocodile pies.

Police considered whether his disappearance might have been accidental — that he was killed by a snake, say, or fell down a sinkhole — and have all but ruled that out. They say he probably met with foul play and now, plenty of people are pointing the finger at their own neighbours.

“It’s a classic whodunnit mystery. Where the hell is Paddy?” says Detective Sergeant Matt Allen of the NT Police Crime Division. He and his team have been haunted by the case; nothing about it makes sense, and there’s no evidence to speak of. There’s also an added layer of responsibility because Paddy was born in Ireland and didn’t have any family in Australia. “It’s constantly on my mind,” Allen says.

It’s perhaps unsurprising there’s been so much interest in the story. A steady stream of local and international journalists have made the 500km trek down the Stuart Highway from Darwin to knock on doors and try to find out what happened. There’s been a podcast. Hollywood buzz. Documentary crews. Apparently, Paddy always wanted to be famous.

Karen Rayner, who used to work at the pub and knew Paddy for three years, knows that this isn’t what he meant — no one wants to be famous like this. But the media attention has its benefits, potentially advancing the police case and keeping his memory alive. “Paddy never expected anything from anyone, so he appreciated it when someone did something for him,” she says. “I think he would have appreciated that people care.”

Los Angeles-based producer Thomas Tancred was so caught up in the story that he flew out to Australia to start shooting footage in the hope of making a doco-series. “As soon as I read the articles and heard the podcast, I was hooked,” Tancred says. “I found myself up at night pondering what could have actually happened to Paddy.”

The town even looks like a film set. Maybe it’s the contrast of the red earth and the blazing sky, or the collection of heritage buildings made into homes. At the centre is the pub, a charming, haphazard structure painted bright pink so you don’t miss it driving past at 60km/h on the highway. Larrimah has been precariously close to extinction for years and Paddy’s disappearance is an open wound on its surface. “It’s sort of a sad place now. Quiet,” Sharpe says. “Everybody’s dumbfounded by it. He’s still thought of. There’s an empty seat around here that should be full.”

The twang of an old cowboy instrumental leaks out across the Never-Never. “Get your dancing thongs on!” cries musician Bernie Flynn as he strums. It’s the kind of tune that conjures an image of Paddy, his lush moustache and his good hat: the perfect backing track to his bottomless well of stories about his move from Ireland as a young man and his years working on cattle stations across the Northern Territory. Perfect for his Last Hurrah. “Ghost Rider was Paddy’s favourite song,” says Flynn when he takes a break, helping himself to a beer from the styrofoam Esky at the centre of the pub. He’s been playing gigs at the Larrimah Hotel for 15 years and Paddy would always front up and put in a few requests. “He liked old instrumentals and Irish jigs,” he says. “One night he made me play Guitar Boogie three times.”

Des Barritt pauses beside the pub’s photo board, packed with dozens of photos of Paddy — always smiling, always wearing a hat. There’s an Irish wreath laid under it. His friends had hoped to place his signature hat here too, but it’s still police evidence.

A year ago Barritt was among hundreds of emergency responders out searching for Paddy in 47-degree heat. “We tried our hardest to find him,” he says. “We searched on and off for a few weeks. Pretty soon most of us knew that something bad had happened.” Based 80km away in Mataranka, the former school principal was a friend of Paddy’s. “It’s hard [searching] when it’s someone you know but it gives you heart to get into it, because you’re desperate for an outcome.”

As the night rolls on, one by one, between Flynn’s songs, people sidle up to the microphone to pay brief tribute to their mate. There are friends from Hervey Bay, Darwin, Mataranka, Katherine and Tennant Creek — regulars who drink here, former pub workers, people who work on surrounding stations, travellers who stopped in years ago. Bill “Billy Lightcan” Hodgetts has wandered in from his permanent caravan out the back and Larrimah’s oldest resident, Lenny Hodson, 83, is cracking jokes on the veranda.

But there’s a palpable absence at this party: only half the town’s turned up. The rifts here run deep, even now.

Larrimah’s rarely busy but on June 7, 2018, the town was deserted. A coronial inquest had called almost every resident up the highway to Katherine to give evidence. It was less than six months after Paddy had disappeared, an unusually short period to have passed before an inquest, but time’s not on Larrimah’s side. The locals are getting on — nearly everyone’s in their 70s, a fact that adds a timer to the police investigation.

One by one the residents shuffled into the courtroom, all in their best attire, and were questioned in front of Coroner Greg Cavanagh. It was as if they were all speaking about a different person. Sharpe described Paddy as a “happy-go-lucky bloke” who welcomed everyone to the bar; Bobbi Roth, Sharpe’s neighbour who he hadn’t spoken to for more than a decade, said Paddy would “swear at me and throw abuse at me”. Her husband, Karl Roth, said Paddy had an “Irish temper” after a couple of beers; former Larrimah Hotel barman Richard Simpson said, “I don’t know anyone who’d ever wish Paddy any harm”.

Fran Hodgetts, Paddy’s nearest neighbour, owns the country’s most remote and curious Devonshire teahouse and is famous for her buffalo, camel and crocodile pies. She tells of a decade of bad blood between her and Paddy, claiming, among other things, that he’d stolen her umbrella, abused her customers, cut down her security cameras and chucked dead wallabies into her yard. In the year since Paddy’s disappearance Hodgetts has come under intense scrutiny from police, the media, other residents and passers-by. Running a business in a remote town comes with many challenges; now she has people driving past yelling “murderer” at her and putting up signs for “Sweeney Todd pies”.

“I never done anything to him,” she told the court. “I’m f..king riddled with arthritis, can you imagine me carrying a dog and a body?” Police have searched her property and found no evidence linked to Paddy’s disappearance. The weight of it all had taken a toll on Hodgetts and her business, she told the court. Her reclusive gardener, Owen Laurie — who most residents had never seen up close until his picture appeared in the paper after the inquest — said his heart condition had been exacerbated by the stress of being questioned over Paddy’s disappearance. He told the court he’d been drawn into the feuds between Fran and Paddy but also denied involvement. “I’ve got osteoarthritis,” he said. “If I did something violent like that, I’d break all my bones.”

The inquest was adjourned six months ago, with its findings yet to be handed down. But “the investigation is ongoing, detectives are still working on the matter,” says Detective Sergeant Allen. “We don’t just stop because time has passed, but we could still be having this conversation next year. Hopefully not.”

Garry “Wingnut” White is emotional. He wantsto give a speech for his friends Barry and Paddy, “two of the best blokes you’d ever meet”, but he’s worried he might cry. This isn’t just Paddy’s Last Hurrah, it’s Barry Sharpe’s too. After 15 years, the publican is retiring. He’s 76 and suffering from prostate cancer. After a few false starts, Wingnut takes the microphone. “If it wasn’t for Barry, this place would’ve been closed down years ago,” he says. “It was Barry who kept it going. I remember at the beginning, I helped paint the pub pink. Forty litres of pink paint — I got to hate pink by the end.”

There are a few laughs. Everyone’s been copping jokes about drinking in a pink pub for years. To call the place an icon is understating it. It’s a character in its own right — one of the town’s most important and eccentric. The historic building is surrounded by Pink Panther sculptures in various states of action and repose: riding a triple-tandem bike, flying a gyrocopter, reclining in a deck chair. Larrimah’s contribution to Australia’s obsession with oversized novelty architecture is a giant beer bottle, a legacy from when the pub sold the most two-litre Darwin Stubbies in the country.

It’s part pub, part hotel, part caravan park. It’s also the post office, general store and zoo, with three crocs, two emus, some wallabies, snakes, squirrel gliders and more than 500 birds. Or at least it was until recently. Most of them have been rehomed and now the cages are eerily quiet.

“I love this place,” Wingnut says. “I love Barry. Barry Sharpe, one of the Northern Territory legends. And you can say that. Best bloke I’ve ever met. He’s like a big brother to me. Paddy was also like a brother.”

With so much changing and leaving, it’s hard to know what to mourn. They’re not farewelling the pub, exactly. There’s a new owner and a sense of momentum about what might happen here. Talk of getting a fuel pump put in again over the road, fixing the place up, capitalising on the town’s history and tourism potential. But there’s also a sense that whatever happens, it won’t be the same.

So the night hovers between madcap and melancholy and in the lulls between songs, memories and tall tales spill out. “Remember that time the baby crocodile they used to keep in a fish tank on the bar bit a Chinese tourist?” someone says. “And that bloke who came in saying he was God — he wouldn’t leave.” There was the time another blow-in demanded to be airlifted out to have a tiny spider bite on his neck treated — Spiderman, they called him. And a ghost in a Model T in the carpark, and the parrot out the back that always yelled and swore at people.

The Esky is refilled; sausages are barbecued and eaten and cleared away. Everyone helps out with whatever needs doing — sweeping, making salads, moving around the kitchen and bar like they own it. They kind of do. Most people who’ve turned out for Paddy’s Last Hurrah worked here at some point, usually more than once, and not always on purpose. Suzi Geddes and her partner George McLean, a musician who died earlier this year, first came to Larrimah to play a single gig and ended up staying five months.

It’s a common story. Wingnut worked here five times, and Syd Bowden and his partner Alex Martin worked, drank and lived here. Karen and Mark Rayner stopped in to see Sharpe’s crocodile and have been here three years. There are plenty of others. People who dropped in for a drink and next thing they knew Sharpe had them behind the bar, serving. Weeks or months ticked by.

But none of them knows what they’ll find here next time they pass through. Fracking looks to be going ahead in the region and there’s talk the hotel could become a workers’ camp. In October, the nearby Wubalawun community won a battle for native title rights over one square kilometre in Larrimah; they’re keen to build the economy too.

There might be more nights when the car park’s overflowing if things go well for Larrimah. “It’s nice to see the place full again,” Suzi Geddes says. “It’s special. Unique. Full of history and people. The people who drop in, you get to know them and what they drink and it just feels like home.” She and her husband had even talked about buying the place, before he got too sick, so the evening is especially bittersweet for her. “It’s a changing of the guard,” she says. “The end of an era.”

Sharpe’s about the only one who’s not sentimental about it. “I don’t feel emotional,” he says. “I feel relieved.” He’s found a house to stay in just down the dirt road from the pub, where he intends to keep himself busy for as long as his illness allows. After two years weighed down by the pressure to sell the pub, he’s just glad to have found a buyer. “I hope it carries on and remains as it is,” he says. “But whatever happens, I’ve achieved something.”

It’s a strange thing, to have a send-off for someone who’s missing. Everyone agrees Paddy’s not coming back but there’s still no body. No conclusion. And no one’s been held accountable for whatever happened. There’s talk of another memorial, a real one. “This one’s just a practice run,” Sharpe says. They’ve got their eye on a patch of land over the road where they could put a plaque or a statue: a man and his dog, maybe, if they can get the permissions. It would be a place to go and pay their respects, or remember. Because what they can’t do is bring Paddy home. And even if they could, nothing here would be the same.

It’s getting late, and there’s less and less laughter. Someone refills the Esky again. When Bernie Flynn plays Desperado, no one says a word. There used to be a lot of parties here. Wild ones, where there’d be so many people camped on the veranda in swags that you couldn’t get to the bar, back when the rail was still running and the truckies all stopped in. But the town’s getting a bit long in the tooth for that. The pub’s getting old, too. It’s almost 70 — older, if you count the life it had before they shifted it to Larrimah. Tonight, its chequered history of shoot-outs and brawls and last-minute weddings seems like a distant echo.

At times, what happened to Paddy seems distant, too, like it’s another town’s story. “We can’t believe it actually happened here,” Karen Rayner says. “We can’t believe it happened to Paddy. People can have their opinion about Paddy, whatever they like. But we knew him for three years, and he was a great bloke.”

Paddy was the town raconteur, but in his absence everyone else tells his stories. Ronald Hill, a soft-spoken beekeeper from Mataranka who everyone calls Rusty or Rusty Bees, speaks up late in the evening. “I’d always look forward to coming down here,” he says. “Paddy would sit on one side of the pub, I’d sit opposite. I’d knock off with the bees at 4ish and we’d chat for a couple of hours. Every morning Paddy used to walk his dog around the dump and look for flowers. He’d ring me if he saw any, so I’d know for the bees. And he’d check on my water, in case a donkey knocked it over. I didn’t ask him to do that, he just did it. That was the kind of guy he was.”

Around 9.30pm Flynn puts down his guitar and announces a minute’s silence. Sharpe and Mark Rayner turn out the lights; someone unplugs the clattering fans. Everyone stares out at the empty scrub beyond the red dirt, their faces lit by coloured fiesta lights. It isn’t exactly silent: the air is thick with the sounds of insects and frogs, and the drinks fridge buzzes in the background. But there is enough quiet to remember the bloke who isn’t here, whose barstool is empty and whose absence haunts the place. The bloke who was the catalyst for all the other changes, all the eras that seem to be coming to an end. The bloke who’d never be quiet for a whole minute. Not Paddy. He’d have a story to tell you.

Kylie Stevenson and Caroline Graham’s Walkley Award-winning podcast, Lost in Larrimah, can be found here